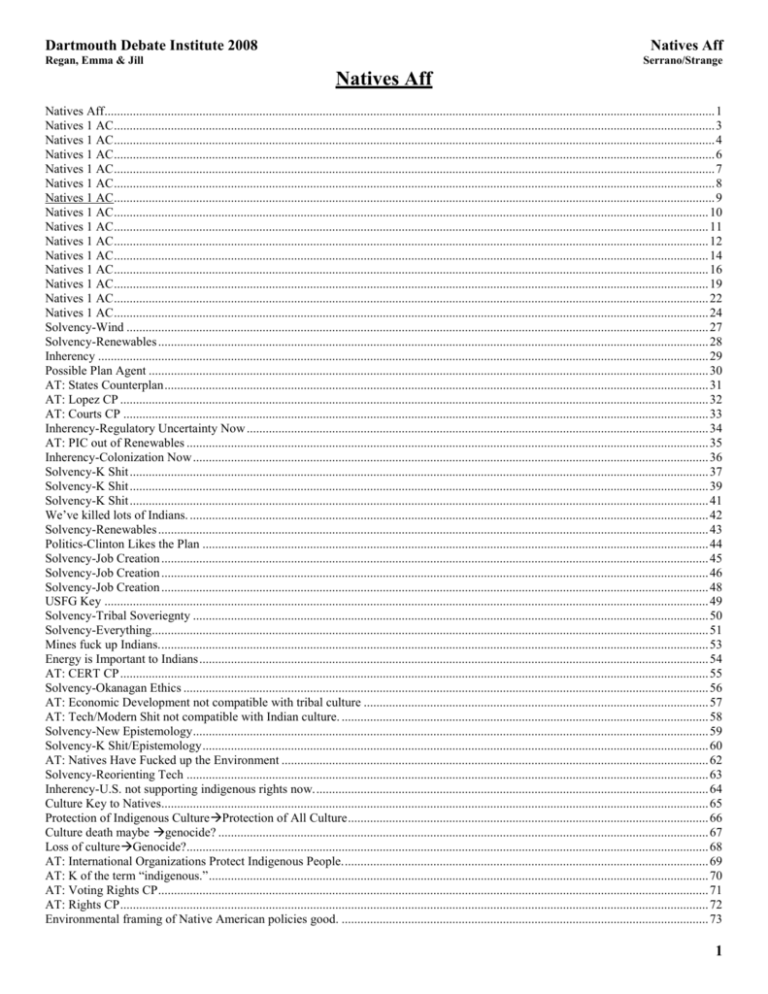

neg—efficiency solvency—econ

advertisement