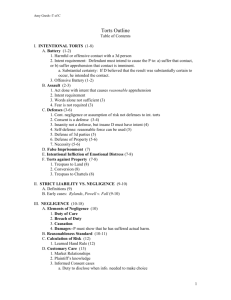

Torts Outline

advertisement