The time famine: Toward a sociology of work time

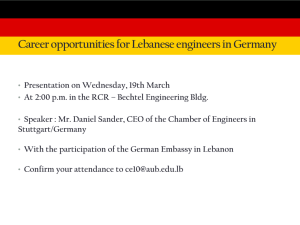

advertisement