Tuesday 7 October 2014

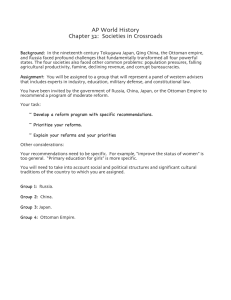

advertisement