Stipulation of Excess in Understanding and Misunderstanding Riba

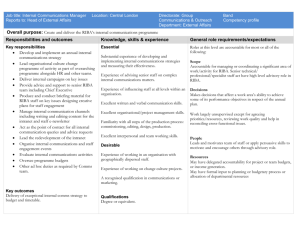

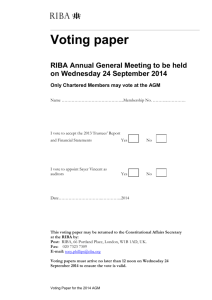

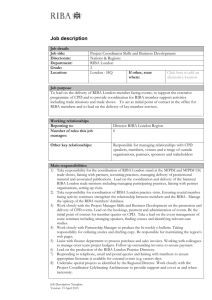

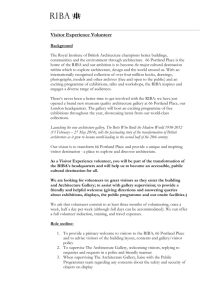

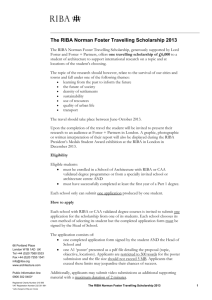

advertisement