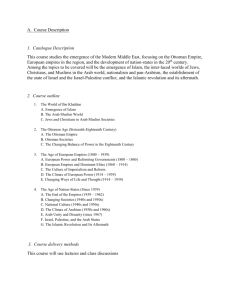

Word

advertisement

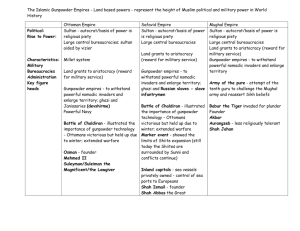

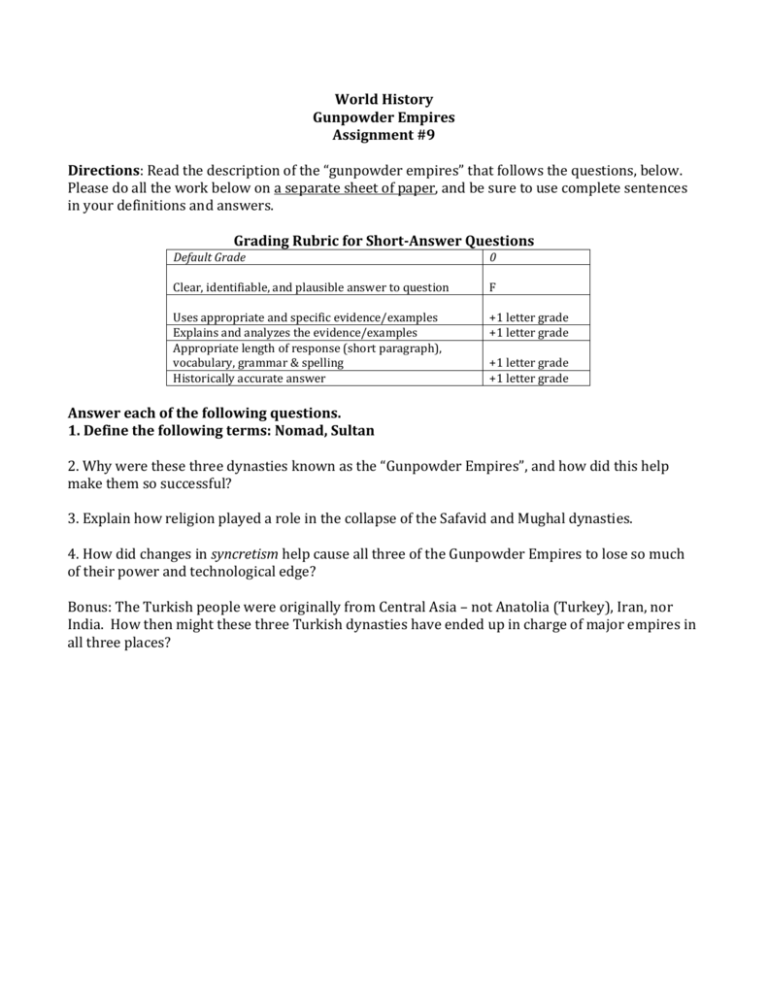

World History Gunpowder Empires Assignment #9 Directions: Read the description of the “gunpowder empires” that follows the questions, below. Please do all the work below on a separate sheet of paper, and be sure to use complete sentences in your definitions and answers. Grading Rubric for Short-Answer Questions Default Grade 0 Clear, identifiable, and plausible answer to question F Uses appropriate and specific evidence/examples Explains and analyzes the evidence/examples Appropriate length of response (short paragraph), vocabulary, grammar & spelling Historically accurate answer +1 letter grade +1 letter grade +1 letter grade +1 letter grade Answer each of the following questions. 1. Define the following terms: Nomad, Sultan 2. Why were these three dynasties known as the “Gunpowder Empires”, and how did this help make them so successful? 3. Explain how religion played a role in the collapse of the Safavid and Mughal dynasties. 4. How did changes in syncretism help cause all three of the Gunpowder Empires to lose so much of their power and technological edge? Bonus: The Turkish people were originally from Central Asia – not Anatolia (Turkey), Iran, nor India. How then might these three Turkish dynasties have ended up in charge of major empires in all three places? The Gunpowder Empires Steve Muhlberger After the collapse of the Timurid dynasty in the early 1400s, Islamic politics changed quite a bit. Later dynasties were much more stable, much more identified with a particular piece of territory, and much more involved in the life of the local communities that made them up. There seem to be two reasons for this. First, cities and farming culture were continuing to spread. This is precisely the period when much of what is now Russia, for instance, ceased to be dominated by nomadic herders and began to be dominated by peasants and their landlords. More and more, formerly nomadic Turks settled down to create stable civilizations. Also around 1400, the key military resource became gunpowder weaponry -- both the large cannons that could demolish or defend a walled city or fortress, and the handguns, that trained infantry could use to destroy any force that did not have them. After 1400, throughout the world, in some place more quickly than others, armies were reorganized to take advantage of the new type of weapons. Reorganizing armies meant reorganizing the societies that supported them. Rulers who did that job well were able to put together strong civilizations. Rulers who failed lost control in favor of ones who did a better job of it. Now it is a common assumption that in modern times Western Europe left Islam behind -- Europe successfully modernized and the Islamic countries did not. But as late as 1600, the greatest gunpowder states, whether one is talking about population, area, wealth, or sheer military power, were not European, but Islamic ones: the Ottoman Empire based in Anatolia (later known as Turkey because of the Turkish origin of the Ottomans); the Safavid Empire based in Iran; and the Mughal Empire based in India. Historians of Asia and Islam call these the gunpowder empires. Each of the gunpowder dynasties had Turkish origins, being former nomadic herders from Central Asia, and they all lasted a fairly long time. The Safavid dynasty in Iran, the shortest lived, was founded about 1500, and lasted till 1722. The Mughal dynasty of India began in the 1500s and lasted in name until the 1850s; the champion, the Ottoman dynasty began in the late 1300s, controlled a major empire in the 1400s, and lasted until 1918. Each of the dynasties had fairly stable boundaries and became identified with a particular region. This is clearest in the case of the Safavid empire. Its boundaries are not identical with those of present-day Iran, but they are close enough to fool most of us. Finally, each of the empires had an important impact on the religious composition of society. Let’s start with a brief look at Iran. From the very beginning, the Safavid dynasty was strongly Shia in nature. Shah Ismail made Shia the official religion of Iran, suppressed the Sunni leaders, and set up a Shia religious establishment in each city. His descendants consistently followed that policy, which had two major effects. First, Iran became diplomatically and politically isolated from other Islamic countries, at least much of the time. Shia teachings in Iran stressed that Sunnis were as bad as infidels and maybe worse; Sunni rulers outside of Iran didn’t have a very high opinion of the Safavids, either. Second, the establishment of Shia in Iran eventually undermined the Safavid dynasty, because Shia worshippers did not believe that the Turkish Safavids were the true descendents of Ali. In the end, the skepticism of the Shia religious leadership caused the dynasty to end in 1722. In India during the same period, the Islamic dynasty faced a different situation. By the 1500s, when the Mughals took over, North India and parts of the south had been ruled by Muslims for centuries. Yet the local polytheistic tradition was still thriving. Muslims, though numerous, were a small minority, and Hindu (polytheistic) princes and generals were still an important factor. One of the big questions of imperial politics was how should a Muslim sultan rule such a country. One approach was to find as much common ground with members of the Hindu culture as possible, so that their talents and local connections could be used to the benefit of the ruling dynasty. Rich, influential and powerful families from both traditions intermarried and shared a new culture made up of both Turkish and Hindi elements. From a strict Muslim monotheistic perspective to religious truth, this was clearly a violation of God’s law. Eventually a Mughal emperor was won over to the idea that Islam had to be purified in India, and that the supremacy of Muslims over the rest of the population had to be enforced. This was the Sultan Awrangzeb (1658-1707). He followed his policy with great energy. However, alienating his Hindu people and military was not good politics. The end result was that the Mughal power was undermined. The third and the most important of the gunpowder empires was the Ottoman dynasty. Although it controlled much of the old Middle Eastern homeland of Islam during its existence, and ruled almost all of the Arabic speaking countries, the Ottoman empire was something new. The power of the Ottomans was not based on the old countries of Syria (Phoenicia), Egypt, and Iraq (Mesopotamia). These countries were much less prosperous than they had been in the past. Ottoman power was based on being on the frontier of Islam at a time when the initiative in the wars with Christian Europe passed back to the Muslim side. First, the Ottomans conquered what was left of the Greeks, acquiring a new Christian subject population and a tremendous amount of wealth and power. Second, they replaced their nomadic horsemen with a more professional army trained in the new gunpowder weapons. Borrowing from local tradition, the Ottomans recruited from two sources: slaves imported from the Caucasus region, and their new Greek (and Slavic) Christian subjects. One of the taxes levied on the sultan’s new domains was the devshirme, a tax on children. Young boys in large numbers were conscripted into the sultan’s service. After being converted and educated, they were enrolled in the elite regiments of Janissaries, the most famous slave-recruited army in Islamic history. Like previous slave armies in history like the Mamlukes of Egypt, they were members of the sultan’s personal household, responsible to him alone. They were not allowed to marry until retirement, and their children were not eligible to join their regiments. And they were highly trained soldiers and (after retirement) government officials with a high degree of loyalty to the sultan. The Ottoman rulers also created a two pronged religious policy. After conquering the Greeks, the Ottoman empire found itself master of a tremendous amount of Christian territory. It was not possible to Islamicize this area in a hurry. So the sultans turned the Christian populations over to the rule of their own Greek Orthodox bishops, who were mostly very cooperative with the dynastic authorities. This prevented conflict with Christian believers in the new conquests and gave the sultans reliable deputies over large areas. The same was done for Jews where they lived. The second part of the religious policy applied to the Muslim population. The Ottoman sultans, partly in reaction to the Shia threat from Safavid Iran, were intent on establishing a uniform Sunni religion among their subjects. They did this by controlling the education of religious scholars and keeping important religious positions under their control. In the heyday of the Ottoman Empire, the religious life of the Muslim population -- and of the Christians and Jews -- was under more effective government supervision than ever before in the past. The result of all this was that the prestige of the Ottoman sultans was very great in the Muslim world (except in Iran), and they could claim to be caliphs without fear of contradiction. The Islamic gunpowder empires were among the most impressive political and military powers of the 16th century (1500s). But by the middle of the 18th century (1700s), they were all looking a bit rocky. Christian powers were taking control of territory formerly ruled by Muslims, not just in Europe, but even in India! These Islamic civilizations had all once been vastly superior to Christian Europe in power and technology. Why did they fall so quickly from such an impressive position to one of long-term weakness? Two things come to mind. For much of history, dar-al-Islam (the Empires of Islam) was the center of the world, and represented the center of culture and innovation for the Eastern Hemisphere. But by 1600, it was clear that the major trade routes of the world no longer went through the Middle East. They went through the world’s oceans, which were increasingly under European control. As a result, the advantages of contact with the outside world, access to its resources and new trade opportunities went first to Europe. This had a very bad effect on the economic situation of the Islamic world. Second, the center of innovation in culture was no longer in the Islamic world either. Though Islamic dynasties had latched onto guns even earlier than European dynasties, the other great new machine of the early modern period had almost no effect on Islam. That was the printing press. Perfected in Germany in the 1450s, it was in use throughout Europe by 1500 -- there was even one in the Ottoman city of Constantinople, formerly owned by Greece. But the Constantinople printing press was only used for Christian literature. Islamic religious authorities forbade its use for Islamic texts. Maybe in the short run, the Islamic world avoided a lot of turmoil by rejecting the printing press and its uncontrolled spread of information. In the long run, however, it would pay a high price for choosing to stick only with what it already knew. https://faculty.nipissingu.ca/muhlberger/2805/GUNPOW.HTM