Let's get real: Working With Service Users learning module

advertisement

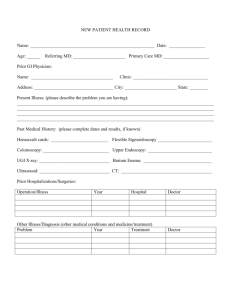

Working with service users Practitioner level learning module Published in September 2009 by Te Pou o Te Whakaaro Nui The National Centre of Mental Health Research, Information and Workforce Development. PO Box 108-244, Symonds Street, Auckland, New Zealand. ISBN 978-1-877537-30-1 2 Web www.tepou.co.nz/letsgetreal Email letsgetreal@tepou.co.nz Working with Service users – Practitioner level Learning module – electronic version Contents Introduction ....................................................................................................................4 1 Recovery ..................................................................................................................7 2 Recovery in practice – practising recovery ....................................................................... 12 3 Therapeutic relationships and partnership ....................................................................... 17 4 Partnership tools ...................................................................................................... 20 5 Practice knowledge ................................................................................................... 24 References and recommended reading .................................................................................. 30 Learning Review Tool ....................................................................................................... 33 Individual Professional Development Plan .............................................................................. 35 3 Introduction The Real Skill for working with service users is: Every person working in a mental health and addiction treatment service utilises strategies to engage meaningfully and work in partnership with service users, and focuses on service users’ strengths to support recovery. Some people have experienced recovery without using mental health services. Others have experienced recovery in spite of them. But most will do much better if services are designed and delivered to facilitate their recovery. Virtually everything the mental health sector does can either assist or impede recovery (Mental Health Commission, 1998). Performance indicators - practitioner By the end of this module you will be able to: develop effective therapeutic relationships with service users and work flexibly with them apply understanding of the different stages of life development recognise the varying social, cultural, psychological, spiritual and biological contributors to mental illness and addiction connect with tāngata whaiora and their family/whānau with cultural support and expertise when appropriate, for example, te reo, karakia, kaumātua, kaupapa Māori services and practitioners apply, in your day-to-day work, in-depth knowledge or understanding of: definitions and categories of mental illness and addiction assessment and intervention processes, including but not limited to consideration of risk psychiatric pharmacology and its effects the range of evidence-informed therapies and interventions available the impact of physical health on mental health practise the principles of trauma-informed care actively work in partnership with service users to plan for their recovery, including monitoring and review. Preparation To help you complete this module, please familiarise yourself with key national strategy and policy documents and the service provider guidelines relevant to your specific area of practice. It is also recommended that you do some background reading of recent research and publications related to working with service users. For your reference a list of recommended reading is included in this module. The following New Zealand publications will provide you with an overview. 4 Recovery Competencies for New Zealand Mental Health Workers (Mental Health Commission, 2001). The purpose of this document is to provide educators with guidance on including recovery content in Working with Service users – Practitioner level Learning module – electronic version the courses they run. It outlines recovery-based competencies and includes extensive lists of national and international resources to support these. Our Lives in 2014: A recovery vision from people with experience of mental illness (Mental Health Commission, 2004). The purpose of this document is to guide development of the Ministry of Health’s second mental health plan, and to influence the overall development of the services and sectors that affect people with mental illness. I Haven’t Told Them, They Haven’t Asked (Peterson, 2007). This publication details specific issues that affect people with experience of mental illness in employment. “Kia Mauri Tau!”: Narratives of recovery from disabling mental health problems (Lapsley et. al, 2002). This report follows the stories of 40 people who have suffered from disabling mental illness. Culture, personal and stigma issues are discussed in relation to recovery. The work in this module builds on the essential level of the working with service users Real Skill. It is designed to capture your knowledge and its application in your particular area in mental health and addiction. You will be expected to reflect on what you do, how you do it, and the key values and attitudes that underpin your work. There are four main themes in this module: recovery and how it is used within your service recovery in practice and working in holistic ways therapeutic relationships and working in partnership the knowledge you use on a day-to-day basis. You will draw on your experiences working with service users, along with the strategies and plans that are implemented to support their recovery. It is suggested that, before beginning this module, you consider service users you have worked with in the past or are currently work with, the different types of challenges they have faced, the strategies that have been used to overcome those challenges, and their journey of recovery. To gain the maximum benefit from this module you are encouraged to think about how the learning module applies to you and your work context. There are two learning reviews in this module. The first assesses your knowledge of the recovery competencies (page 7). The second is found at the end of this module and is a Learning Review Tool to help you reflect on how you work with service users. This will enable you to identify where your strengths are, along with any areas you may need to further explore in your Individual Professional Development Plan. Overview Recovery has become the fundamental paradigm in New Zealand mental health policy and practice. Although variously described, the recovery approach in both mental health and addiction places emphasis on the need to draw on the resources of all people with and affected by mental illness and addiction (Mental Health Commission, 2001; Mental Health Advocacy Coalition, 2008). Recovery happens when people with mental illness take an active role in improving their lives, when communities include people with mental illness, and when mental health services can enable people with 5 mental illness and their communities and families to interact with each other (Mental Health Commission, 2001, p.2). The process of recovery from problematic substance use is characterised by voluntarily-sustained control over substance use, which maximises health and well-being and participation in the rights roles and responsibilities of society (UK Drug Policy Commission Recovery Consensus Group, 2008, p. 6). In Recovery, as a Journey of the Heart (Deegan, 1995) Patricia Deegan gives a clear illustration of the role of the service user within that journey. … Like a pebble tossed into the centre of a still pool, this simple fact [of having a mental illness] radiates in ever larger ripples until every corner of academic and applied mental health science and clinical practice are affected. Those of us who have been diagnosed are not objects to be acted upon… We are human beings and we can speak for ourselves… We can become experts in our own journey of recovery. The goal of the recovery process is not to become normal. The goal is to embrace our human vocation of becoming more deeply, more fully human. The goal is not normalisation. The goal is to become the unique, awesome, never to be repeated human being that we are called to be… To be human means to be a question in search of an answer. However, many of us who have been psychiatrically labelled have received powerful messages from professionals who in effect tell us that by virtue of our diagnosis the question of our being has already been answered and our futures are already sealed (p. 3). Recovery in mental health service delivery and policy Recovery is seen in service delivery and policy documents as a goal that will only be achieved by working collaboratively and in partnership with service users. In New Zealand, the focus on recovery has influenced a number of important developments and has impacted on the quality; monitoring and consequent changes in the way mental health and addiction services are delivered. However, it is the following statement from Te Tāhuhu: Improving mental health 2005–2015 (Ministry of Health, 2005) that highlights the need for services to work more collaboratively and in inclusive ways: …recognition that social and economic factors such as employment, housing, and poverty all impact on mental health, well-being and recovery – and an understanding of how essential it is that all parts of the State Sector and wider community services, work together to provide services (p. 2). 6 Working with Service users – Practitioner level Learning module – electronic version 1 Recovery The activities in this module build on the essential level of the working with service users Real Skill. The overarching theme in this module is recovery. Recovery, as it applies to the Real Skills, refers to the way you work to support the autonomous choices and decisions made by service users so that they may “live well in the presence or absence of… mental illness” (Mental Health Commission, 1998, p. 1). Mental health and addiction practitioners should acknowledge that every person and their experience of mental illness is different, and that therefore defining living well is both personal and unique to each individual. Unlike specific models of service delivery, recovery is an approach that can be “applied to any model that draws on the resources of service users and their communities” (Mental Health Commission, 2001, p. 1). 1.1 Reflect on the Recovery Competencies for New Zealand Mental Health Workers (Mental Health Commission, 2001). Then, on the scales below, indicate where you see your understanding of each recovery competency. Where you have identified gaps in your knowledge, refer to the recovery competencies for a list of helpful resources. I understand recovery in the New Zealand and international contexts. 1 2 3 4 Very little understanding 5 Full understanding I recognise personal resourcefulness, and can help identify and support the strengths of people with mental illness. 1 2 3 4 Could learn more 5 Very confident I understand and can accommodate diverse views on mental illness, treatments, services and recovery. 1 2 3 4 Very little understanding 5 Full understanding I use self-awareness and skills to communicate respectfully and develop good relationships with service users. 1 Could develop further 2 3 4 5 Very confident 7 I understand and work to protects service users’ rights. 1 2 3 4 Very little understanding 5 Full understanding I understand discrimination and social exclusion, its impact on service users and how to reduce it. 1 2 3 4 Very little understanding 5 Full understanding I acknowledge the different cultures of New Zealand and know how to provide a service in partnership with them. 1 2 3 4 Could learn more 5 Very confident I have a comprehensive knowledge of community services and resources, and actively support service users to use them. 1 2 3 4 Could learn more 5 Very confident I have knowledge of the ‘Consumer Movement’ and know how to support service user participation in it. 1 2 3 4 Very little understanding 5 Full understanding I have knowledge of family and whānau perspectives, and how to support family and whānau participation in services. 1 2 3 Could learn more 8 Working with Service users – Practitioner level Learning module – electronic version 4 5 Very confident 1.2 In considering your role in supporting service users in their recovery, a valuable resource is Our Lives in 2014: A recovery vision from people with experience of mental illness (Mental Health Commission, 2004). This publication was written by service users with the purpose of guiding the development of the Ministry of Health’s second mental health plan Te Tāhuhu (Ministry of Health, 2005). It emphasises that service users seek the right to personal power, a valued place within families, whānau and communities, and services to support them to lead their own lives. Consider your own life and your access to different opportunities. Reflect on the supportive aspects of belonging to clubs, sports teams, church groups or spiritual networks, undertaking study within educational institutes, being provided with adequate support to gain qualifications, or having the ability to apply for or resign from a variety of different employment opportunities. The following diagram outlines seven key areas of life in which you have the opportunity of participating. Consider how you would feel if that opportunity were denied to you. If you were denied access to your family, how would you feel? If you were excluded from a group, club or organisation, what would you do? Or if you were turned down for a job with no reason given, how would you cope? In your experience, how do you make service users aware of the opportunities represented in the diagram above? 9 1.3 Reflect on a service user or service users you have worked with. Give at least two social and two cultural networks the person or persons accessed, and how belonging to these networks may have supported their recovery. 1.4 A vision is a dream or potential goal. Vision statements commonly represent a variety of perspectives, including those of key stakeholders, management, services users and practitioners. In the essential module for working with service users, you were asked to complete activities that related to vision or mission statements. You may want to revisit these activities, or find and consider the vision or mission statement of your organisation. Reflect on the vision or mission statement of your organisation. In your opinion, explain whose perspectives it represents. 10 Working with Service users – Practitioner level Learning module – electronic version 1.5 Thinking about recovery and how it applies to the work you do, give an example how the vision statement of your organisation meets each of the following. Enhancing the autonomy of service users For example: In our service, the service user leads the process of recovery planning. My specific role in recovery planning is supporting the decisions or the choices the service users makes, and includes providing education and information on how they can attain their own aspirations and goals. Valuing the participation of service users in their whānau Valuing the participation of service users in their communities Supporting service users to have, and to use, personal power 1.6 Translating the vision statement into action is fundamental to your role. Provide two examples to show how your work aligns to the vision statement. 11 2 Recovery in practice – practising recovery Recovery happens when people with mental illness take an active role in improving their lives, when communities include and involve people with mental illness, and when mental health services can enable people with mental illness and their communities and families to interact with each other. One practical example of adopting a recovery approach is to work from a strengths-base perspective. Strengths-based practice is consistent with recovery in mental illness and addiction as it focuses on the service user, and their abilities, interests and capabilities, as well as their strengths and potential. Working from a strengths-based perspective requires that practitioners are committed to the idea of growth, and that service users can effect positive change for themselves. Strengths-based practice also places the service user and their family and whānau as the primary partner in relationships. Service users hold the expert position on developing their own goals and recovery plans, and are active rather than passive participants in their own recovery. 2.1 In what way does the model or approach that you use in your work setting reflect the principles of recovery, including participation, self-determination, choice and hope? In exploring your own understanding of recovery, consider each of the stories described below. To help you complete the activities that follow, locate any forms or documents that you have completed to help people plan for their recovery. Reflect on the information you provided, any challenges you may have faced when filling out the forms, and the strategies you used to meet those challenges. Paul’s story My name is Paul. I am 67 years old and have been in and out of mental health services for the better part of 45 years. I try to think about my life before getting sick but it’s hard. I have been on a concoction of medications and the doses of lithium, clonazepam and sleeping pills have varied over the years. My memory isn’t what it used to be. I do remember my dad though. His large hands covered in oil and his terrible temper. I remember my mum, she was such a great cook, but for some reason she was always crying, then things become hazy. Outside of institutions I don’t remember much else. I love carving, making wooden animals and toys, which I give to the Salvation Army shop in the local mall. I am also a keen gardener and keep a variety of potted vegetable and fruit plants in the conservatory area in my flat. I have grown different types of egg plant and differently coloured tomatoes. I can’t eat all the vegetables or the fruit I grow, so instead I leave them in a box on my doorstep for the other tenants in the complex. They thank me for this. I am not too good at talking to strangers. My support worker is great, but I keep forgetting her name. I have been working with her for a couple of months now. It might actually be six months but I tend to lose track of time. She comes in and helps me find things that someone keeps moving. The other week I had an accident in my flat and she was the one who found me. They were going to move me out of my flat after that and into a complex that catered for the elderly. I can’t remember when I got old but I do know that I don’t want to move. 12 Working with Service users – Practitioner level Learning module – electronic version 2.2 What age specific strategies are needed to support Paul? Give at least two examples and an explanation for each. 2.3 Paul does not want to move from the complex in which he currently lives. How would you support him in this decision? Include reference to networks and access to information that would support your strategy. 2.4 Paul is finding the discussions about being moved out of the complex extremely distressing. He has said he ‘knows everyone on the complex, even if I don’t talk to them. I know where everything is in my flat and I don’t want a new support worker. I am feeling really worried about this situation’. If there were no other option but to move Paul to a complex where he would be offered more appropriate support, what would you do to ensure this was done without causing Paul further distress or trauma? 2.5 Paul was moved to a complex for elderly people. You meet him four weeks after his move and he seems happy enough. But when you review his recovery plan, one of his goals was to start a new garden. Since moving, this has not happened. How would you support him in beginning this? 13 Hyun Joo’s story My father is a Korean war veteran and an electroshock therapy survivor from hospitalisation in the 40s and 50s. He was subjected to what would amount to torture by today’s standards. My father's emotional scars directly affected me and the rest of my family. He never got adequate help and carried around this severe trauma during my childhood. When my own psychiatrists found out that my father had been in mental hospitals they tried to convince me my problems were genetic brain malfunctions correctable by medication. Not once did they ever ask me about my own childhood experiences of trauma, or make the connection of how this might be behind my difficulties. It wasn’t until later that I learnt that there is no solid science behind blaming genetic predispositions and chemical imbalances, and that childhood trauma can play a big role in what gets labelled as mental illness. The testing they did in the hospital led them to give me a diagnosis of schizoaffective disorder, a form of schizophrenia. I was encouraged to see myself as a broken invalid, to forget my strengths and instead focus on my weaknesses and vulnerabilities as evidence of being a defective human being. I learned to fear what was inside me as signs of my disorder, and to turn over authority of my mind and experience to doctors and therapists. Everything became a symptom. I remember telling my hospital psychiatrist I was reading existentialism and Marxist philosophy, and later I found out that he had put this down in my medical record as a form of bizarre behaviour. My treatment plan instructed me to give up my passion for activism and organising. When I tried to talk about my sexuality and being bisexual, they told me that my feelings were part of my disorder. And then I got lucky! I began working with a psychiatrist who decided to listen to me! After discussions with a multidisciplinary team and more information, I have decided and agreed that a course of medication will form part of my overall recovery. I have the following questions and was informed that you would be the best person to answer them. 2.6 Before Hyun Joo starts the medication, how will he know if it is actually working and how long will it take before he notices its effects? 2.7 Hyun Joo is nervous about unwanted side-effects, particularly those that affect his ability to read demanding literature. What are the possible unwanted effects of the medication he will be prescribed, and if he experiences unpleasant side-effects what should he do? 2.8 Is there research that outlines the long-term effects and the addictive properties of the medication? What does the research say, and how can Hyun Joo access it? 14 Working with Service users – Practitioner level Learning module – electronic version 2.9 Hyun Joo’s psychiatrist agrees with him that he needs help in dealing with his childhood trauma. He has already started talking therapy, but would like some advice on other non-medication-based therapies that might be helpful. What types of treatment would you recommend for trauma and how would he access more information about them? Madison’s story I am 22 years old, and I work as a bank teller in the city. I had completed my honours in accounting and was looking at a trainee auditor position in a local firm. It was during this time that I found myself in hospital again. Only this time, it was different. This time I felt it would be difficult for me to return to the workforce, as I would have to take medication for the rest of my life, and that I probably wouldn’t be able to hold down a job. Any feelings of hope and optimism were pretty much gone. My Buddhist practice stopped and instead of “being aware” of what I was thinking and feeling, I suddenly became consumed and debilitated by my thoughts and emotions. It was also at this point that I began cutting myself again. My doctors’ focus had always been on the bipolar disorder. In discussing this with my family and friends, I learnt that medication is a lifetime sentence with this illness. The medications I have been on are definitely not working or helping me. Aside from the severe side-effects that I experienced, the fact that I kept ending up in hospital was a pretty good indication that medications weren’t my solution. I asked my psychiatrist to let me stop all of my medication. He wasn’t keen. However, I have now been off the medication for four weeks and I have clearer thought processes, including my memory recall. I am able to access my analytical thinking process and my general health is improving. I was told that you would be able to suggest other ways that could help me stay off medication. The advice of my colleagues, friends and family has been far more important to me. 2.10 Madison can and has identified some of her strengths already. She has amazing information gathering and analytical skills as well as strong interpersonal skills. Can you think of a few ways she may be able to use these strengths to support her recovery? 2.11 Madison’s spirituality was an important factor in her life and she wants it to be so again. How can she do this? 2.12 Madison has already decided that staying off medication is a challenge she is prepared to take on. However, she knows there will be other challenges. In your view, what are the three priority challenges she might need to overcome and what strategies can you suggest? 15 2.13 Madison’s support networks have been great when she became unwell, but are limited in strategies to help her cope. If she became really unwell, can you suggest ways her support networks can continue to support her if her ultimate decision is to continue not to take medication? 16 Working with Service users – Practitioner level Learning module – electronic version 3 Therapeutic relationships and partnership Relationship building skills are essential to ensure that service users’ prospects of recovery are maximised. The ability of mental health and addiction professionals to build effective relationships has proven critical in assisting the recovery of service users and promoting their safety (Barnett & Lapsley, 2006). There is a range of important relationship building skills required by staff in mental health and addiction services. Staff must have and communicate empathy that is coupled with effective communication and listening skills. The ability to converse openly and honestly helps promote connection and build rapport. The most important factor in building relationships is a mutual respect between staff and service user; both must acknowledge that respect for diversity in language, culture, gender, sexuality and world views are important aspects of building the relationship. A therapeutic relationship is defined as any professional relationship that aims to foster and promote healing and growth in another person. [A therapeutic relationship] … aims to foster and promote healing and growth in another person. Such a relationship is founded on several basic therapeutic tenets: these include respect, unconditional positive regard, trust, honesty and empathic understanding. Such a relationship also requires that the worker demonstrates a commitment to developing self-awareness through reflection and thoughtful sensitive self-enquiry (Stickley and Freshwater, 2008, p. 440). 17 3.1 Several beliefs, principles or values underpin a therapeutic relationship. Choose three from the list below and explain how you demonstrate these when working alongside service users. Respect Trust Empathetic understanding Unconditional positive regard Honesty Commitment to developing self-awareness Feature of a therapeutic relationship Demonstration in practice 3.2 Consider the stories of Paul, Hyun Joo and Madison in Section 2. For each of these people, identify one feature of the therapeutic relationship that you believe is the highest priority in working for that person, and state your reasoning. Provide two examples of interactions or conversations you might have to illustrate the use of this feature with this person. Establishing and maintaining a therapeutic relationship with Paul Feature Two examples of interactions or conversations 18 Working with Service users – Practitioner level Learning module – electronic version Establishing and maintaining a therapeutic relationship with Hyun Joo Feature Two examples of interactions or conversations Establishing and maintaining a therapeutic relationship with Maddison Feature Two examples of interactions or conversations 19 4 Partnership tools Partnership is about making decisions jointly. It is about doing things together, with a common goal. It is a two-way process, though the contribution of each participant need not always be equal. Your role is essentially that of support. It is the service user who takes the leadership role. Effective partnership entails the following guiding principles. Cooperation Exploring alternatives Openness Equity Duties Working together Effectiveness Relationship satisfaction Enjoyment Dialogue Compromise Role sharing Rights and obligations Common ground Honesty Problem solving Respect Creativity Innovation 4.1 List three guiding principles that a recovery plan would include if it were: Service user driven Identifying only strengths Solution focussed 4.2 Locate completed forms or documents that you have used to support service users in planning for their recovery. Reflect on the areas identified in the review of the plan with the service user. Explain how well the plan worked to help the service user to achieve the following. Experience hope and optimism For example, the service user is asked to set their own goals and is encouraged to articulate and write about their dreams and aspirations. These are only shared if the service user wants to share them. Make sense of their experience Access and use information Manage their mental health 20 Working with Service users – Practitioner level Learning module – electronic version Know how to access preferred services Advocate for their rights Belong to the culture and lifestyles with which they identify Fulfil their goals, roles and responsibilities Maintain personal relationships Contribute to healthy whānau 4.3 Does the planning document used in your work setting include questions about physical health? If so, what aspects of physical health are considered? If not, how can they be included? 4.4 In the space provided, draw a diagram and explain the relationship between mental health and physical health. 4.5 Give two examples to demonstrate how you, as a staff member at practitioner level, support and integrate the physical health of the service user in an overall plan for recovery. Example one Example two 4.6 Consider how it would feel if you had to take medication that gave you headaches, caused you anxiety, and made you feel nervous, disoriented, nauseous and confused. What thoughts would be going through your mind? 4.7 How would this affect your decision to continue taking the medication? 21 4.8 Staff at practitioner level will recognise and acknowledge varying social, cultural, psychological, spiritual and biological causes of mental health and addiction. In the following table, list three examples of each type of potential cause. Social 1. 2. 3. Cultural 1. 2. 3. Psychological 1. 2. 3. Spiritual 1. 2. 3. Biological 1. 2. 3. 22 Working with Service users – Practitioner level Learning module – electronic version 4.9 Describe an evidence-based intervention. 4.10 What therapies or interventions are considered routine in your work setting? 4.11 What therapies or interventions are considered alternative in your work setting? 23 5 Practice knowledge 5.1 As part of your development and learning as a staff member at practitioner level, you have been asked to prepare a teaching session for junior staff or staff who are new to their role working in mental health and addiction. You have been provided with the following objectives: provide an introduction to the mental health and addiction sector give an overview of current approaches to mental illness and addiction list alternative interpretations of mental illness give an explanation of the definitions and categories of medications. Using the template, provide one activity that would assist you in teaching each of the key objectives. Objective Supporting activity to teach key objective Provide an introduction to the mental health and addiction sector Give an explanation of the definitions and categories of medications Give an overview of current approaches to mental illness and addiction List alternative interpretations of mental illness 5.2 Give one example of how you would assess one of the objectives above, by completing the following sentence. At the end of this activity you will be able to 24 Working with Service users – Practitioner level Learning module – electronic version 5.3 Read Samuel’s story and answer the questions that follow. Samuel’s story Samuel is 28 years old. He is a second generation, New Zealand-born Samoan. He lives in Porirua, Wellington, with his mother, two elder sisters and younger brother. He is currently single and has a part-time job. Samuel is contemplating study. He has always enjoyed repairing and maintaining machines, and thinks he would like to become a motor mechanic. Samuel first presented to mental health and addiction services at the age of 17 and has had several admissions since then. He has a history of substance abuse. However he denies this abuse to his fanau and church community. His dad left when he was very young. Samuel remembers the last time he saw his dad and the argument his dad had with his mother. Samuel recalls his dad saying that it was because of her “crazy family, the family curse and the history of wrongs they had committed” that he just couldn’t stay any longer. Samuel’s mother has been struggling financially to support her family and when Samuel’s health deteriorates this puts a strain on the family’s personal and financial resources. Recently she contacted you in your capacity as Samuel’s care coordinator with concerns that he had been acting strangely, mumbling to someone although no-one else is in the room, picking at sores that had developed on his arms, and being outwardly aggressive to his brother. You have been asked to speak with Samuel. In your discussions with him, he has indicated that he would like to live on his own for a little while and that sharing a room with his brother is awkward, even though he has been doing so for all of his life. He has also expressed an interest in a young female member of his church congregation, and believes he would have more chance of advancing their friendship if he were more independent. He has also indicated that he would like to discontinue taking medication, because it makes him fat, dizzy, and disorientated. It also interferes with his thinking processes and he needs “a clear head in order to enrol at the wānanga”. Give two examples of assessment processes that your service currently uses to establish Samuel’s needs, and identify potential goals that you could negotiate and agree with Samuel. The goal Assessment process one Assessment process two 5.4 What initial treatment would you suggest for Samuel? Initial treatment Explanation for this approach 5.5 What alternative therapies may benefit Samuel? therapies 5.6 How will you assess, identify and address the risks that Samuel may be exposed to? 25 5.7 Medication is one treatment that may assist service users in their recovery. Disabling or unpleasant side-effects of medication can be a significant disincentive to its use. In order for service users to want to continue using medication, they need information and reassurance that satisfies their concerns. Reflect on service users you have worked with who have been prescribed medication for each of schizophrenia, bipolar disorder or depression. Complete the following templates. Service user diagnosed with schizophrenia Medication used Reason Recognised adverse effects Adverse effects reported by service user What interactions or conversations did you have with the service user alerting you to concerns about taking the medication? Identify the service user’s concerns about taking medication, and how were these addressed. Reflect on how you addressed the identified concerns. Did this make a difference to the service user? If yes, explain. If no, what would you change so that it did make a positive difference for the service user? 26 Working with Service users – Practitioner level Learning module – electronic version Service user diagnosed with depression Medication used Reason Recognised adverse effects Adverse effects reported by service user What interactions or conversations did you have with the service user alerting you to concerns about taking the medication? Identify the service user’s concerns about taking medication , and how were these addressed. Reflect on how you addressed the identified concerns. Did this make a difference to the service user? If yes, explain. If no, what would you change so that it did make a positive difference for the service user? 27 Service user diagnosed with bipolar disorder Medication used Reason Recognised adverse effects Adverse effects reported by service user What interactions or conversations did you have with the service user alerting you to concerns about taking the medication? Identify the service user’s concerns about taking medication, and how were these addressed. Reflect on how you addressed the identified concerns. Did this make a difference to the service user? If yes, explain. If no, what would you change so that it did make a positive difference for the service user? 28 Working with Service users – Practitioner level Learning module – electronic version 5.8 The use of alcohol and other drugs can sometimes alleviate the adverse effects of medication. Consider the chart below. Choose two of alcohol, nicotine, caffeine and marijuana, and explain the effects they can have on the following medication categories. Choice one: alcohol, nicotine, caffeine or marijuana Typical and atypical antipsychotic Antidepressants Anxiolytics Mood stabilisers Anti-cholinergic agents Choice two: alcohol, nicotine, caffeine or marijuana Typical and atypical antipsychotic Antidepressants Anxiolytics Mood stabilisers Anti-cholinergic agents 29 References and recommended reading Barnett, H., & Lapsley, H. (2006). Journeys of Despair, Journeys of Hope. Wellington: Mental Health Commission. Chapman, J., & White, T. (1995). A Guide to Effective Consumer Participation in Mental Health Services. Wellington: Ministry of Health. Deegan, P. (1995). Recovery as a journey of the heart. Paper presented at Recovery from Psychiatric Disability: Implications for the training of mental health professionals. Retrieved from: http://www.uow.com.au/content/groups/public/@web/@health/documents/doc/uow042403.pdf Durie, M. (1994). Whaiora: Māori health development. Auckland: Oxford University Press. Dyall, L., Bridgman, G., Bidois, A., Gurney, H., Hawira, J., Tangitu, P., & Huata W. (1999). Māori outcomes: expectations of mental health services. Social Policy Journal of New Zealand, 12, 71-90. Lapsley, H., Nikora, L.W., & Black, R. (2002). “Kia Mauri Tau!”: Narratives of recovery from disabling mental health problems. Wellington: Mental Health Commission. Mental Health Advocacy Coalition. (2008). Destination: Recovery: Te ungaki uta: Te oranga. Auckland: Mental Health Foundation. Mental Health Commission. (1998). Blueprint for Mental Health Services in New Zealand. Wellington: Mental Health Commission. Mental Health Commission. 2000. Realising Recovery: Through the education of mental health workers. Recovery-based competencies and resources for New Zealand. Wellington: Mental Health Commission. Mental Health Commission. (2001). Recovery Competencies for New Zealand Mental Health Workers. Wellington: Mental Health Commission. Mental Health Commission. (2004). Our Lives in 2014: A recovery vision from people with experience of mental illness. Wellington: Mental Health Commission. Mental Health Foundation. (2002). Building on Strengths: A new approach to promoting mental health in New Zealand/Aotearoa. Auckland: Mental Health Foundation. Ministry of Health. (2002a). Building on Strengths. Wellington: Ministry of Health. Ministry of Health. (2002b). He Korowai Oranga: Māori health strategy. Wellington: Ministry of Health. Ministry of Health. (2002c). Pacific Health and Disability Action Plan. Wellington: Ministry of Health. Ministry of Health. (2002d). Te Puāwaitanga: Māori mental health national strategic framework. Wellington: Ministry of Health. 30 Working with Service users – Practitioner level Learning module – electronic version Ministry of Health. (2005). Te Tāhuhu: Improving mental health 2005–2015. Wellington: Ministry of Health. Ministry of Health. (2006). Te Kōkiri: The mental health and addiction action plan 2006–2015. Wellington: Ministry of Health. Ministry of Health. (2007). The National Drug Policy 2007–2012. Wellington: Ministry of Health. Peterson, D. (2007). I Haven’t Told Them, They Haven’t Asked: The employment experiences of people with experience of mental illness. Auckland: Mental Health Foundation. Repper, J. & Perkins, R. (2003). Social Inclusion and Recovery: A model for mental health practice. Edinburgh: Bailliere Tindall. Stickley, T., & Freshwater, D. (2008).Therapuetic relationships. In T. Stickley & T. Bassett (Eds.), Learning about mental health practice (pp 439-462). New Jersey: Wiley and Sons. UK Drug Policy Commission Recovery Consensus Group. (2008). A Vision of Recovery. London: UK Drug Policy Commission Recovery Consensus Group. Websites Health and Disabilities Commission – www.hdc.org.nz. Human Rights Commission – www.hrc.co.nz. Mental Health Commission – www.mhc.govt.nz. Mental Health Foundation – www.mentalhealth.org.nz. Ministry of Health – www.moh.govt.nz. Office for Disability Issues – www.odi.govt.nz. Privacy Commissioner – www.privacy.org.nz. 31 Working with service users – practitioner level Learning Review Tool and Individual Professional Development Plan Learning Review Tool Using the Likert scales below, rate your work in relation to working with service users. I have a variety of strategies on hand when working within and across the differing sectors that make up the mental health and addiction community. 1 2 3 4 None actually 5 More than five I have a sound understanding of the impacts that mental health and addiction policies have on the strategies that I use when working with service users. 1 2 3 4 5 No idea at all Absolutely I can articulate confidently what recovery is, and explain the benefits to people experiencing mental distress or a loss of well-being. 1 2 3 4 No idea at all 5 Like I invented it I understand and can explain the key principles involved in forming and maintaining therapeutic relationships with service users. 1 2 3 4 No idea at all 5 Absolutely Choose your response to one of the above statements, and explain why you made this response. 33 What new knowledge or insights have I gained from working through this module? What are three things that I can put into practice or improve on as a result? A B C 34 Working with Service users – Practitioner level Learning module – electronic version Individual Professional Development Plan Working with service users – practitioner level What is one thing that I can take personal responsibility for? Action Timeframe Resources Challenges What will I do? When will I do this? What or who will I need? What barriers or resistance will I face? What is one thing that I can advocate for and work towards? Action Timeframe Resources Challenges What will I do? When will I do this? What or who will I need? What barriers or resistance will I face? Please retain this Individual Professional Development Plan: working with service users (practitioner level) to contribute to your summary action plan once you have completed all of the learning modules. 35 36 Working with Service users – Practitioner level Learning module – electronic version