a theory of self and personal relationships

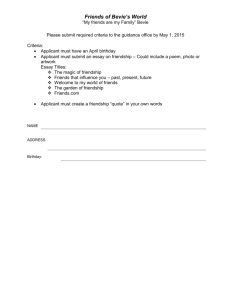

advertisement