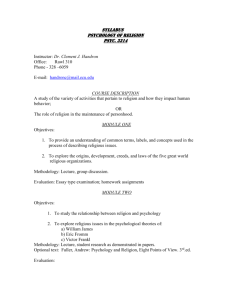

Culture Shock - Faculty Website Index

advertisement

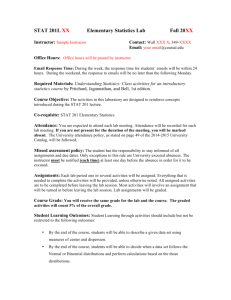

“Culture Shock!” Easing the Transition from High School to College Dr. Robinson Yost, Social Science Department Dr. Laura Yost, Distance Learning Department Table of Contents PPT Presentation High School versus College: Transitioning to Higher Education Selected Student Reflection Survey Results Reducing “Culture Shock” Samples Supplemental Source Material 1 High School versus College: Transitioning to Higher Education by Robinson Yost When a student is baffled by a college teacher, it is almost certainly because the teacher and the student are at cross-purposes. The student’s efforts are not matching the teacher’s expectations.1 Purpose: 1) Establishing as clearly as possible the expectations for student success in this course. 2) Examining some of the challenges in the transition from high school to college. Introduction: Depending on your previous academic experience (particularly in history classes), this course may have expectations & an approach differing from high school. For example, if the following student comments remind you of high school, then greater adjusting & adapting on your part are more likely: 1) Not a lot [of reading]. We hardly ever used the books unless in class. Maybe 2-3 pages a week of that. The tests were all multiple choice. We almost never had an essay, not even on finals. All I would do was re-read my notes and try to memorize everything. It only worked for a short amount of time. 2) My teachers were never enthusiastic and we watched a lot of war films. Less than 10 pages a week [of assigned reading]. We copied down a lot of notes…. We were given a study guide containing all that we needed to know. 3) My history classes consisted of doing packets. It would have been negative, because I didn’t retain any of the information. I would look up the information I needed to answer the question, then forget it all after the test. 4) In high school I usually got a list of people and events to memorize. Most of the classes involved the copying of notes from the overhead and left little time for discussion… I did not have many writing assignments. Usually we had worksheets to fill in with a couple short answer questions. 5) In high school I didn’t have any good experiences, because our history teacher was the boys basketball coach… The tests were multiple choice. I studied by the information given to us that told us what was going to be on the test. We didn’t do much writing at all… 6) My U.S. History class wasn’t very informative, because our teacher barely taught. She had her student teacher teach us the whole time… We were never assigned reading, they let us choose to do so.2 1 Robert Leamnson, Learning Your Way Through College (1995), p. 12. Student Surveys (Spring 2007). Students were asked to describe their experiences in high school history courses, how much writing they did, what types of tests and assignments, & how much read was assigned per week. 2 2 College students should NOT expect more of the same experiences especially like those described above. In fact, Kirkwood offers comprehensive assistance outside the classroom to aid students in transitioning to college-level work. College instructors will treat you as adults rather than children; as one experienced professor explains, this is not always an easy adjustment: Almost overnight, the rules change and we find that we can pick our own schedule, choose among teachers, skip class, miss the due dates, or sleep through the morning exam without anyone yelling at us or laying down the law. But neither will anyone spare us the consequences of those actions. Most of your teachers, following adult/adult rules, will assume that you are capable of handling your own affairs and would ask for advice of you needed it. It is sad to see a freshman misunderstand what is going on, make a shambles of the first year, and offer as explanation the perception that “no one here cares.” In such a case, adult behavior is being misinterpreted as lack of concern.3 Kirkwood instructors care about whether you learn & want you to succeed, but they expect each student to behave as an independent adult. Avoid excuses like “Nobody here cares” or “The teacher wants me to fail.” Your college success (or failure) is a CHOICE4—many people are readily available & willing to help you—but only you can make that choice. The four behaviors discussed in the next section all involve decisions that you can make. Each BAD CHOICE made by you increases the likelihood of poor performance, while each GOOD CHOICE enhances your chances of success. More importantly, each wise decision means that you will be a) getting more for your money, b) learning content knowledge & important skills, and c) earning an education rather than just working toward a slip of paper. Four Keys to Success: 1) Regular Attendance Even when there is no official “attendance policy,” it makes sense that coming to class matters and that missing classes lowers your grade.5 There is a correlation between grades and attendance, but what does attendance actually mean? It does NOT mean the ability to warm the seat of your chair; it means more than writing your name on a list during “roll call.” In college, attendance means being attentive (i.e., actively participating) and being prepared. As Robert Leamnson explains: “[Learning] is not an automatic consequence of attending and does not depend primarily on the teacher.” This may shock you, but it is a crucial part of transitioning to college life. Learning is something you DO TO YOURSELF, it cannot happen by passively sitting in a chair waiting for someone else to make you learn. With regard to lecturing: “The teacher is a 3 Robert Leamnson, Learning Your Way Through College (1995), p. 26 Based on a quote seen on a tee shirt at the Kirkwood Recreation Center (July 5, 2007): “SUCCESS IS A CHOICE,” Rick Pitino. 5 The Kirkwood Student Handbook (2007-2008) states: “Students are expected to attend all sessions of classes for which they are enrolled. Absences shall in no way lessen student responsibility for meeting the requirements of any class. Students are expected to know the attendance policy of each of their instructors. Failure to abide by an instructor’s attendance policy may result in failure.” p. 8 4 3 resource, a guide, and a coach… [The] lecture can be a highly efficient learning period, but not if you depend on the teacher to do all the work.”6 In college, attendance means being in class (on time), being prepared and paying attention. Merely sitting there does no more for your brain than staring at exercise equipment does to improve your physical fitness. Simply put, those who come to class and actively participate do better than those who do not. Attendance by itself, however, does not guarantee success. 2) Focused Reading Just as “attendance” can have differing meanings for incoming students and their teachers, so too can “reading” or “studying.” This is one of the most difficult areas of adjustment coming from high school to college. If the comments below sound familiar, then you will have more work to do: 1) Almost always the exams or test were multiple-choice and usually I did not study for them but right before the test to refresh my memory. 2) In high school, for history I really didn’t study for the test cause it was all common sense. Plus, it was way to [sic] easy on that test. 3) [Exams were] mostly multiple choice. I didn’t study, didn’t need to. 4) I crammed the night before. No essays. We had worksheets to match answers in the book with the questions. 5) I did study guides before the tests. These were all that would be on the test. I basically studied the study guide… My assignments were all study guides and multiple choice questions. 6) The tests were all multiple choice. The teacher gave us multiple-choice homework with the exact questions in different order. I did not do the homework and studied for the test by memorizing someone else’s homework just previous. 7) There were no essays and we got all answers to tests the day before…. We would look at notes that the teacher provided and fill out the study guide then study that for the exam…7 Notice above that “studying” or “doing the reading” is something that, if done at all, is only performed immediately before an exam. It usually involves “cramming” or shortterm memorization for short-term recognition; it can also include “study-guides” that tell you exactly what you need to know for tests. These “techniques” will not work in this class. Unfortunately, many students discover this the hard way, while others change their habits or seek out assistance. Here are several expectations regarding reading that may require changing your habits: Reading should be completed BEFORE CLASS begins, not during (it’s obviously inconsiderate and counterproductive to read your book once class begins). 6 Leamnson, 34. Student Surveys (Spring 2007). Students were asked to describe their experiences in high school history courses, how much writing they did, what types of tests and assignments, & how much reading was assigned per week. 7 4 Reading is not optional or supplemental to class lectures, it is a REQUIRED PART of the course (otherwise, why buy expensive textbooks?). Readings may have to be done MORE THAN ONCE (you may also need to look up words you don’t know in a dictionary or get assistance from the instructor). Productive reading should be done WITHOUT CONSTANT DISTRACTIONS (avoid the myth of “multi-tasking”; you cannot read productively while watching TV, talking on the phone, making an omelet, or driving your car). To summarize, students who regularly read for the bigger picture & meaning—free from distractions—will perform better than those who don’t. This takes discipline and practice, especially if you’ve never done it before, but it is a choice you can make. Finally, try reading like your teachers do: [Pretend] while reading, that you will have to present this material to someone else. Every teacher will tell you that nothing focuses the mind so keenly as the need to prepare a lecture. By pretending that you are going to teach someone else, you provide yourself with the motivation to focus your mind and get a clear idea of what the writer has to say… When you are doing assigned reading, try pretending that you are going to present a lecture to your classmates on this topic.8 3) Frequent Writing Just like regular attendance and focused reading, frequent writing will be a critical component of this course. There are many reasons why we will be doing a lot of writing, but the most important are that it offers opportunities to show what you’ve learned and how well you understand it. It also allows you to practice an essential skill that all college-educated people need and all employers want: the ability to communicate, clearly, concisely, and effectively. However, for writing to be useful, it “must be the kind of writing that actually activates the thinking part of the mind. Mechanically transcribing words from on page to another does not require that the words be thought about . . . That kind of writing [otherwise known as copying or plagiarism] does nothing permanent to the brain and does not cause learning. Writing causes learning when the words are firmly associated with thoughts or ideas.”9 For the entire semester you have an open invitation to discuss written assignments with me in person. If you struggle, then the ball is in your court to see me. You also have an open invitation to write practice essays outside of class (prior to our written exams) and hand it in to me for comments, suggestions, and a discussion on how to improve. This will take extra effort, but it’s worthwhile if you seek to improve. Writing will not improve unless you practice, get feedback, understand the feedback, and act on it accordingly. As Leamnson concludes: 8 9 Leamnson, p. 46. Ibid., p. 58. 5 Writing is an important element of learning, and writing well will require effort. However, being able to state, in clear and precise language, what you have come to understand brings great satisfaction. You will say some day that it was worth the effort… Writing provides another example of our central theme: Learning requires doing the difficult, but mere activities do not guarantee learning just because they are difficult. Learning comes from doing the right things. It seems a waste to spend time and energy writing and not to learn while doing it. Writing is hard work either way; why not engage the mind and learn as you go?10 Writing cannot be made easy, but the effort is worth it. Notice that effort is the key, but it is the right kind of effort. Just as with exercise, you may not see results immediately, but the long-term benefits will pay off in the end. 4) Asking Questions At the risk of beating a dead horse: ask questions and avoid making excuses for why you couldn’t or didn’t. Those who ask for help demonstrate the mature attitude that they want to learn; while those who wait until it is too late are desperate only for a grade. Two strengths of Kirkwood are its small classes and numerous opportunities for personal interaction with staff & instructors. In this class, there are many opportunities to ask questions: In class (simple, straightforward, raise your hand and ask) By phone (see office phone number in syllabus) By e-mail (see syllabus) Outside of class (see office hours in syllabus) In writing (you have an open invitation all semester long to write questions on a sheet of paper and hand them at the end of class) In short, avoid reasons why you could not or would not get help—it’s up to you to take the initiative and make wise choices. Again, Leamnson explains a common misconception common among new students: The absence of continual supervision and monitoring by teachers is, I believe, the aspect of adult behavior that most confuses new students. Teachers who do not advise students that they have missed assignments or quizzes, or that their performance is not up to par, are seen by some students as indifferent or unconcerned. Quite simply, this is not a valid conclusion.11 Teachers at Kirkwood want you to become better thinkers & learners, but they also will assist you by treating you like adults. Take the first steps: get help, ask questions, and you will get more for your money. After all, you’re here to get what you’re paying for: an education. 10 11 Leamnson, pp. 67-68. Ibid., p. 27. 6 Conclusion: Everyone is naturally anxious to start something new, but if you take this advice to heart it will make a difference to your success in this course (and your overall success in college). If you doubt this, consider this sampling of student comments when asked what they would keep about course(s) and the most important thing they learned: 1) When you have quizzes all the time the students have to do the work and get an actual education out of it. [Fall ‘04, Europe: Age of Revolution] 2) Basically my study habits. I knew for this class I had to take the time to sit down, not only to read, but comprehend & take notes over the text. [Fall ’04, Ancient Mediterranean World] 3) Learning is up to the individual, you have to put in the work to get out the knowledge. [Spring ‘05, Europe: Age of Monarchy] 4) You must force yourself to have discipline when learning. You can’t memorize facts, you must interpret what they mean. [Spring ’05, History of Science] 5) The work ethic it caused me to develop to do well in this class. I’d keep it because it is an important skill not only in college classes, but an important life skill to keep. [Fall ’05, Ancient Mediterranean World] 6) I would keep the demands you place on students. It helps keep students focused and involved. [Fall ’05, Europe: Age of Revolution] 7) Sometimes large tasks seem extremely daunting and it is hard for me to get motivated to do them, but through this class I learned how gratifying it is to complete them. [Spring ’06, Europe: Age of Nationalism] 8) How to read, take notes, & analyze all at the same time. I’ve always been able to slide by in my classes & never have to open the textbook. This is really the first textbook I’ve truly had to read. [Spring ’06, Europe: Age of Monarchy] 9) Probably the study habits, in this class we’ve been required to read all the material prior to class and take notes. I’ve never been forced to do that, and that is why I struggled early on. This class has prepared me to do what is necessary in the future [Fall ’06, Ancient Mediterranean World] 10) The reading I feel was necessary to survive the course. It actually imprinted the knowledge in my head instead of going in one ear and out the other. [Fall ’06, Ancient Mediterranean World] 11) Doing the work myself, and not expecting the teaching to tell us everything that is on the test. Making my note taking technique better [Spring ’07, Holocaust & Genocide] 12) How to learn. I am a high school senior and this class really helped prepare me for college level work. [Fall ’07, Ancient Mediterranean World] QUESTIONS: 1) What specific things will be the most difficult for you to adjust to? Why? 2) What does college education mean to you? Do you expect it to be different from high school? If so, then how specifically? Be specific. 7 COURSE INTRODUCTION HANDOUT: Articulate Expectations ASAP! KTS Understanding Cultures: Latin America (UCLA) Spring 2008 Dr. Laura Yost Course Expectation & Requirement Highlights P lease review the items listed below – they are to help ensure that our semester runs smoothly! They are being provided by the instructor so that you can have a better understanding of what key issues have caused some problems in the past – and in by calling them to your attention, they can be avoided in the future . . . On Behalf of the Students Routinely & regularly attending class meetings Routinely & regularly having access to an Internet-connected computer Familiarizing yourself with CE6 usage & the KTS UCLA online format When necessary, utilizing Kirkwood-provided CE6 support services, such as: http://www.kirkwood.edu/elearning - where tutorials, demos, and other tools are available for CE6 users Being able & willing to access Video on Demand (VOD) capabilities (only accessible via Kirkwood sites) to review classes, watch documentaries, learn supplemental information, etc. Knowing course policies & procedures, syllabus material, and other information regarding class format & function as provided by the instructor and/or the college Consistently checking CE6 or other regularly-used e-mail services (especially after contacting instructor) Informing instructor immediately when encountering technical issues or complications & actively working to correct those Ensuring attached documents are attached & proper content is provided when submitting work Including your NAME & SITE LOCATION on ALL WORK – this ensures you will be awarded the points you have earned! Providing paperwork in cases of excused absences (obituary notices, doctor- or supervisor-provided notes, etc.) Completing excused make-up work within the time provided by the instructor 8 On Behalf of the Instructor Routinely & regularly attending class meetings Routinely & regularly having access to an Internet-connected computer Holding office hours or announcing/posting when cancelled & then scheduling make-up meeting times Checking e-mail regularly & responding as quickly as possible (ideally within a 48hour period; if you have NOT heard from me by that point, assume that e-mail did not go through & please resend it) Contacting students if uploaded, e-mailed, or otherwise submitted content does not go through (for example, an attachment cannot be opened) – unfortunately, this cannot be a routine occurrence on behalf of individual students Announcing assignments, as well as any scheduling changes, in conjunction with CE6 posting = never just stating changes via the website alone Posting assignments in a timely manner via CE6 Encouraging in-class participation & providing time at the end of each session – or the beginning of the following – for student questions 9 COURSE SYLLABUS: Follow-up With Paperwork Understanding Cultures: Modern Japan – Web-Blended (UCMJ:WB) Section #: CLS-165-CRTZ3 Meeting Time: Monday 7:00 p.m. – 9:50 p.m. Main Campus Room: Linn Hall 203A Origination Sites: As Assigned Communication Policies E-mail (through standard account): lyost@kirkwood.edu. Due to the increasing amount of junk e-mails and heightened risk of viruses, all e-mails MUST be written in the following format (UCMJ: whatever you need). Example - UCMJ: Help, UCMJ: Question, UCMJ: Student Concern, UCMJ: John Smith. (Accounts not accessed evenings and weekends.) Attachments: The flexibility of CE6 allows students to type material directly into the submission page as well as submit projects as attachments. If a student submits work through an attachment, and the attachment does not take, the instructor will follow up with an e-mail. The student will then have 24-hours to respond with the homework in question or it will be counted late. Course Materials Course Text: Pyle, Kenneth, The Making of Modern Japan, D.C. Heath & Company, Thompson Wadsworth, 1996. CE6: All students will log-in and work via CE6; please be sure you can access and navigate it. For assistance with any aspect of CE6 usage please contact the Distance Learning office – 214 Linn Hall, Main Campus – or visit the KCC Distance Learning website - www.kirkwood.edu/distancelearning. All out-of-class homework assignments will be provided via CE6 All out-of-class homework assignments will be submittd via CE6 All homework, exam, and reading assignment due dates will be posted via CE6 At times students will be asked to print out material for use in class (the instructor will announce this in class, as well as post the information online) At times students will be asked to submit their responses to some in-class assignments via CE6 10 Student Evaluation: Assignments, Assessments, Group Work General Homework Guidelines: Simply attending class and handing in homework is not enough. Students must follow directions, provide complete and thorough answers, display effort, contribute to group work, and participate in discussions to receive passing grades Homework (in addition to text reading assignments) will come from the course website or will be handed out by the instructor LATE ASSIGNMENTS are allowed; 2 points will be deducted from a student’s final score for each week an assignment is late LATE EXAMS are allowed; 10 points will be deducted from a student’s final score for each week an exam is late Assignments that refer to statements made in another source, regardless of type, need to be accurately cited (in most cases, indicating that the statement is quoted, is sufficient) Written assignments need to demonstrate that a student has read the material. Thus, to receive full credit he/she must be sure to include supporting details or evidence from the reading ONE or TWO sentence answers will NOT receive full credit, and in most cases will receive no higher than a C-range grade (please approach instructor with ANY questions you have) Be sure to answer a question sufficiently – simply stating “yes” or “no” is not enough Please be sure to approach the instructor with any questions you have about the material (confusing statements, unfamiliar vocabulary, etc.). Writing in assignments that you did not understand the material, were confused, or did not understand a question is not acceptable The instructor is here to help you – so please stop by or e-mail any questions that you have In addition to being announced in class, homework assignments will be posted via CE6 In-Class Writing Assignments: In-class writing assignments will be given based upon material presented in class through handouts, videos, movie clips, assigned readings, quizzes, etc. These may or may not be announced, and they may or may not be graded Their purpose is to gauge a student’s progress The assignments develop a student’s ability to make arguments based on interpreting facts and context STUDENTS CANNOT MAKE UP MISSED IN-CLASS WRITING ASSIGNMENTS STUDENTS CANNOT HAND IN IN-CLASS ASSIGNMENTS OUTSIDE OF CLASS Students cannot watch/make-up films on their own time & hand in their work (this applies to rentals or borrowing from the instructor); in the past the instructor allowed students to make-up films in the library but DVDs were NOT returned so this policy was discontinued 11 Plagiarism Policy According to Webster, to plagiarize is "to steal or pass off the ideas or words of another as one's own . . . to use created productions without crediting the source . . . to commit literary theft . . . to present as new and original an idea or product derived from an existing source." Kirkwood students are responsible for authenticating any assignment submitted to an instructor. If asked, you must be able to produce proof that the assignment you submit is actually your own work. Therefore, we recommend that you engage in a verifiable working process on assignments. Keep copies of all drafts of your work, making photocopies of research materials, write summaries of research materials, hang onto Writing Center receipts, keep logs or journals of your work on assignments and papers, learn to save drafts or versions of assignments under individual file names on computer or diskette, etc. The inability to authenticate your work, should an instructor request it, is sufficient grounds for failing the assignment. In addition to requiring a student to authenticate his/her work, Kirkwood Community College instructors may employ various other means of ascertaining authenticity - such as engaging in Internet searches, creating quizzes based on student work, requiring students to explain their work and/or process orally, etc. Course Plagiarism/Cheating Policy (Supplemental) Students are allowed to discuss work assigned for individual completion. Work must be in a student’s OWN words, unless cited properly. However, students are NOT allowed to turn in work that is the same, copied from another student’s, or highly similar (with some words changed, sentences rearranged, etc.). ALL forms of this type of work are considered cheating and will receive a ZERO; they cannot be made up. 12 SUPPLEMENTAL SOURCE MATERIAL The Modern Practice of Adult Education: From Pedagogy to Andragogy Malcom Knowles “ . . . it is no longer functional to define education as a process of transmitting what is known; it must now be defied as a lifelong process of continuing inquiry. And so the most important learning skill of all – for both children and adults – is learn how to learn . . .” “The problem is that education is not yet perceived as a lifelong process, so that we are still taught in our youth only what we ought to know then and not how to keep finding out. One mission of the adult education, then, can be stated positively as helping individuals to develop the attitude that learning is a lifelong process and to acquire the skills of self-directed learning. In this sense, one of the tests . . . is the extent to which the participants leave a given experience with heightened curiosity and with increased ability to carry on their own learning.” “Another ultimate need of individuals is to achieve complete self-identity through the development of their full potentialities. Increasing evidence is appearing in the psychological literature that complete self-development is a universal human need . . .” “The idea of maturity as a goal of education must be defined more specifically . . . if it is to serve as a guide to continuous learning.” SELECTED DIMENSIONS OF ACADEMIC MATURITY From dependence to autonomy. “One of the central quest of [students’] lives is for increasing self-direction. . . . The fact is that every experience we have in life tends to affect our movement from dependence toward autonomy. From passivity toward activity. “And the way they are taught to participate in school and in other educative experiences – whether they are put in the role of passive recipients of knowledge or in that of active inquirers after knowledge – will greatly affect the direction and speed of their movement in the direction of growth.” From small abilities toward large abilities. “There is a tendency in human nature, once we have learned to do something well, to take pride in that ability and to rest on the laurels it wins us. Since each newly developed ability tends to be learned in its simplest form, this tendency can result in individuals becoming frozen into the lowest level of their potential performance. A skillful facilitator of learning helps each individual to glimpse higher possible levels of performance and to develop continually larger abilities.” From few responsibilities toward many responsibilities. 13 From narrow interests toward broad interests. “Anything that causes an individual’s field of interests to become fixated within a particular circle or to recede to small circles is interfering with an important dimension of maturation.” From focus on particulars toward focus on principles. “To a child’s mind each object is unique and each event is unconnected with any other. The discovery of principles enabling a person to group objects and connect events is the essence of the process of inquiry. One of the tragic aspects of traditional pedagogy is that it has so often imposed principles on inquiring minds and has therefore denied them the opportunity to mature in the ability to discover principles.” From the need for certainty toward tolerance for ambiguity. “The basic insecurity of the child’s world imposes a deep need for certainty. Only as our experiences in life provide us with an increasing sense of security and selfconfidence will we be able to move in the direction of a mature tolerance for ambiguity – a prerequisite for survival in a world of ambiguity.” From impulsiveness toward rationality. “True maturing toward rationality requires self-understanding and self-control of one’s impulses.” Self-Directed Learning: A Guide for Learners and Teachers www.tobincls.com/responsibility.htm (partial excerpt) Malcom Knowles “The simple truth is that we are entering into a strange new world in which rapid change will be the only stable characteristic. And this simple truth has several radical implications for education and learning. For one thing, this implies that it is no longer realistic to define the purpose of education as transmitting what is known. . . . Thus, the main purpose of education must now be to develop the skills of inquiry. When a person leaves schooling he or she must not only have a foundation of knowledge acquired in the course of learning to inquire but, more importantly, also have the ability to go on acquiring new knowledge easily and skillfully the rest of his or her life. A second implication sis that there must be a somewhat different way of thinking about learning. . . . We must learn from everything we do; we must exploit every experiences as a ‘learning experience.’ . . . Learning means making use of every resource – in or out of educational institutions – for our personal growth and development. A third implication is that it is no longer appropriate to equate education with youth. . . . Education – or, even better, learning – must now be defined as a lifelong process. The primary learning during youth will be the skills of inquiry and the learning during you will be the skills of inquiry and the learning after schooling is done will be focused on acquiring the knowledge, skills, understanding, attitude, and values required for living adequately in a rapidly changing world. To sum up: the ‘why’ of self-directed learning is survival- your own survival as an individual, and also the survival of the human race. Clearly we are not talking here about something that would be nice or desirable; neither is we talking about some new 14 educational fad. We are talking about a basic human competence-the ability to learn on one’s own-that has suddenly become a prerequisite for living is this new world.” “ . . .’self-directed learning’ describes a process in which individuals take the initiative, with or thought the help of others, in diagnosing their learning needs, formulating learning goals, identifying human and material resources for learning, choosing and implementing appropriate learning strategies, and evaluating learning outcomes.” “ . . . self-directed learning usually takes place in association with various kinds of helpers, such as teachers, tutors, mentors, resource people, and peers.” REFERENCED AND SELECTED REFERENCES Ronald J. Areglado, R.C. Bradley, & Pamela S. Lane, Learning for Life: Creating Classrooms for Self-Directed Learning William J. Rothwell & Kevin J. Sensenig (editors), The Sourcebook for Self-Directed Learning Daniel R. Tobin, All Learning Is Self-Directed Malcolm S. Knowles, Self-Directed Learning: A Guide for Learners and Teachers Malcom S. Knowles, The Modern Practice of Adult Education: From Pedagogy to Andragogy Self-Directed Learning (SDL) http://www.selfdirectedlearning.com/ while oriented towards primary education, has a strong self-assessment section Techniques, Tools, and Resources for the Self-Directed Learner http://home.twcny.rr.com/hiemstra/sdltools.html learning contracts, self diagnostic forms, readiness scales, self assessments, etc. University of Medicine & Dentistry of New Jersey: Center for Teaching Excellence http://cte.umdnj.edu/active_learning/active_sdl.cfm general collection of articles & publications providing an introduction to Self-Directed Learning as well as “Methods & Tools” 15 Free Management Library http://www.managementhelp.org/trng_dev/methods/slf_drct.htm primary article on developing SDL in the workplace, with handful of supplemental, background, web links http://www-distance.syr.edu/sdlhome.html general SDL information Consortium for Research on Emotional Intelligence in Organizations: Rutgers http://www.eiconsortium.org/research/self-directed_learning.htm “Unleashing the Power of Self-Directed Learning,” Richard E. Boyatzis (PDF version) from “Changing the Way We Manage Change” 16