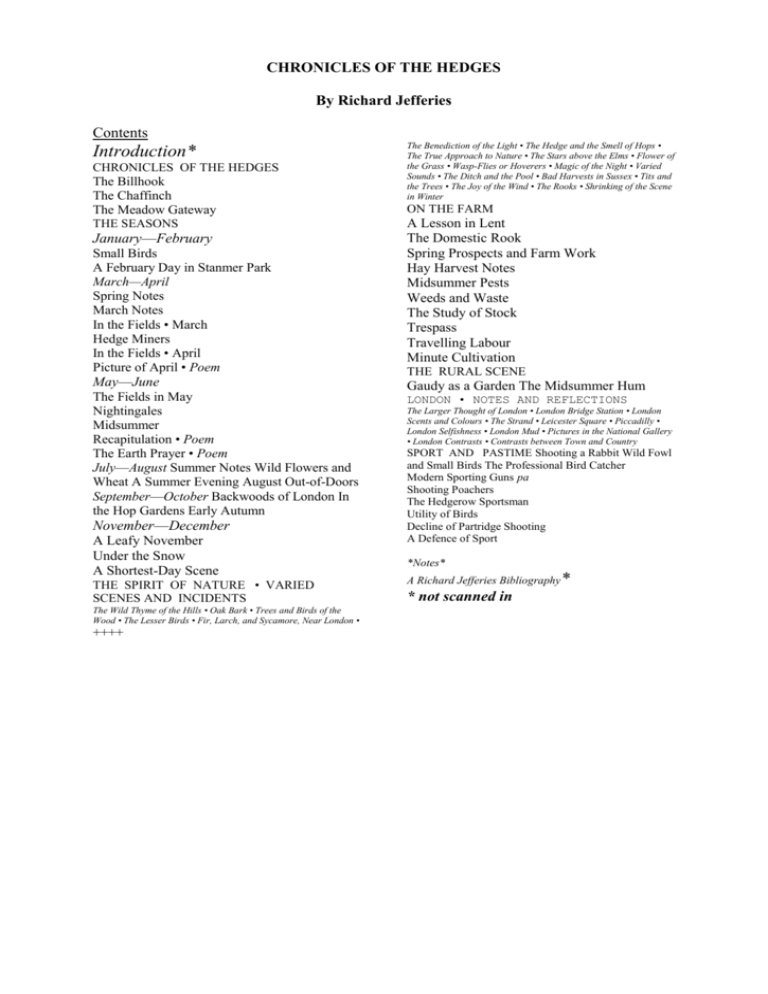

CHRONICLES OF THE HEDGES

advertisement