Capítulo 6

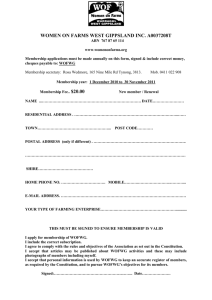

advertisement

THE BRAZILIAN CHARTER OF FUNDAMENTAL RIGHTS: A BRIEF INTRODUCTION. Working paper written for the II Courting Justice IBSA Conference, Delhi, April 28-29, 2008 Sponsored by Ford Foundation Oscar Vilhena Vieira Fundação Getúlio Vargas Escola de Direito – São Paulo Conectas Direitos Humanos SUR – Human Rights Univeristy Network Introduction 1. Transition to democracy, and the Constitutional Assembly. 2. The Reactive Constitution. 3. Fundamental Principles of the Constitution. 4. The Brazilian Charter of Fundamental Rights. 5. General Regime of Fundamental Rights. Introduction This paper has a very modesty propose. It aims to offer to foreign readers a brief introduction to the Brazilian Charter of Fundamental Rights. The paper is divided in five sections. The first one describes the context in which the 1988 Constitution was produced; the second section depicts the result of the constitutional assembly as a reactive constitutions against a immediate past of authoritarian rule and a long history of inequality and search for development; a third section brings attention to the fundamental principles that organizes the Brazilian polity, in which fundamental rights are immersed; the fourth section analyses the content of the Brazilian Charter of Rights; and finally, the fifth section provides some information regarding the regime of rights adopted by the 1988 Constitution. 1. Transition to democracy and the Constitutional Assembly After a slow and gradual process of transition to democracy, the Brazilian society adopted a new constitution in October of 1988. This lengthy process called “abertura” (opening) imposed by the military regime, began with the adoption of an amnesty law, in 1977, which benefited both sides of the political spectrum, allowing the return of left wing dissidents to Brazil, and leaving impugned those involved in human rights violations . The regime also restructured the party system, liberalizing the creation of new political parties and reestablishing the parties that were abolished by the military coup in 1964. This distension of the political system caused the fragmentation of opposition parties (Skidmore, 1988: 447-433). In this new environment, civil society organizations became more vocal and critical of the military regime. The Brazilian Bar Association (OAB), under the presidency of Raymundo Faoro, and organizations like Justice and Peace Commissions, in São Paulo and Recife, under the leadership of cardinals Paulo Evaristo Arns and Elder Câmara, were determined to denounce human rights violations and to pressure for democratization and a new constitution. During 1983 and 1984 a significant alliance between opposition parties and major social forces mobilized the whole country to reestablish the right to vote for the presidency, in a free and direct election called “diretas já”. Congress, however, failed to approve the necessary amendment to the 1969 Constitution. This failure resulted in a compromise between the moderate sectors of the military regime and part of the opposition parties that permitted the election of Tancredo Neves and José Sarney, as President and Vice-President, by an Electoral College, forged during the military regime. The enormous social energy frustrated during this process was finally released during the constituent process, called by Congress, in 1985 (by Amendment 25 to the 1969 Constitution). The Constitutional Assembly was elected in 1986 and started to work in January 1987. In fact, it was a congressional Constitutional Assembly. A first draft produced by a “commission of notables,” presided over by Afonso Arinos de Mello Franco, a liberal politician, was abandoned by the Assembly, which decided to start from point zero. Representatives of thirteen political parties, in a very-fragmented environment, made up the Assembly. The majority of the politicians that had been united in opposing the military regime had, however, distinct perspectives of how a new constitutional order should be organized. The participation of social movements, civil society organizations, and interest groups, was massive. More than twenty thousand people circulated through the Assembly every day, in a process that is considered the most democratic moment of Brazilian political life (Coelho, 1988: 43; Whitaker et al, 1989). 2. The Reactive Constitution The result was a constitution that reacted against the immediate experience of arbitrary rule and a long history of social injustice and inequality. Different from the constitutions forged after the fall of the Berlin Wall, in Eastern Europe, or even the post-apartheid Constitution of South Africa, the Brazilian Constitutional Assembly was insular to major international influences. Perhaps the only foreign model taken into account in a more systematic way during the Constitutional Assembly was the socially oriented Portuguese Constitution of 1976. The result was a document that kept our traditional political model: a presidential system within a federalist state. The constitution adopted, however, a clear aspirational drive aimed at coordinating social and economic change. In this sense it attributed to the state a key role in promoting social welfare and economic development. The economic chapter of the Constitution, however, was almost completely reformed in the nineties to adapt to the neo-liberal wave. The text of the 1988 Constitution is extremely ambitious, regulating in detail most aspects of the Brazilian state, economic and social spheres. The original document counts with 250 articles in its main part, and 94 articles as transitory disposition. Many constitutional articles, however, have dozens of clauses, as Article 5, composed of 78 clauses, regulating civil rights. The 1988 Constitution is organized into eight parts (titles), respectively arranged with regard to: fundamental principles; fundamental rights and guarantees; the organization of the State; the organization of the powers; the defense of the State and of the democratic institutions; taxation and budget; the economic and financial order; and the social order. 3. Fundamental Principles of the Constitution In the first title of the 1988 Constitution it is established that Brazil is a Federative Republic, constituted as a democratic rule of law. Among the fundamental principles of the Republic are citizenship, human dignity, and political pluralism. Demonstrating from the beginning its aspirational nature and social drive, the Constitution lays out, as the main objectives to be pursued by the Brazilian state, the following: the construction of a free, just, and solidary society; national development; the eradication of poverty and substandard living conditions and the reduction of social and regional inequality; and the promotion of the public welfare, free from discrimination, arising from race, sex, color, age, and any other clivage. Finally, it establishes a group of principles that should govern the conduct of the Brazilian State in the international arena, among which it should be highlighted: the prevalence of human rights; self-determination of all people; defense of the peace; and repudiation of terrorism and racism. If in the past there was some strong disagreement over the juridical nature of these principles on the part of Brazilian constitutional doctrine, today there is a substantial consensus between jurists and the courts themselves that all these principles have binding force, and that they must be imposed in all spheres of the Brazilian State. Regarding the political configuration of the Brazilian State, the 1988 Constitution kept federal structure, which is comprised of twenty-seven member states and more than five thousand municipalities. The presidential system, inaugurated by the 1891 Constitution, was also preserved in 1988. The principle of separation of powers (with an independent executive, legislative and judiciary) applies both to the national and member-states spheres. Municipalities count only with executive and legislative branches. The democratic principle governs elections far all legislative and executive posts. The nomination of members of the judiciary is carried out, in general, by means of public civil service entrance exams. Only the members of the superior courts, on the federal level, are chosen by a process, which involves nomination by the President of the Republic and ratification by the Federal Senate. Perhaps the major peculiarity of the Brazilian system of separation of powers, in relation to other countries, is the status and attributions conferred to the Attorney Generals office, organized both at the national and member-states level. According to Article 127 of the Constitution, the Attorney Generals office is responsible for defending the legal order, the democratic regime and the inalienable social and individual interests. In this sense it does not act only in criminal prosecution, as in many other countries, but exerts a representative role for the public interest. Given its administrative and financial autonomy, and the guarantees of independence insured to its members, mimicking the prerogatives of the judiciary, the Attorney Generals office emerges as a quasi fourth power in the Brazilian political system. 4. The Brazilian Charter of Fundamental Rights Reversing the traditional order of the Brazilian constitutions that, since the Empire (1824), placed the charter of rights in the final part of the text, the 1988 Constitution brought the charter of rights to the beginning of the text, thus symbolizing that these rights should be understood as presupposed in the exercise of power. The title of rights and fundamental guarantees is divided into twelve articles. The first of these, Article 5, is currently composed of seventy to eighty clauses (normative statements), Article 6th to article 11th address social rights, which are taken up at length in the constitution, from article 193 to article 215, when it is addressed in detail the rights to health, social security, social welfare, education, culture, etc. Articles 12 and 13 refer to nationality. Articles 14 to 17 address political rights and the rights of the political parties. Article 170 deals with economic rights, and article 150 establishes taxpayers’ rights. In the following sections a brief description of the rights expressed by the Constitution will be made. 4.1. Civil Rights The fifth article of the Constitution basically recognizes all civil rights established by the international legal order. It recognizes the rights of equality and nondiscrimination; it guarantees the freedom of conscience, expression (excluding censorship), belief, demonstration, work and association; it guarantees intimacy and the secrecy of correspondence; it insures the right to material and non-material property, provided its social functions are observed, and guarantees the right of inheritance; it establishes, as well, a long list of rights related to due process, beginning by the principle of legality; it insures the right to access the judiciary in the case of violation of or threat to a right; it guarantees free judicial assistance provided by the state; it ensures the right to substantial legal defense, to due process (sensu strictu), to reasonable duration of the legal process, presumption of innocence, and prohibits evidence obtained through illicit means; it prohibits, finally, torture, the death penalty and other punishments of a cruel nature. Article 5 additionally establishes diverse remedies, or constitutional actions, concerned with the protection of fundamental rights, which are: habeas corpus; habeas data, to guarantee access to information about oneself; the “mandado de segurança”, to protect all other rights not secured by habeas corpus or habeas data; and the “mandado de inunção”, which is intended to ensure the efficacy of fundamental rights against legislative omission, which impedes the immediate application of rights. 4.2. Social Rights The Brazilian Constitution defines, in its sixth article, social rights as the right to education, health, work, habitation, leisure, safety, social security, social welfare, and protection for motherhood and childhood. These rights, however, are divided into two large blocks. The first of them, regulated from the 7th to the 11th article of the Constitution, refers only to the area of work relationships. They are rights of the worker on an individual level, such as protection of employment, a work environment free of discrimination, the minimum wage, a workday not greater than eight hours, holidays, maternity and paternity leave, etc., and rights related to the organization of the working class, such as freedom to form unions and the right to strike. Workers’ rights are directly opposable to the employer and assured by the labor courts . Other social rights are found dispersed throughout the Constitution. They are distributive rights, directly opposable to the State. The criterion for the distribution of these distinct rights differs in each case. The right to health is recognized by Article 196 of the Constitution, as an universal and egalitarian right. The right to social security, protected by Article 201, in turn, has a contributive nature, which depends on contributions made by the worker himself, the employer and budgeting by the Union. The right to social welfare, shaped in Article 203, should be assured in respect to the necessities of each individual, not dependent on prior contribution. The right to basic education, established in Article 205, is an obligation of the State and has a universal nature. The State should progressively universalize secondary education and ensure, with regard to the capacity of each individual, the access to university education. Also protected are the rights to preschool education for children of up to five years of age, and the rights to education of disable people, preferably in the regular school network. To secure the efficacy of social rights, the 1988 Constitution established mandatory budget allocation clauses. In the case of the right to education, Article 212 of the Constitution stated that the Union would apply never less than eighteen, and the States and Municipalities, never less than twenty-five percent of tax revenue on education. In the case of the right to health, a formula linking social expenditures to revenue was also created; in this case, however, the Constitution determines that a complementary law should establish a percentage, for a period of five years. The establishment of mandatory investments on social rights, for spheres of the federation, had a strong impact on public spending in the social sector. It is estimated that the 1988 Constitution imposed on the Brazilian State an increase of more than 40% in social spending, when compared to the previous system. From the decade of the eighties to the year 2000, social indicators demonstrate a rise in life expectancy, from 62.5 years to 72.5 years; a reduction in the mortality rate from 69.1/thousand children, to 30.1/thousand children; as well as a reduction in the illiteracy rate, from 31.9% to 16.7% of the total population.1 The rights to habitation and public safety, outside of statements at the end of the sixth article of the Constitution, don’t receive a clear delimitation in the length of the Vanessa Elias de Oliveira, Política Social no Brasil: da cidadania regulada à universalização regressiva – assistência social, educação e saúde, in Introdução à Política Brasileira, Humberto Dantas e José Paulo Martins Junior, orgs., São Paulo, Paulus, 2007, p. 224. 1 text. In the same way, outside of there being a chapter on agrarian reform, the Constitution did not define a right to access to land, but only authorized the State to carry out expropriation, of unproductive properties which did not fulfill their social function (Art. 184), with the objective of promoting agrarian reform. The Constitution also established a group of fundamental rights in the area of culture, imposing on the State obligations to expand and democratize access to cultural resource and cultural manifestations; a duty to protect popular, indigenous, and afro-brazilians cultural manifestations; a duty to preserve ethnic and regional diversity; responsibilities in the protection of historical and cultural heritage; and an obligation to establish incentives for the production, promotion and diffusion of culture (Art. 215 and 216). In its environmental plan the Constitution ensured to everyone the “right to an ecologically-balanced environment,” regarding it as a public asset of the people and essential to a healthy quality of life, as something that must be preserved for future generations. Through this intergenerational pact, the 1988 Constitution imposes on the State and subsequent generations, a clear obligation to preserve and restore the environment, the diversity and integrity of the inherited public space of the country; to define and protect areas of preservation; to require a previous environmental impact study in relation to activities that are potentially harmful to the environment; to control the production, commercialization, and employment of techniques that possess a risk to life, to quality of life, and to the environment; to promote environmental education; and to protect flora and fauna. 4.3. Economic Rights The 1988 Constitution, by means of Title VII, constructs the legal framework for the Brazilian economic system. From a perspective of fundamental rights, the Constitution ensures the right to property, conditioned by its social function. Thus the power to use, enjoy, and have property at one’s disposal is conditioned by its conciliation with other values that are also constitutionally-protected, such as the environment, the rights of the consumer, free competition, the reduction of inequality, labor rights, and favor of a dignified existence and social justice (Art. 170). In this sense the right to property and the free exercise of free economic activity, ensured by Article 170 of the Constitution, fits into the context of a State that receives constitutional power to regulate the economic activities, reprimanding the abuse of economic power that gives rise to “the domination of the markets, the elimination of competition and the arbitrary increase of profits” (Art. 170, Para. 4). In the area of taxation, the Constitution establishes a series of taxpayer rights. Only those taxes which have been previously authorized by the Constitution can be instituted. Moreover, their collection and increase will always depend on law enacted on a previous fiscal year. The Constitution also bans the creation of taxes with a confiscatory nature. It is important to point out, however, that the Constitution states that whenever possible taxes will have a “personal character and will be graded according to the economic capacity of the taxpayer…” (Art. 145, III, Para. 1). This provision is fundamental in understanding the mechanisms of redistribution of wealth instituted by the Constitution, by means of social rights. 4.4. Political Rights Citizenship rights are extended to all Brazilians, native or naturalized. There are, however, some limitations for naturalized citizens, with respect to the posts they can hold. The formal tool of participation is the universal vote, with equal value to all. Citizens have rights to participate in the electoral process, as voters or candidates. The illiterate are not allowed to run for office. The elections for the legislature and the executive branch at municipal, state, and federal levels are direct and carried out every four years. With the exception of senators that have a mandate of eight years, all other elected posts have a mandate of four years. There is also the possibility of citizens’ direct participation through plebiscites, involving referendums and popular initiatives for the proposal of laws. These instruments of direct democracy, however, depend on legislated authorization, which has largely been restricting its use in the Brazilian political system. Political rights cannot be suspended, except in cases of cancelation of naturalization, by judicial decision; absolute civil incapacity; criminal condemnation conferred through a final judicial decision; refusal to meet universally-imposed public obligations or render a required service, as in the case of military service; or in cases corruption. There is freedom to create political parties, provided that they respect the principles of national sovereignty, democracy, pluralism, and the fundamental rights of human beings. The political parties must have a national character, and are prevent from having a paramilitary nature or from receiving funds from foreign entities or governments. Political parties are ensured autonomy in defining their internal structures and access to resources of the public party fund, as well as free access to radio and television, conforming to the guidelines of the law. The 1988 Constitution established, through Articles 118 to 121, a speciaized Electoral Court system, that has the responsibility to monitor the electoral process. 4.5. Rights of Vulnerable Groups The Constitution makes express reference to three vulnerable groups that receive specific constitutional treatment: children and adolescents, indigenous peoples, and the elderly. The rights of children and adolescents to life, health, food, education, leisure, professionalisation, culture, dignity, freedom, and familial and community care have “absolute priority,” according to the text of Article 227 of the 1988 Constitution. This is the only moment in which the constitutional text prioritizes a specific group of rights. It is the obligation of the State, of the society, and of the family to place children and adolescents safe from all forms of negligence, discrimination, exploitation, violence, cruelty, and oppression. In 1989, Law No. 8.069 was edited, establishing the Statute for Children and Adolescents. This statute describes, in detail, the rights and guarantees of children and adolescents, besides establishing a special jurisdictions for monitoring these rights. The Constitution also recognized the right of indigenous peoples to their specific social organizations, customs, languages, beliefs, traditions and judicial representation. In this aspect, it put an end to centuries of a State tutorial practice that in effect eliminated any possibility of autonomy for the native Brazilian communities. The Constitution even ensured to native Brazilian rights to their traditional lands. This gave rise to a long process, full of conflict, of land demarcation. The remnants of Quilombola communities, or, that is, descendents of slaves that formed communities in the time of slavery, were also ensured rights to traditionally lands, consistent with what is outlined by Article 68, in the Acts of the Transitory Constitutional Dispositions. Finally, even if there is no further reference to vulnerable groups, the Constitution confers on the State, on society and on the family, in a generic manner, the task of supporting elderly persons. 5. General Regime of the Brazilian Fundamental rights Charter The general regime of application of the fundamental rights was basically organized by three paragraphs (clauses) set in the end of article 5. The first paragraph (article 5) establishes that fundamental rights are to have immediate application, independent of further legislative regulation. It is not a matter of crystal clear understanding, given that a large number of constitutional clauses expressly require complementary legislation, or demand a complex set of public policies to secure the proper implementation of fundamental rights. This mechanism was conceived, however, as a guarantee against the omission of the legislator or the administrator. The most acceptable interpretation to this paragraph states that fruition of fundamental rights does not depend on ordinary legislation, so that the omission of the ordinary legislator does not work as an excuse denying rights to a person. This independence does not mean however that the ordinary law does not have a central role in the outlining of a specific right, especially when they clash with each other. But in the absence of ordinary legislation, the judiciary is authorized to directly extract from the Constitution the content of the fundamental rights to be applied to a concrete case. 5.1. Non-expressed Fundamental Rights The second and third paragraphs of Article 5, in turn, open the doors of the 1988 Constitution to the recognition of human rights not expressed in the constitutional text. The second paragraph reproduces a traditional model of liberal constitutionalism, outlining that the rights expressed in the Constitution do not exclude others resulting from the fundamental principles adopted by the Constitution. This gives the judiciary the possibility of updating the charter of rights without the necessity of constant alteration in the text of the document. On the other hand, the third paragraph, of Article 5, provides that human rights stated in international human rights treaties that Brazil are part of, can be incorporated into the Constitution, provided that the approval of these treaties is given by the National Congress through the same procedure required for the approval of a constitutional amendment. In the event that the approval is given through the standard system of approval for treaties (simple majority), these rights will have the same hierarchy as federal laws. 5.2. Circumstances for that Allows Restrictions of Fundamental Rights With regard to extraordinary circumstances, which authorize the restriction of fundamental rights, the 1988 Constitution established two hypothetical situations: the state of defense and the state of siege. The state of defense is a tool for the preservation and prompt reestablishing of public order and social peace, in restricted and determined locations, seriously threatened or facing imminent institutional instability, or affected by public calamities of grand proportion. It is the responsibility of the President of the Republic to declare a state of defense, after receiving input from the Council of the Republic and the National Defense Council. The decree should be en route in twenty-four hours to the National Congress, who will decide on its validity. A decree that institutes a state of defense will state the length of its duration and will be able to impose restrictions on the rights of assembly, secrecy of correspondence, and secrecy of other communications (Art. 136). The state of siege, in turn, regards situations of serious disturbances at a national level or situations of war. In this case the President of the Republic must ask for prior authorization from the National Congress, in order to declare it. In the case of state of siege, the only measures restricting rights that will be permitted are the following: requirement to remain in a specific place; detention in a building not designated for persons accused of or condemned for common crimes; restrictions related to secrecy of correspondence, communications, and liberty of press; suspension of the freedom to assemble; search and seizure in homes; intervention in the carrying out of public services; and requisition of property (Art. 137 to 139). 5.3. Fundamental Rights as Limits to the Amending Power of Congress Finally, the general system of fundamental rights establishes that a proposal for a constitutional amendment that intends to abolish individual rights and guarantees will not be the object of deliberation by Congress. Through this clause the 1988 Constitution creates a kind of reserve of constitutional justice that cannot be eliminated through the power of the constitutional reformer. According to what the Federal Supreme Court has already decided, in more than one circumstance, the fundamental rights constitute material limits to the power of constitutional reform, enabling the Court to invalidate amendments passed by the National Congress.