Coker, Heat of Passion - Jewish Women International

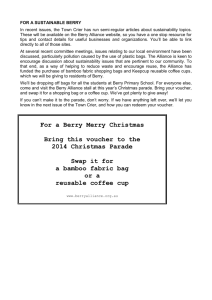

advertisement