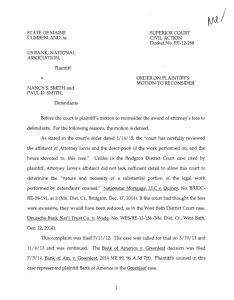

Readings for June 13 - Unified Court System

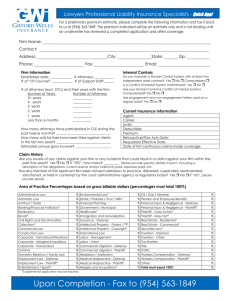

advertisement