Activity-Based Costing: a Case Study on a Taiwanese Hot Spring

advertisement

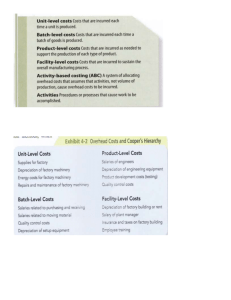

Activity-Based Costing: a Case Study on a Taiwanese Hot Spring Country Inn’s Cost Calculations Wen-Hsien Tsai Department of Business Administration National Central University, Chung-Li, Taiwan, ROC Jui-Ling Hsu Department of Business Administration National Central University, Chung-Li, Taiwan, ROC Department of International Trade Ta-Hwa Institute of Technology, Hsin-Chu, Taiwan, ROC Abstract The aim of this paper is to analyze the operational costs of a hot spring inn in the Yang-Ming-Shan area of Taiwan. The activity-based costing method was used to compute lodging, hot spring use and meal serving costs per customer. This paper overcomes all the obstacles to implementing full-scale ABC-based accounting to this hot spring country inn. In this case, products, defined as hot spring use, lodging and meal serving are used as the cost objects. We define five activity centers: the cleaning activity center, the customer service center, the cooking and foodservice center, the reception service center and the management center. Finally, we use the ABC method to calculate the costs of hot spring use, lodging and meal serving as NT$ 31.64, NT$ 306.21 and NT$ 67.28 per customer respectively in the busy winter seasons. The paper also compares the ABC method with the traditional costing method and concludes that the ABC method is practical and appropriate for such a hot spring country inn and yields more accurate information for cost management and pricing decisions. Key Words: Activity-Based costing, Country Inn, Hot Spring, Cost Analysis 1. Introduction Researchers in management accounting have traditionally been, above all, interested in the accounting systems of large manufacturing companies. Most accounting researchers interested in service production have conducted their research in non-profit seeking, public-sector organizations (Pellinen 2003, p. 217). Outside the non-profit sector, the number of studies on the management accounting practices of service organizations (profit seeking) have remained very limited (Brignall et al., 1991; Sharma, 2002). More unfortunately, non-traditional lodging, (i.e. the B&B industry), is totally lacking in management accounting research, in contrast with the traditional lodging industry, which is quite well-researched. The aim of this paper is to illustrate how activity-based costing (ABC) can be applied to a hot spring country inn in order to obtain information on activities and products for decision making purposes. ABC is a cost-accounting method that allocates resource costs to products using a two stage procedure on the basis of activity consumption by drivers. It’s a method which can overcome many of the limitations of traditional cost systems which can distort product cost because they allocate the overhead costs to products mainly by direct labor hours (or volume-related measures). This is particularly prone to result in distortions in cases where there is a large overhead ratio or a high degree of product diversity. The country inn style of non-traditional lodging, especially suitable for ABC application, has various products such as lodging, hot spring use and dining which belong to different market segments. The indirect costs of this inn constitute an important proportion of the total costs (53.46%). In such a typical situation, the valuing of products of this inn may be distorted by a traditional accounting system. This article portrays an attempt to apply the ABC model to a hot spring country inn where the managers normally use a traditional accounting method to acquire product cost information. Our case study is presented in the hope of contributing to management accounting research in the non-traditional accommodations area. In addition to the introduction, there are four main sections in this paper. The subsequent section reviews previous research in management accounting for the lodging industry. The third section presents the ABC model. The fourth section illustrates the implementation of ABC in a specific case. The fifth section compares results of the ABC method and the traditional method. Some conclusions are presented in section six. 2. Literature review Poorani and Smith (1995, p. 58, 63) observe: “The hotel and the B&B industry have very different financial aspects arising from contrasting ownership motives. In the hotel industry the emphasis is on maximizing profitability whereas the B&B industry has been traditionally characterized by innkeepers who embarked on inn-keeping as a second career to satisfy lifestyle goals. But the current economic environment has blurred that distinction. Hoteliers are trying to be more sensitive to customers’ needs and create an environment for personalized service. Meanwhile, many entrepreneurs are entering the B&B segment with strictly financial motives”. Their investigations attribute financial characteristics to the B&B industry and find that innkeepers in USA with midsize and larger operations not only were highly successful in reaching their career goals but also achieved their economic objectives as measured by return on investment and equity. However, notwithstanding the importance of financial aspects, the studies in cost structure of the B&B industry anywhere in the world were rare. One reason is the inn’s private-ownership arrangements; others are the fragmented industry structure and the lack of systematic cost and revenue data. Unlike the situation in the B&B industry, there have been a large number of studies in the hotel industry. In the management accounting side of the tourism industry, research has been conducted both in tourism management research and in accounting research. Studies have been carried out in passenger transportation (Dent, 1991; Rouse et al., 2002), restaurants (Ahrens and Chapman, 2002), and hotels (Downie, 1997; Edgar, 1998; Noone and Griffin, 1999; Mia and Patiar, 2001; Pellinen, 2003). Downie (1997, p310) emphases the importance of considering how accounting information can be analyzed to support marketing decisions more effectively. Noone and Griffin (1999, p111-128) designed a customer profitability analysis (CPA) integrating activity-based costing (ABC) and customer segments in order to find profit yield in a hotel. Mia and Patiar, (2001, p111) interviewed only 35 managers and indicated that general managers and department managers took equal account of the management accounting system, but general managers were more content with the accounting system and valued financial information more than department managers. Pellinen (2003, p217) studied the pricing decisions in six tourism enterprises (including a hotel) and suggested the enterprises observed all took their prices from the leading company. Thus, the importance of cost accounting is limited with reference to pricing decisions from the managerial viewpoint. Obviously, most of the studies have focused on hotels. As Harris and Brown (1998, p161) pointed out, hotels, which typically comprise food, beverage and lodging, can be used to illustrate that the context of the hospitality product can provide a complete range of characteristics in a single arena. Actually, the B&B industry also has all those characteristics. But this segment, specifically nontraditional lodging (including B&B inns, country inns, small hotels, condominiums, and vacation homes), has remained an enigma to industry analysts and researchers. Lanier et al. (2000, p91) think this is in part because the analysts and researchers willfully overlook it in favor of the traditional lodging industry, pleading lack of data (Statistics dealing with properties of fewer than 20 rooms are usually estimated or based on small samples. Since most country inns do not reach the 20-room threshold, statistics for these properties have not been collected regularly, unlike other industry segments). This is so prevalent in studying management accounting in the accommodation industry and that there is a huge lag for researchers to make up for. Summarizing the above, previous studies on accounting and product costing, pricing of hotels propose that : (1) the knowledge in accounting is essential in hotel management, (2) the connection between accounting information and marketing is important, and (3) activity-based costing, cost-volume-profit analysis, yield management, and segment profit analysis were among the most relevant management accounting methods, (4) the lack of management accounting research in non-traditional lodging industry needs to be made up. 3. Activity-based costing Cooper and Kaplan (1988) have developed what they believe is a better alternative to the traditional cost calculation model. They argue that as products differ in the complex process of manufacture, they consume activities in different proportions. The activity-based costing method (ABC) promoted by Cooper and Kaplan provides a more accurate measure of cost because it traces indirect costs more closely with regard to the different types of activities consumed. Armed with knowledge of what activities are consumed by each product and the resource cost of each activity, one can budget costs for a diversity of products. However, the traditional accounting method usually assigns overhead costs of products by using volume-related allocation bases such as labor hours, direct labor costs, direct material costs, machine hours, etc. This will not critically distort the product costs as the overheads are just a small portion of the production process. But in situation where there is a large diversity of products, or where there is a high level of automation, as Brimson (1991, p. 179) pointed out, the overheads’ distortion will be significant. In our case, for example, high-volume products (hot spring use) may consume more direct labor hours than low-volume products (meal serving), but do not necessarily consume more purchasing activity costs. The ABC model applied to the case of this hot spring country inn is depicted in figure 1. The ABC systems focus on the accurate cost assignment of overheads to products. In the cost assignment view, the assignment of costs through ABC occurs in two stages: cost objects (i.e., products or services) consume activities, activities consume resource costs. In practice, this means that resource costs are assigned to various activity centers by using resource drivers in the first stage. An activity center is composed of a group of related activities, usually defined by function or process. The group of resource drivers is the factor chosen to estimate the consumption of resources by the activities in the activity centers. Every type of resource assigned to an activity center becomes a cost element in an activity cost pool. And, in the second stage, each activity cost is distributed to cost objects by using Figure 1 ABC Model in a Hot Spring Country Inn Cost of Resources Indirect Cost First Stage Resource Drivers Activity Center Cleaning Customer Reception Cooking Management Center Second Stage Activity Drivers Cost Objects Cost of Lodging Cost Objects Cost of Hot Spring Cost of Meal Use Serving a suitable activity driver to measure the consumption of activities by products or services (Turney, 1992). Then, the total cost can be calculated by adding the various activities costs to a specific product or service. And the total cost divided by the quantity of the product can acquire the unit cost of product. In our case, the inn provides three products, lodging, hot spring use and meal serving. We define five activity centers, namely the cleaning center, the customer service center, the reception center, the cooking and foodservice center and the management center. Each activity center is composed of related activities, clustered by their function. As Harris and Brown (1998, p161-162) indicated, a hotel operation can be used as an example of hospitality products, in the same way the elements of a hot spring country inn of the B&B industry also can be used to illustrate non traditional accommodation products. For instance, the provision of rooms constitutes a nearly ‘pure service’ product incorporating a large proportion of service elements. It can be defined as the rental of a certain amount of space for a specified period of time and is thus an intangible good containing a high level of service provision. The provision of hot spring use also represents a service product: it includes hot spring rental and service activities. Furthermore, the meal serving provision, comprised of purchasing, distribution and conversion of food into meals, again constitutes a service product. The main advantage of ABC lies in that it provides a more accurate and real cost computation, especially in situations in which product diversity is important and in which the indirect costs, not directly traceable to the products, represent an important proportion of the total costs. In addition, ABC also allows a deeper level analysis of product costs by explaining the relationship between products and activities. The improved accuracy of perception of the cost structure of products and the continuous process improvements in the various departments of an enterprise provide the substance of activity-based management (i.e. using ABC to improve a business). Studies of the implementation of ABC exist in various fields, e.g. of universities (Cropper and Cook, 2000), a hotel (Noone and Griffin, 1999), library service (Ellis-Newman and Robinson, 1998), distribution logistics (Pirttilä and Hautaniemi, 1995; Themido et al. 2000), (all of which belong to the service sector); of a manufacturing company (Spedding and Sun, 1999), an assembly line (Gunasekaran and Singh, 1999), (which belong to the manufacturing sector); of a wholesale fish market (Lee and Kao, 2001), (agricultural sector); and of a radiotherapy unit (Lievens et al., 2003), (medical sector). All of them agree that ABC is a useful accounting model and able to obtain more accurate information about the cost structure as long as implementing managers choose the right drivers and define activities well. However, it is generally accepted that there is no universally appropriate accounting system suitable to all organizations in all circumstances (Emmanuel et al., 1990). But as Harris and Brown (1998, p162) point out, management accounting needs to be carried out in the context of the hospitality product in order to supply the necessary information for decision-makers if researchers expect to make a significant contribution to the industry. 4. A Case Study of a Hot Spring Country Inn The Professional Association of Innkeepers International defines that a country inn is a business offering overnight lodging and meals where the owner is actively involved in daily operations, often living on site. The hot spring country inn in our study is located on the Yang-Ming-Shan in the north of Taipei where it faces a very competitive hot spring tour market environment. It includes 6 twin rooms, 9 quad rooms, a hot spring pool for men (7109.2 square feet), another hot spring pool for women (3554.6 square feet) and 9 private hot springs bathrooms, covering a total area of 1 acre and 31076.45 square feet. This inn hires 25 full time employees and 13 part time employees, and the owner who also lives there Table 1 Monthly Costs of Resources Resource life time Replacement value - Capital costs - Cost per month Rent-a-land 30 Owner’s lands 30 150,000,000 13,324,092 1,110,341 Buildings 30 16,050,000 1,425,672 118,806 Personnel Number Total Costs 700,000 Cost per month Full time staffs 23 9,060,000 755,000 Part-time staffs 13 2,448,000 204,000 Managers 2 1,320,000 110,000 is the general manager. Meanwhile, the inn faces very serious seasonal customer fluctuations. The average volume of customers for hot spring use can come to a maximum of 58,048 persons monthly in the winter season and a reaches minimum of 18,311 persons in the summer season. In addition, this hot spring country inn bears a heavy space and land costs due to the high cost of buildings and land in Taipei. The monthly costs of rent, lands, buildings and labor are showed in table 1. This inn doesn’t use any activity-based costing method in its accounting system except for the traditional one. Since activity-based costing can be very complex and time consuming, and even less in tourism industry, it is not widely applied in the manufacturing industries in Taiwan (Chen, 2001, p. 52). It is recognized that partial activity-based costing can be used to enhance rather than totally replace the accounting system when the company finds it too difficult to implement full-scale ABC-based accounting. Some companies also complain that the cost of ABC’s administrative and technical complexity, and of continuously generating activity data, exceeds any benefits subsequently derived from it, so that they reject proposals to implement ABC to their companies. Nevertheless, many firms still find they have success in cost reduction, product pricing, customer profitability analysis and output decisions when they adopt ABC (Chenhall and Langfield-Smith, 1998; Clarke et al., 1999; Innes and Sinclair, 2000; Cotton et al., 2003). Our traditional accounting cost information was gathered from 1 November, 2003 to 30 December, 2003. The figures for customers’ volume were acquired from the mean of the number of customers in these two months. In order to obtain a more accurate picture of Table 2 Activities Analysis and Assigning Activity to Product Using Activity Drivers (1) Resource (2) (3) Labor Material Activity & Utility l Cleaning 99,572 Changing 1,455 607 Washing 32,225 22,196 Clear up 91,475 (4) Total Cost (5) (6) (7) Quantities of Drivers Lodging Spring 20,155 119,727 Total (8) 5,454 Dining quantity activity driver Lodging Hot-Spring 3,749 410.2 6810.6 17.58/hr 2,062 960 0 0 960 2.15/hr 54,421 830 1,832 188.6 2,851 19.09/hr 21,623 113,098 0 0 10,710 Ordering 54,451 Carrying 75,220 Re-supply 4,320 Cooking 297,968 Purchasing 73,886 Check in 263,806 1,994 2,754 2,437 7,730 56,445 77,974 6,757 58,945 356,913 605 74,491 90,647 354,453 450 0 0 20 0 18.5 0 11,203 0 103,754 436 0 24 232.47 1,891.6 /out Admini- 0 0 4 2,010 198 10,710 10.56/number 450 17.17/number 11,203 5.04/number 103,754 0.75/number 460 2,010 14.69/hr 177.57/hr 240.5 309.73/hr 692.5 2,816.64 125.84/hr 7 779.2 102 1,091.2 34.51/space 6,336 1,440 56,750 33,240 91,430 0.07/person 27,156 1,440 56,750 33,240 91,430 0.297/person 36,608 1,049 37,657 Marketing 6,160 176 Accounting 26,400 756 210 strative Renting 700,000 Depreciation 1,229,147 251.96 1,385.8 0 251.96 1,385.8 461.94 461.94 2,099.7 333.38/space 2,099.7 585.39/space 0 Total 1,069,000 226,220 (11) Product cost 2,651.4 2,276 (10) Unit cost per sheets Check on (9) 3,224,367* Total activity cost 65,904 7,212 (10.57%) (3.67%) (0.32%) 2,062 0 0 (0.47%) (0%) (0%) 15,849 34,972 3,600 (3.59%) (1.95%) (0.16%) 0 0 113,098 (0%) (0%) (5.06%) 7,730 0 0 (1.75%) (0%) (0%) 0 0 56,445 (0%) (0%) (2.52%) 0 0 77,974 (0%) (0%) (3.49%) 294 6,404 59 (0.07%) (0.35%) (0.00%) 0 0 356,913 (0%) (0%) (15.96%) 5,730 7,434 61,327 (1.30%) (0.41%) (2.74%) 29,255 238,051 87,147 (6.64%) (13.26%) (3.90%) 7,247 26,890 3,520 (1.64%) (1.50%) (0.16%) 100 3,933 2,303 (0.02%) (0.22%) (0.10%) 428 16,855 9,873 (0.10%) (0.94%) (0.44%) 83,999 461,999 154,002 (19.05%) (25.73%) (6.89%) 147,495 811,236 270,416 (33.45%) (45.18%) (12.09%) 346,800 (78.65%) Direct material cost 61,137 (13.87%) * All activities in column (3) added Outsource laundry Dining 46,611 1,673,678 1,203,889 (93.21%) (53.83%) 116,843 1,032,498 (6.51%) (46.17%) 33,000 (7.48%) Hot-spring water 5,049 (0.28%) Total product cost 440,937 1,795,570 2,236,387 Total customers 1,440 56,750 33,240 Unit product cost 306.21 31.64 67.28 allocated resource costs, working sampling (Tsai, 1996) is used to estimate the percentage of time spent on each of various activities for each staff member and manager. In this way an adjusted percentage of personnel time spent on each activity can be obtained. In the first stage, resources in this country inn are assigned to all activities in five activities centers by resource drivers. In the second stage, all activities costs in the five activities centers are assigned to the three country inn’s products. Table 2 shows activities analysis and the assignment of activities to products by activity drivers. Labor, material and utility costs traced to activities are shown in columns (1)-(3) of table 2. Columns (4)-(11) present detail about how activities are allotted to each product by drivers. For example, the driver of the cleaning activity is the true cleaning time which is total 6810.6 hours. Using the driver to trace the cleaning activity to the three products separately, and assigning 2651.4 hours, 3749 hours and 410.2 hours respectively, of cleaning time, the driver can allocate NT$ 46,611 to lodging, NT$65,904 to hot spring use, and NT$7,212 to dining. Finally, adding all the allocation activities costs in each product we can get the total activity costs. The total product cost is the combination of the total activities costs, direct material costs, and outsource costs (laundry, hot spring water) in each product. Unit product cost is defined as the total product cost divided by the total number of customers. The unit product costs of lodging, hot spring use and dining are NT$ 306.21, NT$31.64 and NT$ 67.28 per customer respectively in the busy winter seasons. The lodging, hot spring use and dining products of this country inn represent three market segments. After applying ABC to the country inn case, the unit costs of each of the country inn’s products in three market segments are clear. The cost information acquired from ABC in this case is extremely useful to the inn’s owners (managers) for marketing, decision making and cost-volume-profit analysis. 5. Comparing ABC with traditional accounting Table 3 shows a comparison between ABC and the traditional accounting method. The traditional accounting system here uses direct labor hours to allocate overheads to the three inn products. Cost for a high-volume product should not necessarily be traced based on a correspondingly high level of labor hours, since, in reality, such a product may not consume a proportionally high amount of overhead. As shown in table 3, the unit cost of the three products derived from the traditional accounting method are NT$155.4 for lodging, NT$15.85 for hot spring use, and NT$100.76 for dining, per customer. If we compare the results between ABC and traditional accounting, the unit cost of lodging and of hot spring use are underestimated, but the unit cost of dining is overestimated under the traditional accounting method. This is because the traditional accounting method distorts the overheads Table 3 Comparing ABC with Traditional Accounting N.T. Dollars Product Cost Lodging Hot-Spring Dining Overhead 99,640 597,842 1,693,885 (Assigning by direct labor hours) (240hr) (1440hr) (4080hr) Direct Labor 30,000 180,000 623,000 Direct Materials 61,137 116,843 1,032,498 Outside laundry 33,000 Traditional accounting allocation: Hot-spring water Total cost on traditional accounting basis 5,049 223,777 899,734 3,349,383 Mean number of customers 1,440 56,750 33,240 Unit cost per customer 155.4 15.85 100.76 306.21 31.64 67.28 Unit cost per customer in ABC cost allocation in the three products, while the ABC system avoids this distortion by valuing the activity and driver assigning processes. 6. Conclusion After deriving the cost of each product by providing accurate and relevant information, we find that real estate costs consume the greatest proportion of the hot spring use and of lodging costs (over 50%). This is the result of the high cost of real estate in Taipei. In this case, through ABC implementation we can obtain clear and reliable information about the proportions of activities costs in every single product. Managers also can use the information derived from implementing ABC for decisions on pricing, product mix (Tsai, 1994), product design, profitability analysis, and so on. Our comparison of ABC with the traditional costing method shows that ABC method is practical and appropriate for application to the hot spring country inn and yields more accurate information for cost management and pricing decisions. Reference Ahrens, T., Chapman, C. (2002), “The structuration of legitimate performance measures and management: day-to-day contests of accountability in a UK restaurant chain”, Management Accounting Research Vol. 13 (2), pp. 151–171. Brignall, T.J., Fitgerald, L., Johnston, R., Siverstro, R. (1991), “Product costing in servic e organizations”, Management Accounting Research Vol. 2 (4), pp. 227–248. Brimson, J.A. (1991), Activity Accounting - An Activity-Based Costing Approach, John Wiley & Sons, Inc., New York, NY. Chen, Y.P. (2001), “An interview with the CFO of TSMC : talking about ABC”, Accounting Research Monthly, No. 182, pp. 52. Chenhall, R., Langfield-Smith, K. (1998), “Adoption and benefits of management accounting practices: an Australian study”, Management Accounting Research, No. 9, pp. 1-19. Clarke, P., Hill, N., Stevens, K. (1999), “Activity-based costing in Ireland: barriers to, and oppoptunities for, change”, No. 10, pp. 443-468. Cooper, R. and Kaplan, R.S. (1988), “Measure costs right: Make the right decisions,” Harvard Business Review, Vol. 66 No. 5, pp. 96-103. Cotton, W., Jackman, S., Brown, R. (2003) “Note on a New Zealand replication of the Innes et al. UK activity-based costing survey”, Management Accounting Research, No. 14, pp. 67-72. Cropper, P., Cook, R. (2000), “Activity-based costing in universities—five years on”, Public Money & Management, April-July, pp. 61-68 Dent, J.F. (1991), “Accounting and organizational cultures: a field study of the emergence of a new organizational reality”, Accounting, Organizations and Society Vol. 16 (8), pp. 705–732. Downie, N. (1997), “The use of accounting information in hotel marketing decisions”, International Journal of Hospitality Management, Vol. 16, No. 3, pp. 305-312 Ellis-Newman, J. and Robinson, P. (1998), “The cost of library services: Activity-based costing in an Australian academic library”, The Journal of Academic Librarianship, Vol. 24, No. 5, pp. 373-379. Emmanuel, C., Otley, D., Merchant, K. (1990) Accounting for Management Control, Chapman & Hall, London. Gunasekaran A., Singh D. (1999), “Design of activity-based costing in a small company: a case study”, Computers & Industrial Engineering, Vol. 37, pp. 413-416. Harris P., Brown, J. (1998), “Research and development in hospitality accounting and financial management”, International Journal of Hospitality Management, Vol. 17, pp. 161-181. Innes, J., Mitchell, F., Sinclair, D. (2000), “Activity-based costing in the U.K.’s large companies: a coparison of 1994 and 1999 survey results”, Management Accounting Research, No. 11, pp. 349-362. Lanier, P., Caples, D., Cook, H. (2000), “How big is small”? Cornell Hotel and Restaurant Administration Quarterly, Vol. 41, Issue: 5, pp.90-95. Lee, T.R., Kao, J.S. (2001), “Application of simulation technique to activity-based costing of agricultural systems: a case study”, Agricultural Systems, Vol. 67, pp. 71-82. Lievens, Y., Bogaert, W., Kesteloot, K. (2003), “Activity-based costing: a practical model for cost calculation in radiotherapy”, International Journal of Oncology·Biology· Physics, Vol. 57, No. 2, pp. 522-535. Mia L., Patiar A. (2001), “The use of management accounting systems in hotels: an exploratory study”, International Journal of Hospitality Management, Vol. 20, pp. 111-128. Noone, B., Griffin, P. (1999), “Managing the long-term profit yield from market segments in a hotel environment: a case study on the implementation of customer profitability analysis”, International Journal of Hospitality Management, Vol. 18, pp. 111-128. Pellinen, J. (2003), “Making price decisions in tourism enterprises”, International Journal of Hospitality Management, Vol. 22, pp. 217-235. Poorani, A.A., Smith, D.R. (1995), “Financial characteristics of bed-and breakfast inns”, Cornell Hotel and Restaurant Administration Quarterly, Vol. 36, Issue: 5, pp.57-63 Pirttilä, T., Hautaniemi, P.(1995), “Activity-based costing and distribution logistics management”, International Journal of Production Economics, Vol. 41, No. 1-3, pp. 327-333. Rouse, P., Putterill, M., Ryan, D. (2002), “Integrated performance measurement design sights from an application in aircraft maintenance”, Management Accounting Research Vol. 13, pp. 229–248. Sharma, D.S. (2002), “The differential effect of environmental dimensionality, size, and structure on budget system characteristics in hotels”, Management Accounting Research Vol. 13, pp. 101–130. Spedding, T.A., Sun, G.Q. (1999), “Application of discrete event simulation to the activity based costing of manufacturing systems”, International Journal of Production Economics, Vol. 58, pp. 289-301. Themido, I., Arantes, A., Fernandes, C., and Guedes, AP (2000), “Logistic costs case study-an ABC approach”, Journal of Operational Research Society, Vol. 51, pp. 1148-1157. Tsai, W.-H. (1994), “product-mix decision model under activity-based costing”, Proceedings of 1994 Japan-USA Symposium on Flexible Automation, Vol.I, Institute of system, Control and Information Engineers, Kobe, Japan, July 11-18, pp. 87-90. Tsai, W.-H. (1996), “A technical note on using work sampling to estimate the effort on activities under activity-based costing”, International Journal of Production Economics, Vol. 43 No. 1, pp. 11-16. Turney, P.B.B. (1992), "What an activity-based cost model looks like", Journal of Cost Management, Vol. 5 No. 4, pp. 54-60.