Goals and rationalities in work related learning

The learning potential of the workplace 1

An overview of a research programme.

Loek F.M. Nieuwenhuis, (IVA, Tilburg University & Twente University NL), Wim J. Nijhof

(Twente University, NL) & Marianne Van Woerkom (Tilburg University, NL)

Contact: lni@stoas.nl

Abstract

The Dutch research program on the learning potential of the workplace started officially in 2001 and has ended 2008. Two PhD studies are finished (Blokhuis, 2006; Poortman 2007) adn two other projects are now in their final stage and will present their final results during 2009-2010. In this paper we present an overview of the rationale of the program, and we will present preliminary results of the research projects. An overview of the program results is published by

Nijhof and Nieuwenhuis (2008).

The lever for improving work based learning has to be found in combining the logic of work with educational professionalism (Saljö, 2003). A single educational, preparatory approach will not be successfully implemented in work organisations. Reflective interaction, collaboration and performance orientation as educational interventions have to be translated into work oriented interventions, in which productivity, efficiency and quality of work are leading issues. The optimisation of skilling trajectories for work and occupations have to be seen as an arena in which educational rationalities and work oriented rationalities have to be intertwined and negotiated.

Introduction

Recent insights claim the workplace being an environment with high learning potential. Main arguments are the possibility to combine formal and informal learning, the possibility to work and learn individually and collaboratively and the possibility to exchange experiences between novices and experts. Despite these claims, there is no clear empirical evidence that the workplace is a strong learning environment. Studies show that the workplace is not always effective as learning environment and that there are many misconceptions of learning at the workplace. This research program aims to challenge these claims on the learning potential of the workplace by combining systematically five complementary research projects.

The first project takes a curriculum approach, by modelling and testing different configurations of the workplace, based on recent insights and models.

The second project investigates the different returns of the two major pathways to becoming skilled in the Dutch VET-system: apprenticeships versus school based education.

The third project combines educational and micro-economic theories on reflective learning within communities of practice and innovative behaviour of companies. The work of Wenger (1998) and Nonaka & Takeuchi (1996) are main sources for this project.

1 Acknowledgements

This paper is developed within the research programme "the learning potential of the workplace". This programme is chaired by prof. W.J. Nijhof of Twente University; Twente University, Utrecht University and

Stoas Research in Wageningen carry out projects. The programme is granted by NWO, the Dutch foundation for scientific research.

A fourth project is added to the programme in 2004; this project is an evaluation of dual trajectories (combinations of school based and work based learning) in higher professional education.

The last project is a synthetic study, which will combine the results of the other three projects. This project has led to a corner stone publication on work based learning, based on discussions within two international expert meetings (Nijhof & Nieuwenhuis,

2008).

An important premise underlying organising work based learning is that it can provide more

"authentic" learning experiences for students than formal learning (Stasz & Kaganoff, 1997). So, the learning potential of the workplace is based on it's authenticity and not on it's orientation on learning. The opponents in the debate on work based learning stress the orientation on labour productivity of the workplace: learning is only a side-effect of work activities. Bolhuis and

Simons (1999) take a slightly different position in stating that working (as most human activities) is always connected to learning, but workers are not always aware of their learning activities and are not learning effectively from an organisational perspective. The different positions lead towards different types of hypotheses on the learning potential of the workplace:

1. School based learning and work based learning are useful for different purposes; school based learning is effective for instructional goals (transfer of codified information and knowledge) whereas work based learning is effective for constructivist goals (negotiation of meaning [cf. Wenger, 1998], and the acquisition of tacit knowledge, under condition of posthoc reflection and guidance);

2. Work based learning can be effective under specific organisational conditions: learning opportunities can be organised in more and less effective manners within the organisation of production. Work based learning is depending on production conditions;

2a Work based learning is depending on the openness of the work organisation: opportunities to boundary crossing (Engestrom) or travelling between communities (Wenger) are important for "neue Combinationen" (relation between core competence of companies and individual competence)

3. Work based learning can be effective under specific individual conditions: workers can be made aware of their learning activities, which can improve the impact of working on learning;

4. The meaning of "learning" for individuals is an important intermediate for the effectiveness of work based learning. "Learning" is often connected to (negative) school experiences (see

Simons, 2001), by which informal learning is not recognised as such;

For testing these different hypotheses and challenging the learning potential of the workplace, the five research projects each take specific perspectives and points of departure. The last, integrating project is aimed at combining and integrating the outcomes of the other four projects.

In the second half of the program period, preliminary results will be discussed with an expert panel for catching up with the international debate.

Goals and rationalities in work related learning

Before industrialisation, work and learning were organised organically within local economies.

However, with the rise of the industrial era, the need for a well-trained labour force caused work and learning to become more and more organised in strong societal systems, built on specialised organisations and institutional frames. We might say that the industrial revolution forced an educational revolution, at least in Western economies. Where, before industrialisation, learning and work coexisted in a non-formal way, both human activities became rationalised, formalised and separated into different systems, from the end of the nineteenth century. The rationalisation of work and the princip les of ‘scientific management’ (Taylor, 1911) enhance a serial relation between training and work, in which training and learning are preparatory to work.

Work is intentionally designed with a minimum of learning opportunities for workers, since learning means running the risk of a loss of routine, stability and efficiency, and might therefore lead to lower productivity and higher costs. The separation of planning and performing, and dividing work into simple tasks is paramount.

The emergence of a knowledge-based economy has been predicted since 1970 (cf.

Lindley, 2003). The rapid rate of innovation, combined with a high level of obsolescence of knowledge and skills, should stimulate efforts to redesign the relation between training and work. Work can no lon ger be organised based on Taylor’s rationalised models, but should be organised within learning organisations and self-steering work teams. Innovation will become an intrinsic part of work: work and learning will coexist again, not only for apprenticeship programmes as in the times of the guilds, but as a common characteristic of expert work at all levels. Brown and Keep (1999) criticise this euphoric welcoming of a new economic era, by stating that Fordism is still a growing and powerful model, at least within the UK economy.

Mayer (2002) argues that companies, also in a knowledge-based economy, are able to keep up competitiveness based on a technical organisation of innovation, in which the division of labour has become even deeper. Thus, the emergence of a knowledge-based economy gives a diffuse picture, with large differences between national economies, sectoral patterns and differences between companies. However, flexibility and change will increasingly become part of the routine organisation of work (cf. Nijhof e.a., 2002), resulting in a greater emphasis on learning while working.

The serial model for learning and work, in which learning only has a function in preparing for work, will have to be combined with new rationales for work and learning. As long as work targets are fixed, targets for work-related learning could be derived with some regularity.

However, for the economic survival of work organisations, vitality through innovation is essential. Innovation is a 'target-less' process, especially in the creative phase (Nooteboom,

2000), because of its aim of creating something new. Innovative processes go hand in hand with learning processes (Hoeve, Mittendorff & Nieuwenhuis, 2003), both at the individual and collective level.

Not only will the relation between work and learning have to be redesigned in the transition towards a knowledge-based economy: the relation between work and human life is also changing. "Working for a living", as the relationship between work and life could be characterised in the industrial era, should now be replaced by "working as a way of life", stressing the penetration of work into the whole life of workers. We therefore have to reckon with different rationalities when describing the relation of learning and working. We distinguish four types of rationalities (for an extensive elaboration, see Nieuwenhuis & van Woerkom, 2007;

Nieuwenhuis, 2004):

a preparatory rationality, in which learning is seen as preparation for work;

an optimising rationality, in which learning is seen as part of the execution of work;

a transformative rationality, in which learning is seen as a way of innovating work;

a personal rationality, in which learning is seen as part of the balancing process between work and other elements of public and private life.

The phenomenon of work based learning and the learning potential of the workplace should not be discussed only from the preparatory, educational perspective. To understand learning processes at work, the other rationalities are important to keep in mind, also when discussing work based learning in the course of initial training trajectories. The outcomes of apprenticeships and internships can only be understood when taken into account that students on the workplace take over the “local” rationality of production and innovation: their personal goals are often to become as soon as possible an acknowledged member of the community of work.

Economy of learning within communities of practice

In the project of Hoeve, the target of investigation is relation between work based learning and enterprise innovative strategies. Innovative organisations are emergent structures and continuously trying to adapt to a changing environment. Influenced by industrial scientists who discovered the human factor an important source of economic growth, work-related learning is seen as an integral part of the current post-Taylorist work organisations (Senge, 1990; Nonaka and Takeuchi, 1995; Argyris and Schön, 1996; Garrick, 1998; Ellström, 2001). Innovation, or better the innovation process, can be treated as the equivalent of an organisational learning process. Logically, it is argued that to understand innovation we need to develop an (interactive) learning theory (Nonake & Takeuchi, 1995; Nooteboom, 2000).

Jorna and Van Heusden (2000) criticise the learning organisation concept by pointing out organisations cannot learn; only individual members of an organisation are able to learn.

Nooteboom (1996) notes that an obvious point is that learning appears to be an attribute of people, not firms, so that learning by the firm must be reconstructed from learning by people.

Work related learning could be seen as the key to understand the current transition from a postindustrial society towards an information (or knowledge) society at both individual and organisational level, as work-related learning is the central characteristic of both the modern

`knowledge’ worker and the innovative work organisation. The question is how work-related learning is interconnected at these different lev els? As Marsick and Watkins (2001) put it: “what happens in the intersection between individual and team, or team and organisation?” By studying learning in innovation processes we hope to develop a clear understanding of this intersection in order to bridge individual and organisational learning (cf Hoeve e.a., 2003).

We define the process of changing routines as collective learning (cf. Ellström, 2001: 422, who defines organisational learning as a change in organisational practices, including routines and procedures, structures, technologies, systems, and so on). Collective learning logically implies individual learning, but not vice versa. Individual learning results in a changed script. Individual learning is only the first phase of innovation, which should be followed by the establishment of new routines. The crux in linking this kind of learning to innovation is that this individual action has to be followed by collective action. As routines are recurrent collective activity patterns, routines can be broken up by one individual but not newly established by any individual. Thus individual learning is a necessary but not sufficient condition for collective learning to occur.

Individual learning leads through the internal psychological processes of acquisition, to the development of cognitive structures of knowledge. Scripts can be seen as cognitive structures of procedural knowledge (knowing how to act). An individual uses the script to, almost unconsciously, undertake appropriate actions in the situations he is confronted with at work.

However, the (changed) script is only a sub result of the learning process Illeris (2002) emphasises that at the same time also psychodynamic patterns of emotions, motivations and attitudes are developed in an integrated way. We thus need to be aware that change of scripts goes together with the change of psychodynamic patterns.

Illeris (2002) states that these interaction processes can be characterised as perception, transmission, experience, imitation, activity and participation. As we are interested in how an individual learning process leads to a collective learning process, we are particularly interested in the characteristic of participation. It is through participation that individuals tune their own learning process to the learning process of others, which might lead to a collective learning process. Moreover, through participation individuals also might actively influence the direction of the learning process of others.

Influencing others is necessary; as a routine is a collective recurrent pattern, the establishment of a new routine can only be done by the collective. An innovative Community of Practice thus

has to organise a collective learning process, whereby the group take over the changes proposed by this critical reflective individuals. This collective learning process seems more adaptive learning. This makes clear that the main models of learning, developmental and adaptive learning, are not mutually exclusive but complementary. The complex character of an innovation process requiring both creation and performance indicates that both forms of learning need to be used. The crux for an innovative Community of Practice is the co-ordination between adaptive and developmental learning at both individual and collective level.

Experiences gained through a case study in an industrial bakery show that social aspects are quite important in this collective learning process: status and positions change during such drastic turn-around processes (cf. Hoeve & Nieuwenhuis, in press). What is at stake in innovation is the routines and the attached roles of the employees. Both are bound to the specific setting of a bakery: although the process is automated to a large extent, employees see themselves still as bakery experts. Loosing their craft is felt as loosing their pride (cf. Wengers concept of negotiation of meaning).

A former change (in 1985) from artisanal to industrial production was so radical because not only the nature of the work routines changed but with that also the roles changed. The position of individuals in the bakery was no longer related to craftsmanship. Craft bakers lost their craft status and had to regain a position based on their ability to work with the technology.

The recent introduction (2003) of a robotized line within the industrial production is seen as a challenge: operators are eager to conquer and to develop the new required routines. It is a reciprocal process between men and machine; both sides need to be adjusted to one another.

The eagerness is surprising, in the light of the supposed conservatism in communities of practice. One explanation can be that, although the technical innovation of the new line is quite large, the impact on existing routines and scripts is relatively low: the new line is not impeding on the distribution of expertise and the cultural meaning inside the teams. The new line can be seen as a tool to raise the professional standard on the shop floor. Another explanation can be the smooth preparation of the implementation stage by involving shop floor employees is the experimental stage. By involving a key person from the shop floor a knowledge broker (cf

Engeström, 1999) has developed within the community of practice. In this case the foreman is essential, but not always formal position and informal status coincide

The introduction of the new line in 2003 has not been experienced as dramatic as the introduction of automation in 1985. The 1985 change was not only a technical revolution but also a cultural shock: the 2003 change is seen as an improvement of technicalities.

In this case study we have explored possible key concepts that helps explaining what happens at the intersection between individual and team, and team and organisation. We conclude that the concept of routines is the most sufficient for such understanding. Routines are collective recurrent activity patterns: they describe what is done by whom and why. Routines are schemes for both understanding and behaviour: to understand something is to be able to correctly perform a practice. Routines provide the framework for individual recurrent patterns and thus link the collective and the individual. Simultaneously, routines link the collective to the larger organisation, as organisations are a set of interlocking routines. Routines, thus, serve as the coordinating mechanism between the different aggregation levels.

We might interpret routines as a set of `default rules’: they apply until challenged, and then if in context the challenge works, the routine is changed. Innovation can be understood as the change of routines. To understand how routines are changes, we modelled this process as a combined individual and collective learning process. As learning is an integrated process of acquisition and interaction processes, not only cognitive but also social and emotional aspects are very important. In the next stage of this research the impact of social factors and emotional factors on the process of routine change will be researched.

Towards a model for vocational skill formation

The project of Poortman (2007; cf. Poortman, Nijhof & Nieuwenhuis, 2004) is targeted at investigating the role of different trajectories to becoming skilled. In the European discussion on vocational education and training apprentice schemes and school based schemes are the main appearances of skilling trajectories. Within Dutch VET, both schemes are operating synchronously. In her project, Poortman investigates the impact of these schemes.

Onstenk (1997) presents a model for traineeship learning. Performing learning activities, distinguished in processing, performing and meta-cognitive -activities is central in his model; they are influenced by internal and external processes. Cseh, Watkins and Marsick (in: Marsick

& Volpe, 1999) provide a model for informal and incidental learning in which the (informal) process is described in more detail. Interpreting experiences, examining alternative solutions, choosing learning strategies, producing the proposed solutions, accessing intended and unintended consequences, planning next steps, while framing the business context are steps of this (circular) model. Eraut (2000) referring to Horvath et al (1996) goes into the memory structures involved in implicit learning and tacit knowledge. He explains the processes of tacit learning as a path that directly influences behaviour from the episodic memory (not mediated by the generalised knowledge representations in semantic memory). The knowledge derived from this path, through tacit learning, is ready to use in contradiction to the public propositional knowledge that is too abstract to be used without considerable further learning (Eraut, 2000, p.118). This means that tacit knowledge is central to everyday action.

An aspect that needs further elaboration is the level at which learning processes will be explored in the present study. In the literature, sometimes the activities that lead to learning are presented as elements of the process, for instance 'practising', or only the resources are identified: 'learning from manuals', 'learning from videos'; examples of the broader processes such as 'peripheral participation' frame a set of activities (in this case observation, listening, facilitation through job-rotation and alertness and receptivity of the learner; self-directed learning and structured personal support for learning) (Eraut, Alderton, Cole and Senker, 1998).

Illeris (2002, p.24) broadly perceives learning to be 'any process that leads to psychological changes of a relatively lasting nature and which are not due to genetic-biological conditions such as maturation or ageing'. According to Illeris (2002), learning always consists of two integrated processes of interaction and internalisation and simultaneously comprises a cognitive, an emotional-psychodynamic and a social/societal dimension.

Three types of processes can be identified in the continuing adaptation process of construction and reconstruction, of which the internal psychological aspect of learning consists (Illeris, 2002):

Cumulative processes: occur whe n learners don’t posses a scheme to which environmental impressions can be related yet. It is about learning things that cannot be connected with previous knowledge. Examples are ‘old-fashioned learning’ such as lists of vocabulary (low transfer possibilities).

Assimilative learning: New impressions are modified and integrated into previously established structures (broader transfer possibilities).

Established structures are reconstructed through dissociation, liberation and reorganisation in accommodative learning; a demanding process. Reflection is a particular form of accommodation; critical reflection is even more demanding: the validity of the presuppositions for previously acquired understandings is assessed.

Transformative learning is a special and very demanding type of learning that occurs in crisis-like situations, which can only be solved by transcending the premises of a

problem or situation. Strong motivation is required, in addition to the ability to raise considerable psychological resources. Transformative learning involves simultaneous restructuring of cognitive as well as emotional schemes and changes the learner’s self and provides him/her with qualitatively new understandings and patterns of action.

The further down the list, the stronger the required motivation. This indicates how Illeris perceives the cognitive and emotional component working together. This means that Illeris presumes the totality of the two internal psychological dimensions (cognitive and emotional) to be in interaction with the social-societal dimension. This interaction consists of direct interaction between people and the individual’s interaction with the material, the societal and the mediatransmitted world, including societal socialisation.

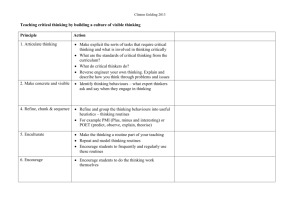

Figure 1: The interaction between dimensions in the tension field of learning (Illeris, 2002). cognition emotion acquisition interaction sociality

For each dimension underlying aspects (variables) can be identified, of which the role and importance in the learning process of SVET students can be examined, as well as the intera ction with the other dimensions. For instance, ‘does reflection (accommodative process of the cognitive dimension) occur and how does this interact with the emotional- and as a totality with the socialsocietal dimension?’ Perhaps only assimilative learning processes are identified; perhaps the emotional dimension plays an important role in the appearance of resistance.

Indicators for these processes and interactions in the learning activities of SVET students need to be identified, in order to be able to describe the learning processes that take place during

WPL.

Based on this theoretical model, 12 students are observed during their first apprenticeship period. 6 students in a caring course and 6 students in a retail course, each equally divided in work based and school based trajectories. By observing work activities (and implicitly learning activities) and mentoring meetings and by interviewing students and their mentors and teachers, detailed, qualitative information is gathered and the learning process is reconstructed backwardly (first the outcome is assessed, then the learning process is reconstructed). First conclusions, based on a in depth analysis of one student, show that the impact of college mentoring is minimal; the practical mentoring is based on fading scaffolding and modelling: at first instance the student only observes her model; in second instance she is allowed to act under supervision; in third instance she is allowed to act rather independently. Improvement of action patterns happens without much reflection. Students act as employees as soon as

possible. Becoming a member of the community is an important objective. Explicit learning activities are seen as annoying and disturbing. The student has learned by participating in the work processes, but sophisticated abstraction, needed for the development of firm constructs

(Solomon and Perkins, 1989) is absent. Both social interaction as acquisition processes can be seen in the learning process, in coherence with student characteristics and context variables. A comparative analyse on the results of the other 11 students has to be done, in order to formulate a more systematic insight in work based learning processes.

Improving the learning potential of work based learning: design studies

The project of Blokhuis is developed as a design study for effective workplace learning in vocational education. Later on a project is developed on the effectiveness of dual trajectories

(combinations of work based and school based learning) in higher professional education.

Blokhuis, Jellema & Nijhof (2002) present an ample review of the literature on the outcomes of work based learning within vocational education and training programmes. He concludes on eight clusters of variables, having impact on learning results, although the evidence for these results is not always very strong.

Participation: to enhance critical reflective work behaviour (van Woerkom, 2003) it is important that workers/learners perceive that they can participate in workplace decisions.

Interaction: work based learning is enhanced when workers have the possibility to interaction with colleagues within their own community of practice, but also with people from outside (boundary crossing: see Engeström’s work).

Variation: learners/workers should be involved in different aspects of the work process in order to acquire a complete scheme of it (cf. Boreham, 2001).

Complexity: to learn a craft, learners should be confronted with complete tasks: atomizing tasks into simple units is hindering the acquisition of competences.

Support: scaffolding the learning process by foremen or expert colleagues is an important aspect of the learning potential of the workplace.

Preparation: good preparation on the learning aspects of apprenticeships can improve the results of work based learning.

Assessment and reflection: assessment of progress will enhance the learning output of work based learning. Reflective moment with other students will support this.

Consistency: school based courses and work based courses should be intertwined.

Based on this set of variables, a course design is developed and will be tested in 2004. In first instance a pilot study is done, in which the implementation has been done in collaboration with the regional college for VET. In fact this turned out in two implementation stages: first in the college, and later in the firm. This was not successful, so in a second study we chose to leave out the college level and directly to work with firms. The experiment focused on interaction patterns between student and mentors for which a guideline for interaction has been developed.

The experiment has been carried out in a hospital, an ICT-firm and a bank. No experimental effects have been found significantly. A gain in job relevant competencies has been found over the practical period, but this gain was not influenced by the experimental treatment. The nonsignificant results have to be explained by implementation problems: limited use of guidelines and frequent changes of mentors, due to organisational problems, reduced the potential power of the guidelines. A promising result is that the intensity of use of the guidelines seems to result in better mastery of job-relevant competencies. This result matches with the premises of Billett

(1999), that the kind of guidance will determine the quality of workplace learning (for more detailed results: see Blokhuis, 2006).

The same set of variables has been used to assess work based learning in higher professional education (Reenalda, Nijhof, Veldkamp-De Jong & Veldkamp, 2006). In a large scale survey amongst 3 rd years students in a pretest-posttest design improvement on General Work Activities

(according to Jeanneret & Borman, 1995) is measured and related to student characteristics

(big 5, self efficacy, motivation, IQ) and course characteristics (work based versus school based; technics versus health). 887 – 1817 students participated in several data collection moments.

Progress is reported on 4 of 6 GWA’s (social, participative, cognitive and career oriented; not on technical and learning to learn skills). Learning environment characteristics have impact on results, but in interaction with course content (health versus technics). Specified learning targets have positive impact on social and participative competences for technical students but negative impact for health students. Collaborative learning is important in technical studies; self regulative strategies have impact in health studies. For most learning targets, the dimension work based versus school based has little impact. For health students, work based learning has some impact on participative and career oriented skills.

Student characteristics do not have strong impact on competence development; some small effects have been reported. This can be explained by system sampling: students in HPE are selected during their school career.

Preliminary conclusions on the results of Reenalda c.s. are that competence development in

HPE can be influenced by the design of learning environments. Specification of learning targets, organisation of collaborative learning, support of self regulation and work based learning have impact, but in many cases in interaction with course domain. These specifications will be investigated during the second stage of this research project.

Conclusive remarks

The key theme of the research programme “the learning potential of the workplace” turns out to be routine, as defined by Nelson and Winter in 1982 (cf. Becker, 2003). Routines are collective recurrent action patterns, which form the basis of economic behaviour in enterprises. An organisation can be defined as a coherent set of routines. Innovation is seen as the change of this set. Enterprises have to balance between stability of routines (in order to produce efficiently) and innovation of routines (in order to survive the creative destruction of economic competition).

Routines are harnessed by communities of practice: routines form the reification of shared actions and norms in the workplace. Routines are flexible to a certain extent: routines are not fixed prescriptions, but adaptable to instant circumstances. This adaptability is a source of improvement and innovation (cf Nooteboom, 2000). Critical reflective workers (broad learners; cf. van Woerkom, 2003) are pivotal in changing routines within communities of practices, whereas narrow learners are essential in the process of exploitation of routines. Both

‘competences’ are needed for the survival of an economic organisation.

The world of work shows a repetitive pattern of balancing between routines and flexibility: on organisational level, community level and individual level. Changing routines is a matter of unfinished learning: new solutions for working problems are sought until an economic optimum is reached. Quick, workable solutions have more chance to survive then slowly developed, technically optimal solutions (cf. Gielen, Hoeve & Nieuwenhuis, 2004).

Workplace routines should be compatible with professional standards of craft workers and experts. Professional institutions come into the game at this point, including normative discussions. Status, positions and historically gained power are decisive in group processes.

Wenger’s (1998) anthropoligical description of group processes in a community of practice has

an sociological and economic explanatory background. (Which is also the basis of the critique on Wengers romantique elaboration of CoP, 2000).

Seen form a novice perspective, the work practice is overwhelmingly coloured by its economic and institutional power play of experts and group routines. The process of legitimate peripheral participation (Lave & Wenger, 1991) towards a recognised position in the group can be seen as the surrender of individual standards to group standards (praxis shock): by accepting group routines, a position is conquered which allows critical behaviour. These social dynamics are important to understand the impact of skilling trajectories as apprenticeships and internships.

The analysis of Poortman (2007) shows that learning of occupational skills in work based learning has to be understood from the logic of working: apprentices identify with colleagues and clients and not with school and learning. Supportive materials from course and college are neglected and explicit learning activities are avoided. The reflectivity of training activities is depending on the interaction between apprentice and direct mentor. Blokhuis (2006) designed an intervention for this interaction process, but did not succeed yet in full implementation of his design. Reenalda a.o. (2006) reports optimistic first results for key issues for effective design of work based courses. Different trajectories, as apprenticeships and school based curricula, have different consequences for this peripheral participation process. Clusters of variables, having impact on the training process, are coloured with the routine concept.

The lever for improving work based learning has to be found in combining the logic of work with educational professionalism (Saljö, 2003). A single educational, preparatory approach will not be successfully implemented in work organisations. Reflective interaction, collaboration and performance orientation as educational interventions have to be translated into work oriented interventions, in which productivity, efficiency and quality of work are leading issues. The optimisation of skilling trajectories for work and occupations have to be seen as an arena in which educational rationalities and work oriented rationalities have to be intertwined and negotiated. There is still a lot of theoretical and practical work to do.

Literature

Argyris, Ch. & D.A. Schön (1996). Organisational learning II: theory, method and practice.

reading MA:

Addison-Wesley Publishing Company.

Becker, M. C. (2003). The concept of routines twenty years after Nelson and Winter (1982) - A review of the literature.

Copenhagen, Danish Research Unit for Industrial Dynamics. DRUID working paper

No 03-06. (GENERIC)

Billett, S. (2001) Learning in the workplace: Strategies for effective practice , Crows Nest: Allen & Unwin.

Blokhuis, F., M.Jellema & W.J. Nijhof (2002) De kwaliteit van de beroepspraktijkvorming: een onderzoek naar praktijken en ervaringen bij ROC Eindhoven, ( Quality of work based learning; an investigation on practices and experiences at Eindhoven regional college). Enschede: Twente University

Blokhuis, F. (2006 ). Evidence based design of work based learning . PhD study. Enschede: Twente

University.

Bolhuis, S. & P.R.J. Simons (1999) Leren en werken (learning and work). Deventer: Kluwer.

Boreham, N. (2002) Technological and Organizational Development. In: Boreham, N., Samurçay, R. and

Fischer, M., (Eds .) Work Process Knowledge, London/New York: Routledge

Brown, J.S. and Duguid, P. (1991) Organizational Learning and Communities of Practice: Towards an unified view of working, learning and innovation. Organization Science 2, 40-57.

Brown, A. & E. Keep (1999) review of vocational education and training research in the United Kingdom.

Luxembourg: COST A11

Cobbenhagen, J. (2000) Succesfull innovation: Towards a New Theory for the Management of Small and

Medium Sized ENterprises, Cheltenham/Northamton, MA: Edward Elgar.

Dosi, G. (1988) Sources, Procedures, and Microeconomic Effects of Innovation. Journal of Economic

Literature 26, 1120-1171.

Egidi, M. & A. Narduzzo (1997). The emergence of path-dependent behaviors in cooperative contexts. In:

International Journal of Industrial Organization , vol. 15, pp. 677-709.

Ellström, P. E. (2001). Integrating learning and work: Problems and prospects. Human Resource

Development Quarterly, 12(4), 421-435.

Engeström, Y., Miettinen, R. and Punamä, R.L. (1999) Perspectives on Activity Theory , Cambridge:

Cambridge University Press.

Eraut, M. (2000) Non-formal learning and tacit knowledge in professional work. British Journal of

Educational Psychology.

70, 1, 113-136.

Eraut, M., J. Alderton, G. Cole & P. Senker (1998) Development of knowledge and skills in employment.

East Sussex: University of Sussex.

Garrick, J. (1998). Informal learning in the workplace. Unmasking human resource development . London:

Routledge.

Gielen, P. and Hoeve, A., (2002) Een reden om te leren?

Wageningen: Stoas Onderzoek.

Gielen, P., Hoeve,A. & Nieuwenhuis, L. (2003), Learning Entrepreneurs: Learning and Innovation in

Agricultural SME, In: European Educational Research Journal , vol. 2, no. 1, pp. 90-107

Harris, J. R. (1999), Het misverstand opvoeding: Over de invloed van ouders op kinderen. (Dutch translation from: The Nurture Assumption: Why children turn out the way they do ),

Amsterdam/Antwerp: Uitgeverij Contact

Heiner R.A. (1983). The origin of predictable behavior. In: The American Economic Review . Vol. 73, no.

4, pp. 560-595.

Hoeve, A. and Nieuwenhuis, L. (2002) Learning in Innovation Processes . Paper presented at the ORD

May 29-31 2002 in Antwerp, Belgium.

Hoeve, A. & Nieuwenhuis, L. (2003), Innovation and Learning in Practice: Testing a research model – paper gepresenteerd op het EARLI congres, 2530 augustus, 2003 te Padua, Italië.

Hoeve, A. & L.F.M. Nieuwenhuis (2006) Learning routines in innovation processes. Accepted by Journal of Workplace Learning.

Illeris, K. (2002 ) The Three Dimensions of Learning: Contemporary Learning Theory in the Tension Field between the Cognitive, the Emotional and the Social , Frederiksberg: Roskilde University Press.

Jeanneret, P.R. & W.C. Borman (1995) Generalized work activities. In: N.G. Peterson, M.D. Mumford,

W.C. Borman, P.R.Jeanneret & E.A. Fleishman (eds) Development of a prototype Occupational

Information Network content model. Salt Lake City: Utah department of employment security.

Jorna, R. and Heusden, B. van (2000), Cognitive Dynamics: A Framework to Handle Types of

Knowledge. In: Schreinemakers, J.F., (Ed.) Knowledge management: proceedings of the Seventh international ISMICK symposium.

pp. 128-145p. Rotterdam: Rotterdam University Press.

Kwakman, K. (1999) Leren van docenten tijdens de beroepsloopbaan: Studies naar de professionaliteit op de werkplek in het voortgezet onderwijs . Katholieke Universiteit Nijmegen.

Lave, J. and Wenger, E. (1991) Situated Learning; Legitimate Peripheral Participation , Cambridge:

Cambridge University Press.

Lindley, R.M. (2003) Knowledge-based economies: the European employment debate in a new context.

Invited address for the seminario in memoria di Ezio Tarantelli, Roma, sept. 24th 2003. Warwick:

Institute for Employment Research.

Marsick, V.J., & Watkins, K.E. (1990). Informal and incidental learning in the workplace . London:

Routledge.

Marsick, V. & M. Volpe (1999) Informal learning on the job.

In: Advances in developing human resources, nr. 3. San Francisco: Berret-Koehler.

Mayer, K. (2002). Vocational education and training in transition:from Fordism to a learning economy. In:

W.J. Nijhof, A. Heikkinen & L.F.M. Nieuwenhuis (eds): Shaping flexibility in vocational education and training.

Dordrecht/Boston/ London: Kluwer Academic Publishers.

Mittendorff, K. (2003 ) Tapping Labor's Brains: a research on collective learning and communities of practice . University of Nijmegen.

Munby, H., J. Versnel, N.L. Hutchinson, P. Chin & D.H. Berg (2003). Workplace learning and the metacognitive functions of routines. In: Journal of workplace learning, vol. 15, no. 3, pp. 94-104.

Nieuwenhuis, L.F.M. & M. van Woerkom (2007). Goal rationalities in work related learning. In HRD

Review, jrg. 6, no. 1. pp. 64-83.

Nieuwenhuis, L.F.M. (2004) Parallelliteit van leren en werken. In: J.N. Streumer & M. van der Klink: Leren op de werkplek.

Den Haag: Reed Business Information.

Nieuwenhuis, L. & C. Poortman (2009). Praktijkleren in het beroepsonderwijs. In: R. Klarus & PRJ Simons

(eds). Wat is goed onderwijs? Bijdragen uit de psychologie.

Den Haag: Lemma.

Nijhof, W.J., A. Heikkinen & L.F.M. Nieuwenhuis (eds. 2002) Shaping flexibility in vocational education and training; institutional, curricular and professional conditions.

Dordrecht/Boston/London: Kluwer

Academic Publishers.

Nijhof, W.J. & L.F.M. Nieuwenhuis (eds. 2008) The learning potential of the workplace.

Rotterdam/Taipei:

Sense Publishers.

Nonaka, I. and Takeuchi, H. (1995) The Knowledge Creating Company: How Japanese Companies

Create the Dynamics of Innovation , Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Nooteboom, B. (2000) Learning and Innovation in Organizations and Economies, Oxford: Oxford

University Press.

Nooteboom, B. (1996) Towards a Cognitive Theory of the Firm: Issues and Logic of Change , Groningen:

University of Groningen - SOM Research Institute.

Poortman, C.L., W.J. Nijhof & L.F.M. Nieuwenhuis (2004) Workplace learning processes in secondary vocational education and training. Workplace learning from the learners’ perspective. Copenhagen:

Learning lab. ( http://wl-conference2004.lld.dk/home.html

)

Poortman, C.L., W.J. Nijhof & L.F.M. Nieuwenuis (2006). Zorgen voor leerprocessen in beroepspraktijkvorming (caring for learning in work based learning). Accepted for publiciation in

Pedagogische Studiën.

Poortman, C.L. (2007). Workplace learning processes in Senior Secondary VET.

PhD. Enschede: Twente

University.

Reenalda, M., W.J. Nijhof, R.J. Veldkamp-de Jong & B.P. Veldkamp (in press). De effecten van duale leeromgevingen in het HBO (impact of dual learning environment in HPE).

Accepted for publiciation in Pedagogische Studiën.

Saljö, R. (2003). Epilogue: from transfer to boundary crossing. In: T. Tuomi-Gröhn & Y. Engström (eds).

Between school and work; new perspectives on transfer and boundary crossing . Amsterdam/Boston:

Pergamon.

Salomon, G. and Perkins, D.N. (1998) Individual and Social Aspects of Learning. Review of research in

Education 23, 1-24.

Schank, R.C. and Abelson, R.P. (1977) Scripts, Plans, Goals and Understanding: An Inquiry into Human

Knowledge Structures , Hillsdale, NJ.: Lawrence Erlbaum.

Senge, P.M. (1990) The Fifth Discipline: The Art & Practice of the Learning Organization , New York:

Doubleday.

Simons, P.R.J. & M. Ruijters (2001) Work related learning: elaborate, expand and externalise. In: W.J.

Nijhof & L.F.M. Nieruwenhuis (eds). The dynamics of VET and HRD systems . Enschede: Twente

University Press.

Stasz, C. & T. Kaganoff (1997) Learning how to learn at work: lessons from three high school programs .

(report no. MDS-916). Berkeley, CA: national centre for research in vocational education, University of California at Berkeley.

Taylor, F.W. (1911). The principles of scientific management . New York: Harper Bros.

Weick, K.E. (2001) Making Sense of the Organization, Oxford [etc.]: Blackwell Publishers.

Wenger, E. (1998) Communities of Practice: Learning, Meaning and Identity, Cambridge: Cambridge

University Press.

Wenger, E., McDermott. R. and Snyder, W.M. (2002) Cultivating Communities of Practice: A Guide to

Managing Knowledge, Boston, MA.: Harvard Business School Press.

Woerkom, M. (2003) Critical Reflection at Work: Bridging Individual and Organisational Learning.

Twente

University.