LICENSING CASELAW

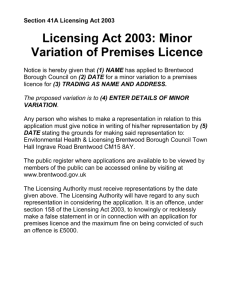

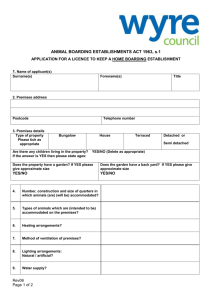

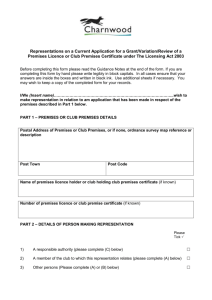

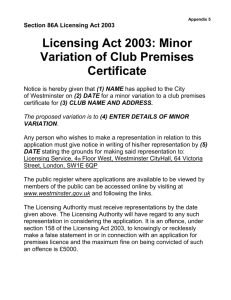

advertisement