On behalf of IBM, Vermont Roundtable, Vermont Chamber of

advertisement

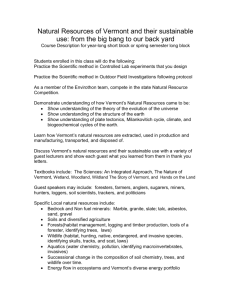

Comments on the Vermont Electric Energy Efficiency Potential Study Submitted on behalf of Associated Industries of Vermont Greater Burlington Industrial Corporation Home Builders and Remodelers Association of Vermont International Business Machines, Inc. Lake Champlain Regional Chamber of Commerce Vermont Business Roundtable Vermont Chamber of Commerce Vermont Grocers' Association Vermont Retail Association Vermont Ski Areas Association May 3, 2006 TABLE OF CONTENTS Executive Summary 1. Introduction and Summary ......................................................................................... 1 A. Efficiency Utility Budget Framework........................................................................ 1 B. Purpose of Technical Potential Study ........................................................................ 3 C. Findings of the Commenting Parties .......................................................................... 3 2. Increasing the EU Budget Will Harm the Vermont Economy ................................. 4 A. Improved Competitiveness Requires Truly “Least-Cost” Investments ..................... 5 B. Need to Assess Non-Energy Operational Improvements ........................................... 5 C. Adverse Economic Impacts of Higher Electric Rates ................................................ 6 D. The Ability to Capture Energy Efficiency Improvements Outside Vermont ............ 8 3. Measuring the Economic Benefits of Lower Energy Bills ......................................... 8 4. Funds Collected for the EU are not Used in an Economically Efficient Manner . 10 A. Market Barriers to Improved Energy Efficiency ..................................................... 10 B. Inefficiency Created by the Discrepancy Between Avoided Costs and Rates ......... 11 C. The Efficiency of the Marketplace ........................................................................... 12 5. Modeling Flaws in the Technical Potential Study .................................................... 13 A. Cost-Effectiveness vs. Least-Cost............................................................................ 14 B. Flaws in the Technical Potential Study’s Avoided Cost Models ............................. 19 C. The Failure to Address Uncertainty ......................................................................... 20 D. Erroneous Non-Economic Benefits Estimates ......................................................... 22 6. Conclusions and Recommendations .......................................................................... 23 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY On behalf of the Associated Industries of Vermont, the Greater Burlington Industrial Corporation, Home Builders and Remodelers Association of Vermont, International Business Machines, Inc., the Lake Champlain Regional Chamber of Commerce, the Vermont Business Roundtable, and the Vermont Chamber of Commerce, the Vermont Grocers' Association, the Vermont Retail Association, and the Vermont Ski Areas Association (collectively “the Commenting Parties”) we are pleased to submit these comments on the Draft Report: Vermont Electric Energy Efficiency Potential Study (“Technical Potential Study” or “the Study”) to the Vermont Public Service Board (“PSB” or “the Board”). The intended purpose of the Technical Potential Study is to identify the magnitude of all cost-effective energy efficiency savings that could be obtained and estimate the annual Efficiency Utility (“EU”) budget necessary to capture those savings, based on assumptions regarding the relative contributions between the EU and Vermont ratepayers. The Study estimates that capturing all cost-effective energy efficiency savings will require a two- to three-fold increase in the current EU budget. The Study also concludes that such a budget increase will reduce total electric consumption in Vermont by almost 20 percent below current load forecasts by the year 2015 and provide significant environmental and economic benefits. The Commenting Parties disagree with the conclusions in the Technical Potential Study, which form the basis for potential increases in the EU budget, for the following reasons: First, in contrast to the conclusions made in the Technical Potential Study, increasing the EU budget will disproportionately harm Vermont businesses, not help them. Vermont already has the highest per capita tax burden of all 50 states. Increasing the EU benefits charge to accommodate a higher EU budget will increase this tax burden and further disadvantage Vermont businesses, which already labor in a high tax, high cost environment. Second, electric rates matter as much, or more than, bills. Rates are a critical factor in the decisions made by Vermont businesses to expand operations in state and create new employment opportunities, or to expand outside the state and send jobs elsewhere. Third, markets are far more efficient allocators of scarce economic resources than are governments. Yet, because of the multiple, and competing, objectives that must be satisfied under 30 V.S.A. § 209(d), the EU budgeting process cannot be as efficient as the market. EX-1 Fourth, the mechanical aspects of the Technical Potential Study, which form the basis for recommendations to increase the EU budget, suffer from significant methodological flaws. By basing budget estimates on a costeffectiveness standard, the Study has failed to identify a least-cost solution. Moreover, the avoided cost approach used to identify maximum achievable cost-effective savings suffers from numerous flaws. Not only do some of the assumptions used appear inconsistent, the approach also fails to account for the very real impacts of market and non-market uncertainties. These inconsistencies need to be examined in more detail. Given the limited time the Commenting Parties have had to review the specific models developed by the authors of the Technical Potential Study, we ask the Board to delay the schedule so as to provide more time for us to review those models. The Commenting Parties recognize the benefits of improved operating efficiency, including improved energy efficiency. Having to compete in a global economy, the individual businesses represented by the Commenting Parties are well aware of the need to seek out efficiencies continually. It is for this overarching reason that the Commenting Parties oppose any budget increase for the EU. We believe there are alternatives to increasing the EU budget and raising rates for business customers, and we urge the Board to explore such alternatives. EX-2 1. Introduction and Summary On behalf of the Associated Industries of Vermont, the Greater Burlington Industrial Corporation, International Business Machines, Inc., the Lake Champlain Regional Chamber of Commerce, the Vermont Business Roundtable, and the Vermont Chamber of Commerce, the Vermont Grocers' Association, the Vermont Retail Association, and the Vermont Ski Areas Association (collectively “the Commenting Parties”) we are pleased to submit these comments on the Draft Report: Vermont Electric Energy Efficiency Potential Study (“Technical Potential Study” or “the Study”) to the Vermont Public Service Board (“PSB” or “the Board”). These comments have been prepared by Dr. Jonathan Lesser, of Bates White, LLC, an economic and business consulting firm, and have benefited from review and input of the Commenting Parties. Dr. Lesser is an economist with extensive experience in the energy field, both in Vermont and elsewhere. He was previously employed by Green Mountain Power as the Manager, Economic Analysis, and also served as the Director of Planning at the Vermont Department of Public Service. Dr. Lesser has testified before public utility commissions in Alaska, Arkansas, Connecticut, Illinois, Oklahoma, Rhode Island, Vermont, and before the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission (FERC). These comments discuss specific issues and concerns we have with the Technical Potential Study, as well as issues regarding increasing the EU budget and how the Board must balance the three objectives established by the Legislature in Act 61. We believe it is important to consider all of these issues jointly, as they are closely linked. A. Efficiency Utility Budget Framework In 2005, the Vermont Legislature passed, and the Governor signed into law, Act 61. One section of that Act modified 30 V.S.A. § 209(d), which had previously set a cap of $17,500,000 for the amount that could be collected from Vermont’s electric customers to fund the Efficiency Utility (“EU”). Specifically, 30 V.S.A. § 209(d) was modified to state that the EU budget will be established by the Board, in a manner that is “consistent with the principles of least cost integrated planning as defined in section 218c of this title.” Moreover, in establishing the EU budget and how it is allocated among different customer groups, the Board is to balance three different objectives: 1. “Providing efficiency and conservation as part of a comprehensive resource supply strategy;” 2. “Providing the opportunity for all Vermonters to participate in efficiency and conservation programs;” and 1 3. “The value of targeting efficiency and conservation efforts to locations, markets, or customers, where they provide the greatest value.” (emph. added). Thus, the Board must set a EU budget that balances these different objectives while maintaining consistency with the least-cost planning guidelines of 30 VSA § 218c. These three objectives are not entirely coincident. As a result, the Board must determine how much weight each should receive. For example, were the Board to place the entire weight on the third objective, EU programs might be designed with a much greater emphasis on programs in the Chittenden County area, which is experiencing more rapid load growth than other parts of Vermont. This could conflict with the second objective, which calls for opportunities for all Vermonters to have an opportunity to participate in energy efficiency programs. The Legislature did not establish specific guidelines as to how the Board is to balance these objectives. For example, it’s not clear how much weight should be given to the third objective, which is arguably focused most closely on pure economic efficiency and which we believe to be the most important underlying value to be considered, given the cost challenges Vermont businesses face. It is also not clear whether the Board must develop any sort of objective criteria for balancing the three objectives, nor how the success or failure in meeting those objectives will be measured. However, it makes no economic sense to establish an overall EU budget before determining those weighting factors, because it is those factors that will determine the overall cost-effectiveness of the funds spent by the EU.1 Without some guidance as to the weights, the Board cannot establish an “efficient” EU budget. For example, suppose the second objective, which addresses equity in the form of program access by all Vermonters, is given the most weight.2 In that case, more emphasis would be given to programs that necessarily will be less-cost effective than targeting DSM efforts where they provide the greatest value.3 In effect, the more the Board emphasizes this second goal, the greater the upward shift in the energy efficiency supply curves. Capturing energy efficiency savings will become more costly and less efficient because the EU will not be concentrating its efforts on capturing the most cost-effective energy efficiency savings. 1 There are established mathematical techniques that can be used to solve these so-called “multi-attribute” or “multi-objective” capital budgeting problems. 2 The Commenting parties believe that the second legislative objective has been met by the Board, because all Vermonters have had an opportunity to participate in efficiency and conservations programs since the inception of the EU and the program already receives significant funding. 3 This presupposes that the “avoided-cost” approach used to identify all cost-effective energy efficiency is correct. As discussed in Section 5, however, this approach suffers from fundamental economic flaws. 2 Therefore, the Commenting Parties believe the Board should place by far the greatest weight on meeting the third objective established by the Legislature.4 B. Purpose of Technical Potential Study The intended purpose of the Technical Potential Study is to identify the magnitude of all cost-effective energy efficiency savings that could be obtained and estimate the annual EU budget necessary to capture those savings, based on assumptions regarding the relative contributions between the EU and Vermont ratepayers. Specifically, the Study states “It is clear that to achieve all of the maximum achievable cost effective savings, Efficiency Vermont … would have to spend over $385 million in today’s dollars (this figure includes financial incentives) over the next decade to achieve such results (or $38.5 million a year in 2006 dollars, assuming the EVT pays 50% of measure incremental costs)” (emph. in original, fn. omitted).5 The Study further concludes that this $38.5 million annual value6 would need to be increased by at least $15.4 million if Efficiency Vermont “had to pay 100% of measure incremental or full costs to obtain maximum achievable cost effective potential savings levels.”7 This equates to a $53.9 million dollar annual budget,8 a three-fold increase over the previous budget ceiling. The Technical Potential Study concludes that such large increases in EU expenditures will not only reduce total electric consumption in Vermont by almost 20 percent below current load forecasts by the year 2015, but will also provide significant environmental and economic benefits. C. Findings of the Commenting Parties The Commenting Parties disagree with the conclusions in the Technical Potential Study because they are based on unsupported assumptions and a modeling framework that appears to have significant flaws. The increases in spending on the EU identified in the Study cannot be justified economically, would further damage the competitiveness of Vermont businesses and industry, and adversely affect Vermont’s already tenuous economy, which 4 Distribution utilities and VELCO retain separate energy efficiency responsibilities, independent of the EEU, related to network planning and the potential use of DSM as a “distributed resource.” The Technical Potential Study did not address these efforts, nor their potential cost, which add to the Commenting Parties rate impact concerns. 5 Technical Potential Study, at 7. effectiveness” concept. Below, we discuss problems with the entire “cost- 6 In an email dated April 20, 2006 from Mr. Riley Allen, Mr. Allen states that the quoted budget figure is erroneous and should be $30 million per year. 7 Ibid. 8 This equates to just over $45 million, based on Mr. Allen’s email. 3 labors under the highest overall tax burden per person of all 50 states. That tax burden now stands at $3,600 per year, which stands in stark contrast to New Hampshire, which imposes a per capita tax burden of only $1,544, the third lowest in the nation. 9 The Commenting Parties oppose any increases in the EU budget that will further increase the tax burden on the business community. The Commenting Parties represent the majority of Vermont businesses, many of which are struggling to maintain their Vermont operations. In the last few years, a number of businesses have expanded elsewhere or closed because they cannot compete in Vermont’s high-cost business environment.10 Our comments regarding the Technical Potential Study do not mean that the Commenting Parties oppose improvements in energy efficiency. We are acutely aware that, to maintain our competitiveness in a global market, the businesses and industries we represent must always seek out ways to improve the efficiency of our operations. We are continually examining strategies to improve efficiency, whether it is our manufacturing processes, employee utilization, marketing effectiveness, or energy use. Finally, the Commenting parties believe there are alternatives to increasing the EU budget that deserve further exploration and development, such as voluntary “opt-ins,” revolving loans, and shared savings contracts, all of which could be provided by the EU, other vendors, or through other policy approaches. We believe such alternatives can capture energy efficiency savings at a lower overall cost, by harnessing the power of the market. We recommend that the Board explore these and other alternatives as part of its deliberations on the EU budget for the next three years. 2. Increasing the EU Budget Will Harm the Vermont Economy Raising the EU budget will impose higher taxes on all Vermont’s business community, which is already struggling to maintain its competitiveness. There is little disagreement among economists that increasing marginal tax rates, especially when those rates are already high, reduces economic growth. As a result, doubling or trebling the EU budget will not create thousands of jobs, as the figures cited in the Technical Potential Study imply.11 More likely, it could eliminate existing jobs that Vermont can ill afford to lose. Proponents of an increased EU budget may point to the Study’s contention that investments in energy efficiency “can make businesses in Vermont more competitive with businesses in 9 Source: U.S. Census Bureau, Governments Division, March 29, 2006. 10 See, e.g., Testimony of Robert Lang, International Business Machines, Inc., Before the Senate Finance Committee, February 1, 2005, in reference to IBM’s decision to expand production levels in Bromont, Quebec, rather than in Essex Junction, Vermont because of high electricity costs. 11 Section 3 below discusses some of the analytical flaws with the economic impact studies cited by in the Technical Potential Study 4 other states and other countries,”12 to refute our claim of economic harm. They may argue that competitiveness will be improved because investing in energy efficiency reduces energy bills. However, having analyzed this argument, the Commenting Parties reject it, because it fails to account for at least four other important economic factors. A. Improved Competitiveness Requires Truly “Least-Cost” Investments Investments in energy efficiency will improve business competitiveness only if those investments truly are “least-cost.” Clearly, spending two dollars to save one is no bargain. Under the current EU structure, all ratepayers must decide whether to “opt-in” to invest in energy efficiency. For example, IBM currently pays about $900,000 per year to the EU. To receive any of that money back, it must decide to install energy efficiency measures and then have those measures verified by the EU. Under IBM’s current agreement, it can only receive at most 70 percent of its EU contribution back. In other words, IBM pays an effective minimum 30 percent tax on all of its contributions. Since a larger EU budget will impose a higher tax burden on all businesses, any business must be able to “opt-in” sufficiently to EU programs to overcome the adverse economic impacts of the higher EU charges on its electric bill. Ironically, raising the EU charge will further penalize the most energy efficient businesses that already have invested in energy efficiency and will thus have fewer least-cost measures available for which they can “optin.”13 Moreover, the rational reaction in such cases is for businesses to stop their own investment in energy efficiency measures and instead channel them through government programs, thus exacerbating free-rider effects. Furthermore, the EU programs only create “least-cost” investments to the extent that the companies that contribute relatively more to the EU budget are those that have more room to make energy efficient investments. The Study’s authors do not explain why this would be the case. In fact, as we explained above, the opposite would happen if large industrial customers have already exhausted most of the DSM measures available. In attempting to recoup their contributions, these companies would make unnecessary investments, while relatively small customers with more energy-saving opportunities would have little incentive to invest. B. Need to Assess Non-Energy Operational Improvements Even if an energy efficiency investment is “least-cost” among all possible such investments, it must still be compared with other investment opportunities, so that a business can maximize overall improvements in economic efficiency. This is called the capital budgeting 12 Technical Potential Study, at 81. 13 The Study also fails to address the fact that, while it has based energy efficiency costeffectiveness on a societal test, businesses and individuals all will decide to opt-in based on the retail rates they pay. This is discussed further in Section 4, below. 5 problem and is fundamental to any business. Given finite investment resources, any business will allocate those resources to provide the greatest overall returns. Those may be through energy efficiency or they may involve far different investments. Increasing the EU tax, however, forces energy efficiency investments to take priority over other operating efficiency improvements. Not only does that create losses for Vermont businesses that would choose to invest in other operational improvements, the entire tax and “opt-in” approach to efficiency investments implies that the government has a better understanding of how Vermont’s businesses can best improve their operating efficiency than the businesses themselves. We reject this proposition. Forcing energy efficiency investments to take priority over other operating efficiency improvements distorts business investment decisions. That causes economic harm by imposing what economists call a “second-best” solution. By raising the EU tax on business customers, Vermont will reduce the amount of available capital firms have to invest. That will cause economic harm in itself, just as any tax increase causes economic harm to an individual firm. Then, however, when the firm determines how best to allocate its remaining investment dollars, it will consider the potential return of some portion of those tax dollars if it makes DSM investments. This will introduce a price distortion that biases the firm’s perceived return on investment and leads to inefficient investment choices.14 As a consequence, the firm’s overall operating efficiency will be reduced, as will its overall competitiveness. C. Adverse Economic Impacts of Higher Electric Rates Because the EU charge is a tax on electric rates, increasing the EU budget (and the per kWh tax) will raise the marginal cost of additional electric use and automatically imposes a “drag” on business expansion decisions. There is a standard result from economics that taxing intermediate goods in the production process, such as electricity, reduces economic wellbeing.15 As a result, Vermont businesses contemplating expansion, with all of the concomitant economic benefits, will be less likely to do so when faced with a higher EU tax and more likely to relocate elsewhere, just as they would be less likely to expand in Vermont if the state raises other taxes. Simply put, rates matter, not just bills. Table 1 compares average electric rates in Vermont by sector to average rates in the U.S. as a whole for the years 2003 – 2005. As the table shows, average electric rates in Vermont are significantly greater than the nation as a whole, ranging from 30 percent in the commercial 14 Only if the EU tax paid by the business is exactly what the business would have spent on energy efficiency investments will there be no price distortion. The likelihood of this happening is small. 15 For a survey of the literature on taxation, see V. V. Chari and Patrick J. Kehoe, “Optimal Fiscal and Monetary Policy,” Research Department Staff Report 251, Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis, 1998, p. 21. 6 sector to 45 percent in the industrial sector. significant cost on the Vermont economy. These rate disparities already impose a Moreover, with a number of utilities filing for rate increases, including Burlington Electric, Vermont Electric Cooperative and, most recently, Green Mountain Power, the competitive pressures on Vermont businesses because of high electric rates will only increase. Moreover, according to the DPS’s own analysis, increasing the EU budget will lead to immediate rate increases. By 2009, the DPS estimates rates will be seven percent higher with the EU budget increases than if the current budget is maintained. By 2015, the rate increase will be almost 11 percent higher. These rate increases will impose a significant economic cost on all Vermont businesses. Furthermore, they will increase the distortion between the relative costs of doing business in Vermont and doing business elsewhere. Table 1: Comparison of Retail Electric Rates, Vermont and U.S. Average (Cents per kWh) Year 2003 U.S. Vermont Difference (Pct) 2004 U.S. Vermont Difference (Pct) 2005 U.S. Vermont Difference (Pct) Residential Commercial Industrial 8.70 12.82 47% 8.00 11.29 41% 5.12 8.05 57% 8.97 12.94 44% 8.16 11.42 40% 5.27 7.96 51% 9.42 13.06 39% 8.68 11.35 31% 5.57 8.08 45% Source: USDOE/EIA, Electric Power Monthly, March 2006, Tables 5.3 and 5.6b; Electric Power Monthly, March 2005, Table 5.6b. Under the principle of “Ramsey pricing,” which has long been established in the public finance literature, the most price-sensitive consumers – in this case Vermont businesses – should not be heavily taxed, because doing so leads to greater losses in economic welfare than taxing less price-sensitive consumers.16 This means that, if a uniform tax (such as a per16 See, e.g., F. P. Ramsey, “A Contribution to the Theory of Taxation,” Economic Journal, Vol. 37, No. 145 (March 1927), p.59: “If several commodities which are independent for demand require precisely the same resources for their production, that should be taxed most for which the elasticity of demand is least.” 7 kWh tax on electric rates) is levied on two disparate groups of consumers, the most pricesensitive group will create a disproportional economic loss compared to the less pricesensitive group. Empirical studies of electric consumption nationwide have found that commercial and industrial customers generally have a larger price elasticity of demand than residential customers, and will therefore create greater economic losses to the Vermont economy. One rational economic response by businesses to higher taxes will be to reduce in-state production and/or relocate their operations out-of-state, further damaging the Vermont economy. This, in fact, raises a fourth economic factor that must be considered: the availability of energy efficiency improvements outside the state. D. The Ability to Capture Energy Efficiency Improvements Outside Vermont Firms do not have to be located in Vermont to improve their energy efficiency and their competitiveness. A firm contemplating expansion in Vermont or relocation out-of-state will determine the most “efficient” solution by examining the relative costs it faces for land, labor, and materials, including energy. If it is “more efficient” to do business outside of Vermont, firms will expand or relocate elsewhere. Moreover, just because a firm leaves Vermont does not mean it cannot invest in the same energy efficiency measures elsewhere. Given the “opt-in” provisions of Vermont’s approach to energy efficiency and the requirement that the Board balance other objectives besides capturing the most valuable energy savings, firms’ decisions will be biased towards not expanding in Vermont and/or relocating outside of Vermont. Worse, the bias will be greatest for the most efficient and competitive firms, which will have the fewest opportunities for low-cost energy efficiency investments. In effect, increasing the EU budget is most likely to reward the least energy efficient firms, who are least likely to survive the rigor of the competitive marketplace. And, given the tenuous state of the Vermont economy, this should not be a policy goal. For some firms, especially those that are the least energy efficient, the economic benefits stemming from reduction in their energy bills will be greater than the economic costs of higher electric rates. However, all of the firms that pay more in EU taxes than they receive back from the EU will suffer economic harm. And, again, the most energy efficient firms are likely to suffer the greatest economic losses from EU budget increases, precisely because they have fewer opportunities for additional, least-cost energy efficiency improvements and will thus be most adversely affected by higher EU charges on their electric rates. 3. Measuring the Economic Benefits of Lower Energy Bills Earlier drafts of the Technical Potential Study quoted from a study that estimated 46 new full-time jobs created per million dollars of spending on energy efficiency measures.17 There 17 State of Wisconsin Department of Administration Division of Energy, Focus on Energy Public Benefits Statewide Evaluation, Quarterly Summary Report: Contract Year 2, Second 8 are a number of technical problems with this study, as well as a more fundamental policy problem raised by appealing to such studies to justify economic benefits of increased spending on energy efficiency. One major problem with this study is that it fails to adequately account for the source of the investment funds and, therefore, misses the costs imposed by raising those funds. To understand this, suppose the Federal government sent a check to every Vermonter for $100, increasing total discretionary income in the state by some $65 million. In essence, this income simply arrives out of thin air. Some of that money would be spent in Vermont, some would “leak” outside the state as a result of additional imports, and some would be saved. Many economic impact models are available to estimate these types of impacts and most develop “multipliers” that account for all of the impacts of the increased spending. Next, suppose that the $65 million is distributed to every Vermonter in the exact same way, except now the money has been raised by an equivalent increase in the state income tax. In this case, the economic impacts are likely to be negative because higher taxes have been imposed and used to transfer money between different groups. (Economists call these, not surprisingly, “transfer payments”). Tracing the net economic impacts of such a tax increase is much more difficult, because those impacts will depend on who are the primary payers of the additional $65 million and who are the primary payees, all this without incorporating the administrative costs necessary to implement the program itself—a clear economic loss. In a similar manner, because increasing the EU budget is a tax on Vermonters, the economic impacts associated with the funds collected should be considered transfer payments. Calculating the overall economic impacts of such transfer payments would require a detailed study that accurately followed the dollar flows from residences and businesses to other residents and businesses. Certainly, some firms would benefit, especially those whose business was installing energy efficiency measures. However, many other firms would be adversely affected. The overall impacts of tax increases that simply transfer money between different groups will be negative. Therefore, the prospect of creating 46 full-time jobs per million dollars of DSM spending in Vermont, which would translate into another 800 fulltime jobs if the EU budget were doubled, is not realistic. Finally, from a policy perspective, there is a significant difference between economic benefits and economic impacts. This is an especially crucial difference given the use of the so-called “societal” test to evaluate cost-effectiveness. Under the societal test, economic “benefits” accruing to Vermont from (say) reduced energy imports must be offset by economic “losses” accruing to exporting firms. Ultimately, economic impacts are secondary to investment efficiency. Just as the State does not build schools in order to create new jobs for school bus drivers, increases in the EU budget should be justified on other grounds — Quarter, March 31, 2003, Evaluation Contractor: PA Government Services Inc. Prepared by: Focus Evaluation Team. 9 and as this paper makes clear we do not find economically efficient grounds for an increase — rather than on the basis of a presumed ability to create new jobs. 4. Funds Collected for the EU are not Used in an Economically Efficient Manner The Commenting Parties believe an important question surrounding a higher EU budget is whether the additional funds will be collected and allocated in the most economically efficient manner. This is not meant as a criticism of Efficiency Vermont, which clearly must operate under the guidelines established for it by the Legislature. Nor is it meant as a criticism of the Board, which must balance the three objectives established by the Legislature in Act 61. One of the basic premises underlying the formation of the EU was that businesses and individual consumers either could not, or would not, respond to market signals “efficiently.” In other words, they won’t make the “correct” economic decisions. This has been attributed to lack of information, market barriers, and even consumer “irrationality.” The Commenting Parties disagree that an increase is needed in the EEU budget to fully prompt good market-based decision making. As an example, the rapid increases in the price of gasoline last year as a result of Hurricanes Katrina and Rita showed that, in fact, consumers do respond to market signals, and respond quickly. Sales of gas-guzzling SUVs plummeted, and consumers sought out other ways to reduce their gasoline consumption. And, as noted previously, businesses have a tremendous market incentive to improve their overall operational efficiency, including their use of energy, so they can remain competitive and profitable. Thus, we believe energy efficiency savings can be captured at a lower cost when businesses and individuals make their own, market-based decisions about energy efficiency ─ be it purchasing a hybrid car, a frontloading washing machine, or compact fluorescent bulbs ─ rather than levying what effectively will be higher taxes on businesses, creating an administrative burden to collect those taxes, and using them to fund programs that subsidize energy efficiency investments for selected groups. A. Market Barriers to Improved Energy Efficiency One of the original reasons for creating the EU was the assertion that market barriers prevented the widespread adoption of energy efficiency measures. One of those barriers was the high initial cost of energy efficiency measures. Although there is no single definition of market barriers, the “classic” operational definition used in economics encompasses any costs that must be borne by firms seeking to enter (or exit) an industry that are not borne by incumbent firms. 18 18 See, Stigler, G. (1968), The Organization of Industry, Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press. 10 The fact that the price of a good or service is higher than a similar one is not evidence of barriers to entry. Instead, a high market price can be indicative of a different demand and supply structure. For example, the price of a Rolls Royce is much higher than the price of an average automobile. But this does not mean that Rolls Royce faces market barriers in the automobile market, even if most people cannot afford to buy one. Similarly, the fact that front-loading washing machines sell for higher prices than typical top-loading ones does not mean manufacturers of front-loading washing machines face market barriers. The validity of barriers to entry arguments preventing more widespread adoption of energy efficiency measures is questionable. While there may be informational barriers that can be addressed by the EU, addressing price barriers through rebate programs and subsidies, which are a major component of Vermont’s approach to energy efficiency spending, is not addressing a legitimate market barrier. Indeed, presuming that information barriers are overcome, consumers will not need any other incentives to invest in cost-effective energy efficiency, since they will know how beneficial such investments are. B. Inefficiency Created by the Discrepancy Between Avoided Costs and Rates The Technical Potential Study uses a forecast of wholesale electric market prices in New England, plus estimates of avoided transmission and distribution (“T&D” costs) and externalities, as the basis for the avoided costs used to determine the cost-effectiveness of energy efficiency programs. But “opt-in” decisions made by businesses and individual consumers will be based on their personal “avoided costs,” in other words their retail rates. This price distortion reduces economic benefits and increases the overall costs to obtain energy savings. As long as retail rates differ from the avoided cost estimate, the optimal level of DSM investment will not occur. Consumers will either “opt-in” too much or not opt-in enough.19 Moreover, to the extent that consumers’ retail rates reflect fixed and variable costs, then non-participants will be harmed disproportionately compared with program participants. Since the largest business and industrial customers tend to have the lowest retail rates, they will tend to “opt-in” to EU programs less than residential consumers, who pay higher retail rates. Thus, business consumers will end up subsidizing residential customers, much as electric utility customers who participate in net-billing arrangements are subsidized by nonparticipants. Those subsidies will further exacerbate the adverse economic impacts on Vermont businesses. Now, it is possible that energy efficiency investments will slightly reduce wholesale electric prices, i.e. avoided costs, in Vermont. (However, even if one were to accept the Technical Potential Study’s forecast annual energy savings if all cost-effective energy efficiency is captured – and we believe those energy savings are significantly overstated, the magnitude of those savings is less than one percent of the forecast energy sales in New England as a 19 This presumes the entire avoided cost approach and identification of all cost-effective energy savings is correct, which, as discussed in Section V, it is not. 11 whole.20) The amount of such price decreases, if any, will depend on the magnitude and type of energy efficiency measures targeted, and the price elasticity of demand. For example, energy efficiency investments that reduce peak loads may help reduce peak-hour price spikes.21 Lower wholesale prices would eventually benefit Vermont businesses. However, because all of Vermont’s electric utilities are fully regulated, they will only benefit to the extent that energy efficiency investments lead to lower retail rate increases than they otherwise would, or defer future retail rate increases. Therefore, energy efficiency investments will provide neither contemporaneous rate relief nor economic benefits, because retail rates are fixed and utilities do not file for new rates whenever there is a change in wholesale electric prices. 22 Thus, while the adverse economic costs of higher EU taxes will be felt immediately, any economic benefits from lower wholesale market prices and lower retail rates will be deferred. This will further reduce the economic value of those benefits compared to other investments in operational efficiency businesses can undertake immediately on their own. Moreover, wholesale price decreases, if any, are likely to be far outweighed by retail rate increases, based on the DPS’s rate impact analysis. Additionally, the “benefits” of lower electric prices cannot be counted in the societal test framework used in the Technical Potential Study. The reason is that market price decreases are simply a transfer payment from suppliers to consumers.23 Furthermore, to the extent that DSM investments lower wholesale rates in New England as a whole, investments paid for by Vermont businesses and individuals will subsidize the rest of New England. Ironically, for businesses in Vermont, this means that a higher EU budget may force them to subsidize their direct competitors. C. The Efficiency of the Marketplace Economists agree that allowing consumers, especially businesses, to make their own energy efficiency decisions is more efficient than using government programs, because markets are 20 Appendix D of the Technical Potential Study estimates annual energy savings of about 1300 GWh, less than one percent of the estimated total New England energy sales of over 151,000 GWh in 2015, as published in the April 2006 ISO-NE Report, “2006- 2015 Forecast of Capacity Energy Loads and Transmission” (“CELT Report”). The average wholesale price change from such a reduction in demand is likely to be quite small. 21 Peak load reductions will also reduce Vermont utilities’ capability reserve requirements, and thus their locational installed capacity payments. 22 Even under a so-called “alternative regulation” framework that provides for automatic power cost adjustments (“power cost adjustment clause”), rate changes would not be a daily occurrence. Instead, power cost adjustments are more likely to occur periodically. 23 In technical terms, increased spending on energy efficiency that leads to lower wholesale rates is what economists refer to as a “pecuniary externality.” 12 the most efficient allocators of scarce resources. It avoids unnecessary administrative costs associated with collecting and distributing funds, avoids having to address multiple, competing objectives that increase the cost of achieving cost-effective energy savings, and, most importantly for firms, allows firms to determine for themselves their most efficient capital investment strategies for improving overall operating efficiency and competitiveness. The Commenting Parties contend that the distribution of EU funds collected is not efficient and, in particular, penalizes businesses. Indeed, the language of Act 61 requiring the Board to balance three different, and competing, objectives strongly suggests that the distribution of the EU funds is less efficient than the market. But it makes no economic sense to establish a budget amount before determining those weighting factors – it is those factors that drive the overall cost-effectiveness of the funds spent by the EU. Since the inception of the EU, Vermont businesses have been most affected by the inefficiency of fund distribution and allocation, paying in more to the EU than they have received in payments for energy efficiency investments. This hardly seems an appropriate way to encourage greater energy efficiency among Vermont’s businesses. Moreover, increasing the EU budget and therefore the effective tax on electric rates paid by electric intensive industries will imposes additional economic costs on the Vermont economy: goods and services that require relatively more electricity as an input will become more expensive relative to the same goods produced in other states, as well as goods that require less electricity in their production. Commercial and industrial customers have more energy choices than residential customers and should be allowed to make their own energy efficiency decisions, based on market forces. The Commenting Parties believe there are many ways to improve energy efficiency and that Vermont businesses should not be treated as a single class like the Residential sector. Simply put, we believe there needs to be more emphasis on market-based alternatives, rather than increasing the EU budget, to deliver additional energy efficiency at a lower cost while meeting the objectives set out by the Legislature. For example, there are many firms that offer “shared-savings” arrangements and performance contracts. These could be offered by the EU, other vendors, or through other policies. Revolving credit arrangements are another alternative. A third is voluntary EU membership, in which businesses who most need information and assistance could sign-up with the EU, while those who had their own, internal expertise would be able to “opt-out.” No doubt there are many other alternatives as well. The Board should thoroughly explore these and other alternatives before increasing the EU budget. 5. Modeling Flaws in the Technical Potential Study The Technical Potential Study sets out to identify all “cost-effective” energy savings and the budget necessary to capture those savings. But in balancing the three objectives set out by the Legislature, however, the Board should be cognizant of the fundamental difference between what is “cost-effective” and what is “least-cost.” This is especially important in 13 light of the third legislative objective: capturing energy efficiency savings where they have the greatest value. A. Cost-Effectiveness vs. Least-Cost The discrepancy between cost-effectiveness and least-cost arises because capturing all costeffective efficiency investments cannot, by definition, be a “least-cost” strategy. The reason is that the cost-effectiveness argument used in the Study to justify the EU budget increase is an average cost concept, while “least-cost” is a marginal cost one. The two are not the same. To determine whether a given efficiency measure is cost-effective, the GDS study compares the present value of the energy savings of the measure, based on the forecast price of electricity and the expected energy savings the measure will provide, against the expected cost of the measure. If the total cost of purchasing and installing the measure is no greater than the present value of the energy savings over the measure’s anticipated lifetime, that measure is deemed cost-effective. For example, a compact fluorescent (“CF”) bulb costing five dollars more than the incandescent bulbs it replaces (because the CF is supposed to last longer) will be cost-effective as long as the present value of the electric savings it provides over time is at least five dollars. In designing a residential lighting program, it’s not possible to evaluate the cost-effectiveness of every single CF that could conceivably be installed. Instead, the typical approach, which is the approach used by GDS, is to estimate the total number of incandescent bulbs that might be conceivably replaced (technical potential), then reduce that number to reflect how many bulbs might actually be replaced even with unlimited resources (maximum achievable potential), and then finally determine the total number of replacements that are costeffective (maximum achievable cost-effective potential). The maximum achievable costeffective potential would be determined by, in essence, constructing a CF supply curve and then moving along that supply curve until reaching a point where the total replacement cost just equals the net present value of the energy saved. Put another way, the maximum achievable cost-effective potential occurs where the average cost of saved energy from the program just equals the average avoided cost. At that point, the marginal cost of replacing some specific CFs will therefore be greater than the average cost. (Unless the average cost of replacing each and every CF is exactly the same, meaning the average cost equals the marginal cost, then the cost of some CF replacements will be less than average cost and others will be more than the average cost.) The net energy expenditure savings, if the maximum achievable cost-effective potential is captured, compared with a status quo case of no program, are zero. This is because, by definition, the total cost of achieving the savings just offset the NPV savings themselves. In other words, what is cost-effective is not necessarily what is economically efficient. This is the fundamental economic reason why the cost-effectiveness standard used in the Study is wrong: it bases cost-effectiveness on average cost, rather than using marginal cost analysis to determine the least-cost level of efficiency. The latter approach is the correct economic framework. As a result, the entire analysis should be redone to determine the least-cost level 14 of investment, which will necessarily be less. Another example further clarifies this point: suppose a firm faces a lawsuit that would cost it $100 million if no legal efforts were made. The firm can spend $99,900,000 on attorneys and be certain it will win the lawsuit. Such a decision would be cost-effective, because the firm gains $100,000. But it will not necessarily be the least-cost decision. After all, the firm only saves $100,000, while a smaller expenditure in legal counsel might provide it with a high probability of saving the entire $100 million.24 In essence, determining the EU budget necessary to achieve the “full-amount of costeffective energy savings,” as is done in the Technical Potential Study, is the same as asking “how long can we defer investments in new generating capacity with demand side management (“DSM”) investments?” Indeed, this question has been explicitly asked in the distributed utility (“DU”) planning efforts undertaken by the DPS and Vermont utilities under the DU Planning Guidelines. To understand this point more clearly, consider the total cost of supplying electricity, either in the form of generation or DSM savings. The goal is to determine the level of DSM investment that will defer generation investments and yield the lowest present value cost supply of electricity. This is shown in Figure 3. The curve labeled “PV Total Cost” represents the total present value of each combination of deferred generation and DSM that meets customer needs. The curve labeled “PV-DSM Cost” is the present value cost of all of the DSM investments. The curve labeled “PV-Avoided Cost” represents the present value of the avoided (deferred) cost of electricity, including capacity cost savings, T&D, environmental externalities, and so forth. The maximum cost-effective level of DSM investment is shown as DSMC/E, where the present value of the DSM investment just equals the present value of the avoided (deferred) generation costs (Point A). Deferring new generation investment beyond this time has a lower average present value benefit than the average present value cost of additional DSM investment. The level of DSM investment at Point A, while capturing all cost-effective savings, does not result in a least-cost electric supply. Instead, the least-cost generation mix is achieved with an investment of DSM*. This level of DSM occurs where the difference between the “PVDSM” and “PV-Avoided Cost of Energy” curves is largest. It is also the point where the slopes of the two curves, representing the marginal cost of additional DSM and the marginal benefit of deferred generation are equal. Thus, maximum deferral (i.e., acquiring all costeffective DSM) is not the same as least-cost.25 24 Under a marginal cost analysis, the firm would hire additional attorneys until the last dollar spent in legal counsel provides one dollar of expected savings. 25 For a more detailed analysis, see, J. Lesser and C. Feinstein, “Electric Utility Restructuring, Regulation of Distribution Utilities, and the Fallacy of “Avoided Cost” Rules,” Journal of 15 Present Value Cost ($) C/E Deferral "Least-Cost" Deferral A PV Generation Cost PV DSM Cost PV Total Cost Slopes Equal PV Avoided Cost DSM* DSMC/E Deferral time (years) Figure 3: Cost-Effective vs. Least-Cost Deferral Times An Example: Early Appliance Replacement Programs The Technical Potential Study evaluates several different appliance replacement programs (including fuel-switching programs) that replace older, less efficient appliances with newer, more energy efficient ones. To see how the economic benefits and costs of such programs are calculated, and illustrate how those costs and benefits can vary, consider a program that encourages consumers to replace their older refrigerators with new ones. The economic value of this program will depend on the value of the annual electricity savings (based on net kWh savings per year and the price of electricity) and the expected lifetimes of old and new refrigerators. It will also depend on the size of the rebates provided to consumers to induce them to switch. Analyzing the value of replacing a single refrigerator is straightforward: we simply compare the present value of the energy savings26 against the present value cost of buying a new Regulatory Economics 15 (1999), at 93-110 (“Lesser and Feinstein 1999”). A copy of this paper is available on request. 26 A complicating factor is technological improvement. Specifically, if refrigerators in the future are expected to be even more energy efficient, encouraging consumers to replace today will, all other things equal, reduce the benefits of early replacement. 16 refrigerator before the old one wears out. (For simplicity, it’s easiest to assume that the consumer will purchase the energy efficient refrigerator when the old one wears out. Thus, there are no incremental energy savings beyond the expected time when the old refrigerator will be replaced.) Assume that a new refrigerator has an expected lifetime of 20 years, that an old refrigerator is currently 10 years old (and therefore has an expected remaining life of 10 years), and that the price of electricity is $100/MWh ($0.10/kWh).27 We also assume that the old refrigerator uses 800 kWh/year, while the new one uses only 200 kWh/year. We also assume there is no rebate offered. Finally, we assume an inflation rate of 2.5 percent and a real discount rate of 2.3 percent. The NPV of early replacement in a given year (prior to year 10, when the old refrigerator is assumed to wear out), is shown in Figure 4. NPV Savings of Early Equipment Replacement $15.00 $10.00 $5.00 $0.00 ($5.00) ($10.00) ($15.00) 0 2 4 6 8 10 12 14 16 18 20 Early Replacem ent in Year T Figure 4: NPV Early Replacement – Consumer Perspective As Figure 4 shows, from an individual consumer’s standpoint, it is cost-effective for the consumer to switch as early as year 2, when the NPV first becomes positive. However, the most economically efficient time to replace the old refrigerator, i.e. the least-cost replacement policy, is when the NPV is at a maximum. That does not occur until year 6, when the NPV is just over $11. Suppose, however, the consumer is offered a $50 rebate. In that case, it is cost-effective for the consumer to switch immediately, even though the best year to switch is year 3, as shown on in Figure 5. But if the consumer has a higher real 27 To simplify the example, we assume that the retail rate paid by the consumer is the same as the wholesale avoided cost. To the extent that per kWh retail rates include some fraction of a utility’s fixed costs, the disparity between the optimal replacement decision from the consumer’s standpoint and the optimal replacement decision from society’s standpoint will diverge further. 17 discount rate, say 3.5 percent, early replacement is not cost-effective until year 5, and not value maximizing until year 7, as shown in Figure 6. NPV Savings of Early Equipment Replacement $30.00 $25.00 $20.00 $15.00 $10.00 $5.00 $0.00 0 2 4 6 8 10 12 14 16 18 20 Early Replacem ent in Year T Figure 5: NPV Early Replacement – with Rebate NPV Savings of Early Equipment Replacement $10.00 $5.00 $0.00 ($5.00) ($10.00) ($15.00) ($20.00) ($25.00) ($30.00) ($35.00) 0 2 4 6 8 10 12 14 16 18 20 Early Replacem ent in Year T Figure 6: NPV Early Replacement – Higher Discount Rate This example further illustrates another program issue, which stems from the dichotomy between societal benefits and benefits to the individual consumer. This is shown in Figure 7. From society’s perspective, it is cost-effective to replace the old refrigerator immediately, but most valuable to replace it in year 5. However, from the consumer’s standpoint, if there 18 is no rebate, it is never worthwhile to replace the old refrigerator. It turns out that a rebate of $120 is necessary to align the optimal replacement year for consumers and society, also in year 5. NPV Savings of Early Equipment Replacement $40.00 $20.00 $0.00 ($20.00) Consumer ($40.00) Society ($60.00) ($80.00) ($100.00) ($120.00) 0 2 4 6 8 10 12 14 16 18 20 Early Replacem ent in Year T Figure 7: NPV Early Replacement – Consumer and Society Finally, the societal analysis also assumes, crucially, that the rebate, which is funded by the EU tax, has no negative impact on overall economic welfare. However, as discussed previously in Section III, levying taxes, especially on intermediate goods like electricity, will have adverse impacts on welfare, unless the tax exactly equals the external costs of producing the intermediate good. B. Flaws in the Technical Potential Study’s Avoided Cost Models The Commenting parties have not had sufficient time to properly evaluate the avoided cost spreadsheet models used to determine the level of cost-effective energy savings. We were provided with the models on April 25, 2006, allowing only one week for review. The very large size of these spreadsheet models makes a comprehensive evaluation of the results difficult, as many modeling assumptions and formulae must be traced and evaluated for their accuracy. We request that the Board provide additional time to allow for a complete evaluation of these models. In our brief review of the models, however, we have encountered three potential problems and inconsistencies. The first is a discrepancy between the discount rate used to develop levelized avoided costs and the discount rate used to determine the NPV and costeffectiveness of program measures. Specifically, the avoided energy supply costs (“AESC”) used in the spreadsheet models were estimated using a model developed by ICF 19 Corporation. ICF used a real discount rate of 2.03% to levelize those avoided costs. 28 However, in the spreadsheet “GDS Vermont Model-Light Mfg-existing.xls,” the worksheet entitled “Input” the assumed real discount rate is 5.60%. We are not aware of a societal analysis that uses one (societal) discount rate to calculate levelized avoided costs and another discount rate to estimate net present value savings. A second concern we have is the use of energy “loss multipliers” ranging between 15 percent and 24 percent. It appears that energy efficiency measures are credited with additional 15 – 24 percent in savings, presumably to address system losses. The source of these loss multipliers is shown to be “Dave Lamont VDPS.” The Commenting Parties are concerned that these loss multipliers are far too high and that there is no documentation as to how they have been estimated. A third concern is the assumed value for avoided T&D costs. The same spreadsheet model uses a value of $162.75/kW-year. We question the validity of this avoided cost figure, which appears to account for a significant portion of the total NPV benefits of some efficiency programs. For example, in the same spreadsheet, avoided T&D costs account for over 40 percent of the total NPV benefits for Program P1. The problem with the T&D “avoided cost” assumption has been well-documented by Dr. Lesser in several peer-reviewed publications,29 as well as in testimony he provided in Docket No. 6860 on behalf of the DPS. Together with the assumed energy loss multipliers, it appears that energy efficiency measures are being credited with an additional 60 percent in value on top of their expected energy savings. Given these three modeling issues, which we found in a brief review of the accompanying spreadsheets to the Technical Potential Study, we are concerned there may be other inconsistencies and problematic assumptions. We strongly urge the Board to delay the schedule so as to allow us sufficient time to investigate these models thoroughly and for all parties to understand these issues. C. The Failure to Address Uncertainty In a brief section on “Fairness and Equity Issues,” the Technical Potential Study discusses uncertainty over program savings and costs. The Study states that,“[d]espite the considerable experience with programs, savings estimates always require some degree of understanding of what would have happened but for the existence of the program. This is not simply a question of engineering calculations or metering, but of judgment for which reasonable persons may differ and certainty is never assured.”30 This is true. However, the 28 See the spreadsheet file “aescpoweravoidedcostsexhibits2002.xls,” worksheet “Exhibit 12005$,” Note 3. 29 See, e.g., Lesser and Feinstein (1999), op. cit. 30 Technical Potential Study, at 84. 20 Study authors fail to understand that the correct economic approach to addressing uncertainty is not to assume it away, as they have done. Moreover, there is another important uncertainty the Study’s authors fail to mention: uncertainty over future electric and fossil fuel prices, whose volatility has increased substantially over the last few years The avoided cost approach, whether embodied in a societal test, total resource test, or any other test, has never correctly addressed the treatment of uncertainty. In fact, the Study does not deal with uncertainty at all, other than to say, “certainty can never be guaranteed.” By ignoring the issue and relying solely on point forecasts, the results of the analysis are wrong, because the probability that all of the assumptions they have employed are correct is zero. Since they are a point forecast, by definition, we know that those forecasts will be wrong. Moreover, the effects of uncertainty cannot be addressed simply through sensitivity or scenario analysis. The problem is that the optimal investment solution when uncertainty is present, in this case the level of energy efficiency investment, will not equal the level of investment determined when using a point forecast. For example, suppose we think the price of electricity will vary between $50/MWh and $100/MWh, with an average value of $75/MWh. Using the $75/MWh value as the avoided cost, we determine that the least-cost level of energy efficiency investment should be 100 units. If we specifically address uncertainty in the cost of electricity to determine the number of energy efficiency units that should be purchased, the answer will be less than 100 units. This is because risky investments are less valuable than safer investments that provide the same average outcome—a result that stems from basic financial principles.31 When there are multiple uncertainties, such as measure lifetime, savings per measure, electric and fossil fuel prices, even changes in regulation, such as the evolving locational installed capacity market (“LICAP”) in New England, it becomes even more important to address those uncertainties explicitly to determine a truly least-cost solution. Fortunately, there are well-established methods to address uncertainty, such as using dynamic programming methods, such as decision tree analysis. In fact, just such an approach was used in testimony Dr. Lesser submitted on behalf of the DPS in Docket No. 6860 to determine whether the Northwest Reliability Project could be deferred by DSM investments. This surfeit of mechanical flaws – the failure to address uncertainty and the failure to provide any empirical basis for many of the underlying assumptions – is disturbing because the adverse economic impacts on Vermont businesses from analytical errors will be quite real. This is not a risk Vermont businesses can absorb, given the already difficult economic conditions under which they must struggle. 31 For additional discussion, see, Electric Power Research Institute, Utility Capital Budgeting Notebook, Final Report, TR-104369, July 1994, Chapter 12. 21 D. Erroneous Non-Economic Benefits Estimates The Technical Potential Study also contains a discussion about the numerous “noneconomic” benefits of increased investments in energy efficiency.32 The Study lists environmental benefits, improved reliability, greater comfort, improved competitiveness, and the creation of new jobs, among others. Not only are these non-economic benefits unsubstantiated, most are at odds with the societal test framework used in the Study. Specifically, the authors confuse impacts with benefits. Consider environmental benefits. The Technical Potential Study includes environmental externality values established by the Board. Those benefits stem from avoided emissions of SO2, NOx, and greenhouse gases. The problem with this is that SO2 and NOx emissions are already capped under the Clean Air Act. Additional energy efficiency investments do not change that cap. Instead, the net effect will be a slight reduction in the market clearing prices of emissions allowances, but no change whatsoever in total emissions levels. In other words, businesses outside Vermont would purchase emission allowances at a discount – financed at the expense of Vermont businesses and ratepayers. As for reductions in carbon dioxide emissions, the benefits of such reductions, if any, will be distributed worldwide, and the fraction of benefits accruing to Vermonters will be de minimus. Thus, Vermont businesses will absorb 100 percent of the costs, in the form of higher electricity rates, while enjoying almost none of the benefits. Instead, customers elsewhere in New England will free-ride on Vermont’s actions. Regarding reliability benefits, it appears that the authors equate reliability with fuel supply adequacy and price volatility. While those are important issues, the effects of DSM investments on them will be negligible. Moreover, in testimony before the Board in Docket No. 6860, proponents of using energy efficiency investments to defer or obviate the need for the Northwest Reliability Project made similar arguments. However, witnesses for ISONE strongly disagreed with their arguments, because energy efficiency investments cannot be controlled by the ISO. The problem is that, since energy efficiency measures are on the customer side of the meter, there is no way to know whether those measures are actually saving as much energy, at the necessary times, as predicted by modeling exercises. That uncertainty poses a significant reliability risk. Moreover, the Study fails to account for differences in the value of efficiency measures that reduce peak loads and those that do not. Yet, this is an important consideration, for several reasons. First, the value of peak energy savings is greater than off-peak energy savings. Second, and more importantly, reductions in peak loads will reduce Vermont utilities’ capability reserve requirements under Standard Market Design (“SMD”) and thus their required LICAP payments. 32 Technical Potential Study, at 81-84. 22 6. Conclusions and Recommendations The Commenting Parties recognize the benefits of improved operating efficiency, including improved energy efficiency. Having to compete in a global economy, the individual businesses represented by the Commenting Parties are well aware of the need to seek out efficiencies continually. It is for this overarching reason that the Commenting Parties oppose any budget increase for the EU. First, in contrast to the conclusions made in the Technical Potential Study, increasing the EU budget will disproportionately harm Vermont businesses, not help them. Vermont already has the highest per capita tax burden of all 50 states. Additional increases in this tax burden will further disadvantage Vermont businesses, which already labor in a high tax, high cost environment. Second, electric rates matter as much, or more than, bills. Rates are a critical factor in the decisions made by Vermont businesses to expand operations in state and create new employment opportunities, or to expand outside the state and send jobs elsewhere. Third, markets are far more efficient allocators of scarce economic resources than are governments. Yet, because of the multiple, and competing, objectives that must be satisfied under 30 V.S.A. § 209(d), the EU budgeting process cannot be as efficient as the market. We believe there are alternatives to increasing the EU budget and raising rates for business customers, and we urge the Board to explore such alternatives. Fourth, the mechanical aspects of the Technical Potential Study, which form the basis for recommendations to increase the EU budget, suffer from significant methodological flaws. By basing budget estimates on a cost-effectiveness standard, the Study has failed to identify a least-cost solution. Moreover, the avoided cost approach used to identify maximum achievable cost-effective savings suffers from numerous flaws. Some of the assumptions used in the Study appear inconsistent and the entire analytical approach fails to account for the very real impacts of market and non-market uncertainties. These inconsistencies need to be examined in more detail. Given the limited time the Commenting Parties have had to review the specific models developed by the authors of the Technical Potential Study, we ask the Board to delay the schedule so as to provide more time for us to review those models. 23