plebeian - timg.co.il

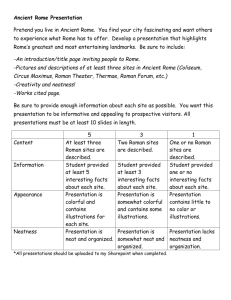

advertisement