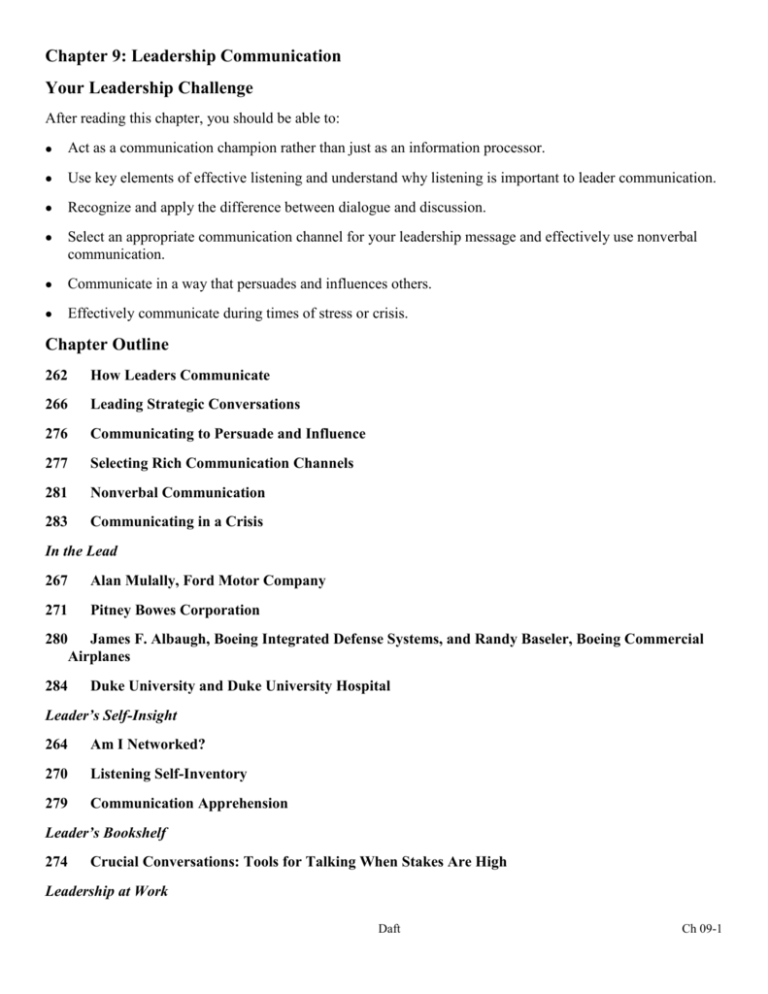

Chapter 9: Leadership Communication

advertisement