Slide Summary (final)

advertisement

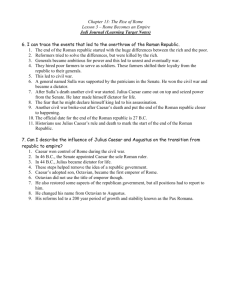

General Slides Slide 2.2 Title: Detail of Botticelli's "Death of Lucretia." Lucretia was raped by a noble. She tells the story of what happened and then kills herself. Brutus slays him and rids Rome of the Monarch. This was the beginning of the Republic, and the tradition of the apprehension of a monarch over Rome. This piece shows Brutus lamenting over Lucretia's body. Brutus later uses this event as propaganda on a coin to prove he is a defender of the Republic and that his actions against Julius Caesar should be justified. Slide 2.3 Roman republican man holding the portrait busts ["imagines"] of his ancestors. This speaks of the fiber of roman politics. It was tradition to raise your authority in the eyes of politicians by accentuating your associations with already powerful or well respected individuals. Here the roman politician is broadcasting his ancestry to add to his own validity. The importance of this procedure relevant to Augustus is how he in his early years in order to gain validity and influence accentuated his relations with Julius Caesar. Virgil furthers these glorified associations in the Aeneid by emphasizing the emergence of the Julian family from the original founders of Rome. Slide 2.4 View of the Senate house ' Curia ' in the Roman forum The Senate was a pillar of the Republic tradition of Rome. They embodied the believed superiority of the Roman governmental style. This type of government and tradition was challenged many times but unsuccessfully until Augustus. He pursued his way into a monarch position while at the same time supplying the appearance of a return to the original traditions of the Republic. This is what is so amazing about the reign of Augustus. He was able to accomplish two totally opposing agendas for his gain with little notice in the Senate. Slide 2.6 Portrait bust of Cicero, most famous of the "new men" of Rome and most famed orator of the late Republic. Full Name: Marcus Tullius Cicero Lived 106BCE - 43BCE. His career in politics is remarkable b/c he did not come from the usual line of top leaders. His family was not of immense wealth or fame. He remained a true supporter of the Republic through the times of Julius Caesar. A law was passed stating any man who killed a roman would be exiled automatically and was to be retroactive. This was specifically called upon in order to rid the Senate of Cicero by a loyal Caesar follower. Orated the Philippics in support of the senate after the death of Caesar. He supported Octavian to use him as a puppet to get back the senate. After Antony was defeated Octavian had him killed. Slide 2.8 Portrait bust of Julius Caesar. Sim. to Zanker fig. 5. Julius Caesar laid the foundation to the upset of the senate and the emergence of a monarch type leader that Octavian would soon take advantage of. He adopted Octavian in his will issued after his murder on the ides (15th) of March 44 BCE. Born in 100BCE. After his death Octavian took the opportunity to defeat Antony and "restore" the republic. His line was commemorated in the Aeneid by Virgil. Slide 2.9: Portrait bust of Pompey the Great (55 BC) Interestingly, in this bust, Pompey’s hairstyle resembles that of Alexander the Great from whom he borrowed his title, “the Great.” This bust was created after the creation of the first triumvirate in 60 BC (along with Caesar and Crassus) and before Pompey’s defeat at Pharsalus following a war with Caesar in 48 BC. Professor Tarrant cited the conflict and competition between Caesar and Pompey’s personal ambition and military success (as exemplified here with Pompey’s comparison to Alexander the Great) as one of the major forces bringing Rome to its “breaking point.” Slide 2.12: Coin of Julius Caesar (45 BC) As we learned from our section papers, coins were an extremely powerful form of propaganda. Both of these coins issued by Caesar exemplify his desire to express his own authority. The wreaths worn in each coin by Caesar are a symbol of authority. On the top coin, the inscription reads “Dictator for the fourth time” and on the bottom “Dictator forever” (a claim Caesar made after defeating all opponents in 44 BC). Octavian followed Caesar by making coins in order to increase his popularity among the Roman populace but learned from his father’s mistakes as well. Octavian used his coins to portray himself as a ruler among and for the people, rather than the supreme dictator (the year Julius Caesar proclaimed himself “Dictator forever” happened to be the same year he was assassinated). Slide 3.2: Coin of Brutus (44 BC) Brutus, the man who led the conspiracy against Caesar, in what he termed as a fight for freedom and “liberty,” is pictured here on his own coin following the overthrow and assassination of Julius Caesar. In other coins he has the inscription “Cap of Freedom.” Essentially he tries to free himself from the dictator role which Caesar had assumed (much like Octavian does later) and instill a belief that he has brought liberty to the people. There is much controversy surrounding Brutus’ and the conspirator’s true motives since Julius Caesar had gained the support and love of the majority of the people (the issue was probably the liberty of the Senate). Also of note, Octavian will openly hate Brutus and all others involved in his father’s murder throughout his entire life. Slide 3.3: Coin of Octavian (38 BC) In this coin of Octavian, two important methods of propaganda employed by Octavian are shown. First, on the obverse Octavian is pictured with the inscription with “Son of the deified one” and the Julian Star. These references and connections to Julius Caesar by Octavian are meant to further his own status by association. For, by declaring Caesar to be divine in 42 BC, Octavian hoped to get rid of his prior reputation as a dictator, as well as use his father’s “new status to enhance his own” (Lecture III notes). On the reverse, there is a similar reference to Caesar in addition to the inscription, “the civic crown.” As seen in the Res Gestae and other sources, Octavian loves to stress how he has been elected and is serving the people in as many ways as possible – therefore, it seems fitting for him to refer to his position as the “civic crown.” Slide 3.5: Triumviral coins of Octavian and Lepidus Octavian, Lepidus and Antony composed the second triumvirate created in 43 BC. Just another way in which coins served as a means of political propaganda – in a sense, solidifying the formation and promoting the future success of the triumvirate. Of note, these coins do not exist for members of the first triumvirate because that was “a wholly unofficial arrangement,” while the second triumvirate was a “legally sanctioned office that could be publicly advertised” (Lecture III notes). COINS: Certainly not neutral representations, but tools of propaganda 3.1 Obverse: Head of Brutus, Inscription Reverse: Cap of Freedom, daggers Interpretation of the assassination of Caesar. Printed under the auspices of Marcus Brutus. Gives the traditional republican view of Caesar’s assassination. Obverse bears inscription “IMP” for Imperator, holds the office of general or military commander. On reverse, inscription refers in abbreviated form to the Ides of March, the season known for Caesar’s assassination. Two daggers represent the act of the conspirators (assassination). The cap of freedom or liberty, representative of the transition of a man from slavery to freedom, was used in the ceremony to mark a man’s freedom. In this symbol we get the assertion that the Senators who killed Caesar transformed Romans, who had been slaves under Caesar, had been set free. “How can you be against freedom?” But we must ask ourselves who was being set free. It was a subsection of the Senators whose interests were endangered by Caesar who were most “enslaved” by Caesar. -Senate had ultimate authority to authorize coinage. Senate would then set up a triumvirate to oversee production and distribution of coins. Those triumvirs might have strong political ties and loyalties, which would guide the coinage they saw produced. Plutarch tells us that Caesar, when he died, fell at the foot of Pompeii’s statue. Pompeii depicted as guardian of senate Caesar as violator of Senate’s rule BUT, in reality, Pompeii was as much a symptom of the breakdown of the Republican system as Caesar. If Pompeii had one, the Republic still would not have persisted. Pompeii took office prematurely, skipped curses honorum. 3.2 Obverse: Head of Woman, “Libertas”, Reverse Brutus and his attendants, inscription “Brutus” Marcus Brutus issuing a warning in the mid 50’s that the Brutus clan, the first to establish consul, is still going to act to protect libertas and freedom. Probably a warning directed towards Pompeii. Caesar was the first to put his image on a coin. After his death, EVERYONE does it, follows suit. The anonymity that once tempered the use of images on coin was never pursued. Now that Caesar was gone, what next? VACUUM where Caesar had been, strong loyalties to the man and the name persisted. POWER of the name, of the figure. Hundreds of Senators would have remained loyal to Caesar, owed their positions to him. There was a Caesarian power base that existed in wait of a leader. Two potential leaders step forward to claim it. MARC ANTONY: The Obvious successor, defender of Caesar’s legacyAlready had the loyalty of the army, served as co-consul with Caesar. At the time of Caesar’s death, Antony is the man to watch. Cicero transferred his hatred and opposition of Caesar to Antony. Started attacking Antony in speech after speech “philippic oration” GAIUS OCTAVIUS: age 19 when Caesar is killed in 44- was a great-nephew of Caesar Was in Albania in a mix of study and military training at time of assassination. Had started to become close to J.C. MARC ANTONY in the prime of life OCTAVIUS still a kid 2 things happen to turn the tables in Octavius’ favor: 1) The will of Caesar is revealed with Octavius as the heir to his enormous fortune. and as his adopted son. He takes the name of Caesar, becoming Octavianus and Caesar. His friends and allies call his Caesar, while opponents like Cicero continue to call him Octavian. 2) Change in Julius Caesar’s position divine association. In his final years he had a priest responsible for his image, with sacrifices made to him. Summer of 44 (after assassination) a comet was observed during games in his honor. His supporters took that as a sign of his divinity, and were able to get an official proclamation of divinity, with J.C. as divus. Thus, Octavian is now the son of a deified one. All coins Octavian produces from here on make reference to this divine element, with Octavian as “Divi Filius,” son of the divine one. Sometimes with J.C. on obverse and Octavian (Caesar) on reverse. Octavian portrayed at times with beard, sign of MOURNING. Depicts him in mourning of father, as loyal, devotional son. Octavian associates himself with Caesar on coins when it is useful 3.3 Obverse: bearded head of Octavian, Divi Filius inscription, sidus Iulium: the star or comet that was evidence of J.C’s divinity.Reverse: Laurel (“corona civica” the civic crown) with inscription DIVOS IULIUS, “the deified Julius. From 38 BC. 3.4 (Series) Octavian on obverse, Venus on reverse. Venus as ancestress of Octavian. Venus victorius, “victrix,” with shield, helmet, spear. On the shield of Venus is the star, sidus Iulium. From before 31 BC. in 43, an official alliance of triumvirate is established to manage the state. Is a form of three-person dictatorship. Third person is Marcus Lepidus, one of Caesar’s army commanders. Authorized for five years, to be a temporary situation. Was renewed in 37. One of more notorious moves of triumvirate is proscription list means of paying back scores. Lands and fortunes seized. Antony demands that Cicero be a prominent victim of proscription. Alliance of Octavian and Antony was a shaky and difficult one. Each wanted sole power. Fought as much as they were in accord. Antony expansive Octavian calculating, cautious 3.6 Octavia featured on reverse of coin of Antony. REVOLUTION had only been five years since first appearance of a living Roman on coinage. Now a woman is on a coin. Commemorates Antony’s marriage to sister of Octavian, Octavia. Octavia is the cement meant to link Antony and Octavia. On other coins, depicted as superimposed faces. 40 BC. Even so, Antony is cultivating a relationship that had already formed between Antony and Cleopatra. Coins are the venue used to shape the purely Roman image of Octavian and the changing Egyptian image of Antony. 3.6 This coin shows Octavia, the sister of Octavian and the wife of Antony. At that time, there was a triumvirate in which Antony, Octavian, and Lepidus ruled the state, and Antony and Octavian did not get along. Marriage was a traditional Roman practice for creating a link between people, so in 40 BC, Antony married Octavia. Only five years before this coin, Caesar was the first person to place any Roman man's portrait on a coin, and so this was a revolution in Roman coins because now a woman was featured on the obverse. 3.7 This is a portrait of Fulvia, the second wife of Mark Antony. Antony was married to Fulvia and married Octavia after she died. In the war of Perugia, Octavian's forces beseige Fulvia and Antony's brother Lucius. War would have begun between Antony and Octavian, but the troops refused to fight (many had fought together earlier) and so they reconciled--Treaty of Brundisium. Then, after Fulvia died, Antony married Octavia to "seal the arrangement" 3.8 Superimposed, overlapping images of Antony and Octavia in a way similar to that in which the king and queen of egypt might have appeared on a coin. Shows the link between Antony and Octavian that was created through this marriage. The reverse is difficult to see. 3.9 Jugate coin of Ptolemy and Arsinoe. This coin shows Ptolemy and his wife and sister, Arsinoe. Brother-sister marriages were accepted in Egypt and the Ptolemeis did it for many generations. The coins read "Divine Siblings". The relation of this coin to Octavian is, most likely, that the style of the jugate coin is used by Antony and Octavia in many coins to show their relationship (for example, 3.8). 3.10 This coin shows Antony on the obverse and Cleopatra on the reverse. Even while Antony was married to Octavia, he was pursuing a relationship with Cleopatra, and as the 30s progressed, his interests in Egypt were becoming more and more prominantly displayed on coins. This coin is one of many depicting Cleopatra and Antony. Although some "admirers of romantic poetry" were thrilled that he had the courage to put Octavia and Cleopatra on coins, his depiction of Cleo also fueled the propaganda of Octavian and his followers. 3.11 The capture of Egypt. On obverse, Octavian. On reverse, Egyptian crocodile and inscription AEGYPTO CAPTA (“with Egypt captured”). Coin from after 31, when Octavian defeats Antony and Cleopatra at Actium. most dangerous moment in a person’s life is the moment of triumph and victory, when power is at its peak. This is visible in the life of Caesar. By 32, Octavian is in the position that Caesar was at the time of his death in 44. 3.11 Coin of Octavian minted after the Battle of Actium in 31 when Octavian defeated Antony and Cleopatra. Inscription on the obverse: CAESAR COS VI, “Consol for the 6th time.” Shows how Octavian still used the names of traditional republican offices. On the reverse: a Nile crocodile and the inscription: AEGYPTO CAPTA ("with Egypt captured") Important because battle is depicted as foreign victory, not civil war, since Antony had so fully associated himself with Cleopatra. 4.1 Aureus (gold coin) from 27 BC, the year Octavian becomes Augustus. Inscription reads: CAESAR DIVI F[ILIUS] COS VII = "Caesar, son of the deified one, consul for the seventh time." Advertises that consulship is a traditional position (though Octavian held it many times more than was traditional). 4.2 Coin of Augustus, 27 BC. Obverse: portrait. Reverse: eagle carrying corona civica, a wreath given to him by the Senate as a military decoration for saving the lives of citizens, and inscription AUGUSTUS, showing that he incorporated his name into the coinage as soon as the name was conferred to him by the Senate. (for more info, see similar coin in Zanker fig. 76) 5.2 Portrait bust of Marcus Agrippa, c. 30-20 BC. This is a portrait bust of Marcus Vipsanius Agrippa, one of the main advisers to Augustus. Agrippa had been the admiral in charge of Augustus' forces at the Battle of Actium - indeed, by most accounts he won the battle - and was later given the responsibility for most of Augustus' building programs. For a time, he was Augustus' most obvious successor, and he was clearly the second man in the state - evidenced from his position on the Ara Pacis Augustae. When Augustus became princeps of the new principate, he shaped an administration that relied heavily on a stable group of advisors, of which Agrippa was probably the foremost. Agrippa was also significant because Augustus married him to his daughter Julia in 21 BC and adopted him as his son-in-law, desiring to produce an heir. The marriage produced five children (Agrippa Posthumous, Agrippina, Gaius, Lucius, and Germanicus), however none of them became his heir. The existence of this bust is testament to Agrippa's importance - he was portrayed in art and immortalized for posterity. 5.3? Segment of the south processional frieze of the Ara Pacis Augustae showing members of the imperial family--could that be Maecenas peeking over a shoulder? 13-9 BC This picture depicts a segment of the Ara Pacis Augustae (Altar of Augustan Peace) monument (dedicated in 9 BC). The monument depicts a procession following the royal family. The segment shown is of the imperial family, but the figure in the background, looking over the shoulder of the person in front of him, may represent Gaius Clineus Maecenas, one of Augustus' chief advisors. Maecenas was a major behind-the-scenes presence, and was active mainly in domestic and cultural affairs, famously known as the patron of Virgil and Horace. Maecenas (as well as Agrippa) were insiders who knew Augustus from his youth, but as men from non-elite backgrounds they were typical of many whom Augustus attracted to public life. 5.4 Fragment of a papyrus roll found in Egypt containing elegiac verses of C. Cornelius Gallus, poet and onetime prefect of Egypt. (70-26 BC.) This is a fragment of a papyrus roll found in Egypt containing elegiac verses of C. Cornelius Gallus (70-26 BC), poet and onetime prefect of Egypt. Those who were successful under Augustus knew not to enhance their own glory at his expense; Cornelius Gallus did not get this message. He was forced to commit suicide in 27-26 BC, and his case illustrates the new limitations on ambition in the new principate. As a poet, he is considered part of the second generation of poets following the novi poetae, which included Virgil and Horace. It is ironic to note that the Egyptian obelisk in the center of St. Peter's Square (in the Vatican, one of the most visited places on earth) is inscribed with the name of Gallus, who desired to be remembered; his name is not visible. 5.6 Temple in Ankara, Turkey: site of a bilingual (Greek and Latin) version of the Res Gestae inscribed on its walls. This picture depicts a temple in Ankara, Turkey, which was the site of a bilingual (Greek and Latin) version of the Res Gestae inscribed on its walls. The significance of the temple is that it represents the fact that Rome, while a Republic in name, was actually a de facto Empire. The Res Gestae (the Accomplishments) was written by Augustus and completed in the last year of his life (14 AD). In it, Augustus glorifies his political and military endeavors, as well as his service to the people; it's inscription on a Turkish temple is evidence of Augustus' widespread influence and the propagandizing that occurred throughout the Roman empire. Slide 5.7 Temple in Ankara, Turkey: site of a bilingual (Greek and Latin) version of the Res Gestaeinscribed on its walls Temple of Rome and Augustus at Ankara, the capital of modern Turkey, contains the best-preserved copy of the Res Gestae, Aug. statement of his achievements. The exterior of the wall is covered with a Greek translation of Res Gestae, making it most accessible to the citizens. The interior of the wall has it in the original Latin text. This is sign of the political and cultural influence of the Roman Empire spreading to the provinces outside of Italy. The mode of Roman architecture was very wide spread. Temples like this is a way of visually recalling the fact that Rome was spreading its control over much of the Mediterranean world. Slide 5.9 Aqueduct: Pont du Gard, France. Built perhaps when Agrippa governor in Gaul, late 1st century This aqueduct was part of the Aug.’s building program in the provinces to display Roman control. The Pont du Gard was made by Agrippa, August's son in law, in 9 BC. It was used to supply drinking water to the city of Nîmes from a hill that's only 90 meters high, hundreds of kilometers away. The long, slow descent requires the aquaduct to cross the Gard River, which is the most impressive part of the structure. Here, the structure reaches a height of over 40 meters over the river, giving it great technical and aesthetic importance. The bridge is made up of three tiers of arches: the first is made up of 6 arches (142 meters long), the second has 11 arches (242 meters), and the third has 35 small arches (275 meters). The entire bridge is constructed of yellow stone blocks weighing 6 tons each. Slide 5.10 Statue of Augustus from Livia's villa at Prima Porta. Copy in marble of a bronze statue, after 20 BC This statue of Augustus at Prima Porta is a very famous image of him. It is the image of him as an ideal imperator or commander-in-chief. He is wearing a military breastplate and holding a staff of command in his left hand. He raises his right hand in the gesture of addressing his troops. On the breastplate is an image that was carefully chosen. A Roman soldier with a hunting dog at his feet and a more exotically dressed man wearing trousers, tunic and a beard is holding up a standard with an eagle at the top. The foreigner is a Parthian and he was depicted kneeling. This relates to Aug. success in recovering the legionary standard lost to the Parthians by Crassus in 53 BC. This was the result of diplomatic negotiations, but Aug. depicts it here as a victory over the Parthia, as if the Romans forced the Parthians to give back the standard. The statue is used as an advertisement of Aug. as a great command/general; in reality Aug. is not very good with military matters. Most of the victories won were by Agrippa and Tiberius. But it is important that Aug. has the image of a military commander, since military success is directly correlated with political success and it is expected that the imperator as commander-in-chief will be a great general. SLIDES 5.11 Breastplate after 20 BC. Depicts Parthian returning the Roman legionary standards lost by Crassus in 53 BC. Twists real story: diplomatic negotiations occurred, not victory over Parthia. From statue of Augustus in Livia’s villa at Prima Porta. Military success part of princeps image. Statue showed Augustus the general as ultimate dux (leader). See Lecture V notes, Zanker fig. 148 a-b. 5.12 Coin shows kneeling Parthian returning Roman legionary standards. Inscription: CAESAR and SIGN[..] RECE[PT..] = "the standards received." 19 BC. Same motive as 5.11. See Lecture V notes, Zanker fig. 146. 6.1 Portrait bust of Livia, second wife of Augustus. From the proud Claudii family. 1st of a number of powerful imperial wives and mothers. See Lecture VI notes. Slide 6.3 Theater dedicated to Marcellus, adoptive son of Augustus, 13 BC Marcellus, son of Octavia, making him effectively A's nephew [mirroring A's own relationship with Julius Caesar] was a clear favorite of A's, and was his marked heir. A married Marcellus off to Julia [A's daughter] in 25 B.C.; unfortunately, Marcellus died in 23 B.C. The death of Marcellus is also documented in Virgil's Aeneid -- in Book VI when Anchises is telling of a young man who grieved the nation when he died, showing the extent to which A depended on Marcellus to be his heir. The theater of Marcellus was built in 13 B.C., ten years after Marcellus' death, probably to commemorate him as A's adopted son. A word on theaters -- the theatre of Marcellus was the only other theatre in Rome, apart from the theatre of Pompey; A loved theatres, because when he did go in, he was among the masses, symbolic of the leader addressing his people directly. It also gave an image of popular support, since it could seat 12-15,000 people. It was a center for high culture -- Roman plays and poetry would be read here, and A attended often [juxtaposed with Caesar, who attended, but read letters all the time]. Finally -- as with many other objects of architecture during the Augustan period, by naming buildings after his family members, A created a ubiquitous presence for his family in Rome -connotations of being dynastic and immortaility. 6.4 Coin with Augustus on obverse and Marcus Agrippa on reverse. Agrippa is wearing a "naval crown." c. 12 BC. Sim. to Zanker fig. 168. Agrippa, as other descriptions of him have mentioned, was considered, with maecenas, one of "those closest to" A. Agrippa was A's star general, helping in the war of Perugia, Naulochus, and Actium; not only a great general, but also a faithful supporter, a public benefactor, the author of an autobiography... he basically devoted all his energies ot the glory of Rome and its empire, the emperor and the dynasty [becoming part of it himself, in his marriage to Julia and 21 BC]. He was the chosen heir after marcellus' death; unfortunately, he died in 12 BC, which is when this coin was minted, suggesting that the coin was produced in memory of Agrippa, not only fantastic general [as evidenced by the ship-crown on his head] and benefactor of Rome, but also good friend and right hand man to Augustus. The reason for the ship-crown is likely to be commemorating Agrippa's naval victory against Antony and Cleopatra at Actium. The fact that Agrippa's profile is feature on the reverse of Augustus' reflects the closeness of the two men. 6.7 Julia, daughter of Augustus. The woman who helped secure all of Augustus' heirs, but ended up being a huge pain in his life because of her adulterous ways [in the face of A's marriage laws and hopes to restore morals to the republic]. First married Marcellus in 25 BC, then when Marcellus died in 23 BC, she married Agrippa in 21 BC, and when Agrippa died in 12 BC, she married Tiberius in 11 BC; finally she was banished by Augustus in 2 BC. She provided Augustus with more heirs in her short marriage with Agrippa, producing five children: Gaius, Lucius [both boys whom A adopted into the Caesarian family], Agrippina, Julia the younger [who was also promiscuous and was banished as well], and Agrippa Postumus [apparently a disgrace to the family because he was slow and indolent, and eventually was murdered during Tiberius' reign to secure T's own position of power]. 6.8 Coin with Augustus on obverse, Julia flanked by Gaius and Lucius on the reverse. Sim. to Zanker fig. 167b. Julia was daughter of Augustus, married to Marcellus, Agrippa, and Tiberius. Gaius and Lucius were Julia’s sons, and apparent heirs to August, until both died young and within two years of eachother. Julia was exiled for adultery in 2 BCE. 25 Augustus' daughter Julia marries A.'s nephew Marcellus 23 death of Marcellus 21 Julia marries Agrippa; 20 birth of Augustus'grandson Gaius Caesar (son of Julia and Agrippa); 17 birth of Augustus' grandson Lucius Caesar (son of Julia and Agrippa), adoption of Gaius and Lucius by Augustus; 12 death of Agrippa; 11 Julia marries Tiberius (Livia’s son by previous husband) 5 B.C. Gaius designated as consul five years in advance; 2 B.C. Lucius designated as consul five years in advance; Augustus' daughter Julia banished for adultery with Iullus Antonius (son of Mark Antony) and others; 2 A.D. death of Lucius; 4 death of Gaius, Augustus adopts Tiberius 6.9 Cameo of Livia and Augustus (14 AD = posthumous). Livia has the attributes-wheat, poppies, and diadem, of the goddess Ceres. Zanker fig. 184. Livia was A’s third (and final wife). Ceres was the Roman goddess of growth and fertility, identified with Greek Demeter. Ceres had a cult following in Rome. Notes on Livia from lecture: “Livia a clear winner: her son Tiberius now Princeps, her own status enhanced; given title "Augusta," position somewhat like that of Queen Mother but with more ability to influence policy. Livia the first of a number of powerful imperial wives and mothers, cf. Agrippina the mother of Nero (granddaughter of Julia and Agrippa). Roman ambivalence about a woman with great power may account for hostile tradition about Livia, image of her as scheming or murderous. 9.1 Reconstruction of Pompey's theater, dedicated in 57 BC (first permanent theater building in Rome) in honor of Pompey the Great (of Pompey-Caesar-Crassus fame). Tarrant discusses this slide in context of comparing poets’ desire for fame and permanence to that of political leaders. Poets at this time often referred to their poems as “monuments”. (Catullus refers to Cinna’s Smyrna as a “small monument,” and Horace compares his poems to the pyramids in Odes. Slide 9.2 The tomb of a wealthy freedman (a baker), resembling in shape a large granary. An example of how individuals sought lasting memory through monuments, even after death. This baker must have worked his way up through life to create such an expensive very individual celebration of his job and life. This mentality of trying to reach gloria/fame through lasting monuments/achievements created tension in the Augustan world: personal political ambition (example Cornelius Gallus) was not tolerated by Augustus. Reference slide 5.6, of the obelisk with Gallus' name etched into it. However, poetic ambition flourished and Latin poets sought their own immortality through ever-greater poetic works. Slide 9.3 Reconstructed view of a public library in the time of Augustus. Because the only medium on which poems could be recorded was the highly fragile papyrus scroll, Rome wasn't able to print/copy poems so that they were easily accessible to the public. Instead, they must have been collected at libraries such as these. Scholars would have been forced to travel here to study them; it changed the experience of interacting with poetry in the ancient world, explains why so few of it survives today (fragility of papyrus). Also, a chance to consolidate great poetic works at Rome, centralize culture and a chance for Augustus to extol the cultural superiority of Rome under his reign. Slide 10.3 Enlarged detail of 5th century BC Greek hydria. Painted scenes depict the Sack of Troy. Note: Aeneas carrying Anchises in upper left corner. This is a mosaic of scenes depicting the fall of Troy. Since it is Greek and predates Augustus and Virgil by 400 years, this jar shows that pervasive knowledge and celebration of Aeneas and the events related in the Aeneid already existed long before the Aeneid was written. Thus, Virgil had the opportunity of formalizing the myth and legends that were already circulating, and spinning them to comment on the political career of Augustus. Specifically, the tensions between pessimistic and optimistic readings of the Aeneid, and how the poet's opinion on the methods and legacy of Augustus was not clear-cut. Slides 10.4 – Coin of Julius Caesar: Venus on the obverse; Aeneas and Anchises on the reverse. Aeneas was the son of Venus and the father of Iulus, traditionally seen as the father of the gens Iulia to which Julius Caesar belonged and Octavian/Augustus was linked by adoption. The coin references Caesar’s ties to the divine Venus and the Roman founderfigure, Aeneas; Represents the Roman side of Aeneas (as opposed to the Greek side) (Lecture 11) 11.1 Manuscript of the late 4th/early 5th c. AD (late Antiquity) of Virgil, the beginning of the second Eclogue. “Generalized portrait” of “The poet” of Latin Antiquity -Virgil is pictured at his work with his tools- lectern and papyrus scroll-box (containing rolls of his poetry). Show the fame that Virgil and the Aeneid achieved (Lecture 11) 11.3 From the fourth book, confrontation between Anna and Dido and Aeneas, debating poses. Anacrhonistic illustrations of Virgil’s Aeneid to accompany the text show how important the Aeneid was even to the Catholic Church (Vatican Latium). Virgil seen sort of as a pagan prophet. Show the fame that Virgil and the Aeneid achieved (Lecture 11) Slide 12.1: Phallic votive offering Romans who pray to the gods and subsequently receive benefit would dedicate monument, identifying the area of help, to express thanks. This monument is to express thanks for conception of a child, and was first introduced with a decorous fig leaf hiding the phallus. Slide 12.3 - - This slide is a picture of “The Flying Phallus”. It is significant because it represents the sexuality that was so prevalent in Roman art. While this aspect of Roman art is often excluded from exhibits, it was nonetheless a very prevalent and important part of Roman society. The phallic symbols represent symbols of fertility. Slide 14.1 Bernini’s rendition of Apollo and Daphne (from Ovid’s Metamorphoses) – (1624) Theme of god raping nymph tackled by many Roman wall painters. Image illustrates transformation of textual into sculptural work --Apollo almost has Daphne; however, the desperate Daphne (arms outstretched in desperation) has begun to transform into a laurel tree. Image intended to elicit sympathy for helpless victim? Artist perhaps attempting to illustrate Ovid’s idea that meaning is a construct- depends on whose point of view one focuses on. Possible Augustan links could be suggesting Augustus’ tendency to abuse power, like Apollo, and allow passion to overtake sense of right and decency, victimizing the helpless, like Daphne. Important to remember that what artist focus on important and indicative of intent. Slide 14.3 A 17th century depiction of the rape of Europa by Titian Ovid’s tale of Europa carried off by Jupiter, disguised as a white bull, is an image frequently explored by artists The scene is visualized very clearly, with Europa clutching onto Jupiter’s horn with one hand The action here is advanced, for the bull has moved away from the shore, with the terrified Europa holding the a streaming garment above her head Details of Titian’s rendering correspond to Ovid’s second account of Europa in the tapestry of Arachne: He precisely shows Europa lifting her legs, and desperately trying to keep them out of the water Also the presence of Erotes (cherubs) indicates that Amor is operating within this scene Titian’s depiction illustrates the richness and diversity of perspectives on Ovid’s stories from the Metamorphoses Image 14.4 – “Fall of Icarus” by Pieter Brueghel (16th c.) - image adapted from Daedalus/Icarus myth in Ovid, Book VIII, pp187-190 - illustrates the importance of myths in Ovid’s work (250+ myths!) to artists - BUT Ovid’s and Brueghel’s description seem very different: for Ovid, Icarus’ fall is the central event; for Brueghel, it is a minor detail, easily missed (Icarus is only seen as a tiny pair of legs on the right bottom corner, sticking out of the splashing water!) - Brueghel: everything is calm – the farmer, the ship, the shepherd. Why? - A: could be interpreted as affirmation of Ovid’s true meaning – that one should not be too proud or ambitious. (Hence, Icarus not at the center) - Also, during Renaissance, Icarus myth was often interpreted (following humanist tradition) that Icarus = hero who risked everything for greatness. However, Brueghel, creating this work in the Baroque tradition, reacting against the focus on the humankind, by emphasizing the “smallness” of man relative to the universe. – Slide 15.2 - Archaic Greek kouros from Sounion in Attica, 600-575 BC. This image is of a kouros – a young man, in the Archaic artistic style that was characteristic of Greek art, pre-500 B.C. In the Archaic depiction of people, individuality was not a priority – the statue presents a generic young man with a typical archaic-style appearance of a young athletic man: he has a stylized face, large “handle-shaped” ears, curly symmetrical patterned hair and patterned braids, large blank eyes, (usually, not really shown here but general about kouros, a typical “archaic smile” on his mouth), and abstract and geometric muscles on his torso. The statue is in the typical rigid frontal pose, mid-walk with one leg forward. The archaic style of depicting kouros was so stylized and predictable that usually there was little difference from one statue to the next. This non-naturalistic depiction of the human figure began to be softened in the late Archaic period of the “severe style” which showed greater realism, but this slide shows a typical, standardized, and non-naturalistic kouros. We discussed Greek art in this class as preceding Roman art, and the Archaic style was part of a store of examples of art that could have influenced Roman artists, so it should be studied. Focus was on depictions of the human form. Lecture Slide 15.4 The “Kritios boy”; Greek sculture circa 490 BC; example of the “Classical” period (apprxom 450-350 BC), noted for greater realism in depicition of facial and anatomical features, yet as in Archaic period, figures do not have individually distinctive features Image 16.1 This is a bust of the poet Homer, in the late Hellenistic style (1st century B.C.). The portrayal is realistic, as evident from the “warts and all” style. The poet is depicted with a wrinkled face, balding head, and tossed hair. This bust, is unlike that of Socrates, who is portrayed in the more idealistic classical style. In contrast to Socrates’ bust, this depiction makes Homer appear less dominant and powerful. The style may be attributed to the desire to portray Homer as a venerable figure, and convey the message of gravitas. 16.2 Alexander the great. Coin of Alexander the Great, showing attributes (ram's horns) of the god Zeus Ammon. Alexander was born in 356 BC in Macedonia, the area around present day Thessaloniki in northern Greece. Though the Macedonians might have considered themselves part of the Greek cultural world, the other Greeks might have viewed them as half-barbarians. Alexander's father, King Philip, was an energetic ruler who had started a systematic policy of expanding his kingdom. Philip's main conquest was that of the Greek mainland, after his victory at Chaeronea in 338 BC. Alexander, still in his teens, commanded the Macedonian cavalry during this battle. This coin’s main features: idealization. the rams horns, suggesting deification (godliness) the flowing, long upswept hair (anastole) and feminized features. Beauty is close to glodliness. And damn ain’t he beautiful 16.3 Coin of Ptolemy III of Egypt, with attributes of the gods Helios (sun-ray crown), Zeus and Poseidon the trident (three pronged spear) is illustrative of Poseiden (“Neptune,” to you Greek-educated mythological cats…) again, take note of the scruffy hair. He looks relaxed. A calm leader. 16.4 the "Terme ruler": Life-size statue of Roman general, 150-125 BC. Zanker, fig. 1. This is what we call ‘heroic nudity.’ The exaggeration of the perfect human form, the spear actually helps the statue stand up, so the man can seem to be moving, more animated, rather than flat on his feet. 16.5 Head of Pompey the Great. See lecture 2 as well. Zanker, fig. 6. In the year 60bc, remember the unofficial pact (the wrongly named "First Triumvirate") uniting Julius Caesar, Gnaeus Pompeius (= Pompey the Great), and Marcus Crassus Still, this statue has Pompey with a slightly big nose, a little more realistic. 17.1 Early head of Octavian (37 BC), bearded, from Arles. Keep in mind: Augustus' coins and statues not so much a record of how he looked at any particular time as of how he wished or allowed himself to be seen--a freedom not enjoyed by most modern political figures. These Early coins and statues show Octavian bearded, a symbol or his mourning for Julius 17.2 Coin of Octavian, 38 BC. Obv.: Octavian, bearded, with sidus Iulium(Julian star) and inscription DIVI F[ILIUS] ("son of the deified one.") Rev.: Corona civica ("civic crown") and inscription DIVOS IULIUS ("the deified Julius.") take note of the olive leaves symbolizing peace. Very simple coin. What isn’t there? 17.3 Small intaglio (glyptic art consisting of a sunken or depressed engraving or carving on a stone or gem) showing Octavian as Neptune. Showing him as Neptune, in heroic nudity, suggests a blatant deification of the leader. 17.4 Denarius showing Octavian with foot on a sphere, holding an aphlaston (stern) and staff. Between 36 and 31 BC. Honesty, not really of interest. He’s got his foot on the sphere, great, ‘on top of the world’ we all get the imagery. Not much more to squeeze out of this one. 17.5 Aureus with head of Octavian, now Augustus. Inscription reads: CAESAR DIVI F[ILIUS] COS VII = "Caesar, son of the deified one, consul for the seventh time." 27 BC. He looks young, huh. It’s idealized. 17.6 Prima Porta Augustus. Now we’re talking. This is pretty important. The Augustus of Prima Porta, believed to have been commissioned in 15 A.D. by Augustus’ adopted son Tiberius, is a majestic example of Imperial Roman statuary. Hair meticulously arranged: note stylized grouping of locks on forehead, the signature of this type. One arm outstretched to suggest a look towards the future, change, vision, etc. Nothing overtly dramatic or superhuman; in Primaporta statue divine connections subtly suggested by figure of Cupid, chilling under the statue, looking up at him. Check out the breast plate: lots of good stuff carved in relief. scenes depicting the Roman victory over the Parthians. These scenes were used by Tiberius as a form of propaganda so that the viewer would recall the important role his father played in securing the Roman empire. 17.7 Drawing of statue of Augustus as Pontifex Maximus, with toga drawn up over the head. After 12 BC. Really not that interesting. Don’t waste your time on this one. 18.1 Theater of Pompey. theater complex (55 B.C.) the first permanent theater in Rome; a sign of the increased wealth and ambitions of leaders 18.2 Temple of Apollo on the Palatine(mid-20s B.C.); super important! Augustus' building program larger, more comprehensive, more carefully planned and integrated than anything earlier. Recent availability of high-quality marble from Carrara allows for new level of magnificence; this constructed of ‘white luna marble.’ interesting for location, in heart of the old city and linked to Augustus' own new residence, the ultimate source of the term "palace"; recall Ovid's mischievous reference to Mt. Olympus as "the Palatine of heaven". Temple complex included a major library of Greek and Latin literary classics: as building's architecture links Rome to Greek classical past, union of the two literatures implies Rome's equality with Greece and full assimilation of Greek culture. Also, Link of Library to Temple avoids a "royal" connection. 18.3 Forum Augustus model: check this info: Temple of Mars Ultor (Mars the Avenger) and Forum of Augustus vowed in 42 B.C., not completed until 2 B.C.; Res Gestae 21. Located next to the forum of Julius Caesar, originally a way of proclaiming Augustus’ "avenging" of Julius' death, its message much expanded as project developed, especially after the Parthian "victory" of 20 and the recovery of lost legionary standards. In final form a synthesis of Roman history with Augustus as culmination. Temple itself, elements identifiable through views on coins and allusions in later monuments, e.g., grouping of Mars, Venus, Caesar on pediment. Side "halls of fame" with statues of Roman worthies, based on a simialr feature in Pompey's theatre. Prominent siting of Romulus and Aeneas in semicircular exedrae. Typically eclectic use of Greek decorative elements: classically-styled caryatids, Corinthian column-capitals, copies of famous Hellenistic paintings originally associated with Alexander. 18.4 Complex on the Campus Martius which included the Mausoleum, Ara Pacis, obelisk and ustrinum (funeral pyre base). Mausoleum of Augustus; the earliest of all buildings in this district, perhaps a relic of Octavian's more extravagant self-presentation before Actium. Bigger than the original "Mausoleum" built by Mausolus in 4th c. BC (one of the traditional "seven wonders of world"): 130 ft. high, 280 ft. across, i.e., outdoing the pomp of Hellenistic monarchs A symbol of Octavian's loyalty to Rome and a counter to Antony's rumored wish to be buried in Egypt. During A.'s long life becomes a family resting-place, taking on a dynastic significance. Given new meaning when incorporated into larger complex. Sundial with Egyptian obelisk 100 ft. high as its gnomon ( i.e.,pointer). Dedicated 10 B.C., recalling A.'s victory over Egypt. Theory mentioned by Zanker that sundial pointed to Ara Pacis on A's birthday no longer seems tenable. Remember: Ara Pacis is Augustus’ auto-biography, but it leaves out Julia and all her fuckups 18.5 View of the Forum of Augustus. This is a contemporary view of what it looks like now. Not nearly as preserved as, say, the pantheon. 19.1 The "Room of the Masks" in the House of Augustus in Rome Prominent element in domestic art are mythological scenes relating to "classic" literary texts: Homer, Virgil, Ovid. Remember: Emphasis on picturesque or romantic incidents: Odyssey landscapes, Trojan Horse, ill-fated Ovidian characters such as Pyramus and Thisbe. --Combinations of subjects in "theme" rooms, integration of mythic scenes into architectural settings. 19.2 Bronze statue (Greek) of a youth pressed into service as a candelabra Young Roman boys were known each as a ‘kouros.’ Good word. Score essay points! 19.4 Wall-painting from Pompeii showing the rescue of Andromeda by Perseus. Not very intersting 19.5 Sacro-idyllic" scene from wall decoaration at the villa of Agrippa Postumus at Boscotrecase. 10 BC-10 AD. 20.1 (lots to say on ‘oration’ and public speaking) (though not directly related to the statue itself) Bronze statue from Etruria [i.e. where the Etruscans were from] of an orator, dressed in high Roman boots and a toga. Nicknamed "L'Arringatore" ("the haranguer"). 90-70 BC. Museo Archeologico, Florence. Oratory skill was super-important (think Cicero and how he came from a not-soimportant family and then became a consul, really respected, etc.) So, what’s so important about this dude? Oratory the skill most prized by the Republican elite (along with military success). Oratory considered a form of literature, as shown by the fact that prominent speakers (e.g.,. Cato, Cicero) often published their best efforts. Public speaking central to law and politics: both involve persuading/moving large groups, many political figures also active in legal system; Roman trials large public events; overlap of oratory and theater. Speaking ability also valued in military commanders, cf. Augustus of Prima Porta, shown addressing an imaginary body of troops; speeches before battles a standard feature of Roman historiography. Rhetoric the final stage in the upper-class educational system for men (not for women), after basic literacy and "grammar," i.e., literature; Formal speeches prominent in Latin poetry, e.g., Dido-Aeneas confrontation in Aeneid 4, monologues of Metamorphoses. Romans' high regard for oratorical skill tempered with suspicion/hostility toward glibness, mere technical proficiency, perhaps because rhetoric as a discipline was a Greek product. Rhetorical schools focus on two main kinds of exercise, the imaginary legal case (controversia) where student is given facts and has to argue for one side or the other, and the speech of advice (suasoria) where student advises a historical or mythological character in making a critical decision. For examples of both types cf. Sourcebook, pp. 239-243. A subcategory of suasoria is prosopopoeia or "role-playing," in which student assumes part of a historical or mythological character in a given situation and imagines what that person might have said 21.1 This is from lecture 21 where the professor is commenting on religion in the Rome of Augustus. This is a picture of the household gods, the lares, the penates, of the roman family. Here both the human figures and the sanek are representations of the household gods. In this sense religious practices were pervasive in lives of many-perhaps most—Romans. The household and family would be embodied/symbolized/protected by household gods (lares, penates). This type of representation is a painting that would most likely be place in the entrance of a home. We see a great deal of day to day religious practice of Romans. 21.3 This is a scene on the Ari Pacis of Aeneas offering sacrifice. Significantly juxtaposed with it, not shown in this slide, is a figure of Augustus. In the Ari Pacis these two scenes are actually at right angle with each other. Professor says “One of the things that is being implied is continuity.” It goes to speak to the most important message of the Ari Pacis, and that is to link the Rome of Augustus to that of the Rome of the past and here it is shown through the continuity of religious observance of both Augustus and Aeneas. 21.5 Here we see Augustus on the throne taking the familiar positioning of Jupiter. This is the same positioning we had seen earlier in the course on an Alexander coin with Zeus on the throne. The god most natural to affiliate Augustus is Jupiter, b/c of their similar position over their respective kingdoms. Horace once wrote “Jupiter reigns on high, Augustus Reigns on earth.” 22.1 This is a Turquoise cameo of Livia and Tiberius. 14-19 AD. in the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. I could not find it in the lecture it was supposedly presented in. 23.2 This is a portrait of Livia. It is presented in the lecture where the prof. talks about the emphasis put on the fertility of Augustus’ family. In doing so they must be careful showcase Livia without emphasizing her traditional role. This is what the image her is doing. Otherwise it may be unsettling for Romans to see a woman showcased b/c they fear the behind the scenes power of the woman. 23.3 This is a possible image of Julia. Though, it has not been clearly identified as Julia. It is from a Villa owned by her youngest son Agrippa Posthumous. The prof does not say much else about this image. 23.5 This is the bust of Antonia the Younger, the daughter of Marc Antony and Livia. She became the mother, grandmother, and great grandmother of future emperors by Drussus the brother of Tiberius. In contrast to the portrayals of Julia, Antonia is looked up on as the ideal roman wife. This slide is not mentioned in the lecture though. 24.1 This is an image of Napolean of the revolution. It is presented in a lecture where the prof is showing the influence of Augustus on the rest of history. His first title is significant. It was consul. The prof references that both the French and the American revolutions were influenced by contemplating Roman history dealing with the Republic. 24.2 Be careful here. The slide shown as a thumbnail is actually not the same as the one that pops up when you click on it. The thumbnail is oh the Arch of Constantine. This landscape is important b/c at this time Mussolini wanted this type of open space for the parades of his forces. The image that pops up is the Proposal for Die Halle der Partei with attached mausoleum for Hitler. He wanted his mausoleum to be connected to the Hall of the Fascist Party. Hitler was fascinated with architecture and rebuilding of landscapes as was Augustus. This is the only real link we can draw between the two figures. 24.10 Here is an image of propaganda used by Mussolini. He covered himself in the imagery of ancient Rome, like in this picture, the SPQR, the fasces, the wolf, and Latin terms. This is to recall the greatness of his people and feed form that.