Report to the World Bank on the Malaysian Venture Capital Industry

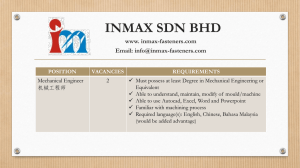

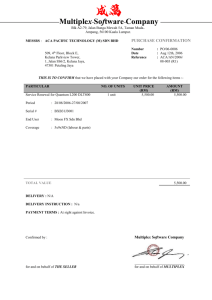

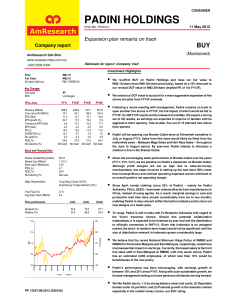

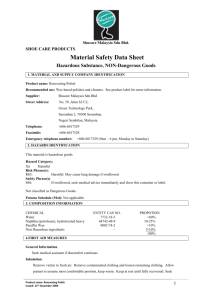

advertisement