Getty: A Virtual Rich Everything

advertisement

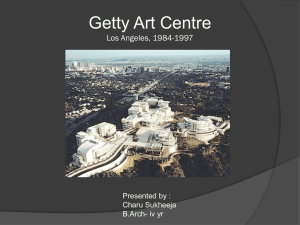

Getty: A Virtual Rich Everything Dorothy Zinberg In the city where fantasy and reality merge, the Getty Museum is redefining the role of 'educational institution' LONG before the average pre-teenager could rattle off the meaning of virtual reality as she experienced it in the "dungeons" of cyberspace, virtual reality was indelibly marked on Los Angeles life. Universal Studios and Disneyland, the home of fantasies-madereal, had long been the main attractions of Tinseltown, providing the facts and fantasies of the moving image and animation. They were the only shows in town. But the low-brow days are past. With the unveiling of the Getty Museum, LA at last has a cultural lodestar, so the city's elders and museum's planners fervently hope. Viewed solely as a museum the Getty, 13 years in the making at a staggering cost of more than $US1 billion ($1.5 billion), has received mixed reviews. However, if it were seen as a virtual university rather than just a museum the criticism would be muted. Unlike those dubious degree mills marketing themselves as virtual universities in cyberspace, the museum is virtually a university. With an endowment of $US4.5 billion, the Getty could readily provide the prototype for virtual or real universities to maximise the potential of information technology, art conservation and archaeology. It would act as the first global university for the arts. In a tough financial climate universities are rarely built from new. Smaller colleges are closing while larger, better-endowed ones are dependent on generous donors for new buildings. Rare is the donor whose largesse can bestow 300ha for a campus. The Getty offers a unique opportunity to consider the characteristics of the ideal university. What sets the Getty on the path to university status is that it houses five other major buildings and even more programs on its campus. All bear the name of their donor, the late J. Paul Getty: the Getty Research Institute for the History of Art and the Humanities, the Getty Conservation Institute, the Getty Education Institute for the Arts, the Getty Information Institute, and the Getty Grant Program. One of the big challenges facing once ivory-towered universities is how to integrate into the surrounding community so that the fruits of intellectual life -from the philosophical to the tangible are made available to more people. Whether it is working with citizens' groups to improve elementary school education or devising a plan to use the university's technical expertise and electronic systems to rescue failing local industries such as fishing or farming, universities are striving to increase their outreach while maintaining their intellectual disinterest and autonomy. The Getty has made strides in this direction and its institutes and programs have dozens of projects under way. The Getty undergraduate internships for diversity in the arts and humanities give priority to students in the LA area who want to become interns for 10 weeks in their summer to explore a subject related to museums, scholarship, conservation and education. The program states: "The selected interns will reflect the diversity of Southern California and will be exposed to issues relating to the arts in Los Angeles." Now that the draconian slashes in the enrolment of minority groups in Californian universities have begun, the Getty's commitment to minority involvement in the centre's activities is heartily endorsed by the city. At the other end of the Getty's outreach programs are almost 150 archaeological projects worldwide. In all they have supported 1500 projects in 135 countries during the past decade. Sensitivities to local governments, ethnic groups, and indigenous scholars appear to be part of the projects' planning. Universities around the world could be linked electronically to these projects. From the movies, mock-ups and vertigo-inducing cyberspace reconstructions of early civilisations that I saw during more than four hours at the Getty, the involvement of people other than the museum's own scholars appeared to be paramount in the planning and execution of the anthropological and archaeological projects. Conversely, there are specialists from 22 countries in residence already. The Internet is everywhere in evidence. Critics have argued that "everyone is doing this". True. But at the Getty the sums available are so enormous -it has spent $US770 million in the past 10 years on painting, sculptures and rare artefacts, and will continue to collect at this level. It can light the way for the greatest potential use of the new technologies. When cash-deprived faculties at "real" universities plead their case to the dean for funds to develop their information technology potential, the Getty will be in a position to provide lowcost help on what worked and what did not. They will be making a contribution to beleaguered faculties and administrators who cannot afford to experiment but need to know the best way to move into cyberspace. As for the museum itself, it is too difficult to reach. There is too little parking and public transport is hardly the preferred mode of travel in LA. To reach the heights of this Shangri La, it is necessary to take a gleaming white tram up through sinuously landscaped terrain; much like the Great Wall of China might look if it were cleaned up. The spectacular views of LA and the Santa Monica mountains (on a smogless day) are worth the trouble. But the setting is perfect for a virtual university. In most parts of the world, universities sprang up for religious or pragmatic purposes. Only when they had sufficient funds, thanks to princely and private donors or the largesse of the State or the church, did they add a museum. By reversing the order, the Getty Centre, quite unintentionally, has built the virtual university of the future: the museum came first, coupled with the best technology that riches could buy. During the few days I was in LA, the local papers were filled with the opening of the new museum. The subject was not the impressive collection of paintings or the 14 galleries of furniture and decorative arts, but rather the destructive impact the parking was having on one of the country's most expensive neighbourhoods. Then I knew the Getty was virtually a university.