TD/B/COM.3/EM.26 Page 1 TD United Nations Conference on Trade

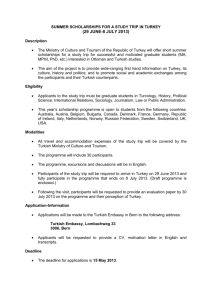

advertisement