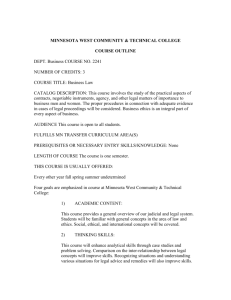

EJERCICIO DE EDICIÓN EN inglés In Burson,[1] the supreme court

advertisement

![EJERCICIO DE EDICIÓN EN inglés In Burson,[1] the supreme court](http://s3.studylib.net/store/data/008523092_1-c31fbc9eefb0a982af5b6737c64c0194-768x994.png)

EJERCICIO DE EDICIÓN EN INGLÉS In Burson,1 the supreme court upheld a decision based on a First Amendment challenge which prohibited the solicitation of botes, the display of political posters or signs, and the distribution of political campaign materials within 100 feet of the entrance to a pulling place. Justice Blackmun, joined by Justice Rehnquist and Justices White and Kennedy, representing the plurality of the Court, write an opinion in which he stated: “(t)his Court has held that the First Amendments’ hostility to content-based regulation extends not only on a particular viewpoint, but also a prohibition of public debate of topic.”2 Justice Kennedy wrote a separate concurrence, stating that, despite the preference he expressed in Simon & Schuster,3 “there is a narrow area in which the First amendment permits freedom of expression to shield to the extent necessary for the accommodation of another fundamental Right.”4 In another election contest, that of judicial elections, the Court by contrast struck down as impermissibly content-based a restriction on the subject matter of speech, this time by judicial candidates. In Republican Party of Minnesota,5 the court invalidated by a vote of 5-4 a provision of the Minnesota Code of Judicial Conduct that declared that a “candidate for a judicial office, including an current judge… [shall not] announce his or her views on disputed lawful or political issues.” In the opinion for the Court, Justice 1 Burson v. Freman, 504 U.S. 191 (1992) Id., at page 197. 3 Simon Schutter, Inc. v. Members of New York State Crime Victims Board, 502 U.S. 105 (1994). 4 Burson, 504 U.S. at 213 (Kennedy, concurring). 5 Republic of Minnesota v. White 536 U.S. 765 (2002). 2 1 Scalia wrote: “the proper text to be applied to determine the constitutionality of such a restriction is what our causes have called strict scrutiny”.6 Laws barring speech that is likely to cause a certain response in the audience based on its content are typical viewed as skeptically as direct content restrictions. For example, Forsth invalidated a scheme of calibrating the price of a parade permit to the expected hostility of the audience response.7 Likewise, Coen held that a breach-of-peace law could not be applied in order to prevent audience offense,8 and R.A.V. found content-based a ban of symbols that caused racial anger or alarm. 9 6 Id. at 774 Foryth Co. v. Nationalist Moment 505 U.S. 123 (1996). 8 Cohen v. Idaho, 403 US 15 (1971). 9 R.A.V. v. City of St. John, Minnesota, 555 U.S. 375 (1992). 7 2