liner notes for marty stuart's compadres

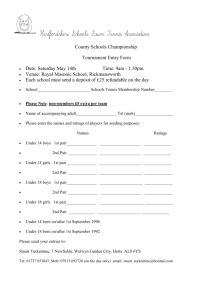

advertisement

MARTY STUART BIOGRAPHY

Marty Stuart was making the best music of his life in 2006. If you caught him in

Nashville in September, for example, you’d find him in front of his band, the Fabulous

Superlatives, a name that sounded less and less like hyperbole with each show. “Cousin”

Kenny Vaughan, on guitar, wore a white cowboy suit with cactus embroidery; “Brother”

Brian Glenn, on bass, wore a black jacket, bell-bottom jeans and white boots; and

“Handsome” Harry Stinson, on drums, sported a matching tan jacket and boots.

Out front, his hair rising improbably into the air, his black cowboy jacket outlined in

red piping, and his black-leather pants blending into his black boots, was Stuart himself,

picking his guitar and mandolin and singing with unprecedented authority. His show was

full of terrific original songs, but periodically he played a touchstone of country music

history, beginning with the bluegrass of “In the Pines," continuing through the

Bakersfield honky-tonk of “Buckaroo” and climaxing with the gospel original, “It’s Time

To Go Home."

As he shifted gears through all these styles and more, Stuart never lost momentum.

His stabbing mandolin notes and aching vocal evoked the desolation of the abandoned

lover in the pines; his jumping electric guitar captured the abandon of a Saturday-night

buckaroo, and his yearning drawl revealed the peace that can be found in accepting death.

Where did this new-found confidence and charisma come from? How, at age 48,

when many country-music veterans are slouching towards oblivion, has Stuart so

improbably reached new heights?

Unlike most show-biz success stories, he doesn’t claim the credit himself. He knows

his current achievement would never have been possible if he hadn’t walked every single

mile of the highway that got him here. And he never would have made it if not for the

mentors who showed the way and the partners who walked beside him. Those are his

“Compadres,” and his story can’t be told without them. Stuart realized as much when

John L. Smith, the researcher who compiled the Johnny Cash discography, started on one

for Stuart.

"When he started sending me session sheets," Stuart explains, “I started seeing all the

collaborations I had done and I realized how well they told my story. I strung them

together on a CD, let some fall by the wayside, and put the remainder on another CD.

What was left told the story of a young man's journey, starting with Lester Flatt and

arriving at the Fabulous Superlatives. It was the story of a kid who showed up with a

mandolin and a dream, became a guitar player in the Johnny Cash Band and became a

songwriter, an arranger and a producer. I look at it and see the unfolding of a life."

The journey began in Philadelphia, Mississippi, where Stuart’s father worked long

hours at the local factory. The only chance the young boy had for quality time with his

dad was Saturday afternoons when they’d sit down together to watch the syndicated

country-music shows on TV. Even on the family's small, black-and-white set, the stars’

costumes sparkled and dazzled, exerting a magnetic pull on a small-town kid with big

ambitions. And when little Marty finally saw one of those suits in person, the time Ernest

Tubb came to the Neshoba County Fair, it was, he says, “the most beautiful thing I’d ever

seen; it was as if my black-and-white TV were coming to life in full color.”

1

So when Stuart joined Lester Flatt & the Nashville Grass at age 13, his first ambition

was to play on the Grand Ole Opry and his second was to buy a suit like Tubb’s. He

played the Opry and then, on his first trip to California, he had the bus drop him off at

Nudie's Rodeo Tailors in North Hollywood on Lankershin Boulevard, “the street of badboy fashion." This was where everyone from Tubb to Elvis Presley went “shopping for

clothes," and the teenager had $250 of savings in his pocket.

“I tried on a suit," he remembers, “and asked how much it was. When Nudie [Cohen]

said, ‘$2,500,’ my heart sank through the floor. That sounded like more money than I’d

ever have. Just then I felt this presence come up behind me and it was Manuel Cuevas,

the same guy the older musicians had told me was the best tailor of all. He said, ‘Some

day, you’ll be able to buy every suit in here, but today you’re going to get a free shirt.’

He handed me a white shirt with red and blue flowers and said, ‘You’re my compadre.’

"I’d never heard the word before, but I soon found out what it meant. It meant he’d

always be there for me as an advisor, a friend, a brother, a kindred spirit, a soul mate,

someone who had my back. And he was. That’s why I’ve dedicated this album to him,

even though we’ve never played a note together. This album is a recognition that you

don’t get anywhere in life without help from your mentors and your peers—your

compadres.”

That’s true of everyone—whether one is a hillbilly star or a carpenter, a third

baseman or a math teacher. But many a star will try to convince you that he made it on

his own, a lone ranger finding his way in the wilderness without help or influence, a longmisunderstood genius finally recognized by the world. It’s always a good story, but it’s

never true. None of us succeed without teachers and teammates. Stuart is no different in

that regard; he’s just more honest about it.

A loquacious talker, he eagerly tells stories about Flatt, Cash and his other

compadres. A lifelong collector, he eagerly shows off the mementos he has gathered from

them. He still has the shirt that Cuevas gave him 34 years ago; he still has Flatt's ribbon

tie, Cash’s man-in-black suit, Pops Staples’ guitar and Merle Haggard's hand-scribbled

lyrics. And he still has the recordings that make up this album.

"I believe in ‘Honor Thy Father,’” he explains. “I got swept up in ‘Urban Cowboy’

movement, due to my age, but I saw no reason to turn my back on my history. To be

acknowledged by George Jones or Merle Haggard or Johnny Cash is something I’ve

never taken lightly. Those were graduation ceremonies. I always considered Lester as my

formal education and Cash as my finishing school. They were always my chiefs, but we

got to a point beyond boss and employee. We were compadres.”

Stuart spent the summer of 1972 playing mandolin with the Sullivan Family, an

Alabama bluegrass/gospel group. He was only 12, but he attended Pentecostal snakehandling services, George Wallace campaign rallies and bluegrass festivals.

"It was a summer of wearing cool clothes and long hair, of learning about girls, of

hanging out with cool people and get paid for doing so. I felt I had found my life. I felt

like I had run away with the circus. But when school started, I had to go back to the ninth

grade after experiencing all of that. It was horrible; I hated it. I didn’t fit in any more.”

So he leapt at an invitation from Roland White to play a show in Delaware with

Lester Flatt & the Nashville Grass. Stuart played the next date and the next, and pretty

soon he was a regular member of the band. Flatt was still rebounding from a painful split

with Earl Scruggs in 1969, but he had recently reconciled with his former boss, Bill

2

Monroe. Flatt's band often shared bills with Bill Monroe & the Blue Grass Boys on the

new, burgeoning bluegrass-festival circuit, and Monroe frequently found room on his bus

for the teenaged Stuart.

"It was like learning from an Indian chief," Stuart recalls. “He’d never say anything;

he’d just sit on the bus bench across from me and play a lick, and I’d play it back. When I

finally had ‘Rawhide’ down, he invited me out on stage. It got a big reaction every night.

Lester saw it and said, ‘We should do that in our show.’ ‘Rawhide’ became my showcase

number with the band and when we recorded the ‘Live! Bluegrass Festival’ album at

Vanderbilt University in 1974, that was on it. I’m including it here as a tribute to both

Bill and Lester.”

On the cover of the original album, the baby-faced, 15-year-old Stuart is standing to

Flatt’s right in a mop-top haircut and black cowboy hat, a head shorter than anyone else

on stage. The haircut reflected the changes blowing through bluegrass. The new

bluegrass-festival circuit was growing bigger each summer, and the music had been

discovered by “the Woodstock audience," as Stuart puts it. At a showcase for college

concert bookers, Lester Flatt & the Nashville Grass found themselves on the same bill as

Chick Corea and Kool & the Gang.

"Lester had just recorded ‘Feudin’ Banjos’ around the same time the film

‘Deliverance’ made the song famous,” Stuart says, “and when we did it live, the roof

came off the place. The next day we were rock stars with bookings at colleges all over the

country. There was no sense of tradition in the college audiences, but they were wild and

enthusiastic. We always did ‘Orange Blossom Special,’ and the more the kids screamed,

the faster the train got.

"But Lester never changed the set, and that was a life lesson for me. When I ran out

of commercial gas at the end of the ‘90s and had to chart a different course, I

remembered that lesson. It’s not always about changing and chasing. Sometimes it’s

about standing and staying who you are.”

Another date on that tour was at Michigan State, where the bill included Lester Flatt

& the Nashville Grass, the Eagles and Gram Parsons with Emmylou Harris. It was a night

that changed Stuart’s life, he claims. For the first time, he heard how traditional country

and rock'n'roll could be merged without compromising one or the other. It was a lesson

he would apply to his own solo records in the ‘90s.

"I didn’t even know who Gram was," Stuart remembers, “but I was drawn to him

because he was so unusual—this guy in a nudie suit and black fingernails, talking in a

fake cockney accent. We jammed backstage on old Louvin Brothers and George Jones

songs.

"Gram and the Byrds had the right idea, but their records didn’t sound like country

records. They couldn’t follow a Buck or Merle song on the radio. It took Brian Ahern,

Emmylou’s producer, to transform Gram's idea from black-and-white to Technicolor.

Just as George Martin took the Beatles’ Cavern sound and made it work on pop radio,

Brian took Gram’s country-rock sound and made it work on country radio. That's one

reason why I included ‘One Woman Man,’ which he produced."

When Flatt's declining health finally forced him off the road in 1978, Stuart and the

rest of the band played the already booked dates without him. It was during this time that

the youngster met Bob Dylan.

3

"Bob said, ‘How are Lester and Earl? Are they still friends?’” Stuart recalls. “Not

really. There are a lot of things unresolved.’ Bob said, ‘That’s sad. That’s what happened

to Abbott and Costello. They always said they were going to get back together but they

never did. And then the fat guy died.’ Dylan went on to do his show, and I went straight

to a pay phone and got Earl's phone number. I said, ‘Earl, this is Marty Stuart; I’d like to

meet you.’ ‘Come on,’ he said.

"When I got to his house, I said, ‘Lester's dying, and I know he’d want to say

goodbye to you.’ Earl said, ‘I heard he wasn’t feeling well.’ ‘No,’ I said, ‘he’s dying.

Here’s my number and here’s the room where Lester is.’ I went off with the band to

fulfill Lester's dates without him, but when we got back, Lance {Leroy, Lester's

manager} was standing there to meet the bus with tears in his eyes. ‘Earl visited Lester,’

was all he had to say. They were country boys with mountain pride, but they finally

overcame that pride. I knew they loved each other."

Stuart finally got to collaborate with the other half of the Flatt & Scruggs team when

Scruggs guested on Stuart’s second solo album, 1982's "Busy Bee Cafe." The final song

on the 2001 album, “Earl Scruggs and Friends," is an unaccompanied duet between

Scruggs’s banjo and Stuart’s guitar on the instrumental medley, “Foggy Mountain

Rock/Foggy Mountain Special."

But the performance that Stuart picked for this collection was the unaccompanied

mandolin-and-banjo version of “Mr. John Henry, Steel Driving Man” from Stuart’s

ambitious 1999 concept album, “The Pilgrim." The theme is familiar, but the variations

are not. The unorthodox digressions and the fleet-fingered tangents bear out Stuart’s

contention that the best bluegrass bands resemble jazz ensembles.

"There are some things that live inside of me," Stuart explains, “things that feel like

home. The sound of Earl’s banjo is one of those things. The sound of his banjo is part of

America; it's in the air we breathe. The first notes I heard on a record player came from

Flatt & Scruggs. It felt like family then; it feels like family now. The day we recorded

that track, it was a simple affair, just two microphones in the middle of the room. Earl

and Louise Scruggs, the engineer, and I were there and that was it. We recorded four or

five songs, but this was the one with the magic in it."

Though Stuart is best known for his electric-guitar country recordings, bluegrass has

been an unbroken thread through his career. From his first tour with the Sullivan Family

in 1972 to “Live at the Ryman," his remarkable bluegrass album with the Fabulous

Superlatives in 2006, string-band music has been a constant in Stuart’s life. And he

rejects the conventional wisdom that the best days of bluegrass are in its past.

He cites the Del McCoury Band, Alison Krauss & Union Station and Ricky Skaggs

& Kentucky Thunder as contemporary examples of the music at its best, and he submits

“Let Us Travel, Travel On," his collaboration with the McCoury Band, as evidence. The

track comes from the 2003 tribute album, “Livin’ Lovin’ Losin’: Songs of the Louvin

Brothers," with Stuart singing Charlie Louvin's part and McCoury singing Ira Louvin’s

part.

“Some people tend to water it down the more successful they become," Stuart says,

“but the more successful Del gets the more he strips it down to the real thing and that's

what makes him great. He's an encyclopedia on the music of Bill Monroe and Flatt &

Scruggs, and he’s glad to talk about it. When I play with that band I never have to think

4

about anything, because it's already taken care of. I feel like I’m among master

craftsmen.”

After brief stints with Vassar Clements and Doc Watson in the wake of Flatt's death,

Stuart landed the job he’d always wanted: playing in the Johnny Cash Show. The first

three albums Stuart had ever owned were ‘The Fabulous Johnny Cash,’ ‘Flatt & Scruggs’

Greatest Hits’ and ‘Meet the Beatles.’ He’d already played with Lester Flatt and he had

long ago traded in the Beatles album for more country records. Cash, Stuart knew, was

the professor who could complete his education.

"Johnny Cash's records had once transported me from my bedroom in Philadelphia,

Mississippi, to the rest of the universe," Stuart explains, “so I’d always wanted to meet

him. When I finally did, there was an immediate connection. ‘Where’ve you been?’ he

asked me. I told him, ‘Getting ready.’ And he said, ‘OK, let's go.’”

Away they went, down the road for six years of tours that included June Carter, the

Carter Family, and the Tennessee Three. Stuart even married Johnny’s daughter Cindy

Cash for several years, joining a collection of sons-in-law that eventually included

Rodney Crowell, Nick Lowe, and Jack Routh. They all became ex-sons-in-law, yet Cash

not only remained a friend but also recorded songs by all of them.

"At one point he was my father-in-law and at another point he was my ex-father-inlaw,” Stuart says, “but we never let that get in the way of the music. He was a mentor to

me. He became my next-door neighbor later in life. When my own career took off, I went

to him countless times as an advisor and trusted friend.

"The last time I hung out with Johnny Cash was four days before he died. I had just

recorded ‘The Walls of a Prison’ for the ‘Country Music’ album, and I played it for him.

I was sitting at his feet, and when it was done, he opened his eyes and said, ‘Excellent,

my son. I never heard you sing like this before.’ ‘I never felt this way before,’ I said. I

felt a sense of completion that day. I’d quit chasing, quit worrying about it. I stopped

looking at the charts and just started doing. I let my heart speak, and that's the greatest

lesson I took from Johnny Cash.”

Cash sang with Stuart on “Busy Bee Café” and on the Nashville Grass version of

“Mother Maybelle,” but it wasn’t until Stuart had some success of his own under his belt

that he could finally engage his former employer as something of an equal. The album

was Stuart’s 1992 “This One's Gonna Hurt You," and the song was “Doin’ My Time," a

prison number written by Jimmie Skinner and recorded by Flatt & Scruggs, Bill Monroe,

David Grisman and the New Grass Revival. Cash had cut it for Sun Records, had often

sung it on stage with Stuart and revived his clickety-clack railroad rhythm for this track.

Cash's baritone rumbles like a locomotive engine; Stuart's voice calls like a train whistle,

and the arrangement's pell-mell momentum suggests the way temptation leads to crime,

crime leads to prison and prison leads to remorse.

After six-plus years with Cash, Stuart realized you can’t stay in school forever; at a

certain point you have to leave the classroom and apply the lessons you’ve learned. His

first two albums had been largely acoustic projects on small bluegrass labels, but his third

album, “Marty Stuart," was a big-budget, country-rock effort on Columbia Records,

aimed square at the charts, and it deserved a supporting tour. So, with some reluctance,

he resigned from the Johnny Cash Show, pulled together his own band and hit the road. It

worked, to an extent. The first single, “Arlene," snuck into the Top Twenty, and the

second, “All Because of You," snuck into the Top Forty.

5

Stuart has some regrets today about the synthesizers and some of the songwriting on

that album, but the disc did crackle with the 22-year-old singer's infectious mix of livewire rockabilly energy and hard-country roots. As a result, music journalists grouped

Stuart with four more country artists—Steve Earle, Dwight Yoakam, Lyle Lovett, and

Randy Travis—who also emerged that year with records that reached back to older music

yet sounded paradoxically fresher than most of country radio. Each of the five singers put

multiple singles into the Country Top Forty. They were called “The Class of 1986."

"When I first started making records at Columbia,” Stuart remembers, “three names

began to represent a new movement in country music—Steve, Dwight and me. We were

the three new kids on the block that people wanted to watch, because we had a kind of

legitimacy about us after the Urban Cowboy craze. So I first saw Steve on the pages of

magazines. When I met him, I loved him because he was so serious about his craft. We

became buddies; we had a lot of the same heroes, a lot of the same demons, a lot of the

same struggles.

"The pendulum had swung back from the glossy, glitzy ‘Urban Cowboy’ sound to

something rootsier. We were closer to the source. A magazine did a photo spread of

young stars with their mentors, and they shot me with Johnny Cash. There was a torch

being passed. We were inspired by a tradition, but we weren’t imitating it. It’s not about

following the parade; it was about leading the parade. It was a vote of confidence to line

up alongside these people.”

“The Class of 1986” was a moment of great possibility. For a brief instant, it seemed

as if the narrow gates of country radio might swing open and allow a gutsier, rootsier

brand of country music to go out over the airwaves. Before long, though, the gates closed

tight again. By that time, Yoakam and Travis were safely inside, but Stuart, Earle, and

Lovett were left outside. By 1988, none of the three could be heard on country radio.

Lovett didn’t feel comfortable at country radio, and asked MCA to transfer his

contract to the pop division. Earle’s struggles with drug abuse alienated him from Music

Row and eventually landed him in prison. Stuart thought he’d take advantage of his

initial breakthrough to make the album he really wanted to make, a session that would

revive the hard-hitting honky-tonk of Bakersfield. That’s not what Columbia was looking

for and the label refused to release “Let There Be Country.” Both sides dug in their heels,

and Columbia wouldn’t release “Let There Be Country” till 1992, after Stuart had moved

on to MCA and racked up a bunch of hits.

In the meantime, Stuart was scuffling, unwilling to go back to being a sideman,

unable to give up on his dream of being a bandleader, looking for a record company that

might share that dream. In one of his darkest moments, when he was unsure whether he

should keep trying, Stuart was walking behind Columbia Records when a long car pulled

up and the rear window slid down. Out popped the head of none other than George Jones,

who asked, “What are you moping for? Don’t let them get you down.” The window slid

back up, and the car rolled away. It was a funny incident, but it gave Stuart the shot of

encouragement he needed. Hell, if George Jones believed in him, why shouldn’t he

believe in himself?

The Possum proved that he meant it by inviting Stuart to join Jones’s 1991 album of

duets, “The Bradley Barn Sessions." The song was “(I’m a) One Woman Man," which

had been a #7 hit for songwriter Johnny Horton in 1956 and a #5 hit for Jones himself in

1989. It was also a highlight of Stuart’s “Let There Be Country” album, which should

6

have been released in 1987. The shift from Stuart’s warble to Jones’s bottomless baritone

reinforces the recording’s gravity-free sense of falling in love.

"An intense blizzard hit Nashville while we were recording,” Stuart recalls, “and

knocked out the power everywhere but Bradley's Barn. So all these rock and country

luminaries gathered there and made music with George Jones. Keith Richards was pacing

in the hall outside; he was very nervous because he was a huge George Jones fan.

Meanwhile, George was nervous because he didn’t know who Keith was. George asked

me, ‘What's the name of that boy that came to play?’ I told him. ‘What's that bunch he

plays with?’ ‘The Rolling Stones,’ I said. ‘Are they hot?’ he asked. ‘Yeah,’ I said, ‘pretty

damn hot.’”

Stuart launched his comeback on his new label, MCA, with the 1989 album,

“Hillbilly Rock," produced by the Steve Earle team of Richard Bennett and Tony Brown.

The title track, which became a Top Ten single, summed up Stuart’s new approach: “Beat

it with a drum; playing the guitars like shooting from a gun, keeping up the rhythm,

steady as a clock; doing a little thing called the hillbilly rock.” This was hillbilly music:

songs about small-town girls, restless wives, hard-working husbands, and rural outlaws,

delivered with a twang of the guitar and a drawl of the voice.

The difference was the drums. Drums had always been implied in bluegrass and

buried in honky-tonk, but now they were brought out front along with the rhythm guitar

and bass. This was country music with an irrepressible optimism and a franker sexuality,

a combination perfect for a 25-year-old single guy just coming into his own. The next

album, 1991’s “Tempted,” used that approach to put four more singles (“Little Things,"

“Till I Found You," “Burn Me Down," and the title track) into the Top Twelve. Fueled by

success, Stuart started writing songs as fast as he could come up with them, often with a

new circle of compadres.

One of the most oft-heard phrases in Nashville is “Hey, let’s get together and write a

song.” One of the many partners that Stuart co-wrote with was Ronnie Scaife, and they

came up with “The Whiskey Ain’t Workin’." Stuart didn’t need the song, because he’d

just released “Tempted” and wouldn’t start another album for many months. So they sent

it to Hank Williams Jr., but he passed. Then, one day while Stuart was at a drive-in

burger joint in Birmingham, he heard the radio play “Country Club” by a young singer

named Travis Tritt. Stuart was so impressed that he decided to send a demo of “Whiskey”

to the newcomer. Not only did Tritt want to record the song, but he wanted Stuart to

recreate the guitar part he’d put on the demo.

"I had finished the guitar part and was walking out of the studio," Stuart relates,

“when the producer, Gregg Brown, called me back in and said, ‘Sing the second verse;

maybe we’ll turn it into a duet.’ The next thing I know it’s not only a duet but also a hit

on country radio. I still hadn’t spoken with Travis, so I went up to him at Fan Fair and

introduced myself. He said, ‘Why don’t you come on out on stage and sing it with me?’

The crowd went nuts, so we decided to make a video for the song. At the end of the

filming, we shook hands and hugged, and I said to him, ‘When we’re old and fat and bald

and ugly and nobody cares anymore, I’ll still be your brother.’ And that's the way it’s

been."

“The Whiskey Ain’t Workin’” became a #2 smash, and it was followed by such

duets as 1992's #7 hit, “This One's Gonna Hurt You (For a Long, Long Time)," and

1996's #23 hit, “Honky Tonkin’s What I Do Best." The friendship implied in many

7

country duets is often an on-stage act more than an off-stage reality, but Tritt and Stuart

forged a real bond. In 1992, they hit the road on the “No Hats Tour,” an irreverent rebuke

to the many “hat acts” dominating Nashville at that time. Stuart contributed songwriting

to Tritt's next three albums (“t-r-o-u-b-l-e,” “Ten Feet Tall and Bulletproof” and “The

Restless Kind”), played guitar on two of them and sang a duet vocal on “Double Trouble”

from the last one.

Meanwhile, Stuart continued to rack up hits of his own. The 1992 album, “This

One's Gonna Hurt You," yielded not only the title-track duet with Tritt but also three

other Top Forty singles: “Now That's Country,” “High on a Mountain Top," and “Hey

Baby." Things started to slow down with the 1994 album, “Love and Luck," and the 1996

disc, “Honky Tonkin’s What I Do Best." It was at that time that MCA decided to make

the tribute album, “Not Fade Away (Remembering Buddy Holly),” and it made sense to

include the singer of “Hillbilly Rock." But Stuart insisted that he record with one of his

old compadres, Steve Earle.

"Steve had just gotten out of prison, and the record company didn’t want anything to

do with him," Stuart recalls, “but I said I wouldn’t do it without him. Richard Bennett,

who had produced both Steve and I, was the coordinator for my track on the Holly album,

and he helped make it happen. I was never so happy to see someone back in my life as I

was to see Steve, because I’d thought we’d lost him. The first time I heard Steve sing

‘Guitar Town’ back in 1986, I believed I’d heard the future of country music. I still

believe that."

Stuart and Earle teamed up on Holly's 1958 song, “Crying, Waiting, Hoping." The

bluesy slide guitar at the beginning is just something Stuart was fooling around with in

the studio that the ever-alert Bennett captured by pushing the record button. The song

itself gets its delicious tension from the contrast between Earle's “Crying, Waiting” low

tenor and Stuart’s “Hoping” high tenor, between Earle’s chunky rock guitar and Stuart’s

trilling slide. When Stuart received a Lifetime Achievement Award from the Americana

Music Association at the Ryman Auditorium in 2005, Earle was the presenter and

publicly thanked Stuart for giving him his first paycheck after prison, his first chance to

get back in a recording studio.

Stuart owed MCA one more album on his contract, and he decided that instead of

chasing after elusive radio airplay he was going to make the record he’d always wanted

to make. Although he had written skillfully and knowingly for Country Music Magazine

and other publications, his song lyrics had largely stuck to simple radio fare. Although he

was president of the Country Music Foundation and had assembled one of the world’s

foremost private collections of country-music artifacts, he seldom let that history seep

into his own songs. Now he would.

“In truth,” he admitted at the time, “on the last couple albums, I was trying to be a

good little artist and color inside the lines. I liked the music, but it wasn’t coming from

the depths of me and after a while it wasn’t selling that great. About three years ago, I

said, `I’m done compromising; I want to do something that's really me.’ Change was

inevitable. There were two options: I could chase radio again and die a horrible death. Or

I could walk to my death honorably."

The result was a concept album entitled “The Pilgrim,” Based on a true story from

Stuart's Mississippi hometown, the songs describe a title character who falls in love with

a woman at work, discovers too late she's married, watches her husband kill himself, flees

8

the town for years of drunken wandering, and finally finds redemption in religion and

marriage. Here are the great themes of hillbilly music—infidelity, violence, rambling,

alcoholism, church and family—wrapped up in an ongoing narrative.

To give that story the scope it deserved, Stuart employed the full range of country

music, from the cranked-up, drum-driven country-rock of his recent records to the

bluegrass and honky-tonk of his work with Lester Flatt and Johnny Cash, from old-time

mountain songs and Western swing to countrypolitan. To help him pull it off, Stuart

called on his compadres: Cash, Ralph Stanley, Emmylou Harris, Earl Scruggs, George

Jones and Pam Tillis. The Scruggs collaboration is included on “Compadres” but any of

them could have been.

“I have enough styles of music under my belt to do it,” Stuart said in 1999, “and

enough numbers in my phone book to make it happen. I knew I had to do it now, because

I’ve gone to too many funerals for the old-timers over the past 10 years. Plus it's the end

of the century, the first century of country music, and I wanted to sum up.”

“The Pilgrim” was critically hailed as the highlight of Stuart’s career, but radio

ignored it, and it would be four years before he released another album. He was dropped

from the MCA roster, but at least he was in good company.

"In the late ‘80s, MCA had the strongest roster of country music acts since Columbia

had Cash, Flatt & Scruggs, Johnny Horton, Lefty Frizzell, Ray Price and Marty Robbins

in the late ‘50s. MCA had George Strait, Steve Earle, Lyle Lovett, Marty Stuart, Patty

Loveless, Reba McEntire, the Mavericks, Vince Gill, and Trisha Yearwood. It was an

awesome time of creative freedom, but MCA let most of it get away from them.

"I still believe that given the opportunity, the masses will respond to the real thing.

The chink in country music’s armor is in its identity crisis. When it chases pop trends,

when it dresses up and tries to go to town, it loses its power, its authenticity. It always

enjoys a surge of success when it tries to cross over, but it soon sounds like everything

else and that success evaporates into nothing.”

In 1998, Music Row made a gesture in the direction of tradition by organizing an

album of contemporary stars such as the Dixie Chicks and Randy Travis singing songs by

the likes of Tammy Wynette and Merle Haggard. Stuart was asked to come up with a

new song that would tie all the tracks together into a unifying theme.

"I thought, ‘Let's go back to the getting-on place, to the station where country music

got on the train of American culture,’" he recalls. “’Let’s go back to Bristol, to the place

where the Carter Family and Jimmie Rodgers made history. Let’s make a story out of

that.’ I wrote the first verse and threw it away. Connie {Smith, his wife} literally pulled it

out of the trash can, smoothed it out on the table, and said, ‘Don’t throw this away; it's

too good.’ So I went back to Merle's tribute to Jimmie Rodgers, ‘Same Train, Different

Time,’ and I turned that title into a story. I asked Merle if he’d mind, and he said, ‘No,

just let me sing on it.’”

Merle wasn’t the only compadre to join Stuart on “Same Old Train," released on

the 1998 album, “Tribute to Tradition.” Dwight Yoakam and Randy Travis from the

“Class of 1986” also joined as did such contemporaries as Travis Tritt, Patty Loveless,

Pam Tillis, Alison Krauss, and Ricky Skaggs and such allies as Earl Scruggs and

Emmylou Harris.

"Emmylou was a godmother to all of us who were looking to go a different way,"

Stuart acknowledges. “From the first time I saw her with Gram at Michigan State, it was

9

obvious she was a rock star with a folk musician's heart. Every time I get the guts to try

to make a new musical path, I find she's already been there. She had a lot to do with

crashing the door open for the ‘Class of 1986.’ ‘Blue Kentucky Girl’ and ‘Roses in the

Snow’ made it OK for roots because they’d been done by her. That's why I call her

‘Queenie.’"

A few years earlier, Music Row had organized a similar multi-artist collection.

Instead of trying to illustrate the connection between old and new, “Rhythm, Country &

Blues” illustrated the often overlooked links between country and R&B. To shine some

light on those ties, Vince Gill and Gladys Knight sang the R&B hit “Ain’t Nothing Like

the Real Thing," while Al Green and Lyle Lovett sang the country hit, “Ain’t It Funny

How Time Slips Away." At his own request, Stuart was paired with the Staple Singers on

the Band's “The Weight."

"I had never heard of or seen the Staple Singers till 1978 when I saw ‘The Last

Waltz,’” Stuart admits. “But when the camera in that movie panned to Pops Staples, I

thought it was Moses. Then I heard him sing and knew I was right. I went out and bought

all the Staples Singers records I could find. Then I finally met them. Just like with Johnny

Cash and Travis Tritt, the first time I met Pops it was like, ‘Where’ve you been all my

life? Let’s get going.’ In all these instances, it was music that led to everything else.”

Stuart's hometown, Philadelphia, Mississippi, became a symbol of segregation

throughout the world when three Civil Rights workers were brutally murdered there in

1964. Tensions within the town itself were as tight a new barbed wire. It was a long time

before Stuart could hang out again with Virgil Ivy Griffith down at the Busy Bee Café.

Griffith taught school during the week and led an R&B dance band at juke joints on

weekends. He turned the young Stuart onto R&B records, and Stuart turned him on to

country records. So, from an early age Stuart realized just how much the two musics had

in common.

"If you put ‘Rocky Road Blues’ and ‘Got My Mojo Working’ nose-to-nose,” he

insists, “there ain’t a nickel's worth of difference between them. They both have that train

rhythm. If you think of the influence of Leslie Riddle on A.P. Carter, of Tee Tot on Hank

Williams, and of Arnold Schultz on Bill Monroe, you know that African-American music

has always been part of country music. I was talking to Sam Moore {of the R&B duo

Sam & Dave} about the Staples once, and he referred to them as a bluegrass band.

"The Staples Singers told me that they always listened to country music going down

the road. I said, ‘That’s funny because I always listened to the blues.’ Country music is

the white man's blues. To be a blue-collar white guy in the South was not a whole lot

different from being a struggling black person in the South. Hate was a commodity that

politicians could sell, and as long as people could be turned that way, they could be

controlled. But to me it’s more of a stretch to get away from the black influence in

country music than to stay with it. The older I get and the deeper I get into it, the more I

emphasize that connection.”

After that first collaboration with the Staples, Stuart stayed in close contact with the

family. When both Stuart and Pops Staples were inducted into the Mississippi Music Hall

of Fame in 2001, the ceremony was held in the Mississippi State Capitol in Jackson, a

building that Staples couldn’t have entered as a young man in the days of segregation. On

this morning, though, he not only entered but commanded the attention of the Mississippi

10

Senate. He asked everyone to stand and hold hands, and while Stuart played the guitar,

Staples led everyone in ‘Will the Circle Be Unbroken.’”

"If I could take one day with me to heaven,” Stuart declares, “it would be that day.

When I heard Pops leading the Mississippi Senate in song, I knew something had

changed forever. After Lester was gone and when Cash was unavailable, I never made a

move without calling Pops and discussing it with him. When Mavis and Yvonne Staples

gave me Pops’ guitar after he died, I felt like I’d been bequeathed Excalibur, a mighty

instrument of light.”

Mavis joined Stuart and the Fabulous Superlatives on Stuart’s 2005 gospel album,

“Souls’ Chapel,” for a song that Pops wrote, “Move Along Train." As Stuart and Mavis

toss the melody back and forth, they generate the musical momentum that will carry “the

gospel train” with its “heavy load … safely home."

"Singing with Mavis is like singing with Mother Earth," Stuart marvels. “She sings

from such a been-there, done-that place. She embodies so many people when she sings,

because she had to sing on behalf of a struggling race that needed to have their voices

heard. She must be one of God's favorite singers."

Stuart met B.B. King at the Grammies one year, and quickly realized how much they

had in common. They were both country boys from Mississippi and both loved a wide

swath of music. So when King decided to record an album of duets, “Deuces Wild," in

1997, he invited Stuart to be a duet partner alongside Eric Clapton, Van Morrison,

Bonnie Raitt, and the Rolling Stones. The song was “Confessin’ the Blues,” the 1941 Jay

McShann hit. The two men trade verses and guitar licks as if they’re having the time of

their lives.

"I had always loved B.B.’s tone, because it sounded like he was plugging into the

earth," Stuart says of the sessions. “So I asked him, ‘What kind of amp do you use?’ He

said, ‘I don’t know.’ That’s when I realized that tone comes from the player, not the

equipment.”

It took Stuart several years to recover from the disappointing sales of “The Pilgrim,”

his best record of the 20th century. By 2002, however, the musical itch was bothering him

so much that he had to scratch it. He decided to put together a new band, and the first

person he called was Kenny Vaughan.

"I first heard Kenny Vaughan on the ‘Austin City Limits’ TV show with Lucinda

Williams," Stuart explains. “After a few measures, I got so fascinated with Kenny that I

forgot to watch Lucinda. I always liked guitarists like Luther Perkins or Don Rich, Joe

Maphis or Roy Nichols, who were the stars of the show for certain listeners. There aren’t

many guitar slingers like that left, but when I saw Kenny on TV, I said, ‘He’s got it.’”

The second person Stuart called was Harry Stinson, who had been a crucial part of

Steve Earle’s earliest records and of Stuart’s biggest hit singles. Stinson was not only a

solid drummer but also a terrific harmony singer and arranger. Vaughan suggested that

bassist Brian Glenn audition and from the minute the four men played their first song

together, the line-up was set.

"I basically shut down the auditions, locked the doors and went to work," says Stuart

of that first song. “I immediately knew it was the band of a lifetime; there was nothing I

threw at them that they couldn’t handle.”

The Fabulous Superlatives have now released four albums. The 2003 , “Country

Music,” lived up to its title by demonstrating a command of every sub-genre that might

11

possibly fit under the country-music umbrella. The two 2005 albums, “Souls’ Chapel”

and “Badlands," were organized around themes, gospel music and American Indian

songs, respectively. And the 2006 release, “Live at the Ryman," showcased the group's

bluegrass side. On all four titles, there’s an unmistakable push-and-pull of a real band

where each member stakes out his own ground.

"It’s a matter of perspective," Stuart comments. “A lot of people prefer someone up

front singing with hired musicians behind them. The world is full of that. I prefer to be

part of a band. It's that ‘compadre’ thing. When people have asked me why I gave up so

much of the spotlight on ‘Souls’ Chapel,’ I said, ‘I don’t see it that way. When Paul

Warren played a fiddle solo, it didn’t diminish Lester Flatt’s spotlight; it enhanced it.

When Anita Carter sang on the Johnny Cash Show it didn’t detract from Johnny Cash; it

helped him. When I let Harry or Kenny or Brian loose, it doesn’t detract from me; it

helps me."

Of all the compadres in Stuart’s life, none means more than his wife, Connie Smith.

Her 1966 album, “Miss Smith Goes to Nashville,” was a favorite album of Stuart’s

mother, and as a young boy he would stare at the album cover, mesmerized by a

photograph as captivating as the music. When he was 12, he heard Smith at the Choctaw

Indian Fair in Philadelphia, Mississippi, and the spellbound youngster got the singer's

autograph and had his picture taken with her. On the way home he told his mother that he

was going to marry her some day. Twenty-five years later he did.

"In 1994, Connie came to my dressing room at the Grand Ole Opry and said she was

thinking about making a record," Stuart continues. “She asked if I would produce it, and I

said, 'Absolutely.' She hadn’t made a record in 21 years, because after making 50-some

records early in her career, she had called a time-out that stretched on and on.

"At the time we were acquaintances but not close friends. I knew she could sing

beautifully but I suggested she might want to write the songs for her next album. I called

Harlan Howard and the three of us wrote a country shuffle called ‘How Long.’ I call it

our first date, because there’s nothing like a good country shuffle to kick off a

relationship. Then we wrote 'Hearts Like Ours,' and, well, you know how it is: you start

writing love songs for one another and pretty soon you’re living the songs."

“Hearts Like Ours” was a highlight when the album was eventually released by

Warner Bros. in 1998 as “Connie Smith." She sang it by herself, but because the song

was so important to the couple’s 1997 marriage, Stuart decided to add a duet vocal to the

track for the “Compadres” album. Even if you didn’t know the two singers were married,

this ballad would let you know that something was going on between them.

"Constance is the most reluctant superstar I’ve ever known," Stuart points out. “Her

treasure has always been her family, not her accolades. That’s why she took all that time

off; she was dedicated to seeing to her kids. And she has a wonderful family to show for

it. She’s well versed in the art of home, whereas I’m well versed in the art of career.

Because of that, Connie's a good balance for me, because I’m a career-driven maniac.

"Loretta is my wife's favorite singer,” Stuart adds, “so she lives in the atmosphere of

our house. Lately, I’ve also lived with Loretta on our bus, because we’ve been watching

her on videos of the Wilburn Brothers’ show from the mid-‘60s. I’m always amazed by

how spot-on she is as a singer. Unlike the other people on this record, Loretta was

someone I’d admired from afar rather than knowing as a friend. When we recorded the

12

track, it was the first time we’d ever sung together, but when we did, it was so easy, it felt

as if we were family."

Stuart chose “Will You Visit Me on Sunday” for their duet, because he’d always

wanted to record a Dallas Frazier song. After all Stuart's wife has recorded 68 Frazier

songs, and this was a 1968 hit for Charlie Louvin. In this new version, Stuart sings the

role of a death-row prisoner torn between his impending doom and his final Sunday visit

with his darling wife. Lynn sings the role of the wife torn in similar ways between the

horror of execution and the relief of one last embrace.

"Next to Hank Williams,” Stuart argues, “Dallas Frazier may be the best songwriter

in country-music history. I go through his catalogue and keep saying, ‘I didn’t know he

wrote that; that's a great song.’ A lot of songs you can take apart and change this chord or

that line, but you can’t do that with his songs because they are that rock solid."

In 2003, Stuart came up with the idea for an Electric Barnyard Tour of small

American towns that are usually bypassed by big country tours. He wanted to travel the

back roads and play for “the forgotten people," as Merle Haggard calls them. The tour

featured Stuart with his Fabulous Superlatives, his wife Connie Smith, BR-549, Rhonda

Vincent, the Old Crow Medicine Show and Haggard himself. The tour would pass

through neglected towns such as Hutchinson, Kansas, and Tuscumbia, Alabama, but also

towns like Tulare, California, and Saginaw, Michigan, that are associated with famous

country songs.

"In scoring films, I learned that the music should line up with the visuals," Stuart

explains. “When I drive the back roads of any state in the union, I see people still riding

tractors and still hanging their laundry out on the line. When I play traditional country

music or bluegrass in those places, the audio and the visual line up perfectly. But when I

listen to the Country Music Meltdown in those places, the audio doesn’t fit the visuals.”

Stuart wanted to climax each show with a duet between himself and Haggard, but he

needed to find just the right song. It was “Farmer's Blues,” a rural lament that he had cowritten with his wife. It felt right. Both of Stuart’s grandfathers had been farmers, and as

the “poet of the common man,” Haggard was drawn to the subject.

"I met Merle in Louisville before the tour," Stuart recalls, “and said, ‘I’ve got the

song.’ Merle said tell me about it.’ So I sang the first verse: ‘Who’ll buy my wheat?

Who’ll buy my corn to feed my babies when they’re born? Seeds and dirt, a prayer for

rain that I can use. I walk the land; I watch the sky and wonder why, but it's the only life

I’ve known, these farmer's blues.’ Merle said, ‘Change one word. Instead of ‘I walk the

land,’ say, ‘I work the land.’’ I did and we sang it every night."

Another act on the Electric Barnyard Tour, the Old Crow Medicine Show, has led the

recent revival of old-time string-band music. A quintet of kids in their 20s, all of whom

played in rock bands at one point, Old Crow recalls the era in the 1920s and ‘30s when

mountain bandleaders such as Gid Tanner and Riley Puckett attacked their fiddles and

banjos with the reckless ferocity of punk-rockers in the 1970s.

Stuart highlights that connection by having Old Crow and the Fabulous Superlatives

(featuring former punk-rocker Kenny Vaughan) play the Who’s 1967 rock'n'roll hit, “I

Can See for Miles," on acoustic instruments. The surging power of Vaughan's acoustic

guitar, Ketch Secor's fiddle, and Willie Watson's guitar demonstrate that the real energy

in music comes not from electricity but from a musician's soul.

13

"I saw the Old Crow Medicine Show for the first time at the Uncle Dave Macon

Days Old Time Music Festival in Murfreesboro," Stuart remembers. “They were playing

this high-energy, old-time music with their guitar cases open for tips. I liked them so

much that I brought them down to the Ryman and had them play on the Grand Ole Opry.

They got a big ovation, but then I couldn’t find them. When I finally tracked them down,

they’d gone out to the front of the Ryman and they were busking again.”

This album demonstrates not only the art of collaboration but also the value of

apprenticeship. But when you work closely with a mentor—as Stuart has with Lester

Flatt, Johnny Cash, Pops Staples, and others—you inherit not just a body of knowledge

but an obligation as well—an obligation to pass that knowledge on to the next link in the

chain. Stuart is doing that with the Fabulous Superlatives, the Old Crow Medicine Show,

and as many others as he can reach.

"When I see a kid standing in front of the stage with that look like he’s really getting

it, I know I have a responsibility to pass it on to him like Lester passed it on to me. About

two years ago, for example, I spotted this little kid in the autograph line at a show near

Bristol, Tennessee. His name was Trey Hensley; he was 11 years old with braces. But

when I asked him to play something, he played a Maybelle Carter riff perfectly. That

inspired me to invite Trey and Earl Scruggs to one of my shows at the Opry. It was one of

those nights where it all lined up, where you could see the tradition being passed from

generation to generation to generation.”

Back at his office in Hendersonville, Stuart holds up a hefty red cube in his right

hand and waves it about. “This is what I want," he declares. The cube is the cloth-bound

box set, “The Complete Ella Fitzgerald Songbooks," a handsome package of the jazz

singer's classic interpretations of the great mid-century songwriters, accompanied by a

thick booklet. Stuart says he wants to sum up his own, many-faceted career with a box set

just as ambitious and just as handsome. Someday, he hopes, “Compadres” will be one

disc in that box set, because he could never sum up his career without the characters on

this album.

"The people on ‘Compadres’ come from a wildcat America, a less tamed America,"

Stuart argues. “Pops Staples, Steve Earle, Earl Scruggs, B.B. King, these are the kind of

people who made America a more interesting place—sonically, visually, spiritually.

Those are the people I wanted to emulate as a kid, those are the people I ended up

traveling with. I like to think I ended up one of them. They didn’t represent a simpler

time; their times were just as complex as ours. And they brought that complexity to their

music; they brought their sweat, their soul, their lives.”

"Edward S. Curtis called the Indians he photographed in the early 20th century ‘the

vanishing race,’ and I call this era of country music ‘the vanishing race.’ Singing with

Johnny Cash is like singing with Sitting Bull. Singing with Merle Haggard is like singing

with Geronimo. Just as Curtis documented his chiefs with film, ‘Compadres’ documents

my chief with tape .

"When I listen back to all these recordings, I think of that line I wrote in ‘The

Pilgrim’: ‘What a journey I have known.’”

14