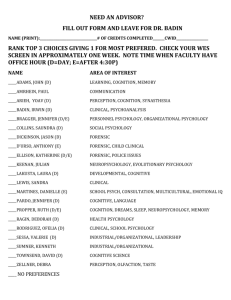

Forensic Psychology - Gwinnett County Public Schools

advertisement

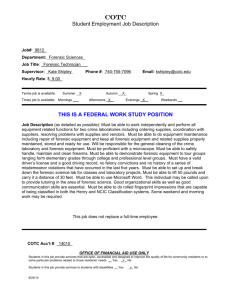

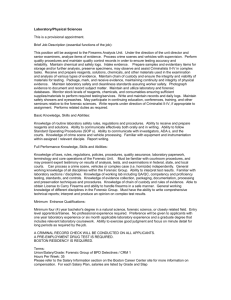

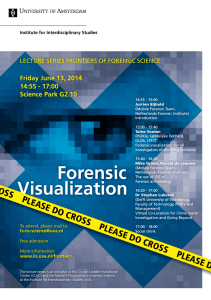

Forensic Psychology Adapted from: http://www.wcupa.edu/_ACADEMICS/sch_cas.psy/Career_Paths/Forensic/Career 08.htm FORENSIC PSYCHOLOGY is the application of psychology to the criminal justice system. Many people confuse Forensic Psychology with forensic science. Although the two are closely related, there are many differences. The primary difference is that forensic psychologists dive into the vast psychological perspectives and apply them to criminal justice system. On the other hand, forensic psychologists frequently deal with legal issues, such as public policies, new laws, competency, and also whether a defendant was insane at the time a crime occurred. All of these issues weave together psychology and law topics and are essential to the discipline of Forensic Psychology. Forensic Psychology knowledge is used in various forms, such as in treating mentally ill offenders, consulting with attorneys (e.g., on picking a jury), analyzing a criminal's mind and intent, and practicing within the civil arena. Individuals interested in pursuing a Forensic Psychology career would have take psychology and criminal justice courses in their academic studies. There is a very limited number of academic institutions that specifically offer a Forensic Psychology degree. A forensic psychologist may chose to solely focus his/her career on research, ranging anywhere from examination of eyewitness testimony to learning how to improve interrogation methods. Another form of Forensic Psychology work is public policy, in which researchers can help in the design of correctional facilities and prisons. A Brief History Forensic Psychology dates back to at least the turn of the twentieth century. William Stern studied memory in 1901 by asking students to examine a picture for forty-five seconds and then try to recall what was happening in it. He would see how much the person could recall at various intervals after seeing the picture. These experiments came before more contemporary research about the reliability of eyewitnesses testimony in court. Stern concluded from his research that recall memories are generally inaccurate; the more time between seeing the picture and being asked to recall it, the more errors were made. People especially recalled false information when the experimenter gave them a lead-in question such as, "Did you see the man with the knife?" The person would answer, "yes," even if there was no knife present. Lead-in questions are often used in police interrogations and in questioning witnesses. Important Terms and Definitions The following are terms that are important to be familar with when learning about Forensic Psychology: Some Important Terms in Forensic Psychology Competency The mental condition of the defendant at the time of trial is brought up every now and then by the defendant. If a defendant is found to be incompetent, our justice system will not usually punish him/her. Insanity Sometimes forensic psychologists are asked to determine whether a defendant was mentally capable at the time an offense was committed, commonly by employing the McNaughton rule and/or the substantial capacity rule. Expert Witness The majority of forensic psychologists testify in court for both the defense and also for prosecuting attorneys about the sanity and competency of defendants, the accuracy of the eye witness, in child custody cases, and also a variety of other things. Criminal Profiling With a lot of experience and schooling, one could work closely with local police and also federal agencies to create psychological profiles of defendants. Jury Consulting Many forensic psychologists work with attorneys in selecting jurors, analyzing the A Typical Day Practicing Forensic Psychology The typical day of a forensic psychologist can vary. In general, it is oriented toward research activities. However, a psychologist may do other things as well, such as helping with jury selection. In this case, the psychologist would wake up fairly early and gather information on studies done on juries especially relevant to a pending case. They would then go to a courthouse or to an attorney's office to sift through papers or conduct interviews of possible jurors. The psychologist might also help attorneys narrow down the juror pool by eliminating people whose views may affect the outcome of the trial in an undesirable way. This process can sometimes last several weeks or even longer.