Job satisfaction may be a condition for high performance

advertisement

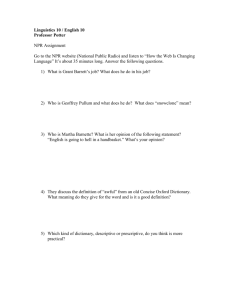

FEDERAL AGENCIES IN TRANSITION: ASSESSING THE IMPACT ON FEDERAL EMPLOYEE JOB SATISFACTION AND PERFORMANCE Gene A. Brewer The University of Georgia School of Public and International Affairs Department of Public Administration and Policy 204 Baldwin Hall Athens, GA (USA) 30602.1615 Telephone: +1.706.542.9660 FAX: +1.706.583.0610 Email: cmsbrew@uga.edu Soo-Young Lee The University of Georgia Email: soo3121@uga.edu Prepared for delivery at the 8th Public Management Research Conference, School of Policy, Planning and Development, University of Southern California – Los Angeles, September 29 – October 1, 2005. 1 FEDERAL AGENCIES IN TRANSITION: ASSESSING THE IMPACT ON FEDERAL EMPLOYEE JOB SATISFACTION AND PERFORMANCE Abstract This study assesses the National Performance Review (NPR) and revisits the longrunning debate about the relationship between job satisfaction and performance. Metaanalyses have found that this latter relationship is weak, but public agencies are underrepresented in these studies. We posit that the relationship between satisfaction and performance is actually much stronger in public agencies, especially when job satisfaction is broadly defined and organizational performance – rather than individual performance – is the outcome of interest. We specify several additional hypotheses about the factors that affect job satisfaction, the impact of the NPR, and the effects on employee job turnover. To test these hypotheses, we compile a pooled, cross-sectional data set consisting of the 1989, 1992, 1996, and 2000 Merit Principles Surveys (N = 46,038) collected by the U.S. Merit Systems Protection Board. The results show that job satisfaction declined in the Federal service during the period 1992–2000, and that this decline dampened what would have been a sharp increase in Federal agency performance. Ironically, the Clinton Administration’s NPR is both villain and hero, weakening job satisfaction and employee commitment to stay in the Federal service, but also strengthening organizational performance over time. Thus, these results confirm that satisfaction plays a strong, seminal role in the overall sustained performance of public agencies, and it also increases their ability to retain employees. These findings raise important implications for public management theory and practice. FEDERAL AGENCIES IN TRANSITION: ASSESSING THE IMPACT ON FEDERAL EMPLOYEE JOB SATISFACTION AND PERFORMANCE Introduction Over the past 25 years, Federal agencies have undergone a period of radical – almost surreal – change. These agencies have been transitioning from traditional civil service systems to more nimble, performance-oriented systems; from a client focus to a new customer service orientation; and from status as a “monopoly provider” to that of “contract manager,” overseeing a vast implementation network that consists of other federal, state, and local agencies, nonprofit organizations, private sector firms, and other interested parties. This period of rapid change is well-documented and has been the subject of numerous qualitative assessments and empirical analyses from the public management community (for example, see Kettl and DiIulio, 1995; Ingraham et al., 1997). Ironically, what is missing from this important stream of scholarly inquiry is good empirical work that takes into account the across-time dimension of the problem and focuses on the implications for government performance (Boyne, 2003). Accordingly, this study will create a pooled cross-sectional data set from existing data sources and explore the research questions described below – principally, how have the tides of reform affected Federal employee job satisfaction and performance, the tenuous relationship between these constructs, and employee intentions to remain in the Federal service? Federal employee job satisfaction, whether measured directly or in conjunction with other measures of satisfaction, seems to be declining over time (U.S. MSPB, 2000; Light, 2002). But what of it? Conventional wisdom suggests that job satisfaction is an important barometer in work organizations, but previous research indicates that it is not strongly related to job performance. Yet, job satisfaction may be related to other factors that affect performance, and it may be related to the overall sustained success of the organization (for rationales, see Rucci, Kirn & Quinn, 1998; U.S. MSPB, 2001; Kim, 2005). In addition, both job satisfaction and performance are multi-dimensional constructs, and some of their sub-dimensions may be more strongly related than the parent constructs (Boyne, 2003; Rainey, 2003). Such alternative specifications of the satisfaction-performance linkage seem particularly plausible in the public sector. To study this set of research questions, a pooled cross-sectional data set is created from existing Merit Principles Survey data sets compiled by the U.S. Merit Systems Protection Board. These data sets span a 12-year-period and include the following: 1989, N = 15,939; 1992, N = 13,432, 1996, N = 9,710; and 2000, N = 6,957. The resulting data set permits a careful investigation of Federal agency change during the NPR and its impact on Federal employee job satisfaction, performance, and intent to remain in the Federal service over time. Thus, this study builds on and extends a rich tradition of scholarship on Federal agency reforms and their effects on the Federal workforce. The National Performance Review and “Reinventing Government” Federal management reform efforts over the past twelve years have gone through three stages (Kamensky, 2003): The National Performance Review (NPR I, 1993-1997); The National Partnership for Reinventing Government (NPR II, 1997-2000); and The President’s Management Agenda (2000-present). These three stages are described in more detail below. The National Performance Review (NPR I, 1993-1997). NPR I was a top-down reform effort designed to cut red tape, increase efficiency, and improve performance. Two developments shifted its focus from the milder reinvention movement to the more ideological and invasive reform agenda that followed: passage of The Government Performance and Results Act of 1993 (P.L. 103-62) and the 1994 mid-term elections, which led to a Republican takeover in Congress. NPR I focused intently on downsizing – eventually cutting 426,000 employees, 250 programs, and 16,000 pages of regulations government-wide. The themes of the reform effort included increasing efficiency, economy, effectiveness, while fairness and equity criteria were often neglected. Even though the Vice President praised public employees in the early days, personnel reductions became the centerpiece of the reform effort. The National Partnership for Reinventing Government (NPR II, 1997-2000). NPR II, roughly corresponding with President Bill Clinton’s second term in office, was a bottom-up reform effort designed to consolidate the changes introduced in the original (and ongoing) NPR I. NPR II sought to benchmark, reengineer work processes, and begin the long-term process of cultural change in Federal agencies. Considerable emphasis was placed on improving “customer service” and restoring public trust in government, which the Vice President claimed was the gold standard of success. The President’s Management Agenda (2000-present). The Bush administration plan is similar to NPR I and II in several ways. It is an OMB-run reform effort with five main priorities: strategic human capital, competitive sourcing, improved financial performance, expanded electronic government, and budget and performance integration. The important point here is that many of the reforms introduced in NPR I and NPR II are still being advanced in the Bush administration – in many cases more boldly and extremely. For example, the assault on Federal employee job satisfaction has intensified and there have been several catastrophic performance failures over the past five years, including the 9/11 terrorist attacks and the more recent hurricane disaster in New Orleans. Policy-makers and public managers need to know how this long-running, somewhat bi-partisan set of reforms has affected the Federal workforce. In the study that follows, the NPR I and NPR II are prominent variables. Through a 12-year window, this study will examine the effects of Federal agency change on Federal employee job satisfaction and performance, the relationship between these constructs, and the effects on job turnover. Specifically, we examine the effects of various reforms (e.g., the Clinton Administration’s National Performance Review or NPR, The Government Performance and Results Act of 1993, etc.) on the levels of job satisfaction and performance, and the linkage between these constructs. The analysis will include several different measures of satisfaction (job, pay, supervisor, etc.) and a robust, multiple-item measure of performance. While the effects of these reforms cannot be isolated and evaluated with absolute certainty, the results are very suggestive. 2 Important Variables: Job Satisfaction, Commitment to Stay, and Organizational Performance Job satisfaction is one of the most-studied concepts in the social and behavioral sciences. The voluminous research literature on the topic has not, however, resolved some of the more important and enduring questions that continue to puzzle researchers and managers in a variety of organizations that include business firms, nonprofit organizations, and government agencies. A full blown review of this literature is beyond the scope of this study, but most theoretical and empirical work has been in business firms, which differ fundamentally from nonprofit organizations and public agencies. There are, however, a growing number of nonprofit and public sector studies. Job satisfaction is defined as “the extent to which people like (satisfaction) or dislike (dissatisfaction) their jobs” (Spector, 1997, p. 2). This definition suggests job satisfaction is a general or global affective reaction that individuals hold about their job. Most scholars recognize that job satisfaction is a global concept comprised of various facets such as employee satisfaction with pay, supervisor, and co-workers (Judge et al. 2001a; Rainey, 2003). One useful stream of research has studied the causes and consequences of job satisfaction, and its interrelationships with other important job-related variables. For example, in their meta-analytic construct validity results, Kinicki et al. (2002) showed that job characteristics, role states, group and organizational characteristics, and leader relations are generally considered to be antecedents of job satisfaction and motivation, while citizenship behaviors, withdrawal cognitions, withdrawal behaviors, and job performance are generally considered to be consequences of job satisfaction. This helps to clarify another long-running controversy in the literature: researchers have sometimes encountered problems in specifying causal paths and determining their true direction. For example, it has been unclear whether job satisfaction contributes to individual performance or visa-versa (Porter and Lawler, cited in Rainey, 2003, p. 276). Meta-analyses are helping to sort some of these issues out. These studies generally find that the relationship between job satisfaction and performance is weak (Iaffaldano and Muchinsky, 1985; Judge et al, 2001b; but see Petty, McGee, and Cavender, 1984). However, private sector studies are over-represented in these metaanalytic samples which tends to obscure the fact that job satisfaction may have a slightly different meaning and greater value in the public sector. Of particular importance is the possibility that job satisfaction is more strongly related to individual and organizational performance.1 Although strongly related to job satisfaction, organizational commitment (OC) is a distinct concept that relates to an employee's desire to remain with an organization out of a sense of loyalty, emotional attachment, and financial need (Meyer, Allen, and Smith, 1993). Organizational commitment can defined as the relative strength of an individual’s identification with and involvement in a particular organization (Porter and Smith, 1970). It can be characterized by at least three related factors: (1) a strong belief in and 1 Job satisfaction may be a condition for high performance – not a determinant of it. This suggests a Maslowian interpretation – employees’ basic safety and security needs (job satisfaction, job security, adequate pay, etc.) must be met before high performance is possible. However, as Rainey (2003, pp. 283284) explains, research on work-related satisfaction does not as yet produce a clear pattern. 3 acceptance of the organization’s goals and values; (2) a willingness to exert considerable effort on behalf of the organization; and (3) a strong desire to maintain membership in the organization (Mowday, Steers, and Porter, 1979). Angle and Perry (1981) identified two subscales: value commitment, which reflects a commitment to support organizational goals, and commitment to stay, which reflects a desire to retain organizational membership. Related to Mowday, Steers, and Porter’s third factor – a strong desire to maintain membership in the organization – and Angle and Perry’s commitment to stay, this study also focuses on Federal employees’ commitment to stay in the Federal government service. Empirical results support the importance of affective commitment2 in public organizations (Liou and Nyhan, 1994; Romzek, 1989; 1990), but few studies have specifically focused on Federal employees’ commitment to stay in Federal jobs. Organizational performance is a socially constructed phenomenon that is subjective, complex, and particularly hard to measure in the public sector (Au, 1996; Anspach, 1991). A review of the literature on organizational performance in the public sector reveals several theoretical studies that strive for comprehensiveness (Rainey and Steinbauer, 1999; Wolf, 1993; and others). Some studies emphasize the importance of performance generally (Cohen, 1993; Kettl et al., 1996; Hedley, 1998), while others focus on performance measurement and monitoring (for example, Hatry and Wholey, 1992; Hatry, 1999; Kopczynski and Lombardo, 1999). Some studies are more like best practices research (e.g., Osborne and Gaebler, 1992; Popovich, 1998). An increasing number of studies are trying to define and measure organizational performance in the public sector. For example, Brewer and Selden (2000) and Brewer (2005) operationalized organizational performance using the theoretical dimensions of internal and external efficiency, effectiveness, and fairness. Chun and Rainey (2005) introduced four dimensions of organizational performance: managerial effectiveness, customer service orientation, productivity, and work quality. Andrews, Boyne, Meier, O'Toole, and Walker (2005) suggest two measures of organizational performance – customer satisfaction and a composite indicator that covers a range of service outputs and outcomes. Customer satisfaction measures the percentage of citizens satisfied with the overall service provided by their authority, and the composite indicator covers six dimensions of performance – quantity of outputs, quality of outputs, efficiency, outcomes, value for money, and consumer satisfaction with individual services. While all of these approaches have merits, this study will use Brewer and Selden’s (2000) and Brewer’s (2005) approach to defining and measuring organizational performance. The relationship between job satisfaction and performance is somewhat controversial, as mentioned above. We posit that job satisfaction is more prominent and important in the public sector, and is more strongly linked to organizational performance, for several reasons. First, previous studies have shown that the link between job satisfaction and individual performance is higher among white collar workers in more complex jobs. The public sector is heavily populated with these workers and jobs. Second, studies have shown that positive mood – including job satisfaction – is linked with altruistic motives and prosocial behavior, such as public service motivation, 2 Affective commitment refers to the employee’s emotional attachment to, identification with, and involvement in the organization (Meyer and Allen, 1991). 4 organizational citizenship behavior, etc. (Brewer, 2001; Organ, 1977). These behaviors are central to public service (Brewer, 2003; Houston, forthcoming). Third, research on the determinants of satisfaction suggests that it may be sensitive to issues such as participation (+), bureaucrat bashing (-), and reforms (mixed), all of which are prominent issues in the contemporary public sector environment. Job satisfaction is positively correlated with organizational commitment, job involvement, motivation, organizational citizenship behavior, life satisfaction, mental health, and job performance. It is negatively related to turnover, absenteeism, and perceived stress (Judge et al. 2001a; Kreitner and Kinicki, 2001; Spector, 1997). Thus, this study assumes that job satisfaction and commitment to stay are positively related to each other. On the relationship between commitment to stay and organizational performance, research has found that highly committed employees may perform better than less committed ones (Mowday, Porter, and Dubin, 1974). Larson and Fukami (1984) also found that higher levels of organizational commitment are linked to higher levels of job performance. Especially, affective commitment correlated positively with the performance of lower-level managers in a large food service company (Meyer et al., 1989). Therefore, we assume that federal employee’s commitment to stay is positively related with organizational performance. Overall, the U.S. Merit Systems Protection Board (2003) and other reliable sources suggest that Federal employees’ job satisfaction and commitment to stay in the Federal service have declined over the past twelve years, and that this decline has dampened Federal agency performance (for example, see pp. 11-15). We believe the corrosive effects of the NPR and the related neglect of policy-makers and public managers are the primary reasons. Data and Methods The research questions raised in the previous section are translated into models and tested using data from the U.S. Merit Systems Protection Board’s (MSPB) Merit Principles Surveys. The agency conducts these surveys every three or four years to keep policy makers apprised of Federal employees’ attitudes and behavior on matters of current interest. To study this set of research questions, especially the influence of NPR I and NPR II, we compile a pooled, cross-sectional data set consisting of the 1989, 1992, 1996, and 2000 Merit Principles Surveys (N = 46,038). According to Wooldridge (2003), many surveys of firms, families, and individuals are repeated at regular intervals. If a random sample is drawn at each time period, pooling the resulting random sample gives us an independently pooled cross section. We can thus study how relationships change over time by including dummy variables, in this case for 1996 and 2000. For this part of the statistical analysis, we use a pooled cross-sectional data set consisting of 1992, 1996, and 2000 Merit Principles Surveys (N = 30,099),3 dropping the 3 These three surveys have uneven sample size (the 1992 sample is unusually large). Thus, we were concerned about bias in the pooled data set. To test for such bias, we randomly drew 6,957 cases from each survey data set, ran the same models, and compared them with the models reported herein. The results were very similar – all variables and coefficients ran in the same direction and achieved the same significance levels (t-scores were slightly different, of course). We then repeated this procedure and obtained the same result. Based on this result, we conclude that there is no bias due to uneven sample size. 5 1989 survey because it did not provide measurement items for several important constructs that were needed to test our models. The 1992 survey data set involved a sample of 20,851 full-time executive branch employees in the federal government. Approximately 64 percent, or 13,432 employees, returned completed questionnaires. The 1996 survey included a random sample of 18,163 permanent full-time employees in the federal agencies. In all, 9,710 persons completed and returned surveys for a response rate of approximately 53.5 percent. The 2000 survey data set involved a random sample of 17,250 full-time permanent employees in the federal executive branch agencies. The response rate was 43 percent, that is, 6,957 employees returned completed questionnaires. We scrutinized 1992, 1996, and 2000 Merit Principles Surveys and abstracted common items from them. The Appendix describes how these items are used to operationalize different constructs, and reports means and standard deviations for each. Organizational performance – the dependent variable in our main model – is measured with six survey items that tap different dimensions of the construct. These dimensions come from Brewer and Selden’s (2000, 688-89) and Brewer’s (2005) 2 × 3 typology of organizational performance consisting of internal and external dimensions, each of which focused on the core administrative values of efficiency, effectiveness, and fairness. We included three items related to fairness because we felt that the NPR focused on efficiency, economy, and effectiveness (via invasive reforms such as downsizing, personnel reductions, agency reorganizations, etc.), while fairness and equity criteria were often neglected. Past research on organizational performance has neglected fairness and equity concerns, but past experience shows that these concerns are crucial in the public sector (Frederickson, 1990; Selden, Brewer, and Brudney, 1999; Brewer and Selden, 2000; Brewer, 2005). The resulting index taps most dimensions of the construct, and it yields an Alpha reliability coefficient of .72.4 The first item, quality of coworkers and their work, and the third item, quality of incoming employees, are scaled from 1, poor, to 5, outstanding. The second item is based on a scale ranging from 1, strongly disagree, to 5, strongly agree. The last three items – fair promotions, awards and training – use a five-point-scale that ranges from 1, to no extent, to 5, to a very great extent. These items provide a broad assessment of perceived organizational performance. Although this perceptual measure of organizational performance has some limitations such as possible measurement error, the potential for monomethod bias, and availability, there is some precedent for using it (Bollar, 1996; Brewer, 2005; Brewer and Selden, 2000; Brewer, 2005; Delaney and Huselid, 1996; Jennings and Ewalt, 1998; Parhizgari and Gilbert, 2004; Youndt et al., 1996). Studies have shown that measures of perceived organizational performance correlate positively (with moderate to strong associations) with objective measures of organizational performance (Delaney and Huselid, 1996; Dollinger and Golden, 1992; McCracken, McIlwain, and Fottler, 2001; Pearce, Robbins, and Robinson, 1987; Powell, 1992). Walker and Boyne cite a range of evidence that demonstrates “there are positive and statistically significant correlations between objective and subjective measures of overall performance, some in the region of r = .8” (2004, 16). The variables “job satisfaction” and “commitment to stay” are of particular interest in this study. They appear as both independent and dependent variables in our models. Thus, we assess Federal employees’ job satisfaction, pay satisfaction, and satisfaction 4 All of the indexes used in this study were created by adding the measurement items that composed them. 6 with their supervisor using survey items that ask employees to rate questions such as “In general I am satisfied with my job,” “Overall, I am satisfied with my current pay,” and “Overall, I am satisfied with my supervisor.” The responses range from 1, strongly disagree, to 5, strongly agree. We also incorporate a measure of “commitment to stay.” The following survey question taps this item: “Do you plan to look for another job outside the Federal government in the coming year?” This question measures employees’ intent to leave the Federal government. We reversed the responses to obtain a measure of employees’ commitment to stay in the Federal government. The reversed response categories are yes for staying and no for leaving. “NPR I” and “NPR II” are also of particular interest in our models. They are dummy variables which represent the 1996 and 2000 MSPB surveys, respectively, and the NPR reforms described earlier. We assume that NPR I and NPR II have different influences on federal employees’ job satisfaction, commitment to stay, and organizational performance. That is, we believe that NPR I had a more negative impact than NPR II because it was more invasive and severe. Therefore, we investigate the impact of NPR I (1993 - 1997) on job satisfaction, commitment to stay, and organizational performance between the 1992 and 1996 surveys using the dummy variable “NPR I,” and the impact of NPR-2 (1997 - 2000) on job satisfaction, commitment to stay, and organizational performance between 1996 and 2000 surveys using the variable “NPR II.”5 Our measure of “meaningfulness of work” is a question asking respondents if the work they do (on their jobs) is meaningful to them. This item can be related to task motivation and even to Public Service Motivation because this MSPB survey is focusing on public employees. The related concept of “recommend government employment” is measured with the following question: “I would recommend the Federal Government or Government as a place to work.” We measured “cooperation & teamwork” with a question asking Federal employees if a spirit of cooperation and teamwork exists in their work unit. We believe this reflects an organization’s internal climate or culture. We assess “sufficient training” by tapping a question that asks respondents whether they have received the training they need to keep pace with and perform the requirements of their jobs. The responses for these items range from 1, strongly disagree, to 5, strongly agree. To measure “retaliation,” respondents were asked if they have been retaliated against or threatened with retaliation in the past two years for any of the following: making disclosures concerning health and safety dangers, unlawful behavior, and/or fraud, waste, and abuse; exercising any appeal, complaint, or grievance right; testifying for or otherwise assisting any individual in the exercise of whistle-blowing, equal opportunity, or appeal rights, or refusing to obey an unlawful order. ‘Yes’ responses to these items were summed. The Cronbach’s alpha for this variable is a pleasing .97. 5 We included two dummy variables because there are three survey years (1992, 1996, and 2000) in our pooled data set. The base group for comparison is the 1992 survey. Therefore, NPR-1 indicates the difference between 1992 and 1996 and NPR-2 shows the difference between 1992 and 2000. Strictly speaking, in NPR-2’s case, the variable does not tell us the difference between 1996 and 2000. The coefficient of difference between 1996 and 2000 can be calculated subtracting NPR-1’s coefficient from NPR-2’s coefficient (Wooldridge 2003; 228). To test the significance of this coefficient, we estimated another model which included the 1996 survey as the base group for the 1992 and 2000 dummy variables. Using this model, we tested the coefficient of the difference between the 1996 and 2000 surveys and found that it was both positive and statistically significant. 7 Finally, we include five demographic variables such as age, education, gender, supervisory status, and work experience as control variables because they may influence job satisfaction, commitment to stay, and organizational performance. We also tried to include a minority status variable to capture diversity, but this variable was dropped from the final equations because it was a weak and insignificant predictor. Next, we report our findings on ordinary least squares (OLS) regression equations predicting job satisfaction and organizational performance and a logit model predicting commitment to stay. Findings In this section, the NPR and other independent variables are tested in multivariate models constructed from the overlapping literatures on job satisfaction, commitment to stay, and organizational performance. As a preliminary step, Table 1 shows the respondents’ background characteristics – their age, education, gender, supervisory status, and work experience – on the three surveys. The demographic characteristics of the three groups are very similar. [insert Table 1 about here] Table 2 reports the results of the OLS multiple-regression analysis predicting job satisfaction of Federal employees.6 The adjusted multiple coefficient of determination is .50, meaning that the independent variables together account for 50 percent of the variation in federal employees’ perceptions of job satisfaction. The results are highly significant, providing confidence at the .001 level.7 [insert Table 2 about here] The individual factors affecting Federal employees’ job satisfaction are discussed next. Examination of the standardized coefficients reveals that “meaningfulness of work” (.38) exerts the strongest influence on job satisfaction, followed by “recommend government employment” (.18). This result may reflect that the fact that the sample is comprised of public employees. Surprisingly, “satisfaction with supervisor” (.16) exerts more influence on job satisfaction than “pay satisfaction” (.14). Higher levels of education have a negative impact on job satisfaction, and women seem to be associated with lower levels of job satisfaction than men. The “NPR I” variable tells us that Federal employees’ job satisfaction in 1996 is lower than that of 1992, and the “NPR II” variable shows that Federal employee’s job satisfaction in 2000 is lower than that of 1992. These two NPR variables indicate that both the first and second NPR reforms, compared with the 1992 baseline survey, produced a negative impact on Federal employee’s job satisfaction. In addition, the first NPR’s magnitude of negative influence is somewhat greater than that of the second NPR. In this case, as we mentioned above, we cannot tell the difference between the 1996 and 2000 surveys because both NPR I and NPR II are compared with the 1992 survey. Therefore, to estimate the pure impact of the second NPR on job satisfaction (between Responses such as ‘don’t know’ or ‘no basis to judge’ were excluded from the analysis. A correlation matrix showed no evidence of problematic multicollinearity among independent variables, but the variance inflation index for retribution was moderately high. This will be investigated further. 6 7 8 1996 and 2000), we ran a model which includes the 1996 survey as the base group. Using this model, we found that the second NPR has a positive influence on job satisfaction and it is statistically significant.8 This result is consistent with our expectation. In sum, the first NPR, compared with the 1992 survey, has a negative impact on job satisfaction while the second NPR, compared with the 1996 survey, has a positive influence on job satisfaction. Table 3 presents the estimated coefficients and significance levels for a maximum likelihood logistic regression model predicting Federal employees’ commitment to stay in their Federal jobs. Four pseudo R2s range from .16 - .27 – which suggests a modest explanation.9 The equation indicates that all the variables have a significant effect on federal employee’s commitment to stay, all attaining statistical significance at the .01 level or more. All variables except age, supervisory status, NPR I, and NPR II have a positive influence on Federal employees’ commitment to stay. Importantly, all three satisfaction variables – i.e., job satisfaction, pay satisfaction, and satisfaction with supervisor – show a positive and significant impact on Federal employees’ commitment to stay. [insert Table 3 about here] Both NPR I and NPR II have significant and negative effects on Federal employees’ commitment to stay. As mentioned above, to check the pure influence of NPR II between 1996 and 2000, we ran another model using the same method described above. The results show that the second NPR has a positive and significant impact on Federal employees’ commitment to stay.10 This result is also consistent with our expectation. In sum, the first NPR, compared with the 1992 baseline survey, has a negative effect on Federal employees’ commitment to stay while the second NPR, compared with 1996 survey, has a positive influence on Federal employees’ commitment to stay. Table 4 reports the results of the OLS multiple-regression analysis predicting organizational performance in Federal employees. The adjusted multiple coefficient of determination is .50, meaning that the independent variables together account for approximately half of the variation in organizational performance. The equation achieves statistical significance at the .001 level.11 All coefficients show significance at the .001 level as well. [Table 4 about here] Next, we examine the standardized coefficients to judge the relative importance of each factor that affects organizational performance. Examination of the standardized coefficients reveals that “satisfaction with supervisor” (.24) has the strongest influence on 8 In this case, the coefficient is .03 and it is statistically significant at the .05 level of confidence. There is no statistic in logit analysis comparable to the R2 value in regression. A number of pseudo R2 measures have been proposed. However, the pseudo R2 value is neither universally accepted nor universally reported (Brewer and Selden, 1998). 10 In this case, the coefficient is .43 and is significant at the level of .001. 11 A correlation matrix and variance inflation indexes showed no evidence of problematic multicollinearity among independent variables. 9 9 organizational performance, followed by “cooperation and teamwork” (.20). Satisfaction with supervisor is the most influential factor, compared with job satisfaction and pay satisfaction. The relationship between job satisfaction and organizational performance is still controversial (Kim, 2005), although these results provide some clarification. In this analysis, we find that “job satisfaction” (.16) alone has a positive, significant, and considerable effect on organizational performance. “Commitment to stay” (.03) shows the weakest positive influence on organizational performance. Unlike the job satisfaction model, “meaningfulness of work” (.08) and “recommend government employment” (.04) do not have large effects. Among the demographic variables, age (-.05) and work experience (-.04) have negative and significant effects on organizational performance. The NPR I (-.616) variable tells us that reforms lowered organizational performance in 1996 relative to the 1992 survey, and the NPR II (.70) variable shows that organizational performance in 2000 is higher compared with the 1992 survey. These two NPR variables indicate that, compared with the 1992 survey, the first NPR reforms had a negative impact on organizational performance while the second NPR had a positive effect. We again use the method described above to obtain a pure estimate of the NPR II’s influence – i.e., we re-estimate the model comparing the 1996 survey with the 2000 survey. The result shows that the second NPR has a positive and significant impact on organizational performance.12 This result is also consistent with our expectation. In sum, the first NPR, compared with the 1992 survey, has a negative effect on 1996 organizational performance while the second NPR, compared with the 1996 survey, has a positive influence on 2000 organizational performance. Conclusion There have been six major reforms of the Federal bureaucracy in the past century: the Brownlow Commission, the first and second Hoover Commissions, the Ash Council, the Grace Commission, and the National Performance Review (Shafritz and Russell, 2003). This study has focused on how the tides of reform, especially the National Performance Review, have affected Federal employee job satisfaction and performance, the relationship between these constructs, and commitment to remain in the Federal service. We found that the first NPR had a negative effect on job satisfaction, commitment to stay, and organizational performance, while the second NPR had a positive effect on job satisfaction, commitment to stay, and organizational performance. One important implication is that the NPR appears to have improved organizational performance overall. However, the effect was muted by the NPR I and lack of attention to Federal employee job satisfaction and commitment to stay in the Federal service. If the patently negative NPR I had been more positively-oriented like NPR II, Federal agency performance would have increased more sharply, ceteris paribus. In addition, if both NPRs had more carefully attended to Federal employee job satisfaction and commitment, performance would have ratcheted up even higher. Because of these results, we believe this study makes several other noteworthy contributions to the literature on public administration and public management. First, we have created a pooled cross-sectional data set from four existing Merit Principles Survey data sets to study the effects of national-level reforms on Federal employee job satisfaction, commitment to stay, and organizational performance. Studies on the 12 In this case, the coefficient is 1.32 and it is statistically significant at the .001 level. 10 relationship between job satisfaction and organizational performance have shown this relationship to be weak. We hypothesized that the relationship would be stronger in the public sector and the results support this view. Job satisfaction has a positive, significant, and considerable effect on organizational performance. Third, several studies (Kellough and Osuna, 1995; Lewis, 1991; Lewis and Park, 1989; Selden and Moynihan, 2000) have focused on voluntary turnover in Federal and state government, but these studies have not focused on public employees’ commitment and intention to stay in the Federal service. This study provides some evidence on the factors that influence Federal employees’ commitment to stay, and also shows that such commitment is related to organizational performance – an important finding. Several limitations of this study are noted next. First, our measure of organizational performance may be viewed as incomplete because we are using an existing MSPB data set that was not intended to measure or model organizational performance. Certainly, better measures could be devised. Second, we use perceptual measures of organizational performance because the MSPB data do not provide more objective measures, and such measures are not available elsewhere for the time period of interest. Ideally, future research should include both subjective and more objective measures of organizational performance, and continue to examine the relationship between them. Thirdly, we acknowledge that we cannot make causal attributions with this research design. Future research should continue to build evidence and try to cement these important causal relationships. NPR also affected Federal agencies differently, and these effects (which are accompanied by differing levels of staff reductions, funding, etc.) can be more clearly specified and tested by going outside the MSPB data sets. In fact, it may be possible to cobble together data from several sources to mount such a study. This is another challenge for future research. Most policy-makers and public managers would doubtless agree that employee job satisfaction and commitment to stay in the public service are important goals of public management. Most would probably also agree that attaining these goals is linked to organizational performance and effectiveness in Federal agencies. However, in the hurry and strife of reform, these important relationships have been neglected. The overly harsh nature of some reforms has tended to trump efforts to humanize the workforce and capitalize on its considerable talent and devotion to the public service. In fact, these reforms may have seriously eroded the public service and undermined the public service ethic. This study shows that policy-makers and public managers can reverse these effects – and improve Federal agency performance – by nurturing Federal employees’ job satisfaction and commitment to stay in the Federal service. This appears to be a win-win situation. 11 Table 1 Background of Respondents Demographic Variables Frequency (Percent)13 1992 1996 2000 Characteristics Age Under 20 20-29 30-39 40-49 50-54 55-59 60-64 65 and older Education Gender Supervisory status Work experience 13 6 (0) 1171 3149 5007 1904 1233 577 201 (8.7) (23.4) (37.3) (14.2) (9.2) (4.3) (1.5) 0 (0) 1 (0) 402 1761 4015 1852 985 416 151 (4.1) (18.1) (41.3) (19.1) (10.1) (4.3) (1.6) 200 1251 2374 1665 842 387 127 (2.9) (18.0) (34.1) (23.9) (12.1) (5.6) (1.8) 91 (0.7) 102 (1.1) 31 (0.4) 1280 (9.5) 833 (8.6) 488 (7.0) 3745 (27.9) 2652 (27.3) 1661 (23.9) 1241 (9.2) 2783 (20.7) 996 (10.3) 1836 (18.9) 688 (9.9) 1533 (22.0) 1484 (11.0) 1052 (10.8) 750 (10.8) 2575 (19.2) 2002 (20.6) 1622 (23.3) 7754 (57.7) 5366 (39.9) 5870 (60.5) 3569 (36.8) 3860 (55.5) 2989 (43.0) 9813 (73.1) 4719 (48.6) 4912 (70.6) Supervisor Less than 1 yr 3619 (26.9) 3845 (39.6) 1541 (22.2) 102 (0.8) 10 (0.1) 1-5 yrs 6-10 yrs 11-15 yrs 16-20 yrs 21-25 yrs 26-30 yrs 31 yrs and above 2463 2197 2261 2418 1793 1325 719 Less than HS HS diploma HS diploma/some college/technical school 2 yr college degree 4 yr college degree Some graduate/professional school Graduate/professional degree Male Female Non-supervisor (18.3) (16.4) (16.8) (18.0) (13.3) (9.9) (5.4) 879 1634 1574 1913 1831 1163 606 (9.1) (16.8) (16.2) (19.7) (18.9) (12.0) (6.2) 7 (0.1) 604 1003 1364 1078 1178 1002 632 (8.7) (14.4) (19.6) (15.5) (16.9) (14.4) (9.1) The sum of the frequencies may not be the same as sample size because of missing values. 12 Table 2 Predicting Job Satisfaction Variables Age Education Gender Supervisory Status Work Experience Pay Satisfaction Satisfaction with Supervisor Commitment to Stay Recommend Government Employment Meaningfulness of Work Cooperation & Teamwork Sufficient Training Retaliations NPR I NPR II Constant Unstandardized Coefficient .01* -.01*** -.06*** .02* .00 .11*** .13*** .29*** .15*** .42*** .08*** .09*** -.04*** -.17*** -.14*** -.07 Standard Standardized Error Coefficient .01 .01 .00 -.02 .01 -.03 .01 .01 .00 .00 .00 .14 .01 .16 .01 .11 .01 .18 .01 .38 .01 .10 .01 .10 .01 -.08 .03 -.08 .03 -.06 .05 R2 = .50 Adjusted R2 = .50 F value = 1387.71*** N = 21,068 *p = .05; **p = .01; ***p = .001 13 Table 3 Logit Model for Commitment to Stay Variables Age Education Gender Supervisory Status Work Experience Job Satisfaction Pay Satisfaction Satisfaction with Supervisor Meaningfulness of Work Cooperation & Teamwork Sufficient Training NPR I NPR II B .16*** -.21*** .21*** -.21*** .15*** .54*** .19*** .13*** .07** .07*** .05** -1.13*** -.70*** Standard Error (.02) (.01) (.04) (.05) (.01) (.02) (.02) (.02) (.02) (.02) (.02) (.05) (.05) Log likelihood -9115.42 Model chi-squared 3467.81*** Correctly Predicted 84% Pseudo R2 (four measures .16 - .27 N = 24,324 *p = .05; **p = .01; ***p = .001 14 Table 4 Predicting Organizational Performance Variables Age Education Gender Supervisory Status Work Experience Job Satisfaction Pay Satisfaction Satisfaction with Supervisor Commitment to Stay Recommend Government Employment Meaningfulness of Work Cooperation & Teamwork Sufficient Training NPR I NPR II Constant Unstandardized Standard Standardized Coefficient Error Coefficient -.19*** .03 -.05 .24*** .02 .09 .60*** .06 .07 .81*** .06 .08 -.09*** .02 -.04 .69*** .04 .16 .55*** .02 .15 .86*** .03 .24 .30*** .08 .03 .17*** .03 .04 .41*** .04 .08 .77*** .03 .20 .74*** .03 .18 -.62*** .07 -.06 .70*** .07 .07 3.76*** .03 R2 = .50 Adjusted R2 = .50 F value = 914.68*** N = 13,661 *p = .05; **p = .01; ***p = .001 15 Appendix Constructs, Measurement Items, Means, and Standard Deviations Organizational Performance (mean, sd, alpha score) Quality of coworkers and their work - three slightly different questions asking respondents to rate the quality of their current coworkers in their immediate work group (1992), the work performance by their current coworkers in their immediate work group (1996), and the quality of work performed by their work unit as a whole (2000). Responses range from 1 = poor to 5 = outstanding. Utilizing employees’ knowledge, skills, and abilities to become more efficient – two slightly different questions asking respondents to rate how well their organizations use their skills and abilities (1992, 2000) and their knowledge and skills (1996) for this purpose. Responses range from 1 = strongly disagree to 5 = strongly agree. Quality of incoming employees – two slightly different questions asking respondents to rate the quality of people coming into their work group from outside the government (1992) and the quality of work performed by people coming into their work group/unit from outside the government (1996, 2000). Fair promotions – question asking respondents to what extend they believe they have been treated fairly regarding promotions. Fair awards - question asking respondents to what extend they believe they have been treated fairly regarding awards. Fair training - question asking respondents to what extend they believe they have been treated fairly regarding training. Age – respondents are asked “what is your age?” Responses are one of the following: under 20, 20-29, 30-39, 40-49, 50-54, 55-59, 60-64, or 65 or older. Education – respondents were asked “what is your highest educational level?” Responses are one of the following: less than high school diploma, high school diploma or GED, high school diploma or GED plus some college or technical school, 2-year college degree (AA, AS), 4-year college degree (BA, BS, or other bachelor’s degree), or some graduate or professional school, graduate or professional degree. Gender – dummy variable for male or female. Responses coded 0 = male and 1 = female. Supervisory Status – dummy variable indicating whether the employee is a supervisor. Responses coded 0 = non-supervisor and 1 = supervisor. Work Experience – respondents were asked how many years they have been a Federal Government employee (excluding military service)? Responses are one of the following: less than 1 year, 1-5 years, 6-10 years, 11-15 years, 16-20 years, 21-25 years, 26-30 years, or 31 years or more. Job Satisfaction – respondents were asked to rate the following question: “In general I am satisfied with my job.” Responses range from 1 = strongly disagree to 5 = strongly agree. 16 Pay Satisfaction – respondents were asked to rate the following question: “Overall, I am satisfied with my current pay.” Responses range from 1 = strongly disagree to 5 = strongly agree. Satisfied with Supervisor – respondents were asked to rate the following question: “Overall, I am satisfied with my supervisor.” Responses range from 1 = strongly disagree to 5 = strongly agree. Commitment to Stay – two slightly different questions asking respondents if they plan to look for another job outside the Federal government in the coming year (1992, 1996, 2000). Responses range from 0 = no to 1 = yes (item reversed). Recommend Government Employment – two slightly different questions asking respondents whether they would recommend the Federal Government as a place to work (1992, 1996), or whether they would recommend the Government as a place to work (2000). Responses range from 1 = strongly disagree to 5 = strongly agree. Meaningfulness of Work – two slightly different questions asking respondents if the work they do on their jobs is meaningful to them (1992, 1996), or if the work they do is meaningful to them (2000). Responses range from 1 = strongly disagree to 5 = strongly agree. Cooperation and Teamwork – respondents were asked if a spirit or cooperation and teamwork exists in their work unit. Responses range from 1 = strongly disagree to 5 = strongly agree. Sufficient Training – two slightly different questions asking respondents whether they have received the training they need to keep pace with the requirements of their jobs as these have changed (1992, 1996), or whether they receive the training they need to perform their jobs (2000). Responses range from 1 = strongly disagree to 5 = strongly agree. Retaliation – respondents were asked if they have been retaliated against or threatened with retaliation in the past two years for any of the following: making disclosures concerning health and safety dangers, unlawful behavior, and/or fraud, waste, and abuse; exercising any appeal, complaint, or grievance right; testifying for or otherwise assisting any individual in the exercise of whistle blowing, equal opportunity, or appeal rights, or refusing to obey an unlawful order. “Yes” responses to these items were summed. NPR I – dummy variable for the 1996 survey. NPR II – dummy variable for the 2000 survey. 17 References Andrews, R., G.A. Boyne, K. J. Meier, L. J. O'Toole, Jr., and R. M. Walker, 2005. “Representative Bureaucracy, Organizational Strategy, and Public Service Performance: An Empirical Analysis of English Local Government.” Journal of Public Administration Research & Theory, 15, 4: 489-504. Angle, H. L., and J. L. Perry, 1981. “An Empirical Assessment of Organizational Commitment and Organizational Effectiveness.” Administrative Science Quarterly 26: 1–13. Anspach, R.R. 1991. “Everyday Methods for Assessing Organizational Effectiveness.” Social Problems 38: 1-19. Au, C., 1996. “Rethinking Organizational Effectiveness: Theoretical and Methodological Issues in the Study of Organizational Effectiveness for Social Welfare Organizations.” Administration in Social Work 20: 1–21. Bollar, S.L., 1996. The Impact of Organizational Culture on Employee Work Attitudes, Readiness for Change, and Organizational Performance. Ph.D. dissertation, Georgia Institute of Technology. Boyne, G.A., 2003. “Sources of Public Service Improvement: A Critical Review and Research Agenda.” Journal of Public Administration Research & Theory 13, 3: 367-394. Brewer, G.A., 2005. “In the Eye of the Storm: Frontline Supervisors and Federal Agency Performance.” Journal of Public Administration Research & Theory 15, 4: 505527. ______, 2003. “Building Social Capital: Civic Attitudes and Behavior of Public Servants.” Journal of Public Administration Research & Theory 13, 1: 5-26. ______, 2001. A Portrait of Public Servants: Empirical Evidence from Comparisons with Other Citizens. Ph.D. dissertation, The University of Georgia. Brewer, G.A., and S.C. Selden, 1998. “Whistle-blowers in the Federal Civil Service: New Evidence of the Public Service Ethic.” Journal of Public Administration Research & Theory 8, 3: 413-439 ———, 2000. “Why Elephant Gallop: Assessing and Predicting Organizational Performance in Federal Agencies.” Journal of Public Administration Research & Theory 10, 4: 685-711. Chun, Y.H., and H. G. Rainey, 2005. “Goal Ambiguity and Organizational Performance in U.S. Federal Agencies.” Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory, 15, 4: 529-557. Cohen, S., 1993. “Defining and Measuring Effectiveness in Public Management.” Public Productivity and Management Review 17, 1: 53-89. Delaney, J.T., and M.A. Huselid, 1996. “The Impact of Human Resource Management Practices on Perceptions of Organizational Performance.” Academy of Management Journal. 39, 4: 949–969. Dollinger, M.J., and P.A. Golden, 1992. “Interorganizational and Collective Strategies in Small Firms: Environmental Effects and Performance.” Journal of Management. 18, 4: 695-715. Frederickson, H.G., 1990. “Public Administration and Social Equity.” Public Administration Review 50: 228-237. 18 Hatry, H.P., ed., 1999. “Mini-Symposium on Intergovernmental Comparative Performance Data.” Public Administration Review 59, 5: 101–134. Hatry, H.P., and Wholey, J.S. 1992. “The Case for Performance Monitoring.” Public Administration Review 52, 5: 604–610. Hedley, T.P. 1998. “Measuring Public Sector Effectiveness Using Private Sector Methods.” Public Productivity and Management Review 21: 251-258. Houston, David, forthcoming. “’Walking the Walk’ of Public Service Motivation: Public Employees and Charitable Gifts of Time, Blood, and Money.” Journal of Public Administration Research & Theory. Iaffaldano, M.T., and P.M. Muchinsky, 1985. “Job Satisfaction and Job Performance: A Meta-Analysis.” Psychological Bulletin 97, 2: 251-273. Ingraham. P.W., P.G. Joyce, and A.D. Donahue, 2003. Government Performance: Why Management Matters. Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press. Jennings, E.T., and J.A.G. Ewalt. 1998. “Interorganizational Coordination, Administrative Consolidation, and Policy Performance.” Public Administration Review 58, 5: 417–428. Judge, T.A., S. Parker, A.E. Colbert, D. Heller, and R. Ilies. 2001a. “Job satisfaction: A Cross-Cultural Review.” In N. Anderson, D.S. Ones, H.K. Sinangil, and C. Viswesvaran, eds., Handbook of Industrial, Work and Organizational Psychology, Vol. 2, pp. 25–52. London: Sage. Judge, T.A., C.J. Thoreson, J.E. Bono, and G.K. Patton, 2001b. “The Job Satisfaction-Job Performance Relationship: A Qualitative and Quantitative Review.” Psychological Bulletin 127, 3: 376-407. Kellough, J.E. & W. Osuna, 1995. “Cross-Agency Comparisons of Quit Rates in the Federal Service: Another Look at the Evidence.” Review of Public Personnel Administration 15, 4: 58-68. Kettl, D.F., and J.J. DiIulio, 1995. Inside the Reinvention Machine: Appraising Governmental Reform. Washington, DC: Brookings. Kettl, D.F. et al., 1996. Civil Service Reform: Building a Government That works. Washington D.C.: Brookings. Kim, S., 2005. “Individual-Level Factors and Organizational Performance in Government Organizations” Journal of Public Administration Research & Theory 15, 2: 245261. Kinicki, A.J., F.M. McKee-Ryan, C.A. Schriesheim, and K.P. Carson, 2002. “Assessing the Construct Validity of the Job Descriptive Index: A Review and MetaAnalysis.” Journal of Applied Psychology 87, 1: 14-32. Kopczynski, M., and M. Lombardo, 1999. “Comparative Performance Measurement: Insights and Lessons Learned from a Consortium Effort.” Public Administration Review 59, 2: 124–134. Kreitner, R., and A. Kinicki, 2001. Organizational Behavior, 5th ed. Boston, MA: McGraw-Hill. Larson, E.W., and C.V. Fukami, 1984. “Relationships between Worker Behavior and Commitment to the Organization and Union.” Academy of Management Proceedings 34: 222–226. Lewis, G.B., 1991. “Turnover and the Quiet Crisis in the Federal Civil Service.” Public Administration Review 51, 2: 145-155. 19 Lewis, G.B. and K. Park, 1989. “Turnover in Federal White Collar Employment: Are Women More Likely to Quit than Men?” American Review of Public Administration, 18, 1: 13-28. Light, P.C., 2002. The Troubled State of the Federal Public Service. Washington, DC: The Brookings Institution. Liou, K., and R.C. Nyhan, 1994. “Dimensions of Organizational Commitment in the Public Sector: An Empirical Assessment.” Public Administration Quarterly 18: 99–118. McCracken, M.J., T.F. McIlwain, and M.D. Fottler, 2001. “Measuring Organizational Performance in the Hospital Industry: An Exploratory Comparison of Objective and Subjective Methods.” Health Services Management Research 14: 211–219. Meyer, J.P., and N.J. Allen, 1991. “A Three-Component Conceptualization of Organizational Commitment.” Human Resource Management Review 1, 1: 61–89. Meyer, J.P., N.J. Allen, and C.A. Smith, 1993. “Commitment to Organizations and Occupations: Extension and Rest of a Three Component Conceptualization.” Journal of Applied Psychology 78, 4: 538–551. Meyer, J.P., S.V. Paunonen, I.R. Gellatly, R.D. Goffn, and D.N. Jackson, 1989. “Organizational Commitment and Job Performance: It’s the Nature of the Commitment that Counts.” Journal of Applied Psychology 74, 1: 152–56. Mowday, R.T., R.M. Steers, and L.W. Porter, 1979. “The Measurement of Organizational Commitment.” Journal of Vocational Behavior 14, 2: 224–247. Mowday, R.T., L.W. Porter, and R. Dubin., 1974. “Unit Performance, Situational Factors, and Employee Attitudes in Spatially Separated Work Units.” Organizational Behavior and Human Performance 12, 2: 231–248. Organ, D.W., 1977. “A Reappraisal and Reinterpretation of the Satisfaction-CausesPerformance Hypothesis.” Academy of Management Review 2: 46-53. Osborne, D., and T. Gaebler, 1992. Reinventing Government. Reading, MA: AddisonWesley. Parhizgari, A.M., and G.R. Gilbert, 2004. “Measures of Organizational Effectiveness: Private and Public Sector Performance.” Omega: The International Journal of Management Science. 32, 3: 221–29. Pearce, J.A. II, D.K. Robbins, and R.B. Robinson Jr., 1987. “The Impact of Grand Strategy and Planning Formality on Financial Performance.” Strategic Management Journal 8, 2: 125–34. Popovich, M.G., ed., 1998. Creating High-Performance Government Organization. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass. Porter, L.W., and F.J. Smith, 1970. “The Etiology of Organizational Commitment.” Unpublished manuscript, University of California, Irvine. Powell, T.C., 1992. “Organizational Alignment as Competitive Advantage.” Strategic Management Journal. 13, 2: 119–34. Rainey, H.G., 2003. Understanding and Managing Public Organizations, 3d ed. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass. Rainey, H.G., and P. Steinbauer. 1999. “Galloping Elephants: Developing Elements of a Theory of Effective Government Organizations.” Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory 9, 1: 1–32. 20 Romzek, B.S., 1989. “Personal Consequences of Employee Commitment.” Academy of Management Journal 32, 3: 649–61. ———, 1990. “Employee Investment and Commitment: The Ties that Bind.” Public Administration Review 50, 3: 374–82. Rucci, Anthony J., Steven P. Kirn, and Richard T. Quinn, 1998. “The EmployeeCustomer Profit Chain at Sears.” Harvard Business Review 20, 2: 83-97. Schafritz, J.M., and E.W. Russell. 2003. Introducing Public Administration, 3rd ed. New York: Longman. Selden, S.C., G.A. Brewer, and J.L. Brudney, 1999. “Reconciling Competing Values in Public Administration: Understanding the Administrative Role Concept.” Administration and Society 31, 3: 171-204. Selden, S.C. and D.P. Moynihan, 2000. “A Model of Voluntary Turnover in State Government.” Review of Public Personnel Administration, 20, 2: 63-74. Spector, P. E., 1997. Job Satisfaction. Thousands Oaks, CA: Sage. U.S. Merit Systems Protection Board, 2003. The Federal Workforce for the Twentieth Century: Results of the Merit Principles Survey 2000. Washington, DC. ______, 2001. Merit Principles Survey 2000. Washington, DC. Walker, R.M., and G.A. Boyne, 2004. Public Management Reform and Organizational Performance: An Empirical Assessment of the UK Labour Government’s Public Service Improvement Strategy. Working Paper. Center for Local and Regional Government Research, Cardiff University. Wolf, P.J., 1993. “A Case Survey of Bureaucratic Effectiveness in U.S. Cabinet Agencies: Preliminary Results.” Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory 3: 161–81. Wooldridge, J.M., 2003. Introductory Econometrics: A Modern Approach, 2nd ed. Cincinnati, OH: South-Western College. Youndt, M.A., S.A. Snell, J.W. Dean, and D.P. Lepak, 1996. “Human Resource Management, Manufacturing Strategy, and Firm Performance.” Academy of Management Journal. 39, 4: 836–66. 21