Online Resources for Chapter 05 Chapter 5 Word Document

advertisement

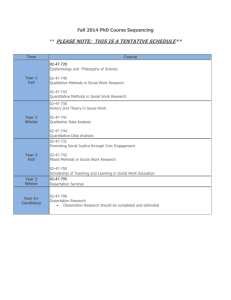

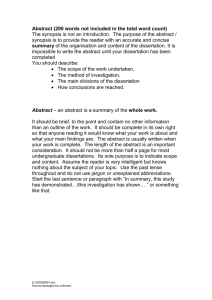

CHAPTER 5: WRITTEN AND ORAL COMMUNICATION. Legal Writing: An Example (page 168). Below is an example of a bad piece of legal writing in an exam. Can you turn it into a good example in the empty box below? See the completed example below. Bad example Good example ‘The drunk man stole some DVDs from the corner shop. He was arrested under theft. He went to court and his excuse was that he was drunk. They said in the court room that the drunk man needed to intend to steal the DVDs. He said he was so drunk he didn’t know what he was doing.’ The defendant dishonestly appropriated some DVD’s from a corner shop. The was arrested under section 1(1) of the Theft Act 1968. He raised the defence of intoxication. The mental requirement for theft is intention or recklessness to permanently deprive. The defendant argued that he was so intoxicated he could not form the required intention. Plagiarism Activity (page 209). Activity: Imagine that the abstract below is published in a popular law journal. You need to use it in your assignment. In the empty box below, the research has been incorporated into a paragraph about how a student may feel about the death penalty in criminal law, but it is not plagiarised. It is referenced properly. A suggested answer is provided below. ‘Research from the state penitentiary in Texas found that defendants on death row live longer than those in the cells for life. Additionally, those on death row have a chance to think about their impending death, and repent for their sins. Two wrongs do not make a right. The victims’ family will never be able to accept their loss anyway – why then kill the perpetrator when it does not bring the victim back?’ Suggested answer: “The death penalty does not provide adequate punishment for murder. It does not bring the victim back. Research has shown that life on death row is not as bleak or as ‘final’ as it seems. Research from Texas found that inmates live for a considerable amount of time on death row, and even seek forgiveness for their sins.* They have the opportunity to come to terms with their punishment, leading to possible calmness and acceptance. *Footnote: Surname, Initial. (Year). ‘Title of Article’. Journal. Volume, page number. Planning and Drafting Coursework (general online materials for Chapter 5). Assignments fail because they are badly written. Good assignment writing is a skill which takes three years to learn through assignment feedback and reading a lot of law books and journals. Materials for this task (six cases and assignment question): Carlill v Carbolic Smoke Ball Company [1893] 1 Q.B. 256, Bowen L.J.: It is an offer made to all the world; and why should not an offer be made to all the world which is to ripen into a contract with anybody who comes forward and performs the condition? It is an offer to become liable to any one who, before it is retracted, performs the condition, and, although the offer is made to the world, the contract is made with that limited portion of the public who come forward and perform the condition on the faith of the advertisement. Fisher v Bell [1961] 1 QB 394, Lord Parker C.J.: The sole question is whether the exhibition of that knife in the window with the ticket constituted an offer for sale within the statute. I confess that I think most lay people and, indeed, I myself when I first read the papers, would be inclined to the view that to say that if a knife was displayed in a window like that with a price attached to it was not offering it for sale was just nonsense. In ordinary language it is there inviting people to buy it, and it is for sale; but any statute must of course be looked at in the light of the general law of the country. I find it quite impossible to say that an exhibition of goods in a shop window is itself an offer for sale. Pharmaceutical Society of Great Britain v Boots the Chemist [1952] 2 Q.B. 795, Lord Goddard: I think that it is a well-established principle that the mere exposure of goods for sale by a shopkeeper indicates to the public that he is willing to treat but does not amount to an offer to sell. In my opinion it comes to no more than that the customer is informed that he may himself pick up an article and bring it to the shopkeeper with a view to buying it, and if, but only if, the shopkeeper then expresses his willingness to sell, the contract for sale is completed. Partridge and Crittenden [1968] 1 W.L.R. 1204 – Ashworth J: The words are the same here “offer for sale,” and in my judgment the law of the country is equally plain as it was in regard to articles in a shop window, namely that the insertion of an advertisement in the form adopted here under the title “Classified Advertisements” is simply an invitation to treat. Byrne v Van Tienhoven (1880) 5 C.P.D. 344 – Lindley J: It appears to me that both legal principles, and practical convenience require that a person who has accepted an offer not known to him to have been revoked, shall be in a position safely to act upon the footing that the offer and acceptance constitute a contract binding on both parties. Felthouse v Bindley (1862) 11 CBNS 869; 142 ER 1037 – Silence is not acceptance. Assignment question: ‘Discuss when an ‘offer’ is not an offer for the purposes of contract law.’ Task 1: Write a small and very basic introduction to this assignment - about 5 or 6 lines will do. This should outline what your assignment will look at. There is no need to go into detail about cases at this point, but the reader will appreciate an overview of the area of law you are about to discuss. Task 2: Write the first paragraph for your assignment. About 10 or 12 lines should do. Here is some basic structure guidance for your opening paragraph: Open your topic: what is an offer in contract law? How are they formed? Any key principles? Describe the case authorities one at a time Remember, each case will attract marks (as long as it’s used appropriately). This is where cases and legal principles are introduced to the reader. Task 3: Listed below are ‘high order’ skills to put into an assignment or exam (becoming more important as they go down the list): 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. 6. Knowledge (describe, define) Comprehension (explain) Application (apply, demonstrate) Analysis (assess, consider) Synthesis (justify, compare, contrast, distinguish) Evaluation (criticise, evaluate, comment, reflect, discuss) Now write a second paragraph of about ten lines, containing the following information for the reader: Comment on whether the authorities are satisfactory and/or logical; A critical analysis of the law; Apply the authorities to the question (application); An evaluation of the law. You should notice that your assignment answer is forming a particular structure: the introduction opens the area of law to the reader, the first paragraph introduces theories and cases, the main paragraph applies, criticises and evaluates those theories and cases, and a conclusion draws it all together. Task 4: Don’t forget your conclusion! Evaluate your evidence, bring everything together, and revert back to your original point in your introduction so there is a thread running through the whole piece. Plagiarism Self-Assessment (general online materials for Chapter 5). Fill in the table below. Which examples do you think need referencing? Work You include tables, photos, statistics and diagrams in your assignment from a book or an article. When describing or discussing a theory, model or practice associated with a particular writer. You summarise information drawn from a variety of sources about what has happened over a period of time. Views from other academics or judges to give weight or credibility to your argument. When using others’ views to give emphasis to a particular idea of yours. When pulling together a range of key ideas that you introduced and referenced earlier in the assignment. When stating or summarising obvious facts and when there is unlikely to be any significant disagreement with your statements or summaries. When using quotations in your assignment. If you copy and paste items from the Internet where no author’s name is shown. When paraphrasing or summarising (in your own words) another person’s idea that you feel is particularly significant or likely to be a subject of debate. Legal Language (general online materials for Chapter 5). Yes No In the table below, distinguish one word from another by writing a single sentence explaining what each word means. Word: Their Meaning: There Should have Should of Principal Principle Advise Advice Practice it Their practice Cause of action Course of action Precedence Precedent Affect Effect Comma Activity (general online materials for Chapter 5). In the box below, place the commas where you think they should go: “The policeman said that the old woman saw the burglar in the shop where she was that afternoon. The policeman also said that the burglar who was in the shop stole the contents of the shop when the shopkeeper was not looking thinking that the camera was off. When the girl who was outside walked into the shop she tripped over the burglars bag and that is how he became distracted. Unfortunately the old lady who was a witness from the beginning was in the line of fire but the shot missed her. She is shaken up but she provided an excellent statement which is being reviewed by the police today as we speak. The girl who disturbed the burglar recognised his voice remembering her boyfriend’s own and is also a valuable witness. The shopkeeper was hiding behind the counter.” Hopefully, it should be clearer now, how important commas are to your legal arguments. If you do some critical thinking in your essays (which you should!) then you will need the odd comma in your sentence to stop for breath while you argue your point. Legal sentences can sometimes be quite long, and so commas are particularly useful in a subject like law. Apostrophe Guidance (general online material for Chapter 5). The apostrophe is used in the following situations: 1. To show where a letters have been left out and two words have been merged together: It is Two words: “It is” “You will” “He is” It s It’s Merged with an apostrophe: “It’s” “You’ll” “He’s” “Do not” 2006 “Don’t” ‘06 Using an apostrophe in these situations is acceptable for informal pieces of work or making notes, but this ‘shorthand’ should be avoided in formal writing for assessment purposes on your law courses. The law lords do not do it in their law reports, because it is seen as a ‘short cut’ to writing properly. 2. To indicate possession: This is when the apostrophe shows ownership or possession of something: Long sentence: The University has a Charter Every University shares a Charter The course has some aims The outcomes of the module The system is complex The rights of women Shortened with an apostrophe: The University’s Charter The Universities’ Charter The course’s aims The module’s outcomes The system’s complexity Woman’s rights Plural Guidance (general online material for Chapter 5). Plural Problems A ‘plural’ means ‘more than one’. Apostrophes are almost never used with plurals: Plural: “Taxis only” “CDs, videos, books and gifts” “Desserts” “CVs” “Assignments” “Strategies” Wrong use of an apostrophe: Taxi’s only CD’s, video’s, book’s and gift’s Dessert’s CV’s Assignment’s Strategy’s Analysing your Assignment Title (general online materials for Chapter 5). It is paramount that the student understands fully the assignment question before attempting to answer it. Experience from practice has demonstrated that many students do not fully understand the assignment questions. This has the effect that the answers given are not fully relevant to the questions or are not relevant at all! Below are other examples of assignment questions: Contract law: “Describe the laws relating to the formation of a contract, and analyse their effectiveness.” Legal skills: “Reflect on your own presentation skills and draw up an action plan of how you would like to improve during your degree.” European law: “Critically analyse the laws regarding the free movement of persons within the European Union. Do you think they are adequate?” Criminal law: “Identify the instances in which a defendant can use the defence of intoxication and evaluate the current limits of the defence.” Notice the following hints in the questions: Subject: Contract law Legal skills European law Criminal law Topic to research: Formation of a contract Presentation skills & action plan Free movement of persons in the EU The defence of intoxication Skills to illustrate: Description & analysis Reflection & planning Critical analysis & evaluation Identification & evaluation Sometimes especially when dealing with long or complex questions it may be useful to break down the assignment question into a number of sub-questions (or sub-topics) each covering a key issue that you need to discuss. Example: “Parliament has under the English Constitution the right to make or unmake any law whatever. No person or body is recognised by the Law of England as having the right to set aside the legislation of parliament”. Explain and discuss the meaning of the constitutional doctrine of Parliamentary Sovereignty. Is Parliament’s right to make or unmake law according to its wishes absolute or is it subject to restrictions? The question above can be broken down into the following sub-questions: Why has Parliament the right to make or unmake any law whatever? What is Parliamentary Sovereignty? Is Parliament’s right to make or unmake law according to its wishes absolute or is it subject to restrictions? If there are restrictions what are the restrictions? How do these restrictions affect the sovereignty of Parliament? If you break down the question into appropriate sub-questions you will have a more specific and workable assignment plan to work on whereas it will also help you to structure your assignment: each of the key issues identified through this method could form a section in the assignment. Finally, you might also receive a few ‘case study’ questions on your course. These are not essay questions (as seen in the examples above). They are stories, usually inspired by real-life incidents (i.e. car accident with several people involved), which give rise to legal issues. Students are asked to identify these legal issues and advise the persons involved in the incident, like a solicitor would do. By issuing case-study questions, we are training you up for your future legal role, so it is important that your submission does ‘advise’ rather than merely ‘describe’ the law. Gathering assignment materials (general online materials for Chapter 5). As most assignments are fairly short in length, (i.e. 3,000 words), you must ensure that the information you gather is relevant to the question. Don’t get sidetracked – keep focused. Many students lose marks for going off on a tangent into an irrelevant area of law. Ask yourself: What do I need to know? What do I know already? What additional information do I need and where will I find it? Is my recording of the information useful and well organised? Use the table on the next page to plan this stage of your assignment. Make sure you give yourself a deadline for collecting the information. An excellent mix of case law, journals, statutes, and your own critical thinking will make a very impressive law assignment... bet the word count doesn’t look so generous now! MY ASSIGNMENT! Cases: Articles: Statutes/other: My opinions: Assignment Style (general online materials for Chapter 5). Assignment style In the Law School, there is a ‘house style’ for assignments, meaning the following requirements must be met when submitting your work: Double-line spaced on A4; Font Arial; Font size 12; No individual plastic wallets for individual pages; Structure your answer the same as the question (i.e. part (a) etc); Case names in main text can be in either Bold or Italic; Bibliography on the end citing all sources used; See separate referencing guide for footnoting guidance. Structuring your Assignment (general online materials for Chapter 5). A good structure certainly helps your lecturer along when marking your assignment. Start-stop structures are incredible hard to follow. It naturally flows from this that bad structures lose marks. Not because we don’t like a particular order, but because a bad structure means that the student’s legal argument (and knowledge) is all over the place. If you read a law textbook or article which did not flow very well and you could not follow the writer’s argument, would you trust it? The following structure applies to both case study and essay questions. Introduction Case study: “What is the problem?” “What area of law applies to these parties?” “What is the second issue to investigate?” “What are the potential problems when applying this area of law to this predicament?” “How am I going to investigate and analyse the problem?” Essay: “What will this assignment mainly talk about?” “What other area is relevant and how is it relevant?” “What will the writer argue towards the end?” “What evidence is he going to use?” “What will the research/evidence show?” Main body: Case study: “Describe the applicable laws and break them down into AR and MR.” “Apply the applicable laws to the scenario and the parties.” “Describe the second applicable offence/defence and break it down.” “Apply the second issue to the parties.” “Explain the final situation once all laws are applied.” Essay: “Begin with the history of this area.” “Explain the current legal position in this area.” “Critically analyse the research in this area and the direction of this area.” “State your own opinion on the matter.” “Suggest reform.” “Acknowledge a way forward for this area.” Conclusion: Case study: “Who is liable, and for what?” “What advice would you give to each party?” Essay: “Summarise the key points of your essay and make the connection with the introduction (did you prove your argument?)” The ‘essay’ main body Essays are difficult - they are a bit more ‘academic’ in nature compared to case studies, which are more ‘advisory’. Make sure you tick off the following tips when writing your ‘essay’: Each paragraph in the essay should contain only one or two main ideas, perspectives or points of view. Don’t overload your essay with your own opinions. However, you should make sure that your views are clearly visible in the essay. There is no ‘golden rule’ about how long a paragraph should be. However, avoid very short paragraphs of just one or two sentences; One effective approach is to have an opening sentence in each paragraph that introduces a view/theory. Move on then to give the relevant supporting material and legal authorities or evidence to support this opening statement, and think about how you are going to make a link with the paragraph that follows; The aim is to try and ensure a coherent and sequential flow of ideas. Key to a good structure and answer is ensuring that your paragraphs are linked in some way to create a logical progression; Words such as but, however, and on the other hand, can be used to move on to a different point or idea; Words such as in addition, furthermore, similarly, and likewise, can be used to extend a point or argument. The ‘case study’ main body Generally, case study answers require the student to be a legal advisor (i.e. act like a solicitor), but this requires knowledge of legal doctrines and authorities. In addition, application of the relevant laws to the scenario is vital in a case study answer - if you don’t apply the laws to the case study problem, you won’t get very many marks. In a problem question, the relevant legal topic(s) are not as readily apparent. A detailed analysis of the scenario will be in order. Application and advising is key in the main body. Description only simply won’t cut it. Identify the legal issues. You need to identify what aspects of the law you need to discuss in order to provide a solution to the problem. This means identifying the relevant legal issues and not simply repeating the facts of the problem; Explain the relevant law. You need to describe the relevant legal rules and principles with reference to the relevant authorities i.e. case law or statute. Only describe those rules and principles that you need to solve the problem; However, when there are more than one potentially applicable laws or principles you should explain the distinction between the competing laws and the reasons for your selection. Avoid including irrelevant material. In an academic situation, you need to be able to show that you know the law and where it is found; Apply the relevant law to the facts of the problem. You need to show how the relevant law would apply to the facts of the problem, by either distinguishing (setting apart) or relating the problem situation to legal authorities as appropriate; Reach a justified conclusion. Provide a conclusion that answers the question, i.e. summarise your advice. Concluding your assignment (general online materials for Chapter 5). Remember to link your conclusion to the title, and never introduce new ideas in your conclusion. This gives the impression of incompleteness. A conclusion: Will bring all the supporting evidence together; Can present the writer’s theory concisely and with conviction; Will sum up all the disproved evidence and distinguish it; Can illustrate the significance of the writer’s theory; Will present to the reader a way forward that is original. Many students forget to add their own conclusions to their law assessments. This gives the lecturer the impression that the piece is not finished, and marks suffer as a result. Academics who publish in the field of law can not make this mistake - they always add a conclusion at the end of their chapter or article, and Law Lords always conclude at the very end of their judgment as to what they wish the outcome of the case to be and why. As a student of law you must find these conclusions and critically analyse them. Good conclusion signals to look for include: ‘Therefore…’, ‘So…’, ‘As a consequence…’, ‘Finally…’, ‘This ought to…’, ‘As a result…’, ‘This will…’, ‘This should have…’, ‘This must…’, ‘This means that…’, ‘In effect…’, ‘This suggests that…’, ‘This indicates…’, ‘Thus…’, ‘We can thus see that…’, ‘Consequently…’, ‘Because of this…’, ‘From this we can infer that…’, ‘From this we can deduce that…’ Planning your Dissertation (general online materials for Chapter 5). Picking a topic This part is fun - what area of law are you really interested in? Perhaps you have already studied a certain topic on your course and you would like to explore an element of it further, or perhaps you would like to investigate a completely new area. Either way, it must be something that interests you, otherwise you’ll not be enthusiastic about starting or finishing - your dissertation. Murder! Immigration! In the box below, make a note of the topics which really interest you in law: My favourite law topics/subjects: Are the topics written above realistic for a dissertation, or too complex? Are they too narrow, or too wide? This is a common problem that supervisors see when meeting with dissertation students for the first time: the topic and dissertation plan is often far too ambitious. You might have a good six months to research and write, but you need to spend that time wisely, not spend all of it chasing up loose research ends. You need to pick a project topic that is feasible, which means ‘do-able’, in the short time that you have. Topics that are very wide-ranging in their focus, or rely on the collection of information which is not achievable in the time available, will cause you major frustrations later. The best dissertation topics: …are of particular interest to the student; …are simple to research. The information is easy to find, readily available, and easy to analyse; …are focused on a particular aspect of a chosen topic, not broad overviews with no depth; …are able to offer a simple structure, i.e.: introduction, history, current issue, analysis, reform, conclusion. In the box below, write your three potential dissertation titles, making sure that the four points above can be met: My top 3 dissertation titles: The following titles are examples of good, focused dissertation titles: “The law relating to provocation in voluntary manslaughter and the new three-tier proposal.” “The law of consideration in contract law.” “The Terrorism Act 2006 and the implication on human rights in the UK.” Structuring your dissertation Make sure you are clear about your formal word count before you begin to build your dissertation. You will be looking at between 7,000 and 10,000 words for a dissertation on an LLB. When you begin to build your structure, it is a good idea to allocate a word count to each section. Make sure that your structure is clear and logical - the reader will enjoy reading a piece of research which flows easily: Introduction; Background/history; Current issue; Main body; Reform; Conclusion. Types of plagiarism (general online materials for Chapter 5). Types of plagiarism There are four main types of plagiarism. a) Copy & pretend: Straight-forward copying of another person’s work, including the work of other students (with or without their consent), and claiming that it is your own or pretending that it is your own: R v Instan [1893] 1 Q.B. 450, per Darling J: “There is no case directly in point, but the prisoner was under a moral obligation to the deceased from which arose a legal duty towards her, that legal duty the prisoner has willfully and deliberately left unperformed, with the consequence that there has been an acceleration of the death of the deceased.” Plagiarised version: “The prisoner in Instan was under a moral obligation to the deceased from which arose a legal duty towards her, that legal duty the prisoner has willfully and deliberately left unperformed, with the consequence that there has been an acceleration of the death of the deceased.” Correct version: “Darling J agreed with Lord Coleridge CJ in Instan (1893) who stated: ‘there is no case directly in point, but the prisoner was under a moral obligation to the deceased from which arose a legal duty towards her, that legal duty the prisoner has willfully and deliberately left unperformed, with the consequence that there has been an acceleration of the death of the deceased’.1” b) Blend & forget: Presenting arguments that blend your work with another person’s work, but not acknowledging the other person’s work and passing it off as your own: Cottrell, S. ‘The Study Skills Handbook’ (2008) Palgrave Macmillan, at page 285: “Critical thinking when writing includes most of the elements of critical thinking when reading. It can be more difficult to analyse your own work critically, however, and to recognize and admit to your own opinion and bias.” Plagiarised version: “Critical thinking when writing includes all of the elements of critical thinking when reading. However, it is very difficult to analyse your own work critically. Students find it difficult to recognize and admit to their own opinions and views.” Correct version: “Cottrell has highlighted a common problem encountered by students when incorporating critical thinking into university assignments. She notes that students find it difficult to analyse their own work critically and to recognize their own opinions.2” 1 2 R v Instan [1893] 1 Q.B. 450, per Darling J. Cottrell, S. ‘The Study Skills Handbook’ (2008) Palgrave Macmillan, at page 285. c) Re-word & forget: Paraphrasing (re-wording) another person’s work and not acknowledging the original writer of the work; Carlill v Carbolic Smoke Ball Company [1893] 1 QB 256, per Bowen L.J.: “Was it intended that the 100I. should, if the conditions were fulfilled, be paid? The advertisement says that 1000I. is lodged at the bank for the purpose. Therefore, it cannot be said that the statement that 100I. would be paid was intended to be a mere puff. I think it was intended to be understood by the public as an offer which was to be acted upon.” Plagiarised version: “Was it intended that the 100I. should be paid if the conditions were fulfilled? The advertisement stated that 1000I. was lodged at the bank for that exact purpose. Therefore, it cannot be said that the statement that 100I. would be paid was intended to be a mere puff. It is submitted that it was intended to be understood by the public as an offer which was to be acted upon. This makes the advert an unilateral offer.” Correct version: “Bowen L.J. in Carlill v Carbolic Smoke Ball (1893) noted that the deposit in the bank was an intention to be bound: ‘the advertisement says that 1000I. is lodged at the bank for the purpose. Therefore, it cannot be said that the statement that 100I. would be paid was intended to be a mere puff. I think it was intended to be understood by the public as an offer which was to be acted upon.’3 Thus Carlill represents a unilateral offer to the whole world.” 3 Carlill v Carbolic Smoke Ball Company [1893] 1 QB 256, per Bowen L.J. d) Mixing-it-up: Colluding (working with) other students and submitting either identical or very similar work. Jamilia’s work: “Lord Smith in Peters v Coombs (1945) stated that if a defendant does not see the consequences of his actions, he cannot be liable.4 This is controversial as the earlier decision in R v Holley (1935)5 perpetuated that a defendant who does not see the consequences of his actions but is reckless towards a dangerous consequence will find liability for his actions.” Beebi’s work: “Lord Smith in Peters v Coombs (1945) stated that a defendant cannot be liable if he does not see the consequence of his actions.6 This would mean that a defendant would need to see the outcome of his act to be liable. This contrasts with the earlier decision in R v Holley (1935)7, which stated that a defendant who does not see the consequences of his actions but is reckless towards a dangerous consequence will be held liable for his actions.” Having seen these four examples of plagiarism, what are your thoughts? Do you recognise any from your own practice? 4 5 6 7 [1945] 1 All E.R. 879, per Lord Smith. [1935] 2 Q.B. 445. [1945] 1 All E.R. 879, per Lord Smith. [1935] 2 Q.B. 445.