The Author/Date citation system – a short summary Adapted from

advertisement

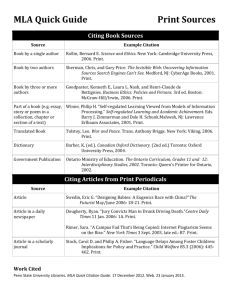

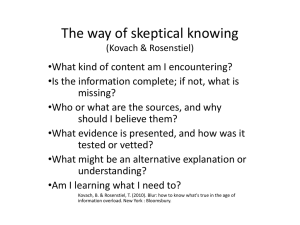

The Author/Date citation system – a short summary Adapted from The Chicago Manual of Style (University of Chicago Press 2003, 616624) by David Clowney August, 2012 When you write academic papers, you are required to say where you got any words or ideas that are not your very own original contributions, unless they are common knowledge. Doing this is called citing your sources. Not doing it is called plagiarism. There are several accepted ways of citing sources. The standards of the Modern Language Association (MLA) and the American Psychological Association (APA) are just two examples. I will accept any of these standard systems. The system I use is called the Author/Date system. It is common in the sciences, and has recently become popular in many humanities disciplines as well. If you don’t already have a standard system that you’re used to, I recommend it to you. The author/date citation system has several advantages both for authors and readers. It is a lot more efficient than other systems. It doesn’t rely on little known Latin abbreviations that are hard to keep straight. It tells readers right away, in the body of the text, where a particular idea or quotation comes from, and saves footnotes and endnotes for additional content that doesn’t belong in the text itself. All citation systems have the same purpose. They locate your academic writing within the scholarly world on which it depends and with which it is in conversation. They help an interested reader know where to find what you are citing, so she can learn more, form her own ideas about the evidence, fact-check you, and in general do more than just take your word for things. They also keep you honest, by obliging you to credit the source for any words or ideas you use that are not either common knowledge or your very own original contribution. Finally, they force you as an author to be very careful about attributing words and ideas to someone else unless you can prove the person actually said those words and has those ideas. Proper citation trains you to be a much more accurate reporter and interpreter of other people’s work than you otherwise would be. Once you get used to using a citation system correctly, you will start noticing the differences between different systems. Settle on one academically standard system that you prefer, and use it consistently when you have the choice. But be prepared to adapt to different systems in different contexts. Different professors may require you to use different systems. And if you go on to publish in academic journals, or do any other sort of professional writing, you will find that different journals and publishers have different stylebooks. Check their “Instructions for Authors” page before you submit something for publication, and format your submission to match their requirements. Knowing one system will help you notice how theirs differs from yours. Here’s my version of the author/date system. General principles of the author/date system of citation: 1. Every citation has two parts. a. The reference list gives the full bibliographic details for each work cited: see below for what it should look like. It comes at the end of your paper, with a heading like “References” or “Sources Cited”. b. In the body of the paper, each time you cite a work, you should include a parenthetical pointer to the references page, consisting of the author’s last name, the date of the publication you’re pointing to, and in most cases the specific pages to which you are referring. Again, see below for what this looks like. A citation is not complete unless both parts are present. 2. In the author/date system, footnotes and endnotes are never used for citations. Use them only for material you want to include, but don’t want to put in the main body of the paper. 3. The author/date system of citation is the norm in the sciences and the social sciences, but is gaining popularity in the humanities (e.g., in philosophy). When used in the humanities, it often appears in a hybrid form. Thus, full names of authors usually appear in the reference list, whereas the sciences and social sciences often give only the last name and initials. When this system is used in the humanities, titles of books often appear in italics, and titles of articles in quotation marks, and both are capitalized in headline style, where science publications customarily don’t use quotation marks for any titles, use italics only for journal titles, and capitalize both book and article titles in sentence style. Finally, page numbers are more likely to be used in humanities citations than in science citations (partly because humanities publications are much longer, on average, than science papers, and the humanities pay more attention to the way things are said). Don’t obsess about these details; pick a variant that makes sense to you and use it consistently. The examples below are in the hybrid style that I use. Specific details of the author/date system: The first half of the system: In the reference list, use the following conventions: Book (three examples – a book with a single author, a translated and revised work, and a work authored by an institution with no individual author or editor listed): Shiner, Larry. 2001. The Invention of Art: a Cultural History. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. Plato, G.M.A. Grube trans., J. M. Cooper rev. 2002. Five Dialogues: Euthyphro, Apology, Crito, Meno, Phaedo, 2nd edition. Indianapolis, IN: Hackett Publishing. University of Chicago Press. 2003. The Chicago Manual of Style, 15th ed. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. Notice my use of “trans.” for “translator” and “rev.” for “reviser”. You could also spell these out; it’s your choice, just be consistent. Journal article: Geach, P.T. 1966. “Plato’s Euthyphro: an Analysis and Commentary.” Monist 50:36982. Citation from a web-page: Frede, Dorothea. 2009. “Plato’s Ethics: An Overview.” Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Summer 2009 edition), Edward N. Zalta ed. http://plato.stanford.edu/archives/sum2009/entries/plato-ethics/. Accessed August 30, 2012. Note: this source includes a guide for citing it, and as a peer-reviewed online academic source it is very careful about this. Many internet sources are not. But even this source does not have page numbers, so if you need to cite a particular passage in a long entry, use the entry’s section numbers as locators in place of page numbers. Citation of a personal conversation: You may have gotten your idea from a friend, or from an interview of some expert. You may simply mention this in your text, or you may cite it like this: (John Brody, personal communication, October 2012). You could include this in the references page or only in the body of the text. The Chicago manual tilts in the direction of handling such communications informally, but gives methods for citing them. The basic principle still applies: everything that is not your own original words and ideas, and is not common knowledge, needs to be attributed to the source from which you got it! Other cases: There are a great many of these, including television shows, radio broadcasts, CD’s, mp3 files, YouTube videos, tweets, political speeches, . . . the list goes on. Do your best! If you don’t know what to do, look it up in the Chicago Manual of Style. If you still don’t know what to do, ask! In most of my classes, I only care about the main principle, namely crediting all your sources, and tying them to the actual place in your paper where you are using them. Don’t obsess, do your best. The second half of the system: In the body of the text, use the following conventions: Citing a work as a whole: Larry Shiner argues that the term “art” as we now use it refers to a system of practices, institutions and concepts that was invented in the 18th century west (Shiner 2001). Citing a particular location in a work: follow the author and date with a comma and the page number(s). E.g., (Shiner 2001, 25-33). If there are no page numbers (as is the case for many web-pages), and the reader might have a hard time finding the passage you’re citing, mention whatever location markers may be present (e.g., section numbers, subheadings, even nearby images, or if all else fails, approximate locators like “about two-thirds of the way through the article”). Classic texts in translation often have standard location markers in the margins (these are usually tied to locations in standard critical editions of the original text). When you are citing such a text, you may substitute these location markers for the standard parenthetical mini-citation in the body of your text, like this (Euthyphro 6c). This is the only exception I know to the standard practice for the author date system. You should still include the full citation for the translation or edition you are using in your reference list, so that readers will know what translation or edition you are using. Footnotes and endnotes in the author/date system: In this system, as previously noted, you don’t use notes to cite sources. But you might cite a source in a note. If you do that, treat the citation the same way you would in the body of the text. Use an abbreviated parenthetical pointer (Author Date, pp.) and include the full bibliographic citation in the reference list.