WORD97 - zagarins.net

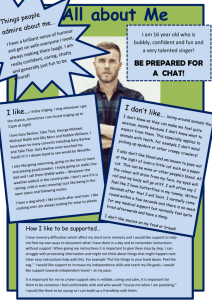

advertisement