Context - Sumeria - renaissanceAPAH

advertisement

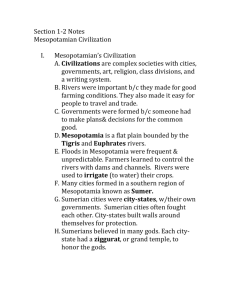

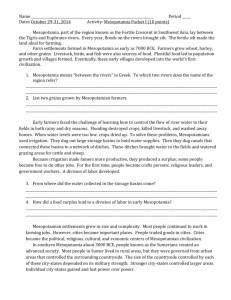

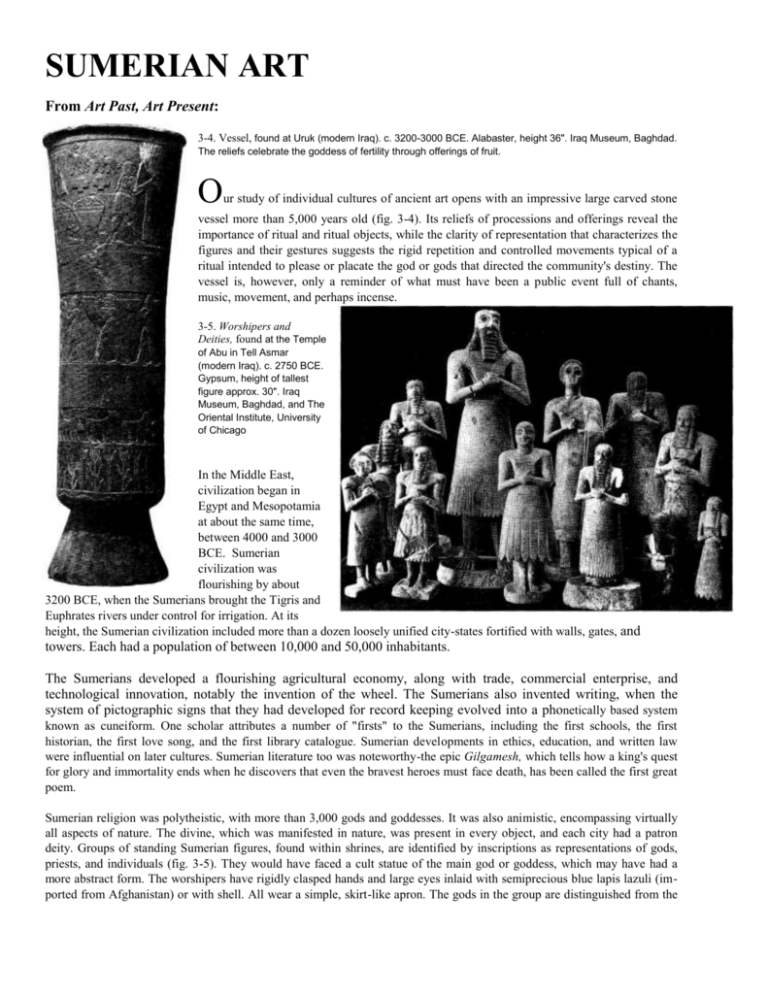

SUMERIAN ART From Art Past, Art Present: 3-4. Vessel, found at Uruk (modern Iraq). c. 3200-3000 BCE. Alabaster, height 36". Iraq Museum, Baghdad. The reliefs celebrate the goddess of fertility through offerings of fruit. O ur study of individual cultures of ancient art opens with an impressive large carved stone vessel more than 5,000 years old (fig. 3-4). Its reliefs of processions and offerings reveal the importance of ritual and ritual objects, while the clarity of representation that characterizes the figures and their gestures suggests the rigid repetition and controlled movements typical of a ritual intended to please or placate the god or gods that directed the community's destiny. The vessel is, however, only a reminder of what must have been a public event full of chants, music, movement, and perhaps incense. 3-5. Worshipers and Deities, found at the Temple of Abu in Tell Asmar (modern Iraq). c. 2750 BCE. Gypsum, height of tallest figure approx. 30". Iraq Museum, Baghdad, and The Oriental Institute, University of Chicago In the Middle East, civilization began in Egypt and Mesopotamia at about the same time, between 4000 and 3000 BCE. Sumerian civilization was flourishing by about 3200 BCE, when the Sumerians brought the Tigris and Euphrates rivers under control for irrigation. At its height, the Sumerian civilization included more than a dozen loosely unified city-states fortified with walls, gates, and towers. Each had a population of between 10,000 and 50,000 inhabitants. The Sumerians developed a flourishing agricultural economy, along with trade, commercial enterprise, and technological innovation, notably the invention of the wheel. The Sumerians also invented writing, when the system of pictographic signs that they had developed for record keeping evolved into a phonetically based system known as cuneiform. One scholar attributes a number of "firsts" to the Sumerians, including the first schools, the first historian, the first love song, and the first library catalogue. Sumerian developments in ethics, education, and written law were influential on later cultures. Sumerian literature too was noteworthy-the epic Gilgamesh, which tells how a king's quest for glory and immortality ends when he discovers that even the bravest heroes must face death, has been called the first great poem. Sumerian religion was polytheistic, with more than 3,000 gods and goddesses. It was also animistic, encompassing virtually all aspects of nature. The divine, which was manifested in nature, was present in every object, and each city had a patron deity. Groups of standing Sumerian figures, found within shrines, are identified by inscriptions as representations of gods, priests, and individuals (fig. 3-5). They would have faced a cult statue of the main god or goddess, which may have had a more abstract form. The worshipers have rigidly clasped hands and large eyes inlaid with semiprecious blue lapis lazuli (imported from Afghanistan) or with shell. All wear a simple, skirt-like apron. The gods in the group are distinguished from the individuals by hierarchical scale (they are larger) and their enormous eyes. The statuettes of individuals would have served to present the life spirit of the donor in an attitude of continuous and vigilant prayer-a permanent and ever-alert substitute for the donor, who may not have been allowed to enter the sacred shrine. 3-7. Ziggurat, Ur (modern Iraq). c. 2100 BCE. Fired brick over mud-brick core, original height approx. 70', base 210 x 150'. Commissioned by several Sumerian rulers, including Ur-Nammu The most impressive structure of a Sumerian city-and of ancient Middle Eastern cities in general was the ziggurat (from the Akkadian "pinnacle" or "mountaintop"), a high, terraced structure. The fifth century BCE Greek historian Herodotus gave us a verbal picture of a ziggurat when he described the "Tower of Babel": it was 300 feet tall with, at its apex, a temple with a large couch and table of gold to be used by the god when he came down to earth. The best-preserved ziggurat is at Ur (fig. 37), the city thought to be the childhood home of the Old Testament figure Abraham. The structure was built on the ruins of earlier ziggurats by several Sumerian kings, including Ur-Nammu, who wrote one of the earliest codes of law. It had a temple at the base and another, built entirely of blue enameled bricks, crowning the summit. This ziggurat's main deity was Ur's patron, the moon god, Nanna-Sin. At the New Year festival, processions ascended the three staircases and proceeded through a ceremonial gateway to a brilliantly decorated temple with a cult statue and sacrificial altar at the top. The Sumerian mother goddess was Ninhursag, the "Woman of the Mountain," and the mountains were the source of the water that nourished their country. As human-made sacred mountains, ziggurats enabled rulers and priests to ascend, during rituals, to the residence of the gods to ask for divine guidance in political and religious affairs. An early Mesopotamian text refers to a ziggurat as the "bond between heaven and earth." From Gardner’s Art Through the Ages, 10th edition Sometime in the early fourth millennium B.C. a critical event--the settlement of the great river valleys-took place in Mesopotamia (a Greek word meaning "the land between the [Tigris and Euphrates] rivers"). Writing, monumental architecture, and new political forms appeared shortly thereafter, both in Mesopotamia and in Egypt. From this time forward, world history was to be the record of the birth, development, and disappearance of civilizations and the rise and decline within them of peoples, states, and nations. It is with the emergence of the two mighty, contrasting civilizations of Mesopotamia and Egypt that the drama of Western humanity truly begins. One must not think, however, that these two distinct societies were geographically or culturally isolated from each other. Ancient Palestine and Syria connected them on the west. On the east, Mesopotamia adjoined the vast territory of Iran and the north Indian civilization of the Indus River valley, with its important city of Mohenjo-Daro (see Chapter 14). Thus, a continuous range of more or less contemporaneous city civilizations existed from Egypt to India, linked by trade, cultural diffusion, and conquest, and ringed by nomadic peoples or sedentary farmer villages in Arabia, North Africa, and northern Eurasia. SUMERIAN ART At the dawn of recorded history, the fertile lower valley of the Tigris and Euphrates was occupied by the Sumerians, an agricultural people who utilized both the wheel and the plow and learned to control floods and construct irrigation canals to divert the river channels and bring fertility to the lands not immediately adjacent to the two great waterways. In fact, the Sumerians transformed this vast, flat, and formerly sparsely inhabited land into a veritable oasis, often referred to as the "fertile crescent" of the ancient world. Within this crescent, thought to be the site of the biblical Garden of Eden, the Sumerians established the first great urban communities, among them Uruk (Erech in the old Testament, modern Warka) and Lagash (Al-Hiba), and they developed the earliest known script, which in time became the system of wedge-shaped (cuneiform) signs that was regularly used for recording administrative acts and commercial transactions. The Sumerians also produced a significant literature, most notably the Epic of Gilgamesh, which antedates Homer's Iliad and Odyssey by some fifteen hundred years. The origin of the Sumerians is still uncertain and their language does not belong to any of the major linguistic groups of antiquity, but there is no doubt that the Sumerians were a major force in the spread of civilization. Their influence extended widely from southern Mesopotamia, eastward to the Iranian plateau, northward to Assur, and westward to Syria, where archeologists have discovered archives, consisting of thousands of day tablets, some in the Sumerian language, testifying to the far-flung network of Sumerian contacts made throughout the ancient Near East. Trade was essential for the Sumerians, because, despite the fertility of their land, it was poor in such vital natural resources as metal, stone, and wood. From as early a time as the Paleolithic caves, we have evidence of people's efforts to control their environment by picture magic. With the appearance of the Sumerians and the beginning of recorded history, the older magic was replaced by a religion of gods and goddesses, benevolent or malevolent, who personified the forces of nature that often contended destructively with human hopes and designs. While the waters of the Tigris and Euphrates made possible the cultivation of the land and the formation of the first true urban centers in human history, the climate of ancient Mesopotamia also produced the fiery heat of summer and the catastrophic floods, droughts, blights, and locusts that might easily have persuaded people that powers above and beyond their control must somehow be placated and won over. Formal religion, a kind of system of transactions between gods and human beings, may have begun with the Sumerians; no matter how it has been systematized and diversified since then, religion has retained its original propitiatory devices--prayer, sacrifice, and ritual--as well as a view of humans as imperfect by nature and dependent on and obligated to some higher being. The religion of the Sumerians and those who followed them centered about nature gods, among them Anu, god of the sky and supreme deity in the Mesopotamian pantheon; En-lil, lord of the winds and of the earth; Abu, god of vegetation; Ea (or Enki), ruler of the waters; Nanna (Sin), the moon god; and Utu (Shamash), the sun god. Ancient Sumer was not a unified nation but was made up of a dozen or so independent city-states, each of which was thought to be under the protection of one of the Mesopotamian nature gods. The Sumerian rulers were the god's representatives on earth and the stewards of the god's earthly treasure. The priests were the chief civic administrators, who directed all communal activities, such as the construction of canals and the collection and distribution of food to those who were not farmers themselves. This specialization of labor--made possible by the development of agriculture to the point where only a portion of the population had to be engaged in food production, freeing others to take up activities such as manufacturing, trade, and administration--is the hallmark of the first complex urban societies. It was in the city-states of ancient Sumer that activities that once had been left to the individual became regularized, with the community assuming functions such as defense against others and the caprices of nature. The city-state itself, with its permanent identity as a discrete community ruled by a single person and a god with specific names, was one of the great inventions of the Sumerians, along with the art of writing and the system of gods and god-human relationships. Together these innovations provided the basis for a new order of human society. Architecture The plan of the Sumerian city reflected the central role of the god in city life, the god's temple being the city's monumental nucleus. The temple was not only the focus of local religious practice but also served as an administrative and economic center. It was indeed the domain of the god, who was regarded as a great and rich holder of lands and herds as well as the protector of the city. The vast temple complex, a kind of city within a city, had multiple functions. A temple staff of priests and scribes carried on city business, looking after the possessions of the god and of the ruler. It must have been in such a setting that writing developed into an instrument of precision; the very earliest examples have to do with the keeping of accounts. The priests recorded transactions and inventories by pressing a stylus into wet clay plaques; these hardened into breakable, yet nearly indestructible, tablets. Hundreds of thousands of these tablets have survived to this day and give us insights into the nature of life in these first cities, information that we will never have for the era before the invention of writing. The outstanding preserved example of early Sumerian temple architecture is the so-called White Temple (FIG. 2-1) at Uruk (the home of the legendary Gilgamesh), which dates to the late fourth millennium B.C. Usually only the foundations of early Mesopotamian temples can still be recognized; the White Temple is a rare exception. Sumerian builders did not have access to stone quarries and instead utilized mud brick for the superstructures of their temples and other buildings, which have almost all eroded over the course of time. The fragile nature of the building materials did not, however, prevent the Sumerians from erecting towering structures like the Uruk temple several centuries before the stone pyramids of the Egyptians. This says a great deal about the desire on the part of the Sumerians to provide monumental settings for the worship of their deities. AKKADIAN ART The godlike sovereignty claimed by the kings of Akkad is also evident in another masterpiece of Akkadian art, the victory stele (FIG. 2-13) set up by Naram-Sin at Sippar to commemorate his defeat of the Lullubi, a people of the Iranian mountains to the east. The stele is inscribed twice, once in honor of Naram-Sin, and once by a twelfth century B.C. Elamite king who had captured Sippar and taken the stele as booty back to Susa, where it was found. 2-13 Victory stele of Naram-Sin, from Susa, c. 2200 B.C. Pink sandstone, approx. 6' 7" high. Louvre, Paris. NEO-SUMERIAN ART The achievements of Akkad were brought to an end by an incursion of barbarous mountaineers, the Guti, who dominated life in central and lower Mesopotamia until the cities of Sumer, responding to the alien presence, reasserted themselves and established a Neo-Sumerian polity under the kings of Ur. This is the age that saw the construction of the great ziggurat at Ur (FIG. 2-4), but the most conspicuous sculptural monuments come from the city of Lagash, under its governor, Gudea. There are about twenty preserved statues of Gudea, showing him seated or standing, hands tightly clasped, sometimes wearing a woolen brimmed hat and always dressed in a long garment that leaves one shoulder and arm exposed; the statue illustrated here (FIG. 2-14) is typical. Gudea attributed his good fortune and that of his city to the favor of the gods, and he was a zealous overseer of the performance of rites in their honor. His statues were numerous so that he could take his symbolic place in the temples and there render perpetual service to the benevolent deities--as the cuneiform inscription on the lap of our statue explicitly states. BABYLONIAN ART Lagash, which had retained its independence during the Guti invasion, became a dependency of Ur during that city's brief resurgence late in the third millennium B.C. For a little over a century, the Third Dynasty of Ur ruled a once more united realm. Its last king fell before the attacks of foreign invaders, and the following two centuries witnessed the re-emergence of the traditional Mesopotamian political pattern in which several independent citystates existed side by side. Until its most powerful king, Hammurabi, was able to re-establish a centralized government that ruled the whole country, Babylon was one of these city-states. Perhaps the most renowned king in Mesopotamian history, Hammurabi was famous for his law code, which prescribed penalties for everything from adultery and murder to the cutting down of a neighbor's trees. ASSYRIAN ART For most of the first half of the first millennium B.C., the Assyrians (who take their name from Assur, the city on the Tigris River in northeastern Syria named for the god Assur) were the dominant power in the Near Eastern world, having overcome all the warring peoples that succeeded the Babylonians and Hittites, among them the Kassites and the Mitanni. By about 900 B.C. the Assyrian Empire was firmly established. Assyria, with its center successively at Nimrud, Khorsabad (ancient Dur Sharrukin), and Nineveh, was a garrison state with an imperial structure that extended from the Tigris to the Nile and from the Persian Gulf to Asia Minor. Centuries of unremitting warfare against their neighbors and often rebellious subjects hardened the Assyrians into a cruel and merciless people whose atrocities in warfare were bitterly decried throughout the ancient world. Architecture The unfinished royal citadel of Sargon II of Assyria built at Khorsabad reveals in its ambitious layout the confidence of the Assyrian kings in their all-conquering might--but, with its strong defensive walls, it also reflects a society ever fearful of attack during a period of almost incessant warfare. The palace covered some 25 acres and had over two hundred courtyards and rooms. The city itself, above which the citadel-palace stood on a mound 50 feet high, measures about a square mile in area. The palace may have been elevated solely to raise it above flood level, but its elevation served also to put the king's residence above those of his subjects and midway between his subjects and the gods. 2-18 Reconstruction drawing of the citadel of Sargon II, Khorsabad. c. 720 B.C. (After Charles Altman.) Sargon II regarded his city and palace as an expression of his grandeur, which he viewed as founded on the submission and enslavement of his enemies. He writes in an inscription: "I built a city with [the labors of] the peoples subdued by my hand, whom Assur, Nabu, and Marduk had caused to lay themselves at my feet and bear my yoke at the foot of Mount Musri, above Nineveh." And in another text, he proclaims: "Sargon, King of the World, has built a city. Dur Sharrukin he has named it. A peerless palace he has built within it." The Assyrian kings expected their greatness to be recorded in unmistakably exact and concrete forms in their palaces, and in the official quarter of their citadels the lower parts of the thick mud-brick walls were revetted with limestone slabs (which were more readily available in northern than in southern Mesopotamia) and carved with relief sculptures exalting the king, his victories on the battlefield, and his triumphs over powerful beasts. Prowess in hunting was widely regarded as a manly virtue on a par with success in warfare. The history of Assyrian art is mainly the history of relief carving; very little sculpture in the round survives. Even the great lamassu, conceived as relief sculptures, are, as we have seen, locked into their stone slabs. The narrative reliefs of warfare and hunting that covered the walls of the Assyrian palaces are among the first monumental historical chronicles in stone that we possess. Not until the rise of the Roman Empire will we again see historical events regularly recorded for posterity in relief sculpture. NEO-BABYLONIAN ART The Assyrian Empire was never very secure, and most of its kings had to fight revolts in large sections of the Near East. Opposition to Assyrian rule increased steadily throughout the seventh century B.C., and during the last years of Ashurbanipal's reign, the empire began to disintegrate. Under his weak successors, it collapsed before the simultaneous onslaught of the Medes from the east and the resurgent Babylonians from the south. Babylon rose once again, and in a brief renewal (612-538 B.C.), the old southern Mesopotamian culture flourished. King Nebuchadnezzar, whose exploits are recounted in the biblical Book of Daniel, restored Babylon to the rank of one of the great cities of antiquity, and its famous "hanging gardens" were counted among the seven wonders of the ancient world. Only a little of the great ziggurat of Babylon's temple to Bel (the Hebrews' Tower of Babel) remains, but the fifth-century B.C. Greek historian Herodotus, in his chronicle of the war between the Greeks and the Persians, has left us the following description of the temple complex: In the one [division of the city] stood the palace of the kings, surrounded by a wall of great strength and size; in the other was the sacred precinct of Zeus-Bel, an enclosure a quarter of a mile square, with gates of solid brass, which was also remaining in my time. In the middle of the precinct, there was a tower of solid masonry, a furlong in length and breadth, on which was raised a second tower, and on that a third, and so on up to eight. The ascent to the top is on the outside, by a path which winds round all the towers. When one is about halfway up, one finds a resting place and seats, where persons are wont to sit some time on their way to the summit. On the topmost tower, there is a spacious temple, and inside the temple, stands a couch of unusual size, richly adorned, with a golden table by its side. . . . They also declare that the god comes down in person into this chamber, and sleeps on the couch, but I do not believe it. ACHAEMENID PERSIAN ART Although Nebuchadnezzar, Daniel's "King of Kings," had boasted that "I caused a mighty wall to circumscribe Babylon. . . so that the enemy who would do evil would not threaten. . . [and] of the city of Babylon [I] made a fortress," his city was taken in the sixth century B.C. by Cyrus of Persia (559-529 B.C.). Cyrus, who may have been descended from an Elamite line, was the founder of the Achaemenid dynasty and traced his ancestry back to a mythical King Achaemenes. The impetus of the Persians' expansion carried them far beyond Babylon. Egypt fell to them in 525 B.C., and by 480 B.C., the Persian Empire was the largest the world had ever known, extending from the Indus to the Danube; only the successful resistance of the Greeks in the fifth century prevented it from embracing southeastern Europe as well. The Achaemenid line came 10 an end with the death of Darius III in 330 B.C., after his defeat in the Battle of Issus (see FIG. 5-79) and the fall of his empire to Alexander the Great. Architecture The most important source of our knowledge of Persian architecture is the palace at Persepolis (FIG. 2-25), built between 520 and 460 B.C. by Darius I and Xerxes I, successors of Cyrus. Situated on a high plateau, the heavily fortified palace stood on a wide platform overlooking the plain. Although destroyed by Alexander the Great in a gesture symbolizing the destruction of Persian imperial power (and. some say, as an act of revenge for the Persian sack of the Athenian acropolis in the early fifth century B.C.), the still impressive ruins of the palace complex permit a fairly complete reconstruction of its original appearance, ambitious scale, and spatial intricacy. Persian conquests, of course, brought to Cyrus and his successors not merely new artistic ideas, but also great wealth. Numerous surviving items of fine tableware in precious metals attest to the excellence of the goldsmiths and silversmiths in the employ of the Persian nobility. SASANIAN ART With the conquest of Persia by Alexander the Great in 330 B.C., the history of the ancient Near East becomes part of the history of Greece and Rome. In the third century A.D., however, a new power rose up in Persia to challenge the Romans and sought to force them out of Asia. The new dynasts called themselves Sasanians and traced their lineage to a legendary figure named Sasan, who was said to be a direct descendant of the Achaemenid kings. Their New Persian Empire was founded in A.D. 224, when the first Sasanian king, Artaxerxes I (211-241), defeated the Parthians (another of Rome's eastern enemies) and established his capital at Ctesiphon, near modern Baghdad in Iraq. The son and successor of Artaxerxes, Shapur I (241-272), succeeded in further extending Sasanian territory and even captured the Roman emperor Valerian (near Edessa in modern Turkey) in 260. Shapur's palace at Ctesiphon is today in a ruined state… Both the pointed arch and the blind arcades will prove to be enduring features of Islamic architecture, both in the Near East and elsewhere… The great victory of Shapur lover Valerian was commemorated in a series of rock-cut reliefs in the cliffs of Bishapur.