Wage inequality and trade liberalization: Evidence

advertisement

Changes in Production and Employment Structure and Relative Wages

in Argentina and Uruguay1

Pablo Sanguinetti

Universidad Torcuato Di Tella

Rodrigo Arim

Universidad Torcuato Di Tella and Instituto de Economía,

Universidad de la Republica

Juan Pantano

Fiel and Universidad Torcuato Di Tella

August 2001

Preliminary

1

This paper has been written as a part of a project sponsored by the World Bank called “Patterns of

Integration in the Global Economy: What Does Latin America Trade? What Do Its Workers Do?. We thank

comments received from D. Lederman and two anonymous referees. As usual, all remaining errors are our

exclusive responsibility.

1. Introduction

Since the beginnings of the nineties Argentina and Uruguay have implemented

profound reforms in various areas of economic activity. These reforms, like trade

liberalization and privatization, has changed the structure of production and of

employment and also the relative demand of labor across skill levels. This may explain

the observed rising trend in wage inequality in these countries. In particular, Galiani

(1999) shows that in Argentina, contrary to what has occurred in the OECD countries, it

cannot be asserted that the returns to college graduates have increased during the eighties.

It is only since the beginning of the nineties that there is clear evidence that the college

wage premium have increased. A similar pattern has been observed for Uruguay

(Casacuberta and Vaillant (2001)).

In this paper we combine micro-data, taking from the various household surveys

and macro data, obtained from national accounts, to investigate the effects of different

shocks in aggregate labor demand composition on relative wages. One question we try to

answer is: does trade liberalization play any role in shaping the Argentine and Uruguay

wage structures during the period studied? In particular, extending the analysis presented

in Galiani and Sanguinetti (2000), we test whether those sectors where import penetration

deepened are, ceteris paribus, the sectors where a higher increase in wage inequality has

taken place. We find evidence that supports the hypothesis tested for Argentina but that

rejects it for Uruguay.

Coincidentally with the process of trade liberalization and the relative decline of

manufacturing, in these countries the non-tradable sectors have experienced a significant

expansion in production and employment. This shift in production has had also

significant effects on the relative demand of workers across skill levels. Thus in the

empirical analysis we also study whether changes in labor composition within the nontradable sector have had significant effects on relative wages. The results for Argentina

suggest that relative demand shifts in non-tradable output have had an inequalzing impact

on wage distribution. In the case of Uruguay, results are less clear cut in the sense the

1

observed raised in labor demand in services did not generate substantial differences in

wages across different skill levels.

Finally a large amount of research has sought to evaluate the effect of skilledbiased technological change on wage inequality. As most of the literature (cf. e.g.

Feenstra, 1998) we indirectly identify the magnitude of this determinant through a timing

variant dummy variable for each skill category. We obtain that this factor explains a

significant portion of the increase in wage inequality after we control for individual

characteristics, sectoral dummies, trade liberalization and shock in the composition of

labor demand across nontradables.

The rest of the paper is organized as follows. Section 2 documents the empirical

evidence about wage inequality in Argentina and Uruguay. Section 3 describes the main

change in the structure of production and employment in both countries. In section 4 we

present a simple analytical framework that will guide and motivate the regression

analysis we describe in section 5. Finally, section 6 concludes.

2

2. Trends in wage inequality in Argentina and Uruguay

In this section we study the evolution of the wage structure in Argentina and

Uruguay. In the Argentinian case, the empirical evidence available is from Greater

Buenos Aires, the main urban agglomerate.2 We measure wage differentials by

educational attainment levels. We define the ensuing three skill groups: unskilled (those

individuals who at most have attended high school but have not finished it), semi-skilled

(those that have finished high school) and skilled workers (those that have finished a

tertiary degree)3. Our study excludes self-employees, owner-managers and unpaid

workers because we are only interested in the study of the changes in the wage structure.

The results of the estimation of the wage premia by gender are shown in the figure 1.4

Figure 1: Skilled and semi-skilled workers wage premia

(Base category: unskilled workers)

Source: Galiani (1999).

2

This market covers approximately half of the labor force of the country.

Galiani (1999) shows that this is the relevant classification of educational skills when analyzing the

evolution of wages.

4

These estimations are derived from the coefficients of a wage equation where the dependent variable is

the logarithm of the hourly wages and among the covariates there is a set of educational dummies and a

quadratic function in potential experience. The equations are estimated separately by gender. The

dependent variable is the logarithm of the hourly earnings of the sampled individuals in their main

occupation. For employees, this variable is equivalent to the hourly wages. The schooling group g wage

premium in year t is the expected percentage increase in the wage of a worker whose level of education is g

with respect to the expected wage of an unskilled worker. The yearly data is taken from the October wave

of the Household survey for Greater Buenos Aires (GBA). There are not data tapes available for the years

1983 and 1984.

3

3

For the whole period, the main changes in the wage structure are the following:

the semi-skilled group has become more like the unskilled group as time has passed, that

is, they have seen their wages deteriorated relative to the unskilled group wages.

Additionally, the unskilled group has not seen its wages deteriorate relative to the skilled

workers wages. For example, the male skilled wage premium was 228 percent in 1980,

156 percent in 1991 and 211 percent in 1998 while the male semi-skilled wage premium

was respectively, 87, 44 and 48 percent.

Nevertheless, if the analysis is restricted to the evolution of wages during the

nineties, the period when trade liberalization was deepened, we see a somewhat different

picture. The wages of the semi-skilled group did not deteriorate relative to the unskilled

group wages while both the unskilled and semi-skilled wages deteriorated relative to the

skilled group wages. Indeed, the skilled-unskilled wage premium increased substantially

during the 90s.

Figure 2 illustrates the evolution of the wage premia for the manufacturing

sector.5 Due to sample size considerations we present only an average wage premium by

skill group. It is manifest from the figure that the trends we observe in the manufacturing

sector during the nineties are similar to those we observe for the whole economy. We find

a significant positive trend in the college wage premium. On average, it increased

approximately 7 percentage points per year during the nineties while the secondary

school wage premium slightly decreased but not significantly.6 Thus, overall, we may

conclude that during the nineties, the trends in the wage structure in the manufacturing

sector are quite similar to those for the whole economy.

5

These statistics are derived from the coefficients of a wage equation where the dependent variable is the

logarithm of the hourly wages and among the covariates there is a set of educational dummies, a quadratic

function in potential experience and a gender dummy. The dependent variable is the logarithm of the hourly

earnings of the sampled individuals in their main occupation. The yearly data is taken from the October

wave of the Household survey for Greater Buenos Aires (GBA).

4

Figure 2: Skilled and semi-skilled workers wage premia

in the manufacturing sector, Argentina

(Base category: unskilled workers)

400

350

300

250

200

150

100

50

0

%

Tertiary wage Premium

Secondary school wage Premium

1990 1991 1992 1993 1994 1995 1996 1997 1998

Source: author’s elaboration.

For Uruguay we use the microdata from household surveys for the period 19861997. In this case, we had access to the whole dataset not only the main metropolitan area so

the result extend more naturally to a national (urban) interpretation. Table 1 displays the

logarithmic change in hourly real wages for urban Uruguay for different periods and

different educational levels. We can draw some interesting conclusions regarding the

evolution of relative wages. The overall rate of growth in wages is similar for both periods

(1986-1990 and 1991-1999) and will be our benchmark point of reference to evaluate the

performance of wages for different educational levels. It is interesting to note that in the

second half of the eighties Complete Primary and Complete Secondary were the sectors

with the largest wage increases, while higher educational level wages performed from

moderate growth (Incomplete College) to disappointing 1.1 (complete college) and –0.5

(Professors). The picture is the exactly the opposite in the nineties with higher educational

levels wages growing clearly faster than those corresponding to lower of education like

incomplete/complete primary and secondary.

6

Indeed, like for the entire economy, the rise in the skilled workers wage premium started in 1992. It is

also worth noting that the 1995 value of this statistic is extremely high in the manufacturing sector.

However, it may be even due to sampling variability or mesurement error.

5

Table 1 Logarithmic Change in Real Hourly Wages by

educational level, Uruguay

educational level

1986/1991 1991/1999 1986/1999

Primary school

14.9

9.9

24.8

Incomplete high school

11.4

6.2

17.5

Complete high school

18.1

4

22.1

Technical education

16.7

8.7

25.4

Teachers

-0.5

25.8

25.3

Incomplete collage

9.2

18.3

27.5

Complete collage

1.1

32

33.1

Overall

11.7

11.5

23.2

Source: Arim and Zoppolo (2000)

As we did with the case of Argentina, we will aggregate the different levels of

education into three groups. Still as in Uruguay incomplete college wages are closer to

complete college ones, we prefer to categorize Uruguayan skill groups differently. So, the

high skill group for Uruguay includes complete as well as incomplete college workers.

Workers with complete and incomplete high school compose the semi skill group. The

remaining workers (those with at most complete primary education) are in the low-skill

group.

Figure 3 shows the evolution of the wage premia at the manufacturing sector for

Uruguay. We present the evolution of the collage and high school premium with respect

to the wage of a worker with only primary complete school. We observe that also in

Uruguay, for both men and women, there has been an increase in college wage premia

6

especially in the nineties. Thus, the observed pattern for both countries is very similar

also at the manufacturing sector.

7

. Figure 3: Skilled and semi-skilled workers wage premia

in the manufacturing sector, Uruguay

(Base category: unskilled workers)

A-Men

College premium

High School premium

350%

300%

250%

200%

150%

100%

50%

0%

1986 1987 1988 1989 1990 1991 1992 1993 1994 1995 1996 1997 1998 1999

B- Women

(Base category: unskilled workers)

College premium

High School premium

300%

250%

200%

150%

100%

50%

0%

1986 1987 1988 1989 1990 1991 1992 1993 1994 1995 1996 1997 1998 1999

Source: authors elaboration based on household surveys

8

3. The changes in the production and employment patterns

In this section we want to revise the evidence regarding changes in sectoral composition

of production and employment in these economies, which could potentially explain part

of the described movements of wage inequality. We start analyzing the evolution of

production structure for both countries. Afterwards, we analyze the change in the

employment structure and the differences in the sectoral requirements of human capital.

The type of question we want to address here are: which are the sectors where

production and employment expanded and which were the declining sectors? How does

the allocation of labor skills varied across time and across sectors of the economy?

3.1. Production patterns

A. Argentina

The evolution of aggregate GDP for Argentina shows a marked contrast between the

eighties and the nineties. During the first decade GDP falls 10% while in the nineties

GDP raises approximately 37% (see figure 4). This result is not a surprise taking into

account the deep and far reaching reforms that the country has experienced since 1991.

Within these reforms inflation stabilization has had a strong impact in spurring aggregate

demand, which has plunged since late 1988 as a consequence of the hyperinflation

process suffered by the economy. Nevertheless, the strong growth that we observe since

1991 was not only a cyclical recuperation from a low level of output. Several estimations

(see Kydland and Zarazaga, 1997) suggest that the potential GDP of Argentina have

change its tendency during this period as a consequence of the increase in capital

accumulation that was spurred by the reforms policies such as trade and investment

liberalization.

9

Figure 4

GDP (pesos 1993)

GDP

300,000,000

250,000,000

200,000,000

150,000,000

100,000,000

50,000,000

Year

0

Source: INDEC.

Beyond what has happen with aggregate GDP, from the point of view of this paper, we

are interested in analyzing the changes that may have occurred in the structure of

production during these two periods. Table 2 presents the structure of GDP disaggregate

at 1 digit of the ISIC since 1980.

10

Table 2. GDP Structure. Argentina

in %

Year

Transport

Agricult

Electricity,

Retailing

Financial Public

and

ure and Mining Industry Water and Construction and Hotel

and real Administ

telecomuni

Fishing

Gas

services

state

ration

cation

1980

5.12

1981

5.51

1982

5.98

1983

5.90

1984

5.82

1985

6.11

1986

5.71

1987

5.42

1988

5.96

1989

5.86

1990

6.53

1991

6.16

1992

5.67

1993

5.49

1994

5.56

1995

6.03

1996

5.65

1997

5.26

1998

5.47

1999

5.72

2000

5.61

Source: INDEC.

1.42

1.46

1.46

1.45

1.41

1.46

1.27

1.33

1.43

1.53

1.61

1.50

1.53

1.59

1.71

2.04

2.02

1.89

1.74

1.70

1.88

21.10

19.39

19.39

20.20

20.43

19.71

20.50

20.18

19.65

19.47

19.25

19.24

19.72

19.50

19.18

18.29

18.48

18.68

18.20

17.28

16.90

1.46

1.54

1.66

1.72

1.83

2.00

1.93

1.98

1.88

1.92

2.12

1.98

1.98

2.08

2.17

2.39

2.36

2.37

2.44

2.60

2.79

8.52

7.80

7.25

6.93

6.07

5.53

6.20

6.92

6.84

5.54

4.52

5.35

5.78

6.05

6.03

5.44

5.60

6.04

6.28

5.93

5.29

19.10

18.18

17.17

17.45

18.22

17.37

17.28

17.00

16.65

16.64

17.05

17.84

18.17

17.76

17.85

16.96

17.36

17.83

17.64

16.97

16.70

5.82

5.72

6.01

6.03

6.34

6.64

6.69

6.74

6.75

7.16

7.12

7.11

7.33

7.29

7.57

7.91

8.03

8.27

8.61

8.75

8.90

18.21

20.20

20.18

19.55

19.00

19.67

19.59

19.35

19.38

19.12

18.59

19.14

18.90

19.63

20.24

20.59

20.74

20.61

21.11

21.79

22.27

19.26

20.20

20.91

20.76

20.89

21.52

20.83

21.07

21.46

22.77

23.22

21.68

20.91

20.59

19.70

20.35

19.76

19.04

18.49

19.26

19.66

Two trends are clearly observed from the data. On one hand, industry has been losing

importance in terms of its participation in GDP. It was around 20% in the beginning of

the 80s and ended up with a share near 17 % in year 1999- 2000. Most of the decline in

this participation has occurred during the nineties; in 1991-1992 industry participation

was around 19.5, which was pretty close to the average of the eighties. The second clear

trend was the increase in participation in the service sector. Its share was 43% of the GDP

in 1980 and increased to 48% in year 2000. Again, most of the increase in this share has

happened during the nineties. Within the service category the ones that increase the most

were electricity, gas and water, transport and telecommunication and financial services

11

total

100

100

100

100

100

100

100

100

100

100

100

100

100

100

100

100

100

100

100

100

100

and services to firms. Clearly the raise in the first two activities is associated with the

privatization policies adopted by Argentina at the beginning of the nineties; on the other

hand, the expansion of financial services has been a consequence of the stabilization

policies which implied an important increase in the degree of monetization of the

economy.

Regarding the other sectors, primary, the least important of all, experienced an erratic

behavior in terms of its share, reflecting the volatility of prices of these commodities. For

example, Agriculture and Fishing’s share remained pretty stable between the two extreme

years of the period while we observe temporary rises in some years in concordance with

the behavior of agricultural prices. On the other hand, we observe an increasing trend in

mining, which took place since the beginning of the nineties, though it was partially

reverted at the end of the decade when international prices for these products suffered

sharp declines.

Finally, construction shows a declining tendency over the period, which was mainly

produced during the eighties. The share corresponding to public sector activities has also

remained stable between the extreme years of the period though it rose at the end of the

eighties as a consequence of the sharp recession that affected the rest of the activities

during the hyperinflation episode.

B. Uruguay

The evolution of GDP in Uruguay during the last 15 years shows a gradual process of

recuperation of the economy after the stagnation suffered in the first half of the eighties.

Thus between 1986 and 1991 the economy grew at an annual rate of 1.8%. Afterwards in

the nineties the growth rate accelerated, reaching an average value of 4.1% between 1991

and 1999.

12

The structure of production has also undergone significant changes in last two decades

as illustrated by the data presented in Table 3, where we show a disaggregation of GDP

by 1-digit sector of the ISIC classification for selected years.

Table 3: GDP Structure. Uruguay

1986

1988

1994

1999

12.7

8.7

7.7

5.5

0.1

0.1

0.2

0.2

29.7

26.5

18.3

16.0

4 Electricity, gas and water

3.6

2.6

3.1

3.8

5 Construction

2.7

3.6

5.7

5.8

12.6

14.6

16.5

13.5

6.4

6.5

6.9

8.4

8 Financial Institutions

18.3

21.1

22.8

26.2

9 Public sector and other services

14.0

16.2

18.8

20.6

1 Agriculture/cattle

2 Mining

3 Manufacturing

6 Retailing ad hotel services

7 Transportation and telecommunications

Source: Banco Central del Uruguay

As was the case in Argentina, manufacturing is the sector for which we observe the

most significant fall in GDP participation between 1986 and 1999. Industry represented a

29.7% of GDP in 1986 and fell to around 17.0% in 1999. Again, similarly with

Argentina, most of the fall in the participation took place in the nineties, especially in the

first half of the decade. The other sector that losses participation is primary production

mainly by the reduction in participation of Agriculture and cattle (fishing is negligible in

the case of Uruguay). The share of primary production was 12.7% in 1986 and went

down to 5.5% in 1999. Compared to industry, the decline of the share in this sector has

been a more continuous process, which took place along the whole period.

The sectors where we find an expansion in production above the average are those

related with certain services. This is notably the case of financial institutions and services

to enterprises, for which the share went up from 18.3% in 1986 to 26.2 in 1999.

13

Construction was also another sector that increased its participation in total production,

especially during the nineties. The activity associated with public sector and other

services (sector 9) has also expanded its production above the average, increasing its

share from 14.4% in 1986 to 21.3% in 1999. On the other hand for retail, restaurants and

hotel services we find similar shares in 1986 and 1999, though there was a temporary

raise in it at the end of the eighties and beginning of the nineties.

3.2. The evolution of employment structure

To what extend does the above changes in the production structure has been translate to

the structure of employment? In this section we will look at this issue describing the

evidence on the sectoral allocation of labor across major industry and services sectors of

the economy. The aim is to identify shift in labor demand across sectors of the economy

that may have been induced by the above-described change in the structure of production.

A.

Argentina

The evidence from the Permanent Household Surveys shows that there was a

significant decline in the employment share for almost all manufacturing sectors during

the period under analysis. For the aggregate of industry the reduction was equal to 10

percentage points (see Table 4) and it occurred mostly during the nineties. This fall was

compensated by increases in some services, mainly business and financial services,

which expanded overall from 7.8% in 1985 to 11.5% in 1999. Table 5 shows that the

reduction in manufacturing employment is more important for Textile and Footwear,

falling from 8.2% in 1985 to 3.5% in 1999. These sectors are the usual reference as an

example of the negative impact of trade liberalization on employment in the industrial

countries.

Given that the survey coverage is only urban, primary sector employment share is

substantially underestimated and, as a consequence, manufacturing and services

employment shares are overestimated. Figure 5 shows the employment level evolution

14

for the 8 aggregates highlighted in the previous table. As we can see, not only the

manufacturing sector lost share in total employment but there was also a significant

decline in the absolute level of employment.

Table 4 Employment share by selected sectors , Argentina

Sector

Primary products

Manufacturing Sector

Food Drinks and Tobacco

Textile and Footwear

Chemical Productos

Metalic products

Other Industries

Electricity, Gas and Water

Construction

Trade, Hotels and Restaurants

Major Trade

Retail trade

Hotels and Restaurants

Transportation and Communications

Transportation

Transportation related services and comunications

Bussinnes and Financial Services

Finance

Real estate and businnes services

Social and Personal Services

Public Administration and Defense

Teaching

Social and Health services

Other social services

Repair services

Housekeeping

Other personal services

Source: Authors calculations based on EPH

15

1985

1990

1994

1999

0.3

26.1

3.5

8.1

3.1

6.3

5.1

0.2

6.9

18.6

3.6

13.1

1.9

7.2

5.8

1.4

7.8

1.6

6.2

32.9

4.0

5.2

4.0

3.8

3.1

8.2

4.6

0.4

24.0

3.3

6.2

3.1

6.1

5.2

0.8

6.2

20.1

3.7

13.9

2.6

8.0

6.4

1.6

7.2

2.3

4.9

33.2

5.1

5.7

5.1

4.0

2.5

9.2

1.6

0.4

21.3

3.5

4.1

2.5

6.3

4.9

0.7

7.1

20.7

5.5

12.1

3.1

9.2

6.6

2.6

9.2

2.8

6.5

31.5

4.7

6.3

4.9

3.7

3.1

7.6

1.2

0.4

17.3

2.8

3.4

2.9

4.6

3.5

0.4

7.6

19.3

4.6

11.5

3.3

9.7

6.6

3.1

11.5

2.8

8.7

33.8

5.1

7.0

5.4

4.4

2.8

7.8

1.4

Figure 5

Evolution of Employment by selected sectors (thousands), Argentina

('000)

1200

2500

1100

2300

Social and Personal Services

Manufacturing sector

1000

2100

900

1900

1986

80

1988

1990

1992

1994

1996

1998

Electricity, Gas

and Water

1986

350

70

300

60

250

50

1990

1992

1994

1996

1998

1990

1992

1994

1996

1998

1992

1994

1996

1998

1992

1994

1996

1998

Construction

200

1986

1988

1990

1992

1994

1996

1998

950

850

1988

1986

1988

500

Trade, Hotels and

Restaurants

450

Transport and Communications

400

750

350

650

1986

500

1988

1990

1992

1994

1996

1998

Bussines and Financial Services

1986

50

400

1988

1990

Primary Sector

40

year

300

1986

30

1988

1990

1992

1994

1996

1998

1986

1988

1990

Source: Galiani and Sanguinetti (2000)

B.

Uruguay

Similarly to Argentina, in Uruguay manufacturing is the most affected sector in

terms of lost of employment (see Table 5). Again for this economy the bulk of the decline

is concentrated in the nineties. As we see from the table, between 1986 and 1990

manufacturing sector employment share remains relatively stable or even increases

slightly. The 5-percentage points decline in the share occurred between 1990 and 1999,

which seems moderate compared to the case of Argentine.

16

Table 5 Employment share by sectors, Uruguay

Sectors

1986 1990 1994 1999

Agriculture, Hunting, Fishing

Mining

Manufacturing

Electricity, Gas and Water

Construction

Retail Trade, Restaurants and Hotels

Transportation, Storage and Communication

Financial and Bussinnes Services

Personal, Social and Comunal Services

4.3

0.2

20.6

1.7

5.1

17.8

7

4.5

38.8

3.4

0.2

21.1

1.5

6.6

17.8

6

4.8

38.5

4.4

0.1

19.2

1.2

7.3

19.2

6

5.9

36.6

3.9

0.1

15.9

1

8.4

19.8

6.1

6.5

38.3

Source: authors elaboration based on ECH and information from BCU

The most dynamic sectors displaying increases in their employment shares are

Construction and Financial and Business services. However, preliminary and more

disaggregated computations show that the majority of this increment is due to business

services and not to financial services. The other sectors remain relatively constant all

along the period.

3.3 Human capital requirements across sectors

In this section we briefly summarize the changes in human capital requirements across

different sectors for Argentina and Uruguay. We will use the same three educational

levels defined for each country in section 2.

A. Argentina

Table 6 displays the human capital requirements by sector corresponding to Argentina.

We observe substantial movements in all activities towards a more high skilled intensive

form of production. This is reflected in a widespread decline in the low education

intensity of employment across all sectors7. This process coincides with the increase in

relative supply of skilled workers that took place during this period (Galiani (1999)). On

7

We neglect Primary Products given the urban coverage of the survey and other sectors with a very small

number of observations like Electricity, Gas and Water.

17

the other hand, we see that sectors that ranked among those with higher human capital

requirements in 1986, like Business and Financial Services or Personal and Social

Services, still remain in that condition in 1999. On the other extreme, manufacturing was

both, in 1986 and in 1999, one of the activities that most intensively used low skilled

workers.

This different human capital requirements across sectors could have had

important consequences on the behavior of relative demand for skilled and unskilled

labor (and for relative wages), if, as we observed in Argentina, manufacturing

employment falls while the employment of Business and Financial Services rises.

18

Table 6 Human Capital requirements by sectors , Argentina

Education level

1986

Sector

Primary products

Manufacturing Sector

Food Drinks and Tobacco

Textile and Footwear

Chemical Productos

Metalic products

Other Industries

Electricity, Gas and Water

Construction

Trade, Hotels and Restaurants

Major Trade

Retail trade

Hotels and Restaurants

Transportation and Communications

Transportation

Transportation related services and com.

Bussinnes and Financial Services

Finance

Real estate and businnes services

Social and Personal Services

Public Administration and Defense

Teaching

Social and Health services

Other social services

Repair services

Housekeeping

Other personal services

1999

Low

Medium

High

Low

Medium

High

56%

76%

84%

82%

63%

73%

74%

38%

87%

73%

65%

74%

88%

73%

77%

57%

29%

33%

27%

64%

54%

17%

41%

63%

84%

97%

73%

25%

21%

15%

17%

29%

22%

22%

62%

9%

23%

30%

24%

12%

23%

19%

36%

48%

57%

43%

21%

33%

44%

21%

24%

15%

3%

22%

19%

4%

1%

2%

8%

5%

5%

0%

4%

3%

4%

3%

1%

4%

3%

7%

24%

10%

30%

15%

13%

39%

38%

13%

1%

0%

5%

59%

60%

71%

68%

49%

50%

65%

55%

83%

58%

43%

61%

67%

61%

69%

44%

20%

11%

23%

48%

39%

13%

28%

55%

69%

86%

52%

6%

33%

26%

30%

39%

40%

30%

30%

14%

36%

45%

34%

30%

33%

27%

46%

50%

65%

45%

28%

42%

33%

22%

35%

27%

12%

43%

35%

7%

3%

3%

12%

10%

5%

15%

3%

6%

13%

5%

3%

6%

4%

10%

30%

24%

32%

24%

18%

54%

50%

10%

4%

2%

5%

Source: Authors calculations based on EPH

B. Uruguay

The change in human capital requirements in Uruguay is very similar to that of

Argentina. On the supply side, there is a significant rise of the educational level of the

labor force. Coinciding with this phenomenon, almost all sectors increase their tertiary

labor intensity (see Table 7). We also observe that sectors that were more intensive in

tertiary level employment in 1986, mainly services sectors, remained also very intensive

19

in the use of this factor in 1999 (e.g. Real Estate and Business services, Finance and

Insurance and Social services, etc). In addition these sectors were those where

employment expanded the most. We may suspect that this change in relative demand

could have affected relative wages between skilled and unskilled workers. We

empirically investigate this hypothesis in section 4.

Table 7 Human Capital requirements by sector, Uruguay

Education Level

Sectors

1986

1999

Primary Secondary Tertiary

Primary Secondary Tertiary

Agriculture, hunting, mining

77.6

Food Drinks and Tobacco

57

Textile and Leather

49.6

Wood

46.3

Paper and paper products and printing35.2

Chemical products

43.2

Metalic products, machines and eq. 38.5

Other manufacturing iindustries

38.1

Eletricity, Gas and Steam

43.1

Water and Hidraulic Projects

40

Construction

69.7

Major Trade

40.5

Retail Trade

40.8

Restaurants and Hotels

58.2

Transportation and Storage

49

Comunications

33

Finance and Insurance

13.2

Real Estate and bussiness services 14.9

Public Administration and Defense 42.5

Social Services and other Comun. Serv.

23.4

Entertaining

43.4

Personal Services

67.3

20

40.5

47.6

52.7

57

51.8

58

58.6

50.1

49.9

28.8

52.9

55.2

40.2

48.8

57

74.5

66.8

49

40.6

50

31.7

Source: authors calculations based on ECH microdata

20

2.3

2.5

2.8

0.9

7.8

6.7

4.5

3.3

6.9

10

1.5

6.7

3.9

1.6

2.3

9.9

12.3

18.3

8.5

36

6.6

0.9

59.4

35.3

31.8

29.3

17

23.7

26.4

17

18.7

36.8

54.6

18.6

19.7

30.6

31.2

11.7

3.5

10.2

27.2

12.7

25.5

49.6

34.5

59.7

65.4

68.3

69

60.4

67.5

75.7

60

49.6

43

67.7

70.8

62

61.6

66.4

57.2

54.9

57.9

39.8

54.3

48.3

6.1

4.9

2.8

2.5

14.1

15.8

6.1

7.3

21.4

13.6

2.4

13.6

9.5

7.4

7.2

21.9

39.3

35

14.9

47.5

20.2

2.1

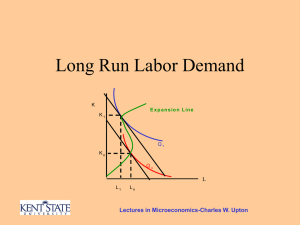

4. Change in the production and employment structure and wage inequality: a

theoretical background.

We consider the simplest labor market model where there are two labor inputs

represented by skilled and unskilled workers. Figure 6 shows the determination of

relative employment and relative wages between the two kinds of workers at a

competitive equilibrium, after a supply (panel a) and demand (panel b) shock.

Figure 6

S’

S

S

W1

h

W

1W

W0

0

D’

D

D

E’ E

E

Panel a

E’

Panel b

As shown in panel a, an exogenous increase in the supply of skilled workers will reduced

the relative wage of those workers. On the other hand, if the demand curve moves

upwards, the relative wage and the participation in the employment of skilled workers

rises (panel b of figure 6).8 Since the evidence points out that in Argentina and Uruguay

the relative supply shifted in the nineties in favor of skilled workers while, at the same

time, the wage differential rose, the change in the composition of the labor supply cannot

be a plausible explanation behind the observed change in the wage inequality in both

countries. To explain the observed facts we have to bring in stories associated with

changes in the relative demand. Indeed a focal point in the literature about the evolution

of wages differentials in the last two decades has been to identify the different forces that

21

potentially explain the change in the structure of labor demand in favor of skilled

workers.

Several arguments can be distinguished. Some authors have stressed the consequences

of trade liberalization on labor markets (Lawrence and Slaughter (1993), Leamer (1995),

(1998)). The effects of trade on wage inequality are analyzed in the simple framework of

Hecksher-Ohlin (H-O) model with two tradable goods and two non-tradable labor factors,

skilled and unskilled work. In this context, the Stolper-Samuelson theorem, expresses the

basic transmission mechanism that relates the international trade and the wage structure

of a country. Its simplest version establishes that a fall in the relative price of one of the

goods leads to a reduction in the real returns of factor that is used intensively in its

production and a concomitant increase in the returns of other factor. Thus, if international

competition causes a reduction of prices of products that used intensively low-skilled

labor, then we would observe a raise in the wage skilled premium. The (H-O) model

assumes perfect mobility of workers across sectors so it is not a good framework to look

at industry sectors within a given country. Galiani and Sanguinetti (2001) show that a

negative effect of trade liberalization on low skilled relative wages can also be expected

in a economy where it is assumed that low skilled labor is less mobile compared to high

skilled labor. This allows to empirically identifying the effect of trade shocks on the

structure of wages using cross industry data.

Beyond trade liberalization, other authors have argued that the changes in the relative

demand for labor are associated to alterations in the overall productive structure of the

economies that evolves towards sectors that use skilled labor more intensively (Bernard

and Jensen 1998). In special, the lost of participation of manufacturing sector in the GDP,

and the concomitant raise of certain type of skilled–intensive services would be a process

that generates a reduction in the relative demand of less skilled workers.

8

Of course, the size of the change in the relative wage and employment will depend on the elasticity of

supply and demand curves.

22

Finally, another key explanation articulates around the notion of biased technological

change, highly complement of skilled labor, but substitute of unskilled labor (Acemoglu,

2000; Berman and Bradford (1998), Berman et al (1998)). This type of shock would be

the main force shifting the relative demand curve upwards to the right, increasing the

wage premium of skill workers. These authors argued that in the last two decades there

has been an acceleration of technological change that determined an increase of the

marginal productivity of skilled workers greater than the registered by unskilled workers.

This phenomenon would explain the increase of the wage differentials in favor of more

skilled worked

5.

An empirical test of the impact of trade liberalization and changes in non

tradable production structure on wage inequality.

In this section we will try to investigate empirically the determinants of relative wages in

Argentina and Uruguay. In particular we will try to assess whether some the forces we

identify in the previous section have any bearing with the behavior of actual data.

To do this, we start to focalize on the effect of trade liberalization on the structure of

labor demand and relative wages in the manufacturing sector. Afterwards, we generalize

our analysis incorporating the non-tradable activities so as to take into account the effect

of changes of production and employment patterns in the whole economy on wage

inequality. Finally, from the estimation of the time varying dummies for the skill levels

we assess the impact on wage inequality of skilled bias technological change.

5.1 Relative wages and trade liberalization

In this section we study whether the deepening of trade liberalization has had any

identifiable impact on the structure of wages in Argentina and Uruguay. Specifically, we

test, using micro data, whether or not those manufacturing sectors where import

penetration deepened are, ceteris paribus, the sectors where occurred a higher increase in

wage inequality by skill group. Galiani and Sanguinetti (2000) show that the degree of

import penetration has increased in most manufacturing sectors in Argentina during the

23

nineties. This rise in foreign competition was not uniform across sectors. Thus, we are

able to investigate whether, after we control for several individual characteristics, it is the

case that relative wages widened comparatively more in those sectors that faced strongest

competition from foreign markets.

In order to test the hypothesis that import penetration plays a role in shaping wage

inequality, we estimate the coefficients of the following regression function:

Log ( wijt ) dsijgt gt dsijgt m jt gm dtijct ct f t (ageijt ) dsexijt t ct j uijt

g _1

g

(1)

c _1

where dsijgt is a dummy variable that indicates schooling group g in period t, and gt is a

schooling effect in period t; mjt is the logarithm of the ratio of imports to gross value

added in the manufacturing sector j in period t. dtijct is a dummy variable that indicates

tenure group and ct is the tenure effect in period t. The tenure groups are: (0,1), [1,5),

[5,10), [10,20) and [20,20+). ft(ageit) is a non-linear function of the age of individual i in

period t, which is linear in the coefficients to be estimated. dsexijt is a dummy variable

indicating the gender of individual i and t is the gender impact on wages in period t; ct is

the intercept in period t (the period effect); j is the sector fixed-effect, and uijt is the

error term for individual i working in sector j during period t.

The dependent variable is the logarithm of the hourly earnings of the sampled

individuals in their main occupations. The schooling groups are the unskilled group, the

semi-skilled group and the skilled group defined in section 2 (note that skill

categorization differs between Argentina and Uruguay). For Argentina, the micro data on

wages comes from the household survey for the period 1992-1999 for both waves of the

year (May and October). For Uruguay we use the Continuous Households Survey (ECH)

(conducted annually, each one all along the year) corresponding to the 1987-1997

period.. Thus, in each case, the period effect refers to the wave-year or year effect. The

Argentine data on imports, exports and value added by two-digit sector is taken from the

Argentine International Trade Commission. In the case of Uruguay we have taken trade

24

data from Data Intal and value added data from Annual Manufacturing Survey from INE

(Instituto Nacional de Estadística, Uruguay) .

We estimate equation (1) by sampling only the workers of the manufacturing

sector because they are the only group of workers for which the measure of import

penetration adopted presents variability. For Uruguay we previously transform trade data

from ISIC Rev 3 to ISIC Rev 2 in order to compute import penetration ratios with

production data that it is only available at ISIC Rev 2 disagreggation. For Argentina we

work with the 2-digit sectors defined by ISIC Rev 3.

Thus, under the specification adopted for our test, the schooling group g wage

premium in sector j in year t is given by WPjgt = 100 [Exponential(gt + (gm - bm) mjt) –

1], where bm is the estimated coefficient in the regression function 1 for the educational

base category. Consequently, at a first stage, the set of gm are the parameters of interest

in our study. Given our hypothesis, that is, that the relative wages widened comparatively

more in those activities that faced strongest competition from foreign markets and the

evidence gathered in section 2, we expect the difference among the coefficients of the

skilled group and the other two skill groups to be positive. Additionally, we may also

expect these two differences to be statistically similar.

Note that our estimate of the impact of import penetration on wage inequality are not

necessarily an estimate of the whole effect of the former on the latter, that is, it is not

necessarily an estimate of the general equilibrium effect which may not be identifiable.

For example, if trade liberalization shifts labor demand against the unskilled in some

manufacturing sectors and labor is highly mobile, it would be the case that the wages of

the unskilled workers are adjusted in every sector of the economy and hence, the

correlation between the degree of import penetration and wage differentials by sector

vanishes. However, as shown in Galiani and Sanguinetti (2000), under certain

technological conditions or rigidities in the adjustment of the economy, an increase in

import penetration may widen income inequality relatively to the rest of the economy in

the sectors affected. Our test evaluates the existence of these differential effects in the

manufacturing sectors. If we do not find any effect, it is still plausibly, at least

25

theoretically, that import penetration may be shaping wage inequality. Instead, if we do

find an effect from the degree of import penetration on wage inequality, this effect may

not necessarily be an estimate of the general equilibrium effect: it would just be the

identifiable effect.

Note the similitude of our regression model and the wage curve model of

Blanchflower and Oswald (1994). We control both for period fixed-effect and sectorfixed effect. Thus, our model does not provide information about the level of wages by

sector because we are conditioning our estimates on the sample means by sector. In our

model the curve would be drawn in the plane of wage premium and sector import

penetration instead.

It is worth noting that in the specification of the regression function (1) we control

for any aggregate shock that affect wages homogeneously. Thus, for example, if inflation

affects all wages in the same way, it would be captured by the period effect. If instead we

have that some other determinants, for example, technological change, that affects wages

differently by skill group, it would be captured by the wage premium that we allow

varying by period. The latter is an important feature of the specification adopted, which

permits us to estimate the significance of these residual factors affecting relative wages.

On the other hand, the set of parameters gm should only capture the impact on wages of

the sector import penetration.

Galiani and Sanguinetti (2000) show that the estimated coefficients for the variables

controlling for individual characteristics (education level, age and tenure) are as

expected. Next, we report the main results from Galiani and Sanguinetti (2000) for the

Argentine case and new results based on the extension of their methodology to Uruguay.

Table 8 and 9 (for Argentina an Uruguay, respectively) presents the estimated

coefficients of the parameters of interest, those associated with the interactive variables

of education levels and import penetration. The reported standard errors are consistent

standard errors although the errors in the regression function (1) may lack independence.

26

In particular, they are robust to the problem of random group or cluster effects in the data

(cf. e.g. Huber, 1967 and Moulton, 1986).

In the case of Argentina, the coefficients of the interactive import penetration

variable corresponding to the three education level are positive and significant, Galiani

and Sanguinetti (2000) show that this result is robust to alternative specifications (like

controlling for export penetration and for changes in sector prices). Most important, the

coefficient of the skilled group is positive and higher than the coefficient of the other two

skill groups, which have similar estimated values. Thus we find evidence that shows that

in those manufacturing sectors where the import penetration increased the most, wage

inequality also widened relatively more in favor of the most skilled workers.

Table 8: Coefficients (standard errors) of import penetration-skill interaction

variables on wages by skill group, Argentina.

Variable

Coefficient

Robust

standard

error

Unskilled

dummy

*

0.067

0.035 **

Semi-skilled dummy *

0.060

0.035 *

0.125

0.048 ***

import penetration

import penetration

Skilled dummy * import

penetration

Notes: *** if the coefficient is statistically different from zero

at the one percent significance level. ** if the coefficient

is statistically different from zero at the five percent significance

level. * if the coefficient is statistically different from zero at the

ten percent significance level.

27

Table 9: Coefficients (standard errors) of import penetration-skill interaction

variables on wages by skill group, Uruguay.

Variable

Coefficient

Robust

standard

error

Unskilled

dummy

*

import penetration

Semi-skilled dummy *

import penetration

Skilled dummy * import

.001172

.007361

5

.017411

.00706*

2

*

.008952

.013175

penetration

Notes: *** if the coefficient is statistically different from zero

at the one percent significance level. ** if the coefficient

is statistically different from zero at the five percent significance

level. * if the coefficient is statistically different from zero at the

ten percent significance level.

The identified effects for Uruguay are rather weak. Particularly, only the semi-skilled

import penetration interaction is significant and the implied effect on wage inequality is

not so clear for this case. If anything, import penetration will be acting against the trend

observed in section 2 where high skilled wages raised relative to semi-skilled wages.

Still this unintuitive result disappears when, as we will see next, we incorporate the

nontradable sectors in the empirical analysis. Overall, the weak results regarding the

import penetration variable in Uruguay (as compared to Argentina) is also consequence

of the fact that data from the Continuous Household Survey allows disaggregate the

manufacturing sector in only nine activities (we have twenty one in the case of

Argentina).

We partially conclude that there is scope for trade liberalization to explain the

increase of the skilled group wage premium during the 90s only for Argentina. Thus, at

least partially, the aggregate trends on wage differentials we presented in section 2 may

be explained by the impact on trade liberalization on wages. However, the identified

28

effect of trade liberalization on wage inequality does not explain much. Even though the

average (weighted by employment) imports to sector value added increased

approximately 80 percent during the period studied, the average identifiable increase in

the skilled wage premium due to trade liberalization in the manufacturing sector is

approximately 5 percentage points, which is only 10 percent of the increase in the skilled

wage premium during the same period.

5.2 An empirical extension including the non tradable sectors.

We now turn to the extension incorporating non-tradable sectors. The basic idea is to extend

the estimation strategy to allow the inclusion of workers from non-tradables sectors in order to

further investigate the robustness of previous results. Thus, we will try to detect additional

effects on wage inequality that will be operating through shocks channeled by changes in nontradable labor demand. In order to do so, we extend equation (1) in the following way,

Log ( wijt ) dsijgt gt dsijgt m jt gm dt ijct ct f t (ageijt ) dsex ijt t ct j dsijgt nkt gk u ijt

g _1

g

c _1

g

k

To capture effects from changes in relative labor demand in non-tradable sectors we have

added KG interactions between the logarithmn of each nontradable sector share in total

GDP nkt and the three skill level dummies. The kt ‘s will give us these estimated effects.

Table 10 displays the results for Argentina.

29

(2)

Table 10: Coefficients (standard errors) of import penetration-skill and nontradable sectors share in total GDP-skill interaction on wages by skill group,

Argentina.

Variable

Coefficient

Standard

Error

0.0082

-0.0005

0.0608

0.0159

0.0190

0.0266

-0.0345

-0.0252

0.0179

-0.0069

-0.0016

-0.0425

0.0163

0.0192

0.0308

0.0213

0.0347

0.0330

**

-0.0359

0.0076

0.0465

0.0185

-0.0968

-0.0605

0.0203

0.0238

0.0335

0.0237

0.0373

0.0358

*

0.0269

0.0113

0.1826

0.0602

0.0725

0.2107

0.0277

0.0324

0.0418

0.0296

0.0438

0.0413

Import Penetration interactions

with low-skill

with semi-skill

with high-skill

**

Non Tradable sectors interactions

with low-skill

Electricity, Gas and Water

Construction

Wholesale & Retail Trade, Restaurants and Hotels

Transports and Comunications

Financial and Real Estate Intermediation

Other personal and social services

with semi-skill

Electricity, Gas and Water

Construction

Wholesale & Retail Trade, Restaurants and Hotels

Transports and Comunications

Financial and Real Estate Intermediation

Other personal and social services

***

*

with high-skill

Electricity, Gas and Water

Construction

Wholesale & Retail Trade, Restaurants and Hotels

Transports and Comunications

Financial and Real Estate Intermediation

Other personal and social services

***

**

*

***

Notes: *** if the coefficient is statistically different from zero at the one percent significance level. ** if the

coefficientis statistically different from zero at the five percent significance level. * if the coefficient is

statistically different from zero at the ten percent significance level.

We can see that after controlling by non-tradable sector relative demand shifts, the

coefficients on import penetration interactions are reduced. In fact only the high skillimport penetration interaction remains positive and significant.

30

Table 11: Coefficients (standard errors) of import penetration-skill and nontradable sectors share in total GDP-skill interaction on wages by skill group,

Uruguay.

Variable

Coefficient

Standard

Error

-0.0146

0.0037

-0.0033

0.0049

0.0047

0.0103

***

0.1415

0.2393

-0.1278

0.3545

0.2546

0.4882

0.0714

0.0425

-0.1297

0.0483

0.0624

0.0788

0.0553

0.0447

0.1182

0.0220

0.1267

0.2573

***

***

0.1547

0.2258

-0.1098

0.2270

0.2830

0.5208

0.0414

0.0208

-0.1303

0.0485

0.0625

0.0791

0.0544

0.0450

0.1182

0.0221

0.1265

0.2595

***

***

0.1612

0.2675

-0.0891

0.3667

0.2925

0.5386

-0.0024

0.0514

-0.1784

0.0499

0.0634

0.0798

0.0564

0.0466

0.1184

0.0234

0.1277

0.2596

***

***

Import Penetration interactions

with low-skill

with semi-skill

with high-skill

Non Tradable sectors interactions

with low-skill

Electricity, gas and water

Retail & Wholesale Trade and Hotels

Transport and Communications

Financial services and other servicies to the companies

Construction

Governmental services

Personal and Household sservices

Other Services 1

Other Services 2

***

***

***

***

with semi-skill

Electricity, gas and water

Retail & Wholesale Trade and Hotels

Transport and Communications

Financial services and other servicies to the companies

Construction

Governmental services

Personal and Household sservices

Other Services 1

Other Services 2

***

***

***

*

with high-skill

Electricity, gas and water

Retail & Wholesale Trade and Hotels

Transport and Communications

Financial services and other servicies to the companies

Construction

Governmental services

Personal and Household sservices

Other Services 1

Other Services 2

***

***

***

Notes: *** if the coefficient is statistically different from zero at the one percent significance level. ** if the

coefficientis statistically different from zero at the five percent significance level. * if the coefficient is statistically

different from zero at the ten percent significance level.

31

Still, in spite of the lack of significance of the low and semi skill interactions, previous

results are maintained: import penetration increases wage inequality by increasing the

wage premium of those workers with high skills.

The results coming from the non-tradable sectors interactions are also interesting. Note that

although not significant, coefficients on low skill interactions are negative, while those

associated with high skill interactions are positive and significant in several cases, having the

semi-skilled interactions mixed results. This suggests that relative demand shifts in

nontradables have had an inequalizing impact on wage distribution.

In the case of Uruguay (see Table 11), now appears a significant negative effect from importpenetration over low-skilled workers, indicating that after controlling for shocks in nontradable output structure, import penetration have had a positive impact on wage inequality.

Still, this result is not robust to the inclusion of cluster effects in the estimation. Finally, note

that non-tradable sector interactions do not generate substantial difference across different skill

levels, being the coefficients approximately the same across skill levels for each sector. We

conclude then that for the case of Uruguay we don’t find evidence that changes in sectoral

allocation of production and employment in services has had a significant effect on relative

wages.

As indicated previously the empirical model allows the estimation of time varying

dummies corresponding to the wage premium of semi and high skilled workers relative to

the low-skilled group. Figure 7 shows the results. The reported coefficients come from

the estimation that incorporates as control variables individual characteristics as well as

the import penetration and the changes in the GDP structure. We observe that, even after

controlling by these aspects, the tertiary wage premium rise during the ’90 in both

countries, while secondary (or medium skilled) wage premium remained pretty stable.

This dynamic of high-skilled relative wages has to be associated with other factors not

directly controlled for in the regression. One key candidate is biased technological

change. If this were the case we can conclude that in Argentina this determinant accounts

32

for an increase in almost 50 percent of the wage of college graduates compared to both

low and semi skilled workers. In the case of Uruguay, during 1991-1997, technological

changed could have implied a 20% increase in the wage of incomplete and complete

college workers relative to the other two skill categories.

Figure 7: Evolution of wage premium after control the estimation by import

penetration and change in the employment structure. Argentina and Uruguay

Argentina

1.4

1.2

1

0.8

0.6

0.4

0.2

0

1992

1993

1994

1995

1996

Tertiary wage premium

1997

1998

1999

secondary school wage premium

Uruguay

1

0.9

0.8

0.7

0.6

0.5

0.4

0.3

0.2

0.1

0

1987 1988 1989 1990 1991 1992 1993 1994 1995 1996 1997

tertiary wage premium

33

secondary wage premiuml

6. Concluding remarks.

In this paper we combine micro-data, taking from the various household surveys

and macro data, from national accounts, to investigate the effects of different shocks in

aggregate labor demand composition on relative wages. One question that we try to

answer is: does trade liberalization play any role in shaping the Argentine and Uruguay

wage structures during the period studied? In particular, we test whether those sectors

where import penetration deepened are, ceteris paribus, the sectors where a higher

increase in wage inequality has taken place. We find evidence that supports the

hypothesis tested for Argentina but that reject it for Uruguay.

Besides trade liberalization, in these countries there has a significant expansion in the

production and employment of non tradable output. This shift in production has had significant

effects on the relative demand of workers across skill levels. Thus in the empirical analysis we

also study whether changes in labor composition within the non-tradable sector have had

significant effects on relative wages. The results for Argentina suggest that relative demand

shifts in non-tradable have had an inequalizing impact on wage distribution. In the case of

Uruguay, results are less clear cut in the sense that the identify shock in labor demand in

services do not generates substantial difference across different skill levels.

Finally a large amount of research has sought to evaluate the effect of skilledbiased technological change in wage inequality. As most of the literature (cf. e.g.

Feenstra, 1998) we indirectly identify the magnitude of this determinant through a timing

variant dummy variable for the skill variable. We obtain that this factor explains a

significant portion of the increase in wage inequality after we control for individual

characteristics, sectoral dummies, trade liberalization and shock in the composition of

labor demand across nontradables.

34

References

Acemoglu, D. (2000) “Technical Change, Inequality, and the Labor Market”, Working

paper, NBER.

Arim, R y Zoppolo, G. “Remuneraciones relativas y desigualdad en el mercado de

trabajo”. Draft.

Berman, E., Bound, J. and Machin, S. (1998): “Implications of skilled-biased

technological change: International evidence”, Quarterly Journal of Economics, vol. 113,

pp. 1245-80.

Bernard, A., Bradford,J. (1998). “Understanding Increasing and Decreasing Wage

Inequality”, Working paper, NBER.

Bound, J., and Johnson, G. (1992): “Changes in the structure of wages in the 1980s: An

evaluation of alternative explanations”, American Economic Review, vol. 82, pp. 371-92.

Casacuberta, C y Vaillant, M. (2001) “Trade and jobs in Uruguay ‘90”. Draft.

Feenstra, R. (1998): “Integration of trade and disintegration of production in the global

economy”, Journal of Economic Perspectives, vol. 12, pp. 31-50.

Feenstra, R. (2000): The impact of international trade on wages, NBER, University of

Chicago Press.

Galiani, S. (1999): “The differential evolution of wages, job stability and

unemployment”, mimeo.

Galiani, S and Sanguinetti. (2000): “Wage Inequality and Trade Liberalization: Evidence

from Argentina”

Katz, L. and Murphy, M. (1992): “Changes in relative wages, 1963-1987: Supply and

demand factors”, Quarterly Journal of Economics, vol. 107, pp. 35-78.

Krugman, P. (2000): “An alternative model of trade, education and inequality”, in The

impact of international trade on wages, Feenstra, R. (ed.), NBER, University of Chicago

Press.

Kydland, F and Zarazaga, C.(1997: “Is the business cycle of the Argentina different?.

Economic Review, Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas.

Lawrence, R. and Slaughter, M. (1993): “Trade and US wages: Giant sucking sound or

small hiccup? Brookings Papers on Economic Activity, pp. 161-226.

35

Leamer, E. (1998): “In search of Stolper-Samuelson linkages between international trade

and lower wages”, in Imports, exports, and the American worker, Collins, S. (ed.),

Brookings Institution.

Richardson, J. (1995): “Income inequality and trade: How to think, what to conclude”,

Journal of Economic Perspectives, vol. 9, pp. 33-55.

Wood, A. (1995): “How trade hurt unskilled workers”, Journal of Economic

Perspectives, vol. 9, pp. 57-80.

36