America's History Chapter 17 Capital and Labor in the Age of

advertisement

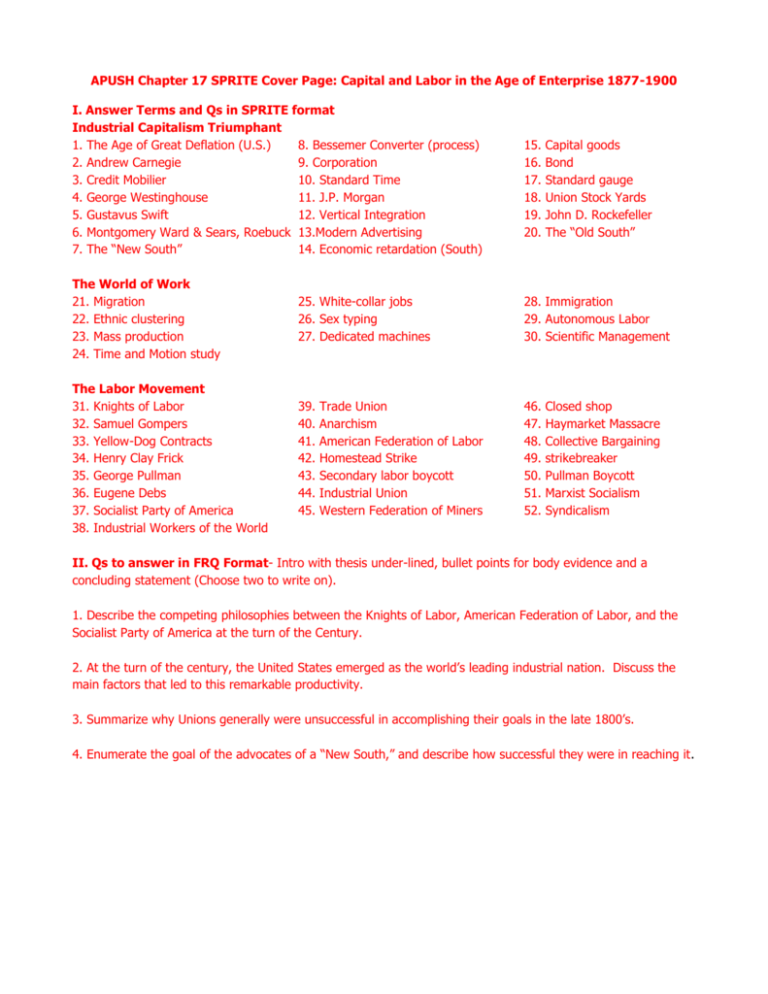

APUSH Chapter 17 SPRITE Cover Page: Capital and Labor in the Age of Enterprise 1877-1900 I. Answer Terms and Qs in SPRITE format Industrial Capitalism Triumphant 1. The Age of Great Deflation (U.S.) 8. Bessemer Converter (process) 2. Andrew Carnegie 9. Corporation 3. Credit Mobilier 10. Standard Time 4. George Westinghouse 11. J.P. Morgan 5. Gustavus Swift 12. Vertical Integration 6. Montgomery Ward & Sears, Roebuck 13.Modern Advertising 7. The “New South” 14. Economic retardation (South) 15. 16. 17. 18. 19. 20. Capital goods Bond Standard gauge Union Stock Yards John D. Rockefeller The “Old South” The World of Work 21. Migration 22. Ethnic clustering 23. Mass production 24. Time and Motion study 25. White-collar jobs 26. Sex typing 27. Dedicated machines 28. Immigration 29. Autonomous Labor 30. Scientific Management The Labor Movement 31. Knights of Labor 32. Samuel Gompers 33. Yellow-Dog Contracts 34. Henry Clay Frick 35. George Pullman 36. Eugene Debs 37. Socialist Party of America 38. Industrial Workers of the World 39. 40. 41. 42. 43. 44. 45. 46. 47. 48. 49. 50. 51. 52. Trade Union Anarchism American Federation of Labor Homestead Strike Secondary labor boycott Industrial Union Western Federation of Miners Closed shop Haymarket Massacre Collective Bargaining strikebreaker Pullman Boycott Marxist Socialism Syndicalism II. Qs to answer in FRQ Format- Intro with thesis under-lined, bullet points for body evidence and a concluding statement (Choose two to write on). 1. Describe the competing philosophies between the Knights of Labor, American Federation of Labor, and the Socialist Party of America at the turn of the Century. 2. At the turn of the century, the United States emerged as the world’s leading industrial nation. Discuss the main factors that led to this remarkable productivity. 3. Summarize why Unions generally were unsuccessful in accomplishing their goals in the late 1800’s. 4. Enumerate the goal of the advocates of a “New South,” and describe how successful they were in reaching it. America’s History Chapter 17 Capital and Labor in the Age of Enterprise I. Industrial Capitalism Triumphant (The Expansion of Industry) A. Growth of the Industrial Base 1. Early factories produced consumer goods-goods that replaced articles made at home or by individual artisans. 2. Gradually capital goods- goods that added to the productive capacity of the economy (goods used to make other goods)-began to drive America’s industrial economy. 3. Bessemer Process: In 1856, British inventor Henry Bessemer designed the Bessemer converter, a furnace that refined raw pig iron into steel, which is harder and more durable than wrought iron. In 1872, Andrew Carnegie erected a massive steel mill that used the Bessemer converter; the Edgar Thompson Works of Pittsburgh became a model for modern steel industry. The technological breakthrough in steel spurred the intensive mining of some of the country’s rich mineral resources; Iron ore and coal. 4. The nation’s energy revolution was completed with the coupling of the steam turbine with the electric generator, after 1900, American factories began a conversion to electric power. B. The Railroad Boom 1. Americans were impatient for year round on time transportation service that canal barges and riverboats could not provide. The arrival of locomotives from Britain in the 1830’s was the solution. 2. The U.S. chose to pay for its railroads by free enterprise, but the governments of many states and localities lured railroads with offers of financial aid. The corporation (allowed companies to raise large sums of money): was a legal form of organization that provided investors limited liability. Railroad promoters ran the railroad construction companies, which raised cash by buying and selling railroads’ bonds. 3. A problem of early railroad companies was the gauges of track varied widely, and terminal points were not connected. By the end of the 1880’s standard gauge had been established (4’- 81/2”). This allowed locomotives to travel anywhere track was laid. 4. Railroad Time: In order for the Railroad to operate efficiently they had to come up with a way to keep time over long distances. In 1870 Professor C.F Dowd proposed that the earth’s surface be divided up into 24 times zones (one for each hour of the day) The U.S was divided into four different zones: Eastern, Central, Mountain, and Pacific. Railroad time was adopted by Congress in November of 1883. 5. The inventor George Westinghouse perfected the automatic coupler, the air brake, and the friction gear. These all resulted in a steady drop freight rates for shippers. * Early on there were many RR companies and the competition was fierce. 6. For investors, the price of railroad competition was high; when the economy turned bad, as in 1893, a third of the industry went into debt. After 1893, the investment banks of J.P Morgan & Co. and Kuhn Loeb & Co., stepped in to court new investors and consolidate old railroad rivals. This reorganization shifted the nerve center of American railroading to Wall Street. By the early twentieth century, a half dozen great regional systems had emerged out of the jumble of rival systems. C. Mass Markets and Large-Scale Enterprises 1. Until well into the Industrial age, most manufacturers operated on a small scale for nearby markets and left distribution to wholesale merchants and commission agents. 2. As America’s swelling population flocked to the cities (immigration and migration), the railroads brought tightly packed markets within reach of far off producers (connected distant markets together). The Union Stock Yard of Chicago opened in 1865; livestock came in by rail from the Great Plain, was auctioned off in Chicago, and then shipped east for processing in “butcher towns.” 3. Vertical Integration-Controlling all phases of production: Gustavas F. Swift and his engineers developed an effective cooling system for shipping beef. Swift invested in a fleet of refrigerator cars and built a central beef-processing plant in Chicago as well as a network of branch houses. Swift vertically integrated, absorbing the functions of many small, specialized enterprises within a single centralized structure. 4. Horizontal Consolidation; buying out your competition (once you have eliminated the competition in a region you can raise your prices). John D. Rockefeller’s Standard Oil Company eliminated competition by undercutting prices. 5. By the late nineteenth century, modern advertising appeared as big businesses set about creating a national demand for their brand names. D. The New South 1. After the Civil War, the South remained overwhelmingly agricultural, and wages for farm labor in the South were low. 2. Southern textile mills recruited workers from the surrounding hill farms; mill wages exceeded farm earnings, but not by much. The new southern mills had an advantage over those of the long-established New England industrysouthern mills’ wages were as much as 40% less. A “family system” of mill labor developed, with a labor force that was half female and very young. Blacks sometimes worked as day laborers and janitors but seldom got jobs as operatives in the cotton mills. 3. The businesses that developed in the South produced raw materials or engaged in the low tech processing of coarse products. The South consistently lagged behind the North economically. Many southerners blamed the North for economic disparity; as most of the capital came from the North. 4. Low wages in the South discouraged employers from replacing workers with machinery: Attracted labor-intensive industry and inhibited investment in education. 5. Northerners and immigrants avoided the South and its low wages. Surprisingly few southerners left for the higher wages in the North (after WWI the Great Migration will begin). II. The World of Work A. Labor Recruits 1. Unlike Europe, the U.S did not rely primarily on its own population for a labor supply: 2. The U.S. demand for labor tripled between 1870 and 1900; Filled with migration and immigration: White collar jobs were filled by White Americans. Industrial work (blue collar) was filled by immigrants (willing to work for cheap wages). Casual labor, janitorial, and domestic work went to African Americans. 3. Ethnic origin largely determined the kind of work immigrants took in America: The Welsh were mostly tin-plate workers English were miners Germans were machinists, etc 4. With the advance of technology, fewer European craftsmen were needed, yet the demand for ordinary labor skyrocketed. 5. By 1895, arrivals from southern and Eastern Europe far outstripped immigrants from Western Europe Heavy, low paid labor became the domain of the immigrants; their relatives and neighbors often followed them to America, and a high degree of clustering resulted (ethnic neighborhoods). Immigrants were often peasants displaced by the breakdown of the traditional rural economies of southern and Eastern Europe; many returned home during America’s depression years. 6. In 1900, women made up a quarter of the nonagricultural labor force. Contemporary beliefs about woman hood determined which jobs women took and how they were treated at work. Women were not permitted to do “men’s work” nor were they paid the same wages as men, regardless of their skills. Employers maintained that because women had men to support them, they did not require a “living wage.” By 1890: Fewer than 5% of white wives had worked outside the home (married women not expected to work) and more than 30% of black wives worked for wages (economic survival). 7. At the turn of the century women’s work fell into three categories: Domestic service, female white collar jobs, and industry such as the garment trade. 8. The family household could not function without the wife’s contribution; therefore, society disapproved of wives taking paying jobs. Working-class families had a hard time getting by on one income; in 1900, one in five children under the age of sixteen worked. By the 1890’s, all of northern industrial states had passed child labor laws and regulation on work hours for teenagers. 9. Deprived of their children’s earnings, yet still needing more than one income, more women in working-class families entered the workplace. B. Autonomous Labor 1. Autonomous (unsupervised) male craftsmen flourished in many branches of nineteenth-century industry. For men, dispersal of authority was characteristic of nineteenth century industry; the most skilled workers were autonomous-hiring, supervising, and paying their own helpers These workers abided by the “stint”, an informal system of restricting output that infuriated efficiencyminded engineers. 2. Many female workers found a new sense of independence and new social outlets form working. 3. Women workers rarely wielded the kind of craft power that the skilled male worker commonly enjoyed C. Systems of Control 1. With mass production, machine tools became more specialized, and the need for skilled operatives disappeared. Employers were attracted to “dedicated” machinery because it increased output; the impact on workers was not their greatest concern (profit was). 2. Frederick Winslow Taylor’s method of scientific management eliminated the brainwork from manual labor and deprived workers of the authority they had previously known. Influenced by Taylor, managers subjected tasks to time and motion studies in order to determine the workers’ pay (Taylor assumed that workers would automatically respond to the lure of higher earnings. 3. Scientific management did not solve the labor problem as Taylor had thought it would, rather it embittered relationships on the shop floor. 4. For textile workers, the loss of autonomy came early; for miners and ironworkers, it came more slowly; and construction workers mostly retained their autonomy. III. Labor Movement A. Reformers and Unionists 1. The Knights of Labor was founded in 1869 as a secret society of garment workers in Philadelphia and by 1878 had emerged as a national movement. To achieve labor “emancipation,” the Knights had originally intended to set up factories run by the employees; led by Terence V. Powderly (egalitarianism between employers and workers). They instead devoted themselves to “education” (teach their theory). 2. The labor reformers expressed the higher aspirations of American workers, but the trade unions tended to the workers’ day to day needs. Better wages, shorter hours, safety in the workplace, etc. 3. The earliest unions were organizations of workers in the same craft and sometimes the same ethnic group. By the 1870’s the national union was becoming the dominant organizational form for American trade unionism. Many workers carried membership cards in both the Knights of Labor and a Trade Union. 4. The Knights of Labor and most trade unions barred women until 1881, when women shoe workers won the right to form their own local assembly. The Knights of Labor allowed black workers to join out of the need for solidarity and in deference to the Order’s egalitarian principles. B. The Triumph of “Pure and Simple” Unionism 1. In the early 1880’s the Knights began to act more like trade unions; as they won more strikes, its membership rapidly increased. 2. Samuel Gompers led an ideological assault on the Knights (fearing they were becoming too powerful), and hammered out the philosophical position known as pure and simple unionism Knights should concentrate on Reform Trade Unions will worry about workers needs. 3. Employers fight unionism: Seizing on the anti-union hysteria set off by the Haymarket affair, employers broke strikes violently, compiled blacklists, and forced some workers to sign “yellow-dog-contracts” that renounced union membership. 4. In December of 1886, the national trade unions formed the American Federation of Labor (AFL); the underlying principle was that workers had to take the world as it was. The Knights of Labor never recovered from the Haymarket affair, and by the mid-1890, the Knights had faded away while the AFL took firm root. C. Industrial War 1. American trade unions wanted a larger share for working people; this made employers opposed to collective bargaining. 2. Carnegie decided that collective bargaining had become too expensive and wanted to replace the workers at his steel mill in Homestead, Pennsylvania, with advanced machinery. Carnegie’s second in command, Henry Clay Frick, announced that Carnegie’s mill would no longer deal with the Amalgamated Association of Iron and Steel Workers. The Homestead strike of July 6, 1892, ushered in a decade of strife that pitted working people against the power of corporate industry often by the gov’t. 3. George Pullman, cut wages at his factory but not the rents for employee housing. Pullman workers belonged to the American Railway Union (ARU), and Eugene Debs directed all ARU members not to handle Pullman sleeping cars (secondary labor boycott). 4. The Pullman boycott was crushed by the federal gov’t, which pressured was pressured by the railroad companies used its power to protect the U.S. mail carried in railcars. 5. Bottom Line: Big Business is in charge in the late 1800’s: Support of the gov’t Yellow Dog Contracts Public’s perceptions that the Unions were responsible for the violence during strikes. D. American Radicalism in the Making 1. Eugene Debs devoted himself to the American Railway Union, a union that organized all railroad workers irrespective of skill (an industrial union). 2. With the formation of the Socialist Labor Party in 1877, Marxist Socialism established itself as a permanent presence in American politics. After being incarcerated after the Pullman strike, Debs gravitated to the socialist camp and helped to launch the Socialist Party of America in 1901. 3. Under Debs, the Socialist Party of America began to attract not only immigrants but farmers and women as well. 4. The Western Federation of Miners joined left-wing socialists in 1905 to create the Industrial Workers of the World (Wobblies). The Wobblies supported the Marxist class struggle at the workplace rather than in politics.