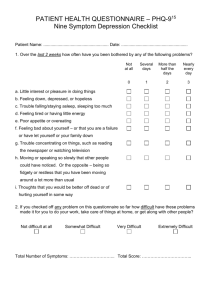

How to use the questionnaire procedure in cases of disability

advertisement