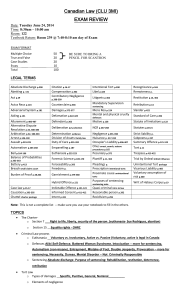

Dobbs and Hayden, Torts and compensation 4th ed (West, 2001)

advertisement