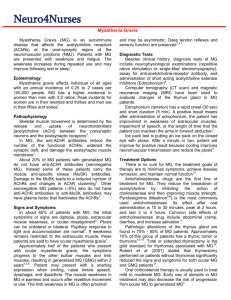

[4] Sir Bernard Katz was a winner of the Nobel Prize in

advertisement

![[4] Sir Bernard Katz was a winner of the Nobel Prize in](http://s3.studylib.net/store/data/008497748_1-b579adfb19d570e6b37c2ad850d1a0d8-768x994.png)