Please do not cite, quote, or circulate without permission from the

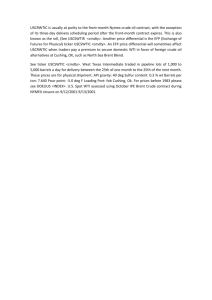

advertisement