Lecture 2 Insurance Law

advertisement

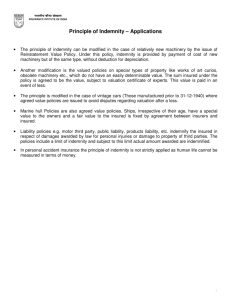

INSURANCE LAW IN IRELAND Lecture Two: General Principals of Insurance 1. Indemnity Indemnity is a fundamental principle of insurance law. It is the bedrock on which the industry has developed since the judgement of Brett LJ in Castellain - v - Preston (1883) 11 QBD 380. “The very foundation, in my opinion, of every rule which has been applied to insurance law is this, namely, that the contract of insurance contained in a marine or fire policy is a contract of indemnity, and of indemnity only, and that this contract means that the assured, in case of a loss against which the policy has been made, shall be fully indemnified, but shall never be more than fully indemnified. That is the fundamental principle of insurance, and if ever a proposition is brought forward which is at variance with it, that is to say, which either will prevent the assured from obtaining a full indemnity, or which will give to the assured more than a full indemnity, that proposition must certainly be wrong.” Re-instatement: The principle of indemnity in recent years has been eroded by insurers offering policies on a “new for old” or “re-instatement as new” basis, without deduction for wear or tear or betterment, particularly in motor insurance or property damage. Problems however arise when property is in a poor state of repair, or where the policyholder decides against re-instatement. The principle of indemnity in such circumstances can be difficult and give rise to litigation. The re-instatement as new policy is subject to the principle of indemnity in that the insured cannot recover more than his loss. The sum insured in the policy is the maximum sum payable by the insurers, but not necessarily the amount paid. The Insurer’s liability to pay for reinstatement as new is generally restricted by policy provisions. If the work of reinstatement is not carried out , or is not carried out as quickly as is reasonably practicable, the insurer is liable to pay the value of the property at the time of the loss. Assessment of value of property at time of loss is generally problematical when in Court as per Murphy - v- Wexford County Council (1921) 2 IR 230 where according to O’Connor LJ: “You are not to enrich the party aggrieved; you are not to impoverish him; you are, so far as money can, to leave him in the same position as before. In dealing with buildings destroyed or injured, the following considerations suggest themselves:— What sort of building was it? How was it actually used? Had it a possibility of a different use, a potential use, which an ordinary owner might be reasonably considered as likely to put it to hereafter? Would he, for any reason that would appeal to an ordinary man in his position, rebuild it if he got replacement damages, or is his claim for such damages a mere pretence? And, if he would rebuild, what sort of a house would he put up? Would he rebuild on the same scale, or would he adopt something else equally suitable to his requirements, having regard to modern conditions?” [This case was one of a series of cases arising out of the burning of a police barracks in the Irish war of independence. The claims were for malicious damage brought against local authorities but the compensatory principle was the same as for torts. (reinstate the status quo prior to the tort)] Example: Extent of Indemnity on Buildings: Does a particular sum paid in respect of loss or destruction of an old building, or one in a poor state of repair, amount to enrichment or impoverishment of the insured? There are 3 possible bases for establishing the value of a building: (1) Re-instatement cost: If policy provides for re-instatement as new, no deduction for wear & tear otherwise you would be forcing the owner to modernise. (2) The cost of the equivalent modern replacement: This may be used in relation to old buildings where no other suitable valuation method is available. The building’s purpose is the main factor in determining cost. (3) Market value This may be difficult if there is no ready market for a building of its type. Owner should not be forced to accept a forced market value where he had no intention of selling. This should be determined on facts of each case. In Leppard - v - Excess Insurance Company Ltd (1979) 1 WLR 512, the insured who purchased a building for a nominal price insured it for £14,000, which sum was intended to represent the full value of the building (cost of replacement in its existing form if destroyed). The insured had the property on the market for £4,500 immediately before the fire that destroyed it. The insured claimed the cost of reinstatement, less an allowance for betterment, in the sum of £8,694. The insured claimed that the sum insured which he was entitled to represented an indemnity in the amount of that full value up to the sum insured under the policy in the event of total loss. Court of Appeal held that the insured was entitled only to recover actual loss and as he was willing to sell the property for £4,500 immediately before the fire, then the real value was £3,000 (agreed value less the site). In a case relating to the valuation of fine art, some guidelines were formulated from the case of Quorum As - v - Schramm (No. 1) (2001) EWHC 494: 1. Valuation had to be in the relevant market 2. The amount recoverable by the insured was not to be reduced by the amount of commission payable 3. Although the usual rule was that the measure of indemnity was the difference in market value immediately before and immediately after the loss, it may be necessary to modify the rule to take into account the possibility of damage and restoration of the item carried out subsequently, if it is not possible to determine the value immediately after the loss. 4. Where there is no fixed market value the court must do the best it can in the light of expert evidence, the subjectivity of any assessment of quality, the importance of providence and the sale of comparable items. 2. Insurable Interest The principle of indemnity is vitally linked with the principle of insurable interest. To constitute insurable interest: (a) there must be a person or physical object exposed to loss or damage, or alternatively, there must be some potential liability that may devolve on the insured; (b) this person, object or liability must be the subject matter of the insurance, and (c) the insured must bear some relationship thereto recognised by law in consequence of which he stands to benefit by the safety of the person or object or the absence of liability, or be prejudiced by loss sustained by the person or object or by the creation of the liability. Definition: The necessary relationship of the insured to the subject -matter of the insurance, whereby he will be prejudiced by the event that constitutes a loss under the policy, or he will benefit if such an event does not arise (ie: what is insured in a fire policy is not the bricks and materials rather the interest of the insured in the subject matter of the insurance). In Lucena -v - Crauford (1806) 127 ER insurable interest was defined as: “A man is interested in a thing to whom advantage may arise of prejudice happen from the circumstances which may attend it…and whom it importeth that its condition as to safety or other quality should continue; interest does not necessarily imply a right to the whole or a part of the thing, nor necessarily and exclusively that which may be the subject of privation, but the having some relation to, or concern in the subject of insurance, which relation or concern by the happening of the perils insured against may be so affected as to produce a damage, detriment, or prejudice to the person insuring; and where a man is so circumstanced with respect to matters exposed to certain risks or dangers, he may be said to be interested in the safety of the thing.” Discuss: The idea that property of a thing is distinct from the interest of a thing. Owning something creates a price/money value whereas the measure of interest is the benefit or advantage arising there from. Statute: The Life Assurance Act 1774 was passed to avoid the possibility of abuse to prevent people gambling on the lives of others. The Act forbade the making of any policy on “the life or lives of any person or persons, or on any other event or events whatsoever, wherein the person or persons, or on any other event or events whatsoever, wherein the person or persons for whose use, benefit or on whose account such policy or policies shall be made, shall have no interest, or by way of gaming or wagering.” The Act only applies to life and personal accident policies. The Marine Insurance Act 1745 made null and void all policies of insurance issued without the requirement of an insurable interest. It was therefore illegal to effect policies on ships and goods laden on them and in lives where no insurable interest existed. The Marine Insurance Act 1788 required the existence of an insurable interest for all policies issued in respect of any ship “or any goods, merchandise, effects or other property whatsoever.” The Marine Insurance Act 1906 now declares void any marine insurance policy where no insurable interest exists at the time of the loss and defines insurable interest as a “person is interested in a marine insurance venture where he stands in any legal or equitable relation to the adventure or to any insurable property at risk therein, in consequence of which he may benefit by the safety or due arrival of insurable property, or may be prejudiced by its loss, or by damage thereto, or by the detention thereof, or may incur liability in respect thereof.” 3. Subrogation – Rights of Insurers The right of an insurer to be subrogated to the insured’s subsisting right of action. The insurer having discharged his liability under a policy, to take over and prosecute in the name of the insured all rights of action the insured might have had against persons responsible for the loss giving rise to payment under the policy. An insurer’s right to reimburse itself from third party sources did not arise until the insured has been fully compensated for his loss. The main aim of the doctrine is to prevent any infringement of the principle of indemnity by entitling insurers, after the payment of a loss, to take the benefit of any rights the insured may possess, whereby his loss may be extinguished or alleviated by recovery from other sources. In Randall - v - Cockburn (1748) 1 Ves. Sen. 98 it was held that the plaintiff insurers, after making satisfaction, stood in the place of the insured as to goods, salvage and restitution in proportion to what they had paid. As a rule of equity, subrogation supports indemnity as the central principle of insurance law. Per Castellain v Preston, subrogation was defined as follows: “as between the underwriter and the assured the underwriter is entitled to the advantage of every right of the assured, whether such right consists in contract, fulfilled or unfulfilled, or in remedy for tort capable of being insisted on or already insisted on, or in any other right, whether by way of condition or otherwise, legal or equitable, which can be, or has been exercised or has accrued, and whether such right could or could not be enforced by the insurer in the name of the assured by the exercise or acquiring of which right or condition the loss against which the assured is insured, can be, or has been diminished.” Essential elements of for Subrogation: (a) a valid contract (b) a payment by insurers under the contract (c) a connection between the subject matter of the insurance and the rights of the insured to which insurers are subrogated. 4. Double Insurance and Contribution Double Insurance Duplicate protection provided when two companies deal with the same individual and undertake to indemnify that person against the same losses. When an individual has double insurance, he or she has coverage by two different insurance companies upon the identical interest in the identical subject matter. If a Husband and Wife have duplicate medical insurance coverage protecting one another, they would thereby have double insurance. An individual can rarely collect on double insurance, however, since this would ordinarily constitute a form of Unjust Enrichment, and a majority of insurance contracts contain provisions that prohibit this. It differs from re-insurance in this, that it is made by the insured, with a view of receiving a double satisfaction in case of loss; whereas a re-insurance is made by a former insurer, his executors or assigns, to protect himself and his estate from a risk to which they were liable by the first insurance. The two policies are considered as making but one insurance. They are good to the extent of the value of the effects put in risk; but the insured shall not be permitted to recover a double satisfaction. He can sue the underwriters on both the policies, but he can only recover the real amount of his loss, to which all the underwriters on both shall contribute in proportion to their several subscriptions. Contribution Though this is a creation of the Courts of Equity, it can be confused with subrogation. The rules are complex and may seem illogical. Their purpose if to ensure that where there are two or more concurrent policies capable of responding to the insured’s loss, a claim by the insured against any one insurer allows that insurer to recover a rateable proportion of its payment from other insurers involved. If an insurer who is not liable for loss chooses to make a payment to the insures, he cannot assert a claim for contribution against another insurer. The rule confers upon other insurers the right to insist that the insurer who has paid demonstrates that the loss comes within its policy terms before seeking contribution from other insurers. The Rule also acts as a disincentive to insurers to pay the insured in full where the insurer is liable only for part of the loss. Liability of each insurer is assessed at the date of loss and not when the claim for contribution is made. In Bovis Construction Ltd. & Another v-commercial union assurance co. (2001) LRep IR. 321 it was held that an insurer who fully indemnified its insured, despite the existence of a rateable contribution clause, had been a volunteer in respect of half of the indemnity it had paid and was not entitled to recover contribution from another insurer whose policy covering the same risk included a provision that it was not to insure for the benefit of any other insurer. Essential elements of contribution: (1) All of the insurance policies concerned must have common subject matter. Extent need not be the same but it is necessary that some portion of the property destroyed in respect of which the claim is made should be common to all. (2) All policies must cover the peril that causes the loss. (3) All policies must be effected by , or on behalf of the same insured. (4) All policies must be in force at the tine of the loss and must be legally enforceable. Case Law: Zurich Insurance Co. v - Shield Insurance Co. (1988) IR (This case concerns subgrogation and contribution.) A Quinnsworth employee was injured in car as passenger driven by fellow employee. Quinnsworth was held vicariously liable as a driver and a passenger were employees in course of employment. Plaintiff insurers indemnified the driver in respect of his liability to the passenger. The motor policy extended to provide an indemnity to the driver driving with the authority of the insured and the driver was therefore insured and could have enforced the policy against the insurers irrespective of Quinnsworth’s right to do so in respect of their vicarious liability. Quinnsworth has an employer’s liability policy issued by the defendants indemnifying then against liability to pay compensation for illness or injury sustained by any employee arising from and in the course of employment by Quinnsworth Ltd. Quinnsworth could therefore have claimed indemnity under that policy in respect of their vicarious liability to the injured passenger. The Plaintiffs sought 50% contribution from the defendant on the basis that there was double insurance. SC upheld HC: Defendants argument that neither the risk nor the insured interests were the same and as the interests insured and the risks covered were different, the plaintiffs were not entitled to contribution. Thus legal interests in the subject matter must be the same for contribution to apply. [extract from the Financial Ombusman annual report 2010 report] The Financial Services Ombudsman possesses a unique legal jurisdiction which is acknowledged and frequently commented upon by the Courts. All Findings must be legally sound, but there are also legal requirements that the Ombudsman must act in an informal manner and without regard to technicality or legal form. The Bureau accordingly follows well established, yet evolving, procedures regarding how it deals with complaints. Those procedures come from a variety of sources; legislation, practice and experience and from decided court cases. Those procedures and the manner in which Findings are arrived at, inevitably give rise to on-going legal interpretation and development and so are kept under continuous review. Each complaint is dealt with on its own merits on an individual case-by-case basis and the Bureau does not operate a system of Precedent Findings similar to Precedent Judgments used in a Court of Law. The Ombudsman has greater flexibility and choice in fashioning an appropriate remedy in cases which come before him. The Ombudsman also has a broad statutory discretion for deciding whether or not a complaint is within his jurisdiction. The Ombudsman regularly exercises this discretion and consequently not every complaint made can or will necessarily be investigated. An in-house Head of Legal Services was appointed in December 2010 to advise upon and manage legal affairs on behalf of the Bureau. High Court Appeals – Findings of the Ombudsman are subject to appeal and/ or judicial review to the High Court. In the course of 2010 a number of appeals were decided upon by the High Court with a number of ex tempore and written Judgments delivered. As of 31st December 2010, there were 32 High Court appeals and 1 High Court Judicial Review pending, i.e. Court proceedings were in being and either were awaiting hearing or had been heard and were awaiting Judgment. During 2010, 2 Supreme Court appeals were dealt with; Judgment was delivered in one (Davy Case below), and one was withdrawn. Appeals are brought by both Complainants and Financial Service Providers depending on the issues arising from the Finding under appeal. The majority of appeals tend to be in respect of the merits of the Finding rather than Judicial Reviews. An appeal on the merits does not involve a complete de novo, re-hearing of all issues by the High Court, rather, for an appeal to succeed, an appellant must show a significant error or series of errors by the Ombudsman in arriving at his Finding. A number of appeals are settled prior to hearing, which may include the Bureau agreeing to have a case remitted to the Ombudsman for re-consideration. It is the policy of the Bureau to seek and pursue legal costs in all appropriate cases. While most of the Court Judgments have no wider application beyond the individual appeals themselves, there is a recurring theme running throughout Judgments of the Court’s continual recognition of the Ombudsman’s unique statutory function. J&E Davy t/a Davy Stockbrokers –v- FSO, Ireland & the Attorney General and Enfield Credit Union – Supreme Court Judgment May 2010 – This Judgment is of particular importance to the Bureau and worthy of individual note. The Supreme Court delivered its Judgment on 12 May 2010 on the appeal and cross-appeal brought by the Ombudsman and Davy respectively, against the July 2008 High Court Judgment of Mr. Justice Charleton. The High Court had granted a judicial review of the then Ombudsman’s Finding, quashing the decision and remitting the matter back for re-investigation and adjudication. As set out in the 2009 Annual Report, a re-investigation and adjudication did not ultimately arise as Enfield Credit Union withdrew its complaint during August 2008. In its Judgment the Supreme Court upheld some of the findings of the High Court and overturned others. Significantly, there is much in the Judgment which supports the approach of the Bureau and confirms the Bureau’s view of the unique jurisdiction of the Ombudsman. The Judgment confirms the informality of the Bureau’s procedures, the guiding principle of fairness and the lack of necessity to mimic court procedures. The Judgment brought judicial clarity to a number of important matters affecting the Bureau and the handling of complaints. The procedures of the Bureau had already been revised in 2008 following the High Court decision and no further revisions were required as a result of the Supreme Court Judgment. These revised procedures are in line with the Supreme Court decision and continue to be employed. Enforcement Cases – in a very small number of cases the Ombudsman, pursuant to his statutory powers,engages in enforcement proceedings against Financial Service Providers who fail to comply with Findings of the Ombudsman. Financial Services Ombudsman - Bi-Annual Review Media Release – September 2012 Financial Services Ombudsman - Bi-Annual Review The Financial Services Ombudsman (FSO) William Prasifka publishes his Office’s Bi-Annual Review (January to June 2012) on 13 September, available online. The Review shows that: 3,700 complaints against Financial Institutions were received in first half of 2012, a 5% increase on the last 6 months of 2011 Trends show an increase in complaints received and an increase in complaints upheld 40% of complaints against Banks relate to Mortgages, with ‘tracker’ rate issues, maladministration and repayments terms the main areas of complaint Insurance complaints increased by 15% Complaints about Payment Protection Insurance (PPI) doubled, from 218 to 410 74% of PPI complaints are about alleged mis-sale of the product The Bureau has increased the number of Findings issued by 12%, reducing waiting times for complaint adjudication 25% of complaints received were settled by Financial Institutions The Bureau received 11,300 telephone queries during January to June 2012 and 39,000 website hits In publishing the Review, Mr Prasifka states: ‘The level of complaints received and the outcome of Findings are of serious concern. Trends indicate deterioration in complaint handling by Financial Institutions and increased dissatisfaction by consumers across a number of areas. The FSO always encourages Institutions to engage with Consumers to resolve complaints as soon as possible. While 25% of complaints were settled by Institutions, the increase in complaints received and complaints upheld by the FSO shows that Institutions are still not doing enough to engage with consumers at an earlier stage. The alleged mis-selling of PPI products has resulted in a doubling of PPI complaints in 6 months and trends suggest this increase will continue. Other recent, well-publicised problems in certain Financial Institutions will test Institutions’ willingness to address failings at an early stage and show whether or not Institutions are genuinely committed to resolving complaints before referral to the FSO.’