One Hundred Years of Agriculture, the Giant side of Lubbock, by

advertisement

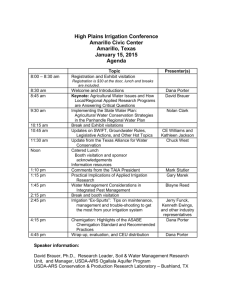

One Hundred Years of Agriculture – the Giant Side of Lubbock by the Lubbock Chamber of Commerce Agriculture Committee's Centennial Subcommittee The Census of 1890 reported that 33 people lived in Lubbock County, and the first big wave of settlers arrived in the late summer prospecting for land. Thousands of acres of land on the South Plains were placed on the market by the State – with low prices and easy purchase terms- the beginning of what historians have termed the “Farmer’s Frontier.” People were lured to West Texas by favorable land laws and fertile soil. Lubbock was founded as a part of the movement westward onto the High Plains by ranchers and farmers. At the turn of the century, there were about 300 people in the county, most of whom lived in the town of Lubbock. The town’s growth cannot be separated from the growth of the area, which was primarily due to the development of agriculture. With the main asset being land, the emphasis changed from stock raising to farming. By 1905, the Lubbock area was a land of well tilled farms which produced a wide variety of crops. And in 1908 the newspaper reported that most of the citizens believed “the big herds (of cattle) are a thing of the past…Farming is of as much or more importance to us now as the cattle business was a few years ago.” Ranching had been big business in terms of the money invested and extensiveness of the operations. But, increasing land values caused land to become too valuable to use for pasture. The land owners divided their acreages and sold them for handsome profits to farmers and smaller plot operators. By the beginning of the century scarcely a dozen years after the first bale of cotton was ginned west of Abilene, Texas, cotton was also being produced in Lubbock County. The first verified cotton crop was in the census of 1900 indicating that Lubbock County produced fifteen bales of cotton on twenty acres. In 1903, 47 bales were produced, and in 1904, 110 bales in production more than doubled the previous year’s crop. In 1904 the Lubbock townspeople joined together to initiate and fund the building of a gin in Lubbock, marking the beginning of Lubbock as a cotton center. Seven hundred bales were ginned in Lubbock the following year. With a population of about 1,800 the town had no municipal government, no water or sewer lines, no fire or police departments or other well established “city services.” On March 16th, 1909 an election was held, and eighty-four votes were cast in favor of incorporation and the City of Lubbock was born. Leading citizens influenced the decision of the Santa Fe Railroad to extend the railway from Plainview to Lubbock, and by October of 1909 the rail line was fully opened for passenger and freight service-expanding the opportunities for Lubbock to become a central marketing “hub.” Also in 1909, as a primary result of the efforts of the Lubbock Commercial Club (predecessor of the Chamber of Commerce) the Texas Agricultural Experiment Station-Substation No.8 of the Agricultural and Mechanical College of Texas was opened near Lubbock to serve the growing agricultural community. The base of the Lubbock economy was rooted firmly in agriculture. In 1910, Lubbock County had 277,269 acres in farms and ranches representing 49.9 percent of the available land in the county. By 1911, over 600 bales of cotton were grown in the immediate Lubbock area. Speculation into irrigation wells had started in the early 1900’s and although windmills speckled the plains, there was no significant irrigation except for gardens. The first relatively successful irrigation well in Lubbock County was on the B.O. McWhorter Ranch in early 1911. There were other successful wells on the Sunshine Ranch, St. Augustine School Land and George Boles Farm. These early wells had tapped the Ogallala formation proving that this water supply could banish the fears of drought, and help lure more settlers to the potentially profitable farming area. In the early 1920’s Lubbock aggressively sought to obtain Texas Tech, which was envisioned by many as a “farm school.” Texas Technological College was opened in 1925 and the first year of operation enrolled 1,379 students “to give instruction in technological, manufacturing, and agricultural pursuits” – as claimed by Senate Bill 103 establishing the college. The first four schools of the college were Agriculture, Engineering, Home Economics, And Liberal Arts. By 1924, Lubbock County produced over 41,000 bales of cotton on 136,000 acres. The rapid division of land parcels lasted over a period of years, and the last big roundup of cattle on the North Spade Ranch took place in the spring of 1925 when over 5,800 head of cattle were driven from 90,000 acres. The flourishing agricultural industry served as an incentive for more immigration into Lubbock and city officials did not miss out on the opportunity to encourage new growth in population and the Lubbock Chamber of Commerce initiated an advertising campaign in 1927 to draw agricultural production and population into the area. The Chamber devoted $100,000 to the drive which lasted over a three year period, and was deemed a success in 1930. The Lubbock area of West Texas was one of the last vestiges of the American frontier but agriculture provided the catalyst for settlement and growth. Crop and animal production along with agricultural processing, distribution, transportation, support services and supplies, created the largest single economic force within the South Plains. From the handful of cotton bales produced those very early years, cotton production grew to 100,000 bales by 1932. With large-scale crop production came mechanization, irrigation technology and agriculture research, and the cotton-stripper was developed in 1926 for use in the High Plains. The railroads opened an important era for the growth of Lubbock. With the railroad came people and with people, a need for education. Texas Technical College, now known as Texas Tech University, was declared in 1923. The Future Farmers of America was founded in 1928 and was the first organization to teach young students about agriculture. The Panhandle South Plains Fair was established in 1920 and still runs every fall. Burrus Elevators was constructed in 1927 and was the first large grain storage facility in Lubbock, and the first successful oil well was drilled in 1929. But dark clouds gathered as agricultural surpluses and the collapse of agricultural prices in the late 1920s, brought long-term agricultural depression lasting from 1921 to 1940, with the worst of the Great Depression hitting in 1932. While emerging from the Great Depression and recovering from the strains of World War II, agricultural production once again took a strong stand in Lubbock. The diversified agriculture industry primarily included the production of wheat, sorghum, cotton, cattle, hogs, sheep and chickens. Farmers were encouraged to produce a variety of crops, foregoing their conceptions of single crop farming. Although strongly encouraged to do so, the number of farmers implementing a multi-crop farm has significantly dwindled since the 1940s. Individual farmers acquired more land and larger machines were needed to work their farms. The times of the oxen pulled plow and hand-picked cotton were fading, only to be overridden by rubber-tired tractors and the invention of the tractor-mounted cotton stripper. The newer and bigger equipment had the ability to multiply the amount of work done by a single person. These technological advances made farming more efficient and profitable. Suddenly, Lubbock area farms saw a drastic rise in their productivity. Although farms were getting larger, the weather was never predictable; therefore, water was always an issue. With the Ogallala aquifer lying below the surface, furrow irrigation was the primary means of watering the crops in the Lubbock area. In 1951, the High Plains Underground Water District was developed with the task of conserving, preserving, protecting and preventing the waste of underground water from the Ogallala aquifer. With water from the underground aquifer, the residents of the Lubbock area produced a crop of four million acres of cotton in 1952, valued at more than $32 million. Agriculture served as the hub of the economy of Lubbock. In 1950, 25% of the residents of Lubbock County resided on farms. Urbanization had not yet come to the city and most businesses survived with the agricultural industry serving as the backbone of community. The 1960's and 70's brought about changes and advancements in agriculture that would shape the face of agriculture, not only in Lubbock Texas, but across the nation. In 1960, cotton apparel and home furnishings accounted for about 78 percent of the textile production. With the introduction of synthetic fibers around 1975, that percentage plummeted to 34 percent threatening cotton's extinction as a viable commercial commodity. Producers of the High Plains called for a collective national marketing and research effort. Those cotton growers were successful in petitioning Congress into passing the Cotton Research and Promotion Act of 1966. This act established funding mechanisms based on producer assessments for the purpose of conducting wide scale efforts to recapture cotton's market. This initiation in funding mechanisms led to the creation in 1970 of Cotton Incorporated. Cotton Incorporated promotes cotton fabrics globally. Another creation that shaped agriculture as we know it is the invention of the cotton module builder. Before its creation, cotton farmers would either harvest their cotton by hand using workers, or with a mechanical device known as a cotton stripper. The cotton would go up a chute to a basket, which when full, would be emptied into trailers. Workers would tromp the cotton to get the maximum amount of cotton the trailers. When the trailers were full, the farmers would transport them to the gins. They would leave the trailers on the gin yard. Production at the gins would get backed up with all the cotton coming in and they would not get to the trailers sometimes for a week or more. With all a farmer’s trailers at the gin yard, his harvesting operation would come to a standstill. Realizing that there had to be a better way to manage a harvest, Cotton Incorporated collaborated with Texas A&M University and Texas Tech University on a program to develop a superior seed cotton handling system. This three-year program, begun in 1971 and led by Professor Lambert Wilkes of the Texas A&M Department of Agricultural Engineering, produced the prototype for the first module builder. The primary hurdle for development of the module builder was proving that seed cotton could be compacted and would remain compacted through transport. Early experiments were successful; the system was perfected through numerous trials. These days, the module builder is a staple of the industry and for good reason. Currently, over 90% of the U.S. cotton crop is managed through the use of module builders. Although the invention of the module builder was a great asset to the cotton farmer, there needed to be a machine that could haul the modules to the gins at a reasonable pace. Barry Reynolds of Lubbock envisioned the idea of a truck that could pick up modules and take them to the gins. With this invention, a module containing the equivalent of 10-15 bales of unprocessed cotton could be loaded on a truck within minutes and transported to the gins. This opened the door to the development and adoption of higher speed ginning equipment. Another advancement implemented in the South Plains was the creation of grain sorghum hybridization. It helped answer the rising demands of the cattle feeding industry on the High Plains. Cattle thrived in this area and locally produced feed grains supply was greater than demand. By the 1960's entrepreneurs and promoters conceived the idea of combining resources to prepare beef animals for slaughter. By the end of the decade, large feedlots were now capable of handling several thousand animals. In the early 1970's, more than 3 million head were being marketed annually. With about 70 percent of cattle being fed on the High Plains, the Lubbock area became a leader in fed cattle production in the nation. The 1970's were a relatively prosperous agricultural period for Lubbock and its farmers. However, farmers in the 1980's were about to face the toughest economic times in the history of agriculture, short of the dust bowl days and great depression of the 1930's. Interest rates began climbing in the late 1970's and by the early 1980's, the cost of borrowing money was well above 20%. This, coupled with depressed prices, several years of poor crop and all-time high land prices resulted in farmers struggling under heavy debt. Land prices peaked in the early 1980's before a decline began. By 1985, land values had dropped in half, eroding equity and the ability for many farmers to continue operating. As the agriculture community worked through these problems, programs were developed during this time period such at the Conservation Reserve Program. This program greatly improved soil conservation practices by taking the more highly erodible land out of production and helping to reduce the severity of water erosion and dust storms. By the mid 1980's, interest rates had began to fall and the farming community began to slowly recover from its economic downturn. Many consider the period from the 1980's to the present time to be the period that witnessed the greatest improvements in farming technology since mechanization. One of the most important technological advancements made in that time was in the area of crop irrigation. The practice of row watering crops was considered inefficient, and wasteful of water resources. In the early 1980's, Dr. Bill Lyle, with the Texas A&M Research Center in Lubbock, pioneered and developed the concept of low energy precision application, or LEPA center pivot irrigation systems. These systems, designed to work under low water pressure, utilized drop hoses, low pressure nozzles and drag hoses and became widely accepted on the South Plains. Today, the term LEPA is a household word in the irrigation industry world-wide. Center Pivot irrigation systems numbered a little over 3,000 in 1986, and by 2005 a total of 12,238 systems were operating on the High Plains. Drip irrigation, a system for underground crop irrigation, was also developed during this time period, and irrigation efficiency improved from 50% in the early 1980's to 95% and even greater today, thus helping to save our underground water resources for future generations. Cotton production has continued to climb as improvements in farming technologies were made. Improvements in cotton genetics have resulted in increased production since cotton was first commercially produced on the South Plains. The period from 1995 to today has witnessed the most dramatic increases in yields due to cotton variety enhancements. Today the region surrounding Lubbock produces 4 million, or more, bales of cotton annually from 3 million harvested acres, or 23% of the total US cotton crop. Due to these improvements in cotton genetics and irrigation, the average yield per acre has increased from around 150 pounds per acre in the 1930's, to a 786 pound per acre yield for the 2005 crop year. Today, Lubbock is well known as one of the world’s largest agricultural producing regions, and is home to many agricultural organizations recognized both nationally and world-wide. Institutions conducting agricultural research in Lubbock such as Texas Tech University’s College of Agricultural Sciences and Natural Resources, The International Textile Center at Texas Tech, the Texas Agricultural Experiment Station and Cooperative Extension, The High Plains Underground Water Conservation District and the USDA-ARS Plant Stress Lab in Lubbock continually work to improve agriculture for this region and the nation, and insure Lubbock's place as a world-class leader in agricultural development and research. There is little question that the economy of Lubbock is squarely based on agriculture. The 20 county retail trade area surrounding Lubbock reported $3.4 billion in cash value of basic agricultural production in 2005. While the economy of the city has certainly become more diverse since the early pioneer days, the foundation has and always will be, agriculture. Back in 1849, US Army Capt. Randolph B. Marcy, on a reconnaissance mission through this area described it as part of a vast desert prairie … “a land which always has been, and always must continue uninhabited forever.” Today, the Southern High Plains, with Lubbock at its hub, has proved Capt. Marcy wrong. It has become, without question, one of the most productive agricultural regions in the United States. ============================= Water-related History by Lubbock Chamber of Commerce Ag Committee's Centennial Subcommittee It started with windmills.... The Texas High Plains region, once known as the “Great American Desert,” was believed to be incapable of sustaining life. Yet, early settlers saw this semi-arid region with its nearly-flat land as a special place with great opportunities. They saw a sea of stirrup-high grasses, plenty of elbow room, and clear fallow land to farm. They found buffalo chips and saw fuel. They found playa lakes and saw watering holes and homesteads. With that vision, they toughed it out through droughts, blizzards, and dust storms, and turned the High Plains into one of the most productive agricultural regions in the United States. All of this could not have been accomplished without hard work and access to a reliable water supply. “The windmill was the most important tool of the development of this area,” said Coy Harris, executive director of the American Wind Power Center in Lubbock. “It was the only way people could come out here to live.” Once the settlers arrived, they soon realized that they had to use ground water to supplement the 18 to 20 inches of rainfall that the region receives each year. Use of self-governing windmills provided homesteaders easy access to ground water. A windmill and tower could be purchased for about $25 during the 1870s and 80s. These windmills were portable and could be hauled and placed anywhere. In addition, the region was blessed with an ample supply of wind for power. Even though windmills allowed easier access to ground water for domestic use, there were few developments in irrigation technology at that time. The first successful commercial irrigation in the area occurred more than 90 years ago in Portales, New Mexico. It wasn't long before businessmen from the Texas High Plains traveled across the state line to see the newfangled technology. 1910-1920 The first irrigation well in Bailey County was dug in 1909. According to an early issue of a Plainview newspaper, the first successful irrigation well in that area was drilled in January 1911 on the J.H. Slaton farm, four miles west of Plainview. During that year, six or seven additional irrigation wells were drilled. According to the Southwest Collection, Don H. Biggers dug one of the first irrigation wells in Lubbock, Texas, in 1911. At a depth of 112 feet, the Earhart well used a 25 horsepower engine to pump water to the surface. During the first few years, the well proved to be a minor success but after Biggers sold the property, output increased and the well provided a constant supply of water. In 1912, Dr. Frederick Pearson of New York organized a syndicate known as the Texas Land and Development Company. It purchased 60,000 acres of land near Plainview and began development of large scale ground water irrigation. By 1913, the company had drilled and equipped 85 irrigation wells. By 1914, it was reported that there were 139 irrigation wells in the Texas High Plains. There were 100 in the Plainview vicinity, in eastern Hale County, western Floyd County, and southern Swisher County; 27 were located near Hereford and southeastern Deaf Smith County; and 12 near Muleshoe, northeastern Bailey County, and northwestern Lamb County. Company records in 1918 show 160 irrigation wells in the Plainview area. Of these, 127 had been equipped by the company and 33 by individual land owners. 1920-1930 During World War I, there was a general decline in water well irrigation, due in part to the shortage of materials, high cost of labor, and introduction of the tractor which encouraged cultivation and cropping of large tracts using dryland methods. In the seven years following the war, (1919-1926), the area had above average rainfall and very little irrigation was used. 1930-1940 However, interest was revived after several years of low rainfall. The number of irrigation wells on the High Plains jumped from 296 in 1934 to 310 in 1939. After the “Dust Bowl” and World War II, there was another surge in irrigation. Early irrigators used open discharge wells to deliver water to the field. They drilled these wells on the high point of the field and used ditches to transport the water, where it was released between borders on what was called “lands”. Later, siphon tubes were used to deliver the water to the furrows. This practice allowed considerable water losses from evaporation and deep percolation. During this time, many believed the myth that great underground rivers flowed freely from the Rockies to the High Plains providing a never-ending water supply. Some folks from downstate said we used water too freely; they saw it as a waste of a valuable commodity and introduced bills into the state legislature to declare underground water in Texas as property of the state. Area residents opposed such regulation. W. L. (Bill) Broadhurst (now 102) recalls telling area leaders that “...I think you know that one of these days, there's going to be a law passed regulating the use of groundwater, so why don't you get together and propose something you can live with; something that you think ought to be groundwater law in Texas.” Local attorneys began drafting legislation that would become the Groundwater Conservation Districts Act of 1949. A 1930s Works Progress Administration (WPA) project dredged Yellowhouse Draw near the 10-acre Lubbock Lake in an attempt to rejuvenate springs on the west side of the lake. Two teenagers found a Folsom spear point during the dredging, which they took to Texas Tech history professor William Curry Holden. He realized the significance of this find and began taking steps to protect the Lubbock Lake site. Its archeological riches exist today because of a reliable water supply that attracted people and wildlife to the site for centuries. The water in Yellowhouse Draw appealed to pioneers like George Singer, who established the first known trading post at the site in 1883. 1940-1950 During this time, furrow irrigation, using siphon tubes, was the primary method of providing irrigation water to crops in the region. Water was transported to the field in open, unlined earthen ditches. Water losses often equaled 50 percent of the total water pumped onto the field. The Groundwater Conservation Districts Act of 1949 was passed by the state legislature. Area voters created the High Plains Underground Water Conservation District No. 1 in September 1951. The district, headquartered in Lubbock, is the first groundwater conservation district created in Texas. It was created to conserve, preserve, protect, and prevent the waste of underground water from the Ogallala aquifer in a 15-county service area. 1950-1960 Underground pipelines rapidly replaced open ditches in the 1950s and 1960s, eliminating a significant portion of water losses to deep percolation, seepage, and evaporation from open ditches. By 1958, there were 44,000 irrigation wells in operation and that number has jumped to more than 57,000 permitted wells in 2007. 1960-1970 During the 1960s and 1970s, irrigation tailwater return systems were installed on a high percentage of farms in tighter soil (clay) areas to reclaim previously lost irrigation water (“tailwater”). A later 1991 inventory would show 1,444 tailwater return systems and 1,289 modified playa basins in use within the district. During this same time, high pressure and side roll sprinkler systems were used to irrigate the sandy soils of the region. These systems had water losses of about 50 percent from the small drops of water sprayed high above the crops and from the surface of the soil and plant canopy. Marvin and Mildred Shurbet, a Floyd County farm couple, sued the Federal Government claiming a right to a tax credit for the depletion of the groundwater they were “mining” in their business of agriculture. Water District attorneys filed the petition in 1961 after the IRS agreed to allow the lawsuit as a test case. It came to trial in January 1962 and the decision in favor of the Shurbets was announced in January 1963. The Federal Government appealed and the suit was settled in 1965. The ruling saved area taxpayers from three to five million dollars a year initially in cost-depletion deductions. 1970-1980 The High Plains Underground Water Conservation District No. 1 and the USDA-Soil Conservation Service developed field mobile water conservation laboratories containing the necessary equipment to analyze irrigation application efficiencies. The irrigation management teams identified some common problems and were often able to assist irrigators in improving their irrigation application efficiencies an average of 15 percent. In the early 1980s, high pressure center pivot systems began to be modified or replaced with center pivot sprinkler systems equipped with drop lines to discharge water at a lower pressure, with a larger drop size, at about four feet above land surface. This helped reduce water losses from 50 percent to about 20 percent. During the 1980s, Dr. Bill Lyle with the Texas A&M Research and Extension Center at Lubbock pioneered and developed the concept of low energy precision application (LEPA) of irrigation water from center pivot and traveling linear irrigation systems, which made the adoption of the combination of low pressure drop nozzles, coupled with furrow dikes, widespread throughout the High Plains and the term, “LEPA,” a household word in the irrigation industry throughout the world. In 1983, time-controlled surge valves began to be added to the underground pipe systems used to provide water for furrow irrigation. These surge valves provided a method to alternate the flow of water down two sets of furrows on a timed sequence. Their addition reduced or eliminated deep percolation and tailwater. Water losses were reduced to about 20 percent. During the late 1980s and early 1990s, many partial drop center pivot sprinkler systems (Low Elevation Spray Application or LESA) were further modified to deliver water into the furrow with either drag socks or drag hoses (Low Energy Precision Application or LEPA). Drip irrigation was being considered by many researchers as a practice adaptable to the Texas High Plains region. Drip irrigation is primarily used in greenhouses, gardens, and orchards. However, its application is being researched for extensive use on other crops, such as cotton. 1990-2000 An April 19, 1991 groundbreaking ceremony signals the beginning of construction on the John T. Montford dam, which will impound the Double Mountain Fork of the Brazos River to create Lake Alan Henry. Three 10-acre drip irrigation demonstration plots were established by the High Plains Water District for a five-year project in Lubbock, Hockley, and Lynn Counties in 1991. The 1991 cotton crop was plagued with hardships. After an uncertain start, the prospects looked good until a cold front swept across the area in June, causing temperatures to drop 30 degrees. About 60-65 percent of the region's cotton crop had to be replanted. After replanting, the crop then endured the worst aphid infestation to hit the Texas High Plains. Warmer weather in September prompted re-growth of cotton plants at a time when the plants should have been developing bolls. The proverbial “nail in the coffin” came with a sudden hard freeze, accompanied with moisture, on Oct. 28. Temperatures dropped to a low of 7 degrees Fahrenheit and remained below freezing from Oct. 28 to Nov. 1. The High Plains Underground Water Conservation District tests the use of potential evapotranspiration data to improve irrigation scheduling within its service area. Drought conditions occurred throughout the area in 1996 and 1998. The state-of-the art Cropping Systems Research Laboratory opened in 1999. The laboratory's goals include moving stress protection genes into plant germplasm, and introduction of “precision agriculture” to help farmers make decisions as to when, where, and at what rate to apply irrigation water, fertilizer, and pesticides. 2000-Present Hail, high winds, and blowing sand from four severe storms dealt a hard blow to High Plains producers during May and June 2001. A May 30 storm with damaging hail and high winds tracked along Highway 84 from Clovis NM to Snyder, TX. Crops, livestock, barns, houses, and equipment in nine counties were damaged as a result of this storm. The highest recorded wind gust associated with this storm was 105 miles per hour at the Reese Technology Center, in West Lubbock. The West Texas region saw the harvest of two back-to-back cotton crops. Much of the success can be attributed to new technologies in seed varieties and abundant rainfall during 2004 and 2005. However, producers were concerned about drought conditions that plagued them throughout most of the 2006 growing season. Reduced rainfall, due to drought, high temperatures and wind, low humidity, and abovenormal water use combined to bring surface water levels in Lake Meredith to a historic low level. House Bill 1763, passed in 2005, requires water conservation districts to develop desired future conditions (DFC) for aquifers within their groundwater management areas. The respective groundwater district managers and representatives are now working to develop these DFCs. The Texas Alliance for Water Conservation is conducting an eight-year study to identify and quantify the best agricultural production practices and technologies to reduce groundwater pumpage from the Ogallala aquifer, while maintaining agricultural production and economic opportunities. Approximately 12,238 center pivot sprinkler systems are currently operating within the High Plains Underground Water Conservation District No. 1, according to a November 2005 survey. There were 743 pivots irrigating 94,961 acres in Lubbock County in 2005. Summary Irrigation has undergone many changes and advancements throughout the years. Production of irrigated products remains the backbone of today's regional economy due to new research, organizations that deliver new technologies to producers, and the producers' willingness to adopt the new techniques to prolong the life of the Ogallala Aquifer.