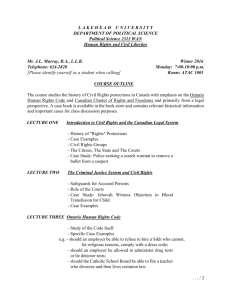

LIMITATION - Human & Constitutional Rights

advertisement