Adams_spectacle - Passions & Tempers, a History of the Humours

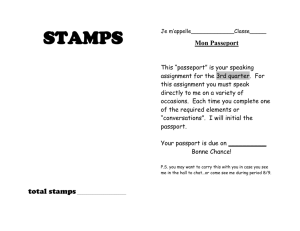

advertisement