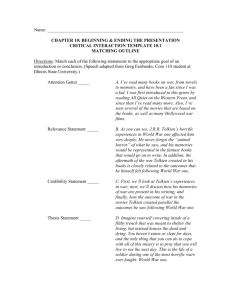

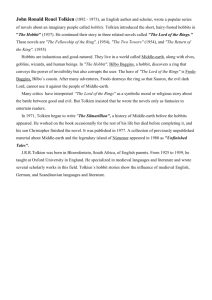

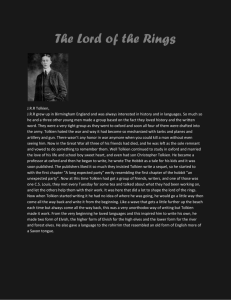

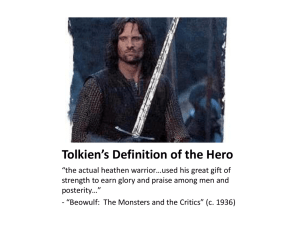

How To Read The Silmarillion

advertisement