The United States' Approach to Ethanol: Tarrible or Tariffic? (2007)

advertisement

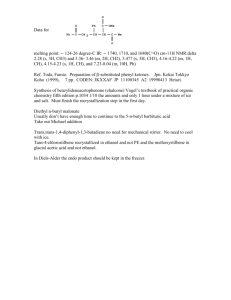

Reed Mettler May 4, 2007 Econ 311 – 1:30 Professor Whitney Final Paper The United States’ Approach to Ethanol: Tarible or Tariffic? --An International Economics Perspective -Since the oil crises of the late 1970s, much attention has been focused by states the world over on how to achieve “energy security”—that is, independence from foreign sources of energy. The recent increase in innovations in and use of renewable energy technologies (i.e. solar, hydro, geothermal, wind, etc.), cleaner carbon technologies (i.e. carbon capture, cleaner burning practices, increased efficiency, etc.), and the like can all be seen as a direct response to this threat of dependency. Another major factor in this shift, and the reason it has tended largely toward cleanliness and efficiency, are concerns about the environment. Global warming, or “climate change,” has become a major focus of both domestic and international spectra in the recent decades. Acknowledging the fact that the way in which we currently use energy is harming the earth, holding in store a multitude of devastating consequences for our future, has helped liven and quicken the pace toward greater implementation of the advanced and alternative energy sources mentioned above. The most notable and pursued alternative energy source as of late provides both national security with regards to energy independence and hope for the environment: ethanol. “Ethanol is an alcohol-based alternative fuel produced by fermenting and distilling starch crops that have been converted into simple sugars.”1 It can be manufactured from crops such as corn, wheat, grass, and sugar cane and, therefore, has U.S. Department of Energy, “Alternative Fuels Data Center, Ethanol,” 4 June 2006; <http://www.eere.energy.gov/afdc/altfuel/ethanol.html>, accessed 1 May 2007. 1 Mettler, 2 great potential for domestic production by states around the world. This biofuel is also much cleaner to produce than conventional gasoline and is less harmful to the environment upon being used. Whether you know it or not, ethanol has already crept its way into our everyday lives. It is currently being used as an additive in gasoline, mixed in at refineries, usually to the tune of approximately 10% per gallon, but in some places at up to 85%—this concentration, as opposed to the former, is considered an alternative fuel under the U.S. Energy Policy Act of 1992.2 All of these pressures and incentives for the increased use and distribution of ethanol can be seen throughout the world. Demand is growing in many states as is production, with Brazil and the United States currently the two largest producers of ethanol. Though Brazil is the largest exporter, the United States is still importing ethanol from other states in order to cover excess demand. (See figures 1a, 1b, and 1c) This rising demand in the U.S. is rooted in a variety sources. First, the use of ethanol is increasing as “the phasing out of methyl tertiary butyl ether (MTBE) – an oxygenate blended with petrol that was intended to replace lead in gasoline – in the United States” becomes fully effective.3 A second, and perhaps more powerful, push were the State of the Union address given by President Bush in 2006, calling for “Americans to start using more renewable fuels, …[such as] ethanol…, as a way to reduce U.S. dependence on foreign oil,” and a bill passed by Congress “requiring the U.S. oil industry to use 7.5 billion gallons a year of renewable fuels by 2012, most of which is…to be ethanol.”4 2 Ibid. Juliette Kerr, “Brazil’s Finance Minister Asks U.S. to Reduce Ethanol Tariff; Domestic Prices Fall,” Global Insight (25 April 2006). 4 Lauren Etter, “Can Ethanol Get a Ticket to Ride?; Meanwhile, Imports Are Rising,” Wall Street Journal, 1 Feb. 2007, B1. 3 Mettler, 3 The United States has had to implement several international and domestic trade oriented policies in order to pursue its dreams of supremacy and importance in the rapidly growing global ethanol market in competition with several other states, who all have similar plans. These protectionist actions, though they disrupt the natural flow of market trends toward efficiency, are “necessary” because the United States is not only several steps behind Brazil with regards to production, use, and exportation of ethanol as a fuel, but also because the type of ethanol that the United States is producing is inferior to that which is produced in Brazil. Statistics show that maize (corn) based ethanol, the type manufactured in the United States, “yields only 30 percent more energy than what is used to produce it. By contrast, Brazilian sugarcane yields 700 to 800 percent more energy [as ethanol] than is used in its production.”5 In addition, “Brazil can produce ethanol for as little as 80 cents a gallon, less than half the price of U.S. ethanol producers…[because] sugar cane…ferments more quickly into alcohol.” Furthermore, Brazilian resources and processing methods are so efficient and cost-effective that it is sometimes cheaper for U.S. buyers to purchase ethanol directly from Brazil, despite the rigidly enforced trade restrictions which increase the end-user cost by upwards of, and usually much more than, 67 percent.6 (See figure 2) These figures are very telling of the comparative advantage which Brazil obviously currently has over the United States with regards to ethanol production and distribution. International economics theory states, in layman’s terms, that “a country should export what it does most best or least worst and import what it Wire Feed, “Brazil/U.S.: Environmentalists Decry Ethanol Alliance,” Global Information Network, New York, 3 April 2007. 6 Lauren Etter and Joel Millman, “Alternative Energy: Ethanol Tariff Loophole Sparks a Boom in Caribbean; Islands Build Plants To Process Brazil’s Fuel; Farm Belt Cries Foul,” Wall Street Journal, 9 March 2007, A1. 5 Mettler, 4 does least best or most worst.”7 While an additional product would be required for an exact comparative analysis assessment, Brazil’s higher productivity margin and higher efficiency (both in production methods and of end-product) dictates that it should export ethanol and that the United States should import it.8 However, the United States has another agenda; which is signified by the restrictive trade policies it continues to implement, distorting the natural flow of products between states around the world. One policy, in particular, has received much attention domestically and internationally: the United States’ import duty on ethanol from Brazil. (See figure 2) The following paragraphs will provide an economic analysis of this tariff including discussions of the specifics of the policy, the foreign and domestic pressures which oppose and keep it in place, and the consequences of the measure on the fledgling global ethanol market and the world as a whole. The U.S. ethanol import tariff, recently extended until 2009, currently requires that Brazilian exporters of ethanol pay 54 cents to the United States per gallon of ethanol imported. This trade restriction is a “specific” tariff, which implies a targeted dollar per unit fee.9 Continued support for this measure, and the pressure behind its extension, can be traced back to “the disproportionate representation of rural interests in the U.S. Senate.”10 Any thought of repeal or review of the tariff will be met by stiff opposition by these “corn-country Republicans,” who “are gearing up for a fight.”11 This position is not only present within the hearts of certain congressional representatives, but also pursued Jim Whitney, “Class Notes – Economics 311,” Day 4, 29 Jan. 2007. Etter and Millman, “Alternative Energy: Ethanol Tariff Loophole…” 9 Ibid. Day 16, 2 Feb. 2007. 10 Holman W. Jenkins, “Business World: Ethanol Liberation Movement,” Wall Street Journal, 14 March 2007, A14. 11 Ibid. 7 8 Mettler, 5 strongly by groups which lobby on behalf of American corn farmers. The logic behind their position is summed up by Matt Hartwig, spokesman for Renewable Fuels Association, an ethanol trade group. He states that ending the tariff will not increase U.S. ethanol supply or lower prices due to Brazil’s already tight ethanol supply. In addition, he argues that this action will “discourage investment in domestic ethanol production projects.”12 Despite Hartwig’s dismissal of the facts that Brazil is currently expanding its production facilities13 and that production subsidies would still provide incentives for production projects (without the negative national welfare effects of the tariff – see figure 3) his position still seems to hold weight on the Hill. The consequences of the sway of lobbying groups does not stop there, however. Beyond the effects of the policies they solidify, they also cause further harm to national welfare by simply doing their job. (See figure 4) Though U.S. officials, in dialogue with all actors, refer to the tariff as a “congressional measure,” these other actors still voice their warranted, and well-founded, opinions.14 The opposing side to the argument of the trade restriction comes from other states and also, more surprisingly, from within the United States as well. The main proponent for the drop of the tariff is, of course, Brazil. Eduardo Carvalho, President of Brazilian Sugarcane Industry Union, makes a clear point by noting that “the oil derivatives market operates on the basis of free trade…we cannot accept that ethanol trade is conducted in a 19th-century manner, with market protections.”15 Though this union is obviously another Chemical News & Intelligence, “Refiners Seek Suspension of US Tariff on Ethanol,” 23 May 2006. David J. Lynch, “Brazil Hopes to Build on its Ethanol Success; Nation Aims to Turn Alternative Fuel into a Global Commodity,” USA Today, 29 March 2006, Money 1B. 14 Josh Schneyer, “Ethanol Talks to Dominate Bush’s Brazil Visit; Trade Barrier to Remain, No Change on Import Tariff: Analysts,” Platts Oilgram News, 9 March 2007, 1. 15 Greenwire, “Brazil Says Removing U.S. Import Tariff ‘On the Table’ During Upcoming Meeting,” 2 March 2007, Business, Finance & Technology. 12 13 Mettler, 6 lobbying group, they are openly supported by the President of Brazil and many other parties within the state. Also, despite the fact that this statement has been used in many forms by many states who have preeminence in a particular market, it does make clear that global growth in this sector will be extremely difficult with continued restrictions by such an important player as the United States. Attempts to ask for a tariff-free export quota, as proposed by Brazil, could be a possible midpoint for the ethanol market on its move toward unrestricted free trade.16 However, this would take U.S. cooperation which, as noted above, may be difficult to muster. Hope may come with the fact that there are some in the United States who would like to see a decrease or removal of the tariff. Bob Slaughter, president of the National Petrochemical & Refiners Associate, notes that “increased imports could ease…runaway price inflation in ethanol…as prices have more than doubled in the past year.”17 Amid demands within and without the United States to fully open the ethanol trade market countered by requests for protectionism by farmers who inefficiently produce low-quality ethanol, it will be interesting to see what path the White House and Congress decide to take: lower trade restrictions? drop the import tariff? provide financial and technological support to American farmers? attempt to increase production overseas? or some combination of one or any other of the countless possibilities? There is one thing of which we can all be certain, however. The current path we are following is neither efficient in terms of trade or equitable in terms of the improvements which ethanol could bring to our world; and that is simply not sound economics. Chemical News & Intelligence, “Brazil Industry Seeks US Tariff-Free Quota for Ethanol,” 14 March 2007. 17 Chemical News Intelligence, “Refiners Seek…” 16 Mettler, 7 Bibliography Chemical News & Intelligence. “Brazil Industry Seeks US Tariff-Free Quota for Ethanol,” 14 March 2007. Chemical News & Intelligence. “Refiners Seek Suspension of US Tariff on Ethanol,” 23 May 2006. Etter, Lauren. “Can Ethanol Get a Ticket to Ride?; Meanwhile, Imports Are Rising,” Wall Street Journal, 1 Feb. 2007, B1. Etter, Lauren and Joel Millman. “Alternative Energy: Ethanol Tariff Loophole Sparks a Boom in Caribbean; Islands Build Plants To Process Brazil’s Fuel; Farm Belt Cries Foul,” Wall Street Journal, 9 March 2007, A1. Greenwire. “Brazil Says Removing U.S. Import Tariff ‘On the Table’ During Upcoming Meeting,” 2 March 2007, Business, Finance & Technology. Jenkins, Holman W. “Business World: Ethanol Liberation Movement,” Wall Street Journal, 14 March 2007, A14. Kerr, Juliette. “Brazil’s Finance Minister Asks U.S. to Reduce Ethanol Tariff; Domestic Prices Fall,” Global Insight (25 April 2006). Lynch, David J. “Brazil Hopes to Build on its Ethanol Success; Nation Aims to Turn Alternative Fuel into a Global Commodity,” USA Today, 29 March 2006, Money 1B. Schneyer, Josh. “Ethanol Talks to Dominate Bush’s Brazil Visit; Trade Barrier to Remain, No Change on Import Tariff: Analysts,” Platts Oilgram News, 9 March 2007, 1. Whitney, Jim. “Class Notes – Economics 311,” Day 4, 29 Jan. 2007. Wire Feed. “Brazil/U.S.: Environmentalists Decry Ethanol Alliance,” Global Information Network, New York, 3 April 2007. U.S. Department of Energy. “Alternative Fuels Data Center, Ethanol,” 4 June 2006; <http://www.eere.energy.gov/afdc/altfuel/ethanol.html>, accessed 1 May 2007. Mettler, 8 For Further Reading There are several other aspects to the United States/Brazil ethanol trade debate that are very interesting in their own right: The first are claims of negative externalities which result from the ethanol trade. While environmental groups tend to focus on the degradation to forests and other ecosystems, both Fidel Castro and Hugo Chavez argue that the ethanol trade (specifically the use of corn for fuel) exacerbates world hunger. Friedman, Thomas L. “Dumb as We Wanna Be [Op-Ed],” New York Times, 20 Sept. 2006, A27. Global Information Network. “Brazil/U.S.: Environmentalists Decry Ethanol Alliance,” New York, 3 April 2007. Kenny, Zoe. “US-Brazil Biofuel Plan Will Condemn 3 Billion People to Death, Says Fidel,” Los Angeles, 15 April 2007. The second is a 1983 agreement signed during the Cold War to combat Communism in the Caribbean. While this document, the Caribbean Basin Initiative, may have served different, more political purposes in the past, it is being used today as a way to skirt around the US tariff on Brazilian ethanol. Businesses are bringing hydrated ethanol from Brazil (about 5% water) to islands represented under this pact and dehydrating it (to about 1%). This “changed” ethanol is now able to enter the U.S. duty-free. Greenwire, “Biofuels: Caribbean Set to Become Hub for Ethanol Producers Seeking to Avoid U.S. Tariff,” 9 March 2007, Business, Finance & Technology . Guebert, Alan. “Prepare for Big Ethanol Imports Under Free-Trade Pacts,” Lincoln Journal Star, 26 June 2005, 3. Mettler, 9 Mettler, 10 Mettler, 11