Negligence: Duty of Care, Breach, and Causation Explained

advertisement

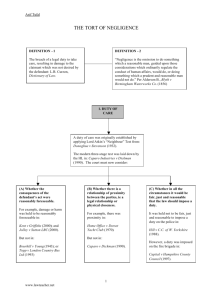

Negligence Donoghuge v Stevenson This was the case which defined the “neighbour principle” identifying who was owed a duty of care. It defined a neighbour as: “persons who are so closely and directly affected by my act that I ought reasonably to have had them in contemplation as being so affected, when I am directing my mind to the acts or omissions which are called in question.” Put more simply, a neighbour is someone who where directly affected by the act or omission, and are reasonably foreseeable that they would be affected by that act or omission. This rule allowed judges to decide who owed a duty of care, and who didn't. However they often found themselves making policy decisions to avoid certain groups owing a duty of care, despite the claimant being closely and directly affected. Hill V Chief Constable Of West Yorkshire Police (1988) It was found that the police where not liable to the families of victims for failing to prevent crime. After the mother of a woman murdered by the Yorkshire ripper tried to claim against the police for not catching the killer quickly enough, causing her daughters death. Osman V UK (2000) This was a case in the European court of human rights. The failure of the police to follow up the claimant's reports of the death of a man and injuries to that man's son was held to be a breach of the European convention of human rights. Z V UK (2001) Another European court of human rights case, this established that a local authorities failure to protect a child from abuse by the child's parents was a breach of the child's human rights. Both of these cases (Z v UK and Osman V UK) called into question the almost blanket immunity to claims that the police had enjoyed up to that point (pre 2001) since 2005 and the case of Brooks V Commissioner of police for the metropolis, the police are considered not to have a duty of care towards a victim of crime, unless the police “assume a responsibility towards that person.” Caparo V Dickman (1990) This case modified the neighbour principle into a more modern three part test. For a duty of care to be imposed three questions must be answered: Was the damage or harm reasonably foreseeable? Was there sufficient proximity between the claimant and the defendant? Is it just, fair and reasonable for a duty to be imposed? Reasonable forseeability For a duty of care to be owed, it must be reasonably foreseeable that damage or harm would occur. If a reasonable person could not foresee the damage, then no duty is owed. Bourhill V Young (1943) In this case it was held that it was not foreseeable that a woman would miscarry after hearing a motorbike accident. And so the defendant owed the woman no duty of care. Maguire V Harland And Wolff (2005) The claimant was claiming for illness caused by asbestos that had been carried into her house on her husbands work clothes. Because the exposure occurred before the dangers of asbestos where understood, it was ruled that it was not foreseeable at the time that she would get ill, and so her husbands employers owed no duty of care. Sufficient proximity This rule requires that the claimant and defendant have sufficient proximity. This is where there must be a link between the claimant and the defendant. For example there would be sufficient proximity between a person hit by a car, for obvious reasons, but there could also be sufficient proximity to the family of that person, who see them at the hospital. McLoughin V O'Brian (1983) The claimant's claim for nervous shock against a lorry driver who hit her family was successful, as it was ruled that there was a proximity between her and the lorry driver, after she saw the condition of her family in hospital. Just, fair and reasonable This requirement allows judges to make a decision on new situations as they arise. For example it was established that it was not reasonable for a taxi driver to be responsible for a drunk passenger, who was run over as he exited the taxi. This is also used in cases where the police, fire brigade, ambulance service, hospitals or similar groups are being sued, for example the judgement in Hill would today fall under this rule. Gritthis V Lindsay (1998) It was decided by the courts that it was unreasonable for a taxi driver to owe a duty of care to a drunk passenger, who was run over as he got out of the taxi. Mulcahy V Ministry Of Defence (1996) The decision in this case established that it was unreasonable for the MOD to owe a duty of care to soldiers who are injured in battle. This ruling also means that soldiers do not owe each other a duty of care during a battle. Vowles V Evans (2003) The courts decided that it was reasonable for a referee to owe an injured rugby player a duty of care. Breach Of Duty This section is where fault becomes a factor. It is not simply enough for a duty to exist, and for an outcome to have occurred, the person who owed the duty must have failed to perform that duty to the necessary “standard of care”. For example a doctor owes their patient a duty of care. If the patient dies the doctor is only liable if they failed to properly treat the patient, not if the patient died despite the doctors best efforts. Standard of care Standards of care are described in general terms. There is no legal requirement to reach the standards of a good driver, only an average driver. Because of this the standard test is the “ordinary reasonable person” e.g. “would an ordinary, reasonable doctor have failed to spot the patients heart condition” Nettleship V Weston (1971) This is the case that established that a driver is required to fulfil the standard of care of an ordinary, reasonable driver. As it is assumed that such a driver has passed their driving test, the fact that the defendant was a learner driver was unimportant, she had fallen below the expected standard of care. Bradford-Smart V West Sussex County Council The court of appeal made the ruling that the local council was not negligent for failing to prevent a pupil from being bullied on their way to and from school. Although the school is responsible for the safety of it's pupils, and while the school may have been able to stop the bullying, the school was not obliged to guarantee the safety of every pupil on their way to and from school. The test when using this test, the courts take into account factors such as: The age of the defendant (a child is not expected to reach the standards of a reasonable adult) Mullin V Richards (1998) the profession of the defendant (a normal office worker is not expected to have the medical knowledge of a doctor, and a junior doctor would not be expected to have the knowledge of a specialist, for example) Bolam V Friern Hospital Management Comitee (1957) the characteristics of the claimant (are they more vulnerable to damage, if the defendant is aware of this, they should have taken more precautions) Paris V Stepney borough council (1951) the amount of risk (if the risk was minor, the defendant may not have breached their duty) Bolton V Stone (1951), Hilder V Associated Protland Cement (1961), Chester V Afshar (2004) Reasonable precautions (if the defendant has tried to prevent damage or injury to others the duty may not have been breached. However these precautions are only deemed reasonable if they are considered common practice) Wilson V Sacred Heart primary school (1997), Latimer V AEC ltd (1952) benefits of the risk (where the risk was acceptable in the circumstances, e.g. there is a risk of breaking someone's ribs during resuscitation. However as this is a potentially life saving procedure, this risk is reasonable.) Watt V Heartfordshire County Council (1954) Damage The final requirement for negligence is damage. This means that the alleged negligence must have caused personal injury, or damage to property. For example if a driver falls below the required standard of care of an ordinary reasonable driver, but don't damage anything or anyone, no claim for negligence exists. For damage to be proven, the negligent act or omission must have caused the damage, and the type of damage must have been foreseeable. Causation This is where the courts must establish that the breach of duty caused the damage being claimed for. The test for this is the “but for” test. I.e. “but for the defendants act would the claimant have suffered the damage?” Barnett V Chelsea and Kensington hospital management committee (1968) A claim for damages was disallowed as it was shown that a doctors failure to identify arsenic poisoning was not negligence as the poisoned people would have died anyway. Thompson V Home Office (1988) The claimant was a prisoner who had been injured in a fight by another inmate with a razor blade. The claim was based on the availability of razorblades in prison being the cause of his injury. The court ruled that this was not the case, and that the claimant's attacker would have found another way to inflict the injury. Type of damage (remoteness) it is not enough for the claimant to prove that any damage was foreseeable, the type of damage that occurred must have been foreseeable. However if damage occurs and then is made worse by non-foreseeable factors. The wagon mound (1961) In this case it was established that despite a negligent oil spill having a foreseeable capacity to cause damage, it was not foreseeable that sparks from welding would ignite the oil, causing a fire. And so the defendant was not liable. Smith V Leech Brain and Co. Ltd (1962) The defendants negligence caused the claimants husband to be burned on the lip. The burn caused cancer and the claimants husband died as a result. Because the burn was foreseeable the defendant was held liable for the full extent of the injuries and therefore the victims death, even though the cancer was not foreseeable. Huges V Lord Advocate (1963) Post office workers left a hole in the road unattended. Before they left they closed the tent covering the hole, and placed paraffin warning lamps around the hole. An 8 year old (the claimant) played inside the tent, knocking one of the lamps into the hole. This caused an explosion which badly burned the claimant. They where able to claim because while the explosion was not foreseeable, burns where a foreseeable result of the paraffin lamps. Novus Actus Interveniens Sometimes a new intervening act can break the “chain of causation” this would usually be the unexpected actions of a third person, or of the claimant themselves. Proof of such an act can result in the defendant no longer being responsible for the claimants injuries. Baker V Willoughby (1970) The claimant's leg was injured during a car accident, due to the negligence of the defendant. The defendant was ordered to compensate the claimant for his injuries. However before this occurred the claimant was shot in the leg during an unrelated armed robbery and had to have it amputated (new act). The defendant argued that he should not have to pay compensation for damage to a leg that no longer existed. The court ruled that the claimant should still receive compensation. Jobling V Associated Diaries (1982) the house of lords ruled that an employer where only liable for an employees injuries up to the point when an unrelated illness prevented the claimant from working again. Res Ispa Loquitur this translates as “the facts speak for themselves” and is the legal term used when the exact sequence of events cannot be proven, but the facts show that the defendant must have been negligent. This is especially important in medical cases, where a patient wakes up from an operation in which the surgeon has been negligent. Because the patient was under general anaesthetic, they cannot be sure who exactly was to blame. Mahon V Osborne (1939) The claimant underwent an operation during which a cotton wool swab was left in her stomach. This became infected. The hospital was found negligent based on this evidence. Scott V London and St Katherine's Docks The claimant was hit by a falling bag of sugar while in the defendant's warehouse. The fact that bags of sugar do not naturally fall out of the sky meant that the court of appeal felt there was enough evidence to find the defendant liable.