Partisan and Nonpartisan Election Administration

advertisement

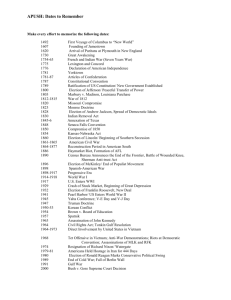

Partisan and Nonpartisan Election Administration 1 Daniel P. Tokaji The Ohio State University, Moritz College of Law Prepared for Election Reform Agenda Conference University of Iowa May 7-9, 2009 2 Please don’t cite without permission Draft - 5/4/09 The significant discretion vested in those who run our elections makes it imperative that they discharge their duties in an evenhanded manner. Since the contested 2000 presidential election that inaugurated the recent wave of election administration reforms,1 the partisanship of state and local election officials has been a prominent subject of concern. The actions of Florida’s Secretary of State Katherine Harris, who was co-chair of the Bush-Cheney’s 2000 campaign in Florida, caused enormous consternation in Democratic quarters. There was also concern about the actions of officials at the local level, many of whom were elected on a partisan basis. These concerns reappeared in the 2004 election, when the spotlight focused on Ohio’s chief election official, Secretary of State Ken Blackwell. Like Harris, Blackwell served as a cochair of the Bush-Cheney campaign. He too was accused of making decisions – like refusing to count provisional ballots cast in the wrong precinct and infamously requiring that registration forms be on at least 80-pound paper weight – designed to benefit his party’s candidate in a key swing state.2 By 2008, a Democratic Secretary of State, Jennifer Brunner, had replaced Blackwell in Ohio, but this did not eliminate concerns about partisanship. To the contrary, 1 This paper uses the term “election administration” to refer to the set of nuts-and-bolts issues surrounding the mechanics and management of elections, such as voting technology, registration practices, provisional voting, voter identification, polling place operations, recounts and contests. I omit from discussion question of partisanship and nonpartisanship in other areas of election law, such as redistricting and campaign finance regulation. 2 For more on this and other controversies that emerged in the 2004 election, see Daniel P. Tokaji, Early Returns on Election Reform: Discretion, Disenfranchisement, and the Help America Vote Act, 73 GEO. WASH. L. REV. 1206 (2005). 3 Please don’t cite without permission Draft - 5/4/09 Republicans accused Secretary Brunner of being a sort of Bizarro-Blackwell, making decisions designed to benefit Democrats at the expense of Republicans.3 Accusations of partisanship by state and local election officials have triggered proposals to move to some form of nonpartisan or bipartisan election administration. Such recommendations have appeared in the reports of blue-ribbon commissions4 as well as in academic commentary by legal scholars5 and others.6 There have also been some efforts to reform state law to implement some form of nonpartisan election administration. A group called Reform Ohio Now put an initiative on the ballot in 2005 that would have transferred election administration authority from the partisan Secretary of State to an appointed bipartisan board 3 See Alan Johnson, GOP Crying Foul Over Absentee-Voting Law It Passed, COLUMBUS DISPATCH, Aug. 14, 2008 (quoting Deputy Chair of Ohio Republican Party as accusing Brunner of having a “troubling partisan agenda”). 4 See, e.g., COMMITTEE ON FEDERAL ELECTION REFORM, BUILDING CONFIDENCE IN U.S. ELECTIONS 50 (2005). 5 See STEVEN H. HUEFNER, DANIEL P. TOKAJI, & EDWARD B. FOLEY, FROM REGISTRATION TO RECOUNTS: THE ELECTION ECOSYSTEMS OF FIVE MIDWESTERN STATES 188-89, 196-97 (2007); Richard L. Hasen, Beyond the Margin of Litigation: Reforming Election Administration to Avoid Electoral Meltdown, 62 WASH. & LEE. L. REV. 937, 973-92 (2005). 6 See Robert A. Pastor, Improving the U.S. Electoral System: Lessons from Canada and Mexico, 3 ELECTION L.J. 584 (2004). 4 Please don’t cite without permission Draft - 5/4/09 5 Please don’t cite without permission Draft - 5/4/09 failed in 2005. That proposal was handily defeated.7 In Wisconsin, however, good government advocates succeeded in instituting a Government Accountability Board in 2007, whose members are selected through a process designed to ensure bipartisan support.8 There is some empirical research regarding the effects of partisanship on the decisions make by election officials which, by implication, sheds some light on what might be considered “best practices” when it comes to the institutions that run our elections. But there is not a lot9 – in my judgment, not enough to be confident in precisely what institutional reforms will work best at the state and local level. We may know (or think we know) that partisan election administration is a problem, but it is harder to know with any certainty what should be done about it. In the remainder of this paper, I summarize the research that exists and make some suggestions on what additional research, both empirical and legal, would be useful in developing reforms to election administration institutions at the state and local level.10 7 See State Issue 5: November 8, 2005, available at http://www.sos.state.oh.us/SOS/elections/electResultsMain/2005ElectionsResults/051108Issue5.aspx (accessed May 4, 2009). 8 See HUEFNER, ET. AL., supra note 5, at 115-17. 9 See David C. Kimball & Martha Kropf, The Street-Level Bureaucrats of Elections: Selection Methods for Local Election Officials, 23 REV. OF POL’Y RES. 1257 (2006)(“Despite the long-term existence of nonpartisan governing and its wide use among city councils, there is a dearth of empirical evidence to support policy changes, especially for local election officials.”)(citation omitted). 10 I omit, for purposes of this paper, reforms that might be made at the federal level to the 6 Please don’t cite without permission Draft - 5/4/09 Here’s what we know: At the state level, partisan election administration – at least in the sense that party-affiliated elected or appointed officials run elections – is the rule. According to Rick Hasen, 33 states have a chief election official who is elected through a partisan election process.11 Other states have an appointment process but, in many of those states, the chief election official is appointed by the state’s governor (who is of course elected through a partisan process).12 At the local level, about two-thirds of jurisdictions elect their election officials, and party-affiliated officials run elections in almost half of local jurisdictions.13 David Kimball and Martha Kropf have identified over 4500 local jurisdictions in the U.S.,14 and reported the following selection methods: Selection Method for Local Election Authority Selection Method Share of Jurisdictions Voter Representation Election Assistance Commission (“EAC”), the federal administrative agency with responsibility over election administration. For more on this subject, see Daniel P. Tokaji, Voter Registration and Institutional Reform: Lessons from a Historic Election, 3 HARV. L. & POL’Y REV. ONLINE (Jan. 22, 2009). 11 Hasen, supra note 5, at 974. 12 Id. at 974-75. 13 David C. Kimball, Martha Kropf & Lindsay Battles, Helping America Vote? Election Administration, Partisanship, and Provisional Voting in the 2004 Election, 5 ELECTION L.J. 447, 453 (2006). 14 Kimball & Kropf, supra note 9, Table 1. 7 Please don’t cite without permission Draft - 5/4/09 Individual Elected by Voters 61% 45% Elected Board of Elections 2% 1% Appointed Board of Elections 22% 31% Appointed Individual 15% 22% About 46% of local election jurisdictions had party-affiliated election authorities (20% Republican, 26% Democratic, and 0.1% other), while 14% had bipartisan and 29% nonpartisan local election authorities. Survey evidence suggests that this reality doesn’t square with the public’s views on who should be running elections. Michael Alvarez and Thad Hall report on a national survey that found strong support for nonpartisan boards. Of the general population, 66% thought that local or state election officials who run elections should be nonpartisan, while only 19.6% thought they should be partisan.15 Among registered voters, the percentage favoring nonpartisan election administration was even higher, at 72.6%. Only 1.5% of the general population and 0.9% of registered voters favored a partisan single elected official, the model that predominates at the state level, as opposed to a nonpartisan elected or appointed board. There’s also some evidence – though not a lot – that partisan election administration may affect the decisions election officials make. Here are the empirical studies that I’ve found on this 15 R. Michael Alvarez & Thad Hall, Public Attitudes About Election Governance (June 2005 manuscript), available at http://www.cppa.utah.edu/publications/elections/Election_Governance_Report.pdf. 8 Please don’t cite without permission Draft - 5/4/09 subject (and I’d be grateful for anyone letting me know of others that I may have missed): $ Guy Stuart examined the use of centralized voter lists to purge felons from Florida’s voting rolls. He found Florida counties with Republican election officials tended to be more aggressive in purging voters from the rolls than those with Democratic election officials. This is consistent with partisan motivation, since Democrats are generally believed to be more seriously harmed by overly aggressive purges.16 $ Kimball, Kropf & Battles found some evidence of an interaction between local election officials’ partisan affiliation and provisional voting practices. Democratic officials were slightly more likely to implement a more generous rule with respect to counting “wrong precinct” provisional ballots. In jurisdictions with a Democratic election authority, the number of provisional ballots counted as Democratic vote share increased. By contrast, in those with a Republican election authority, the number of provisional ballots decreased as the Democratic vote share increased.17 $ Anna Bassi, Rebecca Morton, and Jessica Trounstine examined the relationship between the party of local registrars and turnout in state elections. They found a strong positive correlation between the party of the registrar and the turnout of members of that party in gubernatorial elections. Bipartisan boards, on the other hand, tended to mitigate this effect.18 16 Guy Stewart, Databases, Felons, and Voting: Bias and partisanhip of the Florida Felon List in the 2000 Elections, 119 POL. SCI. Q. 453 (2004). 17 Kimball, Kropf & Battles, supra note 13, at 457-58, 459. 18 Anna Bassi, Rebecca Morton & Jessica Trounstine, Reaping Political Benefits: Local 9 Please don’t cite without permission Draft - 5/4/09 $ Joshua Dyck and Nicholas Seabrook examined the moving of voters to inactive status to Oregon which, in its “vote by mail” system, results in the voter effectively being disenfranchised. They found that Republican local election officials were more likely to move Democratic registrants to inactive status than Democratic officials.19 Collectively, these studies provide some evidence to support the claim that partisan election officials sometimes act to benefit their parties, rather than discharging their responsibilities evenhandedly. In conjunction with the anecdotal evidence described at the start of this paper, the empirical research helps make the case for moving toward some form of nonpartisan or bipartisan election administration. Reformers might also point to evidence of public skepticism regarding the honesty and fairness of elections. From 1996 to 2000, National Elections Studies data showed a sharp increase in the percentage of the public believing the election was “somewhat unfair” or “very unfair.”20 And a 37-country survey of conducted in 2004 found that the United States came in next to last (just ahead of Vladimir Putin’s Russia) in the percentage of citizens who rated the last national election “very honest” or “somewhat honest,” while a higher percentage of American citizens rated their last national election “very dishonest” than those in any of the other Implementation of State and Federal Election Law (July 22, 2008 manuscript). 19 Joshua J. Dyck & Nicholas R. Seabrook, The Problem with Vote-by-Mail, Paper prepared for presentation at the Annual Meeting of the Midwest Political Science Association (Mar. 18, 2009 manuscript). 20 Hasen, supra note 5, at 943. 10 Please don’t cite without permission Draft - 5/4/09 surveyed countries.21 Of course, at the time of this survey, the last presidential election had taken place in 2000. Still, this evidence bespeaks a lack of confidence on the part of many citizens in the integrity of election administration. That said, I think there’s a need for more research on the impact of partisan election administration. While there’s public concern about the honesty and fairness of American election administration, it’s not entirely clear that moving to nonpartisan election administration will actually improve public confidence. And while it may seem obvious to some that partisan election officials are more likely to make decisions that benefit their parties, there’s a need for more empirical research to augment that cited above and to verify that this is in fact the case. Furthermore, even if it were conclusively established that partisan election administration diminished public confidence and led to partisan decisionmaking, there would still be the question of what to do about it. Hasen has suggested that state chief election officials be nominated by the governor and approved by a supermajority of the state legislature (something like 75%), to ensure a consensus candidate who is above the political fray.22 Wisconsin has actually implemented an institutional reform designed to ensure evenhanded election administration, in the form of a Government Accountability Board whose members must be approved by a two-thirds supermajority of the state senate.23 Chris Elmendorf proposes a 21 Caroline Tolbert, Todd Donovan & Bruce E. Cain, The Promise of Election Reform, in DEMOCRACY IN THE STATES: EXPERIMENTS IN ELECTION REFORM 1, 7 (2008). 22 Hasen, supra note 5, at 984. 23 HUEFNER, FOLEY & TOKAJI, supra note 5, at 132. 11 Please don’t cite without permission Draft - 5/4/09 different institutional fix, in the form of advisory commissions like those used in the U.K.24 All these are promising ideas. But how well will they work? We really don’t know yet. This leads me to suggest three general areas in which more research would be useful. The first is more research on how partisan and nonpartisan election administration affects the decisions that are made. The studies identified in the bullet points above provide a helpful starting point, but more research along these lines would be valuable in confirming the intuition of many observers that partisan election officials make partisan decisions. The second area in need of further research is how partisan and nonpartisan election administration affects public confidence. There is survey evidence that Americans lack confidence in their system of election administration and think nonpartisan election administration is a good idea, but it would be helpful to “connect the dots” by demonstrating that people in jurisdictions with nonpartisan (or at least less partisan) election administration have greater confidence in their systems. Third, we need more research on what sorts of institutional arrangements work best. This might take the form of qualitative, comparative assessments of how different ways of running elections at the state and local level actually work in practice, of the type that my Moritz colleagues tried to do in From Registration to Recounts.25 In the meantime, one might fairly ask, what if anything should policymakers do? Should we try to muddle through with existing institutional arrangements, until we get a better sense of what their problems are and what should be done about them? On this point, I confess to being a 24 Christopher S. Elmendorf, Representation Reinforcement Through Advisory Commissions: The Case of Election Law, 80 NYU L. REV. 1366, 1395-1404 (2005). 25 HUEFNER, TOKAJI & FOLEY, supra note 5. 12 Please don’t cite without permission Draft - 5/4/09 bit conflicted. My ordinary instinct is to be cautious, in keeping with what I’ve termed the “Moneyball” approach to election reform which resists seat-of-the-pants judgments about what reforms should be implemented – something we’ve seen far too much of in recent years – and instead favors studious assessments of the evidence before changing election laws.26 At the same time, the lack of evidence on what institutional arrangements work best is partly due to the lack of experimentation, particularly at the state level. Although there are a variety of institutional structures at the local level, the vast majority of states still have either an elected or appointed partisan official running elections. It’s difficult to know what sort of institutional structure will work best when there has been so little variation and, therefore, comparative analysis of different alternatives. In sum, there’s a bit of a chicken-egg problem here. We don’t know what institutional arrangements will produce the best election administration to the shortage of research on the subject. But part of the reason for this paucity of research is that most states have the same type of state-level structure. For this reason, I’m inclined to believe that states should experiment with different institutional arrangements, as Wisconsin has done and as Reform Ohio Now tried to do, even without clear evidence on what the “best practices” are. Only through such experimentation, and through empirical and legal researchers carefully studying their results, will we ultimately develop election administration institutions that will better serve the needs of all citizens. 26 Daniel Tokaji, The Moneyball Approach to Election Reform (Oct. 18, 2005), available at http://moritzlaw.osu.edu/electionlaw/comments/2005/051018.php. 13