Spring 2002

advertisement

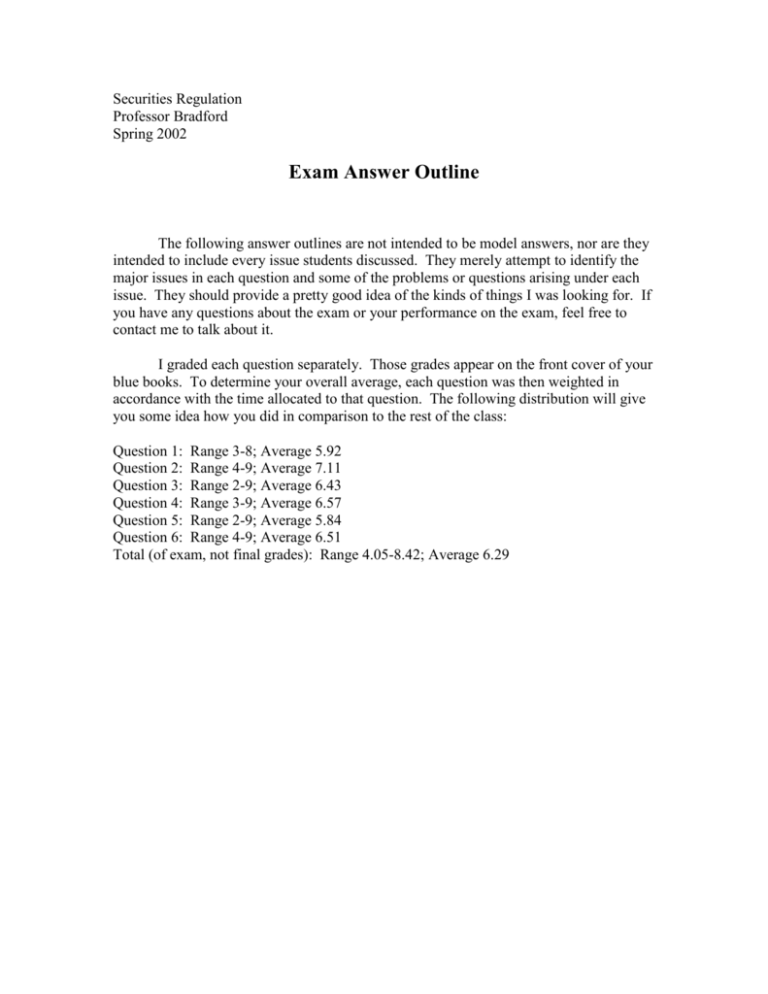

Securities Regulation Professor Bradford Spring 2002 Exam Answer Outline The following answer outlines are not intended to be model answers, nor are they intended to include every issue students discussed. They merely attempt to identify the major issues in each question and some of the problems or questions arising under each issue. They should provide a pretty good idea of the kinds of things I was looking for. If you have any questions about the exam or your performance on the exam, feel free to contact me to talk about it. I graded each question separately. Those grades appear on the front cover of your blue books. To determine your overall average, each question was then weighted in accordance with the time allocated to that question. The following distribution will give you some idea how you did in comparison to the rest of the class: Question 1: Range 3-8; Average 5.92 Question 2: Range 4-9; Average 7.11 Question 3: Range 2-9; Average 6.43 Question 4: Range 3-9; Average 6.57 Question 5: Range 2-9; Average 5.84 Question 6: Range 4-9; Average 6.51 Total (of exam, not final grades): Range 4.05-8.42; Average 6.29 Question 1 An omission or misrepresentation is material “if there is a substantial likelihood that a reasonable shareholder would consider it important” in deciding how to act. TSC Industries. Here, the amount of the change by itself does not appear material. President’s $10,000 change is relatively inconsequential in relation to Inrut’s total assets of $100 million. A reasonable shareholder would probably not consider a $10,000 difference such as this important. However, other considerations might make the misrepresentation material. For one thing, absent President’s change, Inrut would have been in default under the Piggy loan agreement, which would trigger the full $10 million liability. That amount probably would be material, but only if the default was not waived. The possibility of an unwaived default is an uncertain future event that would be analyzed under Basic’s probability/magnitude test. The magnitude is relatively high—the $10 million loan balance represents 1/10 of Inrut’s total assets. Finding that much cash on short notice could seriously disrupt Inrut’s business. However, the probability is relatively low. Piggy has twice waived similar defaults and has indicated it will continue to do so in the future as long as, as is true here, Inrut is “close.” It’s not clear how a court would decide this given the relatively high magnitude and the relatively low probability. Basic says the two must be balanced, a rather imprecise process. There is another potential argument for materiality. President found it fairly easy to get into and alter Inrut’s accounting records. That reflects on the reliability of Inrut’s accounting controls. Although this change was relatively small, such easily accessible accounting records could allo future changes of a much larger magnitude. Moreover, President’s actions reflect on his integrity. His willingness to engage in accounting fraud, particularly when coupled with the lack of accounting controls, is something an investor would probably consider important. The deception here was small, but the likelihood of greater deception in the future could be important to a reasonable investor. Given these additional considerations and the marginal outcome of the Basic test, a court would probably decide that this misrepresentation was material. Question 2 A. Ordinary stock is a security. Landreth. However, an investment is not a security merely because it is called “stock.” Forman. The Landreth rule applies only to instruments with the ordinary characteristics associated with common stock: the right to receive dividends, negotiability, the ability to be pledge or hypothecated, voting rights in proportion to share ownership, and the capacity to appreciate in value. Landreth. This “stock” does not have any of those characteristics. Nor is this a security within the Howey investment contract test. There is no expectation of profits. B. Assuming that the stock is otherwise a security, Ima has purchased a security. The section 3(a)(11) exemption is irrelevant to whether an investment involves a security. It exempts offerings of securities from the Securities Act registration requirements, but it is still a security that Ima is purchasing. C. Ima did not purchase a securtity. The stock may still be a security, but Ima did not “purchase” it. Section 2(a)(3) defines “sale” as “every contract of sale or disposition of a security or interest in a security, for value.” The term “purchase” is not defined, but presumably it is the mirror image of “sale.” this was a gift. Ima gave no value for the stock, so she did not purchase it. Question 3 Rule 144 is available for these securities. Ash is not an affiliate because it does not control the issuer, Magna. See Rule 144(a)(1). Thus, Rule 144 is available to Ash only if the securities sold are “restricted securities.” Rule 144(b) applies to “Any affiliate or other person who sells restricted securities of an issuer for his own account.” These are restricted securities under either Rule 144(a)(3)(i), because the original offering was a sectionn 4(2) private offering, or Rule 144(a)(3)(iii), because Ash acquired the securities in a Rule 144A transaction. Current Public Information. A couple of the conditions to the availability of Rule 144 are problematic. First, the issuer, Magna, must meet the current public information requirement of Rule 144(c). Magna is not a reporting company, so 144(c)(2) applies. The specified information about Magna must be “publicly available.” That condition is probably not satisfied because Magna is very secretive and does not even provide reports to its own shareholders. Volume Limitation. The quantity limits of Rule 144(e) are also problematic. Ash is not an affiliate, so the limits in rule 144(e)(2) apply. The amount of all restricted securities of Magna sold by Ash in a three-month period may not exceed the greater of 1% of the total amount outstanding or the average weekly trading volume. See Rule 144(e)(1)(i), (ii), and (iii). The average trading volume is only 100 shares, and 1% of the amount outstanding is 1,000 shares, so Ash may not sell more than 1,000 shares in any threemonth period. Ash exceeded this limit. From January 5 to March 2 (within 3 months), Ash sold 600 + 150 + 300 = 1,050 shares. Other Conditions. Ash appear to have met the other requirements of Rule 144. Ash sold the shares in brokers’ transactions as required by Rule 144(f) and defined in 144(g). His broker was involved and there was no solicitation. Ash has also held the shares over a year, so the one-year holding period in Rule 144(d) is met. The problem doesn’t indicate if Ash filed the notice required by Rule 144(h); it would be required to file because it sold more than 500 shares in a three-month period. Rule 144(k). Rule 144(k) terminates all of these restrictions for sales by “a person who is not an affiliate” if “at least two years has elapsed since the later of the date the securities were acquired from the issuer or from an affiliate of the issuer.” Ash clearly is not an affiliate, so the first condition is met. The second condition is more difficult. It has clearly been more than two years since the issuer sold the securities. They were sold on April 1, 1999, and it is now 2002. However, if Lava is an affiliate, it has not been two years since the securities were acquired from an affiliate. If so, Rule 144(k) is unavailable. An affiliate is one who, among other things, controls the issuer. Rule 144(a)(1). Control is the direct or indirect power to control the management and policies of the issuer, “whether through the ownership of voting securities, by contract, or otherwise.” Rule 405. Lava’s only connection to Magna is that he owns 25,000 of 100,000 shares, not a majority. However, no one else owns more than 1,000 shares, so Lava’a ¼ ownership may be sufficient to give him control. More information is needed about the dynamics of Magna’s shareholder voting and whether Lava is able to get his nominees on Magna’s board. Conclusion. If Lava is an affiliate, it has not been two years since the shares were acquired from an affiliate of the issuer, and 144(k) is not available. In that case, Ash’s sales did not comply with Rule 144 because the sales did not comply with the volume limitations in 144(e) or the public information requirement in 144(c). If Lava is not an affiliate, 144(k) is available and Ash’s sales complied with Rule 144, since the conditions would not apply. Question 4 A. Bill is an acceptable purchaser in a Rule 506 offering. Bill is an accredited investor as defined in Rule 501(a)(6). His joint income with his spouse was more than $300,000 in each of the two most recent years and he has a reasonable expectation of reaching that same level this year, since Hillary’s annual salary is $350,000. Rule 506(b)(2)(ii) provides that a purchaser in a Rule 506 offering must have “such knowledge and experience in financial and business matters that he is capable of evaluating the merits and risks of the prospective investment. Bill knows nothing about finance or business, so he clearly would not meet this requirement. However, the requirement only applies to a purchaser “who is not an accredited investor.” Rule 506(b)(2)(ii). Since Larry is an accredited investor, he does not need to meet that requirement. B. All of the investors are accredited investors because they have net worths in excess of $1 million. rule 501(a)(5). This won’t exceed the 500-purchaser limit in Rule 506(b)(2)(i) because accredited investors don’t count toward that limit. Rule 501(e)(1)(iv). However, Rule 506(b)(1) says that Rule 506 offerings must satisfy all the terms and conditions of Rules 501 and 502, and Rule 502(c) says that an issuer may not sell the securities “by any form of general solicitation or general advertising.” To avoid a general solicitation, the SEC staff has indicated that the issuer must have a preexisting relationship with the offerees that would enable the issuer to be aware of the offeree’s financial circumstances. The issuer here is confident that the millionaires are accredited investors under Rule 501(a)(5), but, since the issuer does not have a preexisting relationship with all 500 of the club members, this is probably a general solicitation. Question 5 Even assuming this is a material misrepresentation, there are still several issues with respect to Goober’s liaiblity under Rule 10b-5. Primary Liability. The first issue is whether Goober is a proper defendant in a Rule 10b-5 action—whether he is a primary violator. This is a private action by the stock purchasers, so aiding and abetting liability is unavailable. Central Bank. There are two possible tests for primary liability: the bright line test and the substantial participation test. Goober need not directly communicate the misrepresentation to the purchasers to be liable, but, under the bright line test, he must make a material misrepresentation with the expectation that it will be communicated to the purchasers. Here, Goober clearly is responsible for the misstatement. The ad was accurate until he changed it. But, technically, the statement in the ad is Upchuck’s, not Goober’s. Goober might not be liable under the bright line test because the statement was not attributed to him. See Wright v. Ernst & Young. However, this might also be seen as an indirect statement by Goober, in which case he would be liable, even under the bright line test. Under the substantial participation test, Goober would probably be liable because he is directly and culpably responsible for the misstatement. Scienter. The second issue is whether Goober acted with scienter. He did not know the true test results, so it’s hard to argue he intended to defraud. However, this appears to be recklessness of the worst sort. He made the statement not knowing (or caring) whether or not it was true, and he knew the danger of misleading investors. “In Connection With.” A third question is whether the statement is “in connection with” the purchase or sale of the securities. According to Texas Gulf Sulphur, the statement must be “reasonably calculated to influence the investing public.” The statement did not appear in the registration statement or in any other offering materials, but in a product advertising. It certainly was not directed at investors. It was, however, reasonably foreseeable that investors might see and rely on the advertisement, particularly while the public offering was ongoing. Some investors did in fact rely on the ad. There is probably a sufficient nexus between the statement and the sales of securities, especially since Upchuck was directly involved in the sales. Transaction Causation. Another issue is causation, both transaction causation and loss causation. None of the purchasers appear to be able to show direct reliance. Even those who saw the ad admit they would have purchased anyway, although the ad bolstered their decision. Thus, to recover, the purchasers must rely on Basic’s fraud on the market theory. Upchuck is traded on the New York Stock Exchange, so the market is an efficient one, and the false statement was public. Thus, the misstatement should be reflected in the market price. However, the statement was in an ad, where the tendency to puff is known, so the market would discount the statement. Moreover, the true test results were also publicly available, although buried in an FDA filing. Under efficient market theory, that publicly available statement should also affect the market price. If Goober can show this, he may be able to rebut the fraud on the market presumption. This is similar to Wielgos, although Wielgos involved the issue of materiality. Loss Causation. The final major issue is loss causation. The loss was a result of the health problems related to use of the drug, not its success rate. Nothing in the trials even raised any health concerns. The purchasers would have had the same loss whether the success rate was 40% or 60%. Thus, the loss causation required by section 21D(b)(4) of the Exchange Act does not appear to be present. Question 6 A. Section 5(b)(1) of the Securities Act makes it unlawful to use, among other means, the mails, “to carry or transmit any prospectus relating to any security with respect to which a registration statement has been filed . . . unless such prospectus meets the requirements of section 10.” Broker used the mails to send this prospectus, so the jurisdictional test is met. This is clearly a “prospectus,” defined as a written offer to sell. Section 2(a)(10). However, this is a preliminary prospectus that meets the requirements of section 10, so it doesn’t violate section 5(b)(1). Rule 430 says that the prospectus filed as part of the registration statement meets the requirements of section 10 of the Act for purposes of section 5(b)(1) prior to the effective date. Rule 430(a). B. This note is a prospectus. Sending it violates section 5(b)(1). The term “prospectus” includes any letter or communication that is written which offers any security for sale. Section 2(a)(10). This letter is a written communication. It offers the debentures for sale because “offer for sale” includes “every attempt or offer to dispose of, or solicitation of any offer to buy,” a security for value. Section 2(a)(3). Broker’s note clearly is soliciting Mona to buy the debentures. The free-writing exception in section 2(a)(10)(a) is not available because Broker never sent Mona a prospectus meeting the requirements of section 10(a), the final prospectus. The only complication is the Gustafson case. This is a registered public offering, so it’s within the context Gustafson says is covered by the term “prospectus.” However, Gustafson also says that a prospectus is a document of wide dissemination that contains essentially the information required by section 10(a). This letter is an individual communication that does not contain such information. Thus, Gustafson might be read to exclude it. However, the key focus in Gustafson was on the private nature of the offering, so this letter is probably considered a “prospectus” even after Gustafson.