Smart Choices: A Practical Guide to Making Better Decisions, John S

advertisement

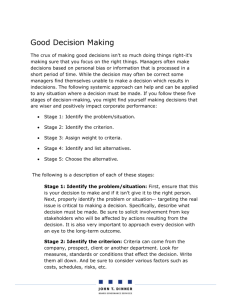

Smart Choices: A Practical Guide to Making Better Decisions, John S. Hammond, Ralph L. Keeney & Howard Raiffa, Harvard Business School Press, 1999 Pg. 4 An effective Decision Making process will fulfill 6 criteria: 1. It focuses on what’s important. 2. It is logical and consistent. 3. It acknowledges both subjective & objective factors and blends analytical with intuitive thinking. 4. It requires only as much information and analysis as is necessary to resolve a particular dilemma. 5. It encourages and guides the gathering of relevant information and informed opinion. 6. It is straightforward, reliable, easy-to-use and flexible. Pg. 19 This book is based on the PrOACT method and considers eight elements of a good decision: 1. Problem 2. Objectives 3. Alternatives 4. Alternatives 5. Consequences 6. Tradeoffs 7. Uncertainty 8. Risk Tolerance 9. Linked Decisions Define the Decision Problem Pg. 23 Pg. 24 Ask what triggered this decision. Why are you considering it? 1. Question your assumption of what the decision problem is. 2. Question the occasion that triggered the decision problem. 3. Question the connection between the trigger & the problem. Question the constraints of your problem statement. Constraints narrow the range of alternatives and they are often artificial or habitual. Identify the essential elements of the problem. Understand what other decisions impinge on or hinge on this decision. Establish a sufficient but workable scope for your problem definition. Gain fresh insights by asking others how they see the situation. Reexamine your Problem Definition as you go! Questioning the problem is particularly important when circumstances are changing rapidly or when new information becomes available. A poorly formulated decision problem is a trap! Example: Take a transfer or a job offer from another company. Don’t limit yourself what about a full-blown job search? 1 Pg. 35 Master the Art of Identifying Objectives (5 steps) 1. Write down all the concerns you hope to address through your decision. Try these techniques: Compose a wish list. Think of the worst possible outcome - what do you want to avoid? Consider the decision’s possible impact on others. What do you want for them? Ask others who faced similar situations what they considered in their decision? Consider a great - even if unfeasible - alternative. What is so good about it? Consider a terrible alternative - what’s so bad about it? Think about how you’d explain your decision to someone else. How would you justify it? Your answers may uncover other concerns. When considering a group decision - have each member consider the above alone - then meet together to discuss. Don’t limit their thoughts by meeting first. 2. Convert your concerns into succinct objectives. An objective should be a short phrase consisting of a verb and an object. E.g., Minimize Cost. 3. Separate ends from means to establish your fundamental objectives. The challenge is to distinguish between objectives that are means to an end (having leather seats in the new car) and those that are an end in themselves (having an attractive/comfortable interior). To do this, ask the question “Why” five times. Asking why will lead you to what you really care about. Separating means is important because each plays an important - but different role. Each means objective can serve as a stimulus for generating alternatives and can deepen your understanding of your decision problems. Only fundamental objectives can/should be used to evaluate and compare alternatives. 4. Clarify what you mean by each objective. Ask: What do I mean by this? What enables you to clearly see the components of your objective which in turn helps you state it more precisely and see how to reach it. At decision time, you can more easily tell if the alternative will meet the objective. 5. Test your objectives to see if they capture your interests. Practical Advice for Nailing down your Objectives: 1. Objectives are personal - different people facing identical situations may have very different objectives. 2. Different objectives will suit different decision problems - it is very important to reformulate your objectives for different decisions - don’t use the same objectives to hire a CFO that you would to hire a VP of Sales. 3. Availability or ease of access to data should not limit objectives. It is easy to focus on the immediate, tangible, and measurable when listing objectives. These may not reflect the essential problem. Using easy to measure but only partially relevant objectives is like looking for a lost 2 Pg. 47 wallet under a street lamp because there’s more light - although you lost it in a dark alley. 4. Unless circumstances change markedly, well thought out objectives for similar problems can remain relatively stable over time. 5. If a prospective decision sits uncomfortably in your mind - you may have overlooked an important objective. Alternatives Pg. 47 First - you can’t select an alternative you didn’t consider. Second - no matter how many alternatives you have - your final choice can be no better than the best of the lot. Don’t box yourself in with limited alternatives. Pg. 48 Pg. 50 Pg. 56 Common Mistakes: Business as usual. Laziness and an over reliance on habit often cause you to select business as usual. With a modest amount of effort - attractive new alternatives can be found. Incrementalizing. Small and usually meaningless changes to existing alternatives do not create new alternatives. Default alternatives. Picking the first alternative because it is easier than generating new ones causes this. First possible solution. Selecting the first partial solution just because it works does not mean that it is the best solution. Alternatives presented by others. Choosing alternatives presented by others is easy but hardly guarantees the selection of the best alternative. Waiting too long. Waiting too long can cause options to expire leaving you to choose from the alternatives that are left. Keys to generating better alternatives: Using your objectives - ask how? Challenge decision constraints. Why must something be done in 90 days? Determine if the constraints are real or assumed. Try to assume that the constraints don’t exist - what new alternatives are possible? Set high aspirations. This forces out-of-the-box thinking and clears the status quo. Do your thinking first before getting opinions from others - they might anchor your unnecessarily. Learn from experience. Do some research. Ask others for suggestions. Tailor your alternatives to your problem. There are four basic types of alternatives. 1. Process Alternatives. Process alternatives help ensure fair decisions involving conflicting interests and can help preserve and foster long term relationships. These include: voting, binding arbitration, standardized test scores (to establish minimum requirements) sealed bids and auctions. 2. Win-win-alternatives. Help others help you. 3. Information gathering alternatives. In situations with a high degree of 3 uncertainty, these give you time and room to maneuver. 4. Time-buying alternatives. When you’re uncomfortable deciding now - question the time constraints. Just be sure that you identify which alternatives expire over time and that will help you identify the cost of waiting. Pg. 65 Pg. 66 Pg. 67 Pg. 71 It’s also important to know when to quick looking. Consequences. Be sure that you really understand the consequences of your alternatives before you decide. Describe consequences with appropriate accuracy, completeness and precision. Build a Consequences Table (4 Steps) 1. Mentally put yourself into the future and describe in detail the outcome of a decision. 2. Create a free form description of the consequences of each alternative. Use the words and numbers that best capture the key characteristics. Gather hard information but also express subjective judgements. Use numbers when appropriate otherwise use words, graphics, diagrams, photos. If they are relevant and can be used consistently. Check your description against your list of objectives. Does the description consider all objectives? 3. Eliminate all clearly inferior alternatives. Use one alternative (probably the status quo) as the tentative king. Compare each alternative to it and eliminate those that are inferior. Compare pros & cons - if one is superior - then it becomes the king and you eliminate the original king. 4. Organize descriptions of the remaining alternatives into a consequences table. ROWS=Objectives & COLUMNS=Alternatives. Mastering the Art of Describing Consequences. Try before you buy. Use common scales to describe the consequences. Scales must represent measurable, meaningful categories that capture the objective ($’s, %, size, time, volume). Two ways to measure intangibles: 1. Select a meaningful scale to capture the essence of the objective. Example, to measure a flexible schedule - represent the % of hours that can be flexed. 2. Construct a subjective scale to measure your object A through F, 1 through 10, 1 to 100. Don’t rely solely on hard data. Give due recognition to objectives that can’t be measured by hard data. Choose scales that are relevant - REGARDLESS of hard data available. Make the most of valuable information. Use experts wisely. Choose scales that reflect an appropriate level of precision. Don’t imply a level of precision, above what’s available. If you show a cost estimate as $33,475 it is too precise - $33,000 +/- 10% is better. 4 Pg. 85 Address major uncertainty head on. Tradeoffs Dominance eliminates alternatives. Even Swaps eliminates objectives. Find and eliminate dominated alternatives. Make tradeoffs using even swaps. If all alternatives are rated equally for a given objective then you can ignore that objective in choosing among those alternatives. If they are not - consider - 1st determine the change necessary to cancel out an objective 2nd assess what change in another objective would compensate for the needed change. EXAMPLE: If you had a business where profit was $20M and market share was 20%. You have two objectives, profit and market share. You have two alternatives - establishing a new line or opening a new office. Alternative Objective NEW LINE NEW OFFICE Profit $25 M $10M (due to startup costs) Market Share 21% 26% After consideration - $15M profit from the new line would make it equal to that generated by the new office. You decide that $15M less in profit is worth about 3% market share. So the revised measure is as follows: Alternative Objective NEW LINE NEW OFFICE Profit $10M $10M (due to startup costs) Market Share 24% 26% As you can see - when the profit objective is equal - the market share measurement makes the choice. Pg. 99 Simplifying a complex decision with even swaps is the key. Practical Advice for making Even Swaps: Make easier swaps first. Concentrate on the amount of the swap NOT on the perceived importance of the objectives. Value an incremental change based on what you start with. For example: adding 300 sq.ft. to a cramped 700 sq.ft. office is very valuable - but - adding 300 sq.ft. to a spacious 1,000 sq.ft. office is less valuable. Don’t just look at the size of the slice - look at the size of the pie. Make consistent swaps. Although swaps are relative - they should be logically consistent. Example. If you would swap A for B and B for C then you should be willing to swap A for C. Seek out information to make informed swaps. Practice at tradeoffs makes perfect. 5 Pg. 110 Pg. 112 Pg. 114 On uncertainty: Distinguish choices from good consequences. A smart choice - a bad consequence -- it happens. A poor choice - a good consequence -- luck. Decisions under uncertainty must be judged by the quality of the decision - not by the quality of the outcome. Use Risk Profiles to Simplify Decision Involving Uncertainty A risk profile captures the essential information about the way uncertainty affects an alternative. It answers 4 key questions: 1. What are the key uncertainties? 2. What are the possible outcomes of these uncertainties? 3. What are the chances of occurrence of each possible outcome? 4. What are the consequences of each outcome? Example: Risk profile for submitting a proposal: Uncertainty = Government response to our bid. OUTCOME CHANCE CONSEQUENCES A. No Contract Least Likely Bad. Would have to reduce staff & scramble for small business. B. Partial Contract Most Likely Pretty good. More stability & good profit. C. Full Contract Possible Wonderful. Very profitable. Significant benefit for image. How to construct a risk profile. Identify key uncertainties. List all uncertainties that might significantly influence consequences at all. Consider uncertainties one at a time and determine the degree to which their various outcomes might influence the decision. Define outcomes. Specify the possible outcome for each uncertainty. How many must be defined to represent the extent of each uncertainty? How can each outcome best be defined? Assign chances. Use your judgement - for reasonable guesses. Consult existing information. Collect new data if needed. Ask experts. Break uncertainties into their components if too big. Don’t use unlikely, toss-up, pretty-good chance, etc… they are too subjective. Use % instead. If it’s tough - bracket the % - is it >50% or less? If it is between 30% & 50% - consider whether 40% is descriptive enough? Clarify the consequences. Depending on the complexity of the decision, you can use one of 3 ways. 1. A written description - least precise - it may occasionally be good enough. 2. Qualitative description by objective - include more information than simple descriptions. They break consequences into their constituent parts - an outdoor picnic is 1st high on fun, 2nd high on family involvement and 3rd lower in cost. 6 Pg. 123 3. Quantitative Description by objective - $5,000 +/- 10%. Picture Risk Profiles with Decision Trees. When a risk profile by itself doesn’t make the smart choice obvious - decision trees can be very helpful. Alternatives Hotel Dinner Dance Uncertainty Consequences FUN FAMILY EXPENSE Rain 30% Med Med $12.5K Sun 70% High Med $12.5K Rain 30% Low Low $7K Sun 70% High High $6K 2 1 Picnic 3 A BOX indicates a decision and a CIRCLE indicates uncertainty. Making a decision tree on simple problems makes it easier when working on a complex one. Pg. 137 Understand your willingness to take risks. Risk Tolerance = your willingness to risk loss for possible improved consequences. The basic principle of a risk profile is this: The more desirable the better consequences of a risk profile - relative to the poorer consequences - the more willing you will be to take the risk necessary to get there. Pg. 139 Making the SMART CHOICE requires balancing the desirability of the possible consequences with the probabilities that they will occur. Incorporate your Risk Tolerance into your Decisions (3 Steps): 1. Think hard about the relative desirability of the consequences for an alternative under consideration. 2. Balance the desirability of the consequences with their chances of occurring. 3. Choose the most attractive alternative. 7 Pg. 140 Quantify Risk Tolerance with Desirability Scoring (4 Steps): 1. Assign Desirability Scores to all Consequences. Assign 100 to the best consequence and 0 to the worst. Then assign a score to each remaining consequence that reflects its relative desirability. Make sure that your consequence score is consistent. 2. Calculate each consequence contribution to the overall desirability of the alternative. Outcomes with a low probability of occurring should have less influence on an alternative’s overall desirability. So, multiply the probability by its desirability score. Example: If the best consequence (Desirability = 100) has a probability of 30% then the Consequence Contribution is 30 (100 * .3). 3. Calculate each alternative’s overall desirability score. Add all of the contributions to get a total score for the alternatives. 4. Compare the overall desirability scores associated with each alternative and then choose. Example: you have to choose between an Accounting Firm and a Consulting Firm. Both Jobs are about equivalent. The uncertainty in the choice is which office they’ll assign you to. So, first consider each alternative and the probability of each outcome within the alternative. ALTERNATIVE: Accounting Firm UNCERTAINTY: Office Assignment Consequences Desirability Outcome Chance Living Job Society Contribution to overall Desirability 80 NY 90% Very Good Excellent Fair (80 x .9) 72 0 worst Santiago 10% Poor Fair Excellent (0 x .1) 0 Contribution to overall Desirability ALTERNATIVE: Consulting Firm UNCERTAINTY: Office Assignment Consequences Desirability Outcome Chance Living Job Society 50 Buenos Aires 75% Good Good Very Good (50 * .75) 37.5 100 Best London 25% Excellent Excellent Good (100 * .25) 25 In this example 72 is the top Contribution to Desirability - so the smart choice is the Accounting Firm. 8 Pg. 154 Pg. 157 Pg. 163 Pg. 165 Watch out for Pitfalls when making decisions: Don’t over focus on the negative. Don’t fudge the probabilities to account for risk. You’ll make your data too pessimistic. Don’t ignore significant uncertainty. Avoid foolish optimism. Don’t avoid risky decisions because they are complex. Make sure subordinates reflect the organization’s risk tolerance in decisions. Open New Opportunities by Managing Risk (5 ways) 1. Share the risk with others. 2. Seek risk-reducing information. 3. Diversify the risk. 4. Hedge the risk. 5. Insure against risk. Example: Harry Healy runs a business drilling and producing shallow natural gas wells. The cost is $125,000. The risk is 1st that a well may or may not produce, 2nd that the price of gas can fluctuate by as much as 300% per year. The risk of production is as follows: 10% = no gas, total loss, 30% = recover only a small amount of the $125K, 20% = lose only a small amount, 10% = break even, 30% = make money. So only 40% of the time Harry can preserve his investment. Here’s what Harry does: 1. Share the risk. Harry never invests more than $25K in a well and he stands to keep 20% and share 80% with other investors who are risking $100,000.00. 2. Seek risk-reducing information. Harry hires a geologist for $12K to do a seismic test to reduce some of the uncertainties. 3. Diversify the risk. Harry puts some of his life savings in stocks and others in bonds to spread his risk. 4. Hedge the risk. To manage the risk of price fluctuations of 300%, Harry buys options to sell 50% of his gas at a fixed price so only 50% is at risk. 5. Insure against risk. Harry carries business insurance against explosions. On Linked Decisions: In linked decisions, the alternatives selected today create the alternatives available tomorrow and affect the relative desirability of those future alternatives. In linked decisions you find: A basic decision that must be addressed now. The desirability of each alternative is influenced by uncertainty. Relative desirability is influenced by a future decision that would be made after the uncertainty in the basic decision is resolved. An opportunity exists to obtain information before making the basic decision. This information could reduce the uncertainty in the basic decision and, one would hope, improve the future decision - but at a cost in money & time. 9 Pg. 166 Pg. 18 Pg. 173 The typical Decision Making pattern is a string of decide, then learn; decide, then learn more; decide, then learn; and so on… Make Smart Linked Decisions by Planning Ahead. The decision linked to a basic decision can take two forms: 1. Information Decisions - pursued before making the basic decision. They are linked because the information you obtain helps you make a smarter choice in the basic decision. 2. Future Decisions - are made after the consequences of a basic decision become known. They are linked because the alternatives that will be available in the future depend on the choice made now. The essence of making smart linked decisions is thinking ahead. By plotting your decision as a "decide-learn" sequence - you are able to clarify the sequence of decisions and see how each will influence the other. Six Steps to Analyzing Linked Decisions: 1. Understand the basic decision problem. Follow the basic process - define the core issues: problem, objectives, alternatives, uncertainties and consequences. The consequences are the crux of linked decisions. Draw up the list of uncertainties. Narrow the list down to the few that most influence the consequences. These uncertainties are candidates for developing risk profiles. 2. Identify ways to reduce critical uncertainties. List the kinds of info that could reduce uncertainty. Think of ways to obtain the important information. 3. Identify future decisions linked to the basic decision. To id relevant future decisions, you need to ask what decisions would naturally follow from each alternative in the basic decision. 4. Understand the relationships in linked decisions. Draw a decision tree to represent the links between choices and learned information in sequences. Here are a few suggestions: Get the timing right. Correct sequencing is very important. Sketch the essence of the decision problem. Describe the consequences at the end-point. 5. Decide what to do in the basic decision. Start at the end - lop off branches representing alternatives you don’t want. 6. Treat later decisions as new decision problems. Keep your options open with Flexible Plans. Flexible plans keep your options open. They can take a number of forms: All-weather plans. Work well in most situations, but they are seldom the optimal choice for any one situation. This is a compromise strategy. In highly volatile situations where the risk of outright failure is great, an allpurpose plan is often the safest plan. Short-Cycle Plans. With this strategy you make the best choice at the outset then reassess that choice often. E.g., 1 year plan reviewed quarterly. Option Wideners. This approach requires that you act in a way that expands your future options. E.G., Buy 90% from one source and 5% from each of 2 other sources to develop alternate suppliers in case of a 10 Pg. 189 Pg. 191 problem with your primary. Be Prepared Plans. A backup plan stresses preparedness. Psychological Traps These represent the 8 most common & serious errors in Decision Making: 1. Working on the wrong problem. 2. Failing to ID your key objectives. 3. Failing to develop a range of good creative alternatives. 4. Overlooking crucial consequences of your alternatives. 5. Giving inadequate thought to tradeoffs. 6. Disregarding uncertainty. 7. Failing to account for your risk tolerance. 8. Failing to plan-ahead when decisions are linked over time. MISTAKE: Over relying on First Thoughts - The Anchoring Trap Consider two questions: 1) Is the population of Turkey more or less than 35 million? 2) What is the population of Turkey? As you can see, the first question anchored your thinking and biased your consideration of question number 2. Pg. 191 What can you do? View a decision problem from different perspectives and then reconcile any differences in their implications. Think it out first before getting advice. Seek information and opinions from a variety of people. Don’t anchor others with too much of your thinking. Prepare well before negotiating - you’ll be less susceptible to anchoring tactics. MISTAKE: Keeping on Keeping on - The Status Quo Trap The status quo is too comfortable. What can you do? Remind yourself of your objectives and examine how they are served by the status quo. Never think of the status quo as the only alternative. Would you choose the status quo if it weren’t the status quo? Avoid exaggerating the effort or cost involved in switching from the status quo. Put the status quo to a rigorous test - don’t simply compare how the status quo is with how the other alternatives would be. Things change with the status quo too. If multiple good alternatives exist - don’t choose the status quo simply because it is tough to pick from the alternatives. 11 Pg. 195 MISTAKE: Protecting Earlier Choices - The Sunk Cost Trap Example: You just fixed your car for $3,000. Now one month later you are faced with another $1,500 repair. Don’t just decide to fix the car to protect the $3,000 you just spent. Check your other alternatives. Pg. 198 What can you do? Seek out and listen carefully to the views and arguments of people uninvolved with the earlier decision and hence are not committed to the original decision. Examine WHY admitting to an earlier mistake distresses you. Ego’s not a good idea. Warren Buffett: “When you find yourself in a hole, the best thing you can do is stop digging.” If you’re worried about being second-guessed by others - make this consequence an explicit part of your decision process. Consider how you’d explain your choice to those people. If you fear sunk-cost biases in your subordinates, pick one who was previously uninvolved to make the new decision. MISTAKE: Seeing what you want to see - The Confirming Evidence Trap Pg. 203 What can you do? Get someone you respect to play the devil’s advocate. Be honest about your motives. Are you really gathering information to help you make a smart choice or are you just looking for confirming evidence? Expose yourself to conflicting information. Don’t ask leading questions that invite confirming evidence. MISTAKE: Posing the Wrong Question - The Framing Trap Two types of frames that frequently distort decision making: 1. Framing as gains vs. losses. 2. Framing with different reference points. What can you do? Remind yourself of your fundamental objectives and make sure that the way you frame your problem advances them. Don’t automatically accept the initial frame whether it was formulated by you or by someone else. Reframe the problem different ways. Look for distortions caused by the frame. Pose problems in a neutral way - which is redundant and combines gains & losses or embraces the different reference points. Think hard about the framing. At points throughout and towards the end ask yourself how your thinking would change if the frame changed. 12 Pg. 204 When your subordinates recommend decisions - examine the way they framed the problem. Challenge them with different frames. MISTAKE: Being too sure of yourself - The Overconfidence Trap. Pg. 206 What can you do? Avoid being anchored by an initial estimate. Consider the extremes (low & high) first when making a forecast or judging probabilities. Actively challenge your own extreme figures. Try hard to imagine circumstances in which the actual figures would fall below your low or above your high & adjust accordingly. Challenge any expert’s or advisor’s estimates in a similar fashion. MISTAKE: Focusing on Dramatic Events - The Recallability Trap. Pg. 208 What can you do? Examine your assumptions so that you aren’t swayed by memorability distortions. Get statistics - don’t rely on memory. Break it down and make an informed guess. MISTAKE: Neglecting Relevant Information - The Base Rate Trap Pg. 209 What can you do? Don’t ignore relevant data - consider base rates explicitly in your assessment. Don’t mix up one type of probability statement with another. Don’t mix up the probability that a librarian will retire with the probability that a retiring person is a librarian. MISTAKE: Slanting Probabilities & Estimates - The Prudence Trap Pg. 209 What can you do? State your probability & give estimates honestly. Don’t adjust for prudence or anything else. Document the information and reasoning used in arriving at your estimates so others understand them better. Emphasize the need for honest input from contributors. VARY an estimate over a range and assess its impact on the final decision. Think twice about the most sensitive estimates. MISTAKE: Seeing Patterns where NONE Exist - Outguessing Randomness Trap What can you do? Don’t try to outguess random phenomena. If you see patterns - check your theory in a setting where the consequences aren’t too significant (e.g., try a system to beat the stock market on historical data first). 13