4. Misrepresentation

advertisement

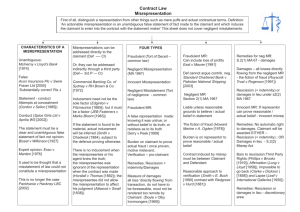

イギリス・コモンウェルス法 Good faith, duty to negotiate in good faith, and misrepresentation 高橋宏司 Optional reading: - Koji Takahashi, "Walford v. Miles in Japan: lock-in and lock-out agreements in Sumitomo v. UFJ" [2009] Journal of Business Law pp. 166-182 <http://www1.doshisha.ac.jp/~tradelaw/PublishedWorks/WalfordvMilesinJ apan.doc> - 高橋宏司「消費者契約における情報提供、不招請勧誘および適合性の原則に関する イギリスの法制度」 別冊 NBL No.121 (2008 年) 58-76 頁 1. No general concept of good faith English law is reluctant to embrace broad general principles, such as a duty of good faith. A broad general principle would generate too much uncertainty. -When would a duty of good faith arise? -What would be its content? -Is good faith a subjective standard or an objective one? -Should it apply to all contracts, or only in a noncommercial context where the need for certainty is less pressing? Occasional harsh results may be an acceptable price to pay in the interest of a majority of commercial parties who prefer certainty and predictability. 2. Denial of duty to negotiate in good faith Walford v Miles [1992] 2 AC 128 The defendants were the owners of a company and they entered into negotiations with the claimants for the sale of the company. On 17 March 1987 the parties entered into an agreement which constituted a `lock-out' agreement (in that it sought to prevent the defendants from continuing negotiations with third parties). The defendants subsequently decided not to deal with the claimants and they agreed to sell the company to a third party on 30 March 1987. The claimants sought to recover damages in respect of the breach of the agreement of 17 March, while the defendants argued that the agreement was 1 unenforceable on the ground that it was too uncertain. Held: The lock-out agreement could not be enforced because it was not limited to a specified period of time. The argument that a term should be implied that it was to last a reasonable period of time was rejected. The court refused to imply a ‘lock-in’ agreement (in that it purported to oblige the defendants to negotiate with the claimants) on the ground that an agreement to negotiate is not an enforceable contract because it is too uncertain to have any binding force. The claimants asserted that the defendants were obliged to continue the negotiations in good faith. Lord Ackner rejected this argument, stating that a' concept of a duty to carry on negotiations in good faith is inherently repugnant to the adversarial position of the parties involved in negotiations' and that `each party is entitled to pursue his (or her) own interest, so long as he avoids making misrepresentations'. “[Walford] claimed and were awarded their costs, fixed at the sum of £700, incurred from March 17 until Mr. Miles broke off the negotiations with [Walford] at the end of that month. These included in particular the costs of preparing the draft sale agreement, and they were awarded by the judge as damages for negligent misrepresentations made by Mr. Miles to Mr. Walford in the telephone conversation of March 17.” 3. Denial of the duty of disclosure Fried, Contract as Promise (1981) p 79: `An oil company has made extensive geological surveys seeking to identify possible oil and gas reserves. These surveys are extremely expensive. Having identified one promising site, the oil company (acting through a broker) buys a large tract of land from its prosperous farmer owner, revealing nothing about its survey, its purposes or even its identity. The price paid is the going price for farmland of that quality in that region: An English court would undoubtedly uphold the validity of such a contract and would not require the buyer to disclose his information to the seller prior to the making of the contract.’ “caveat emptor” (Buyer, beware.) Exceptions - Some types of consumer contracts, e.g. timeshare, financial contracts - Insurance contracts (`uberrimae fidei' or utmost good faith) 2 4. Misrepresentation Misrepresentation = false representation cf. truthful representation Fraudulent misrepresentation – deliberate misrepresentation Negligent misrepresentation – careless misrepresentation Innocent misrepresentation – misrepresentation made in the belief based on reasonable grounds that the representation is true. a. Remedies - Remedies available for fraudulent misrepresentation rescission damages - Remedies available for innocent misrepresentation rescission damages in lieu of rescission (s 2(2) of the Misrepresentation Act 1967) The remedy of rescission can be lost easily by, for example: ・ The representee affirming the contract once aware of the misrepresentation (Long v Lloyd (1958 CA)); ・ The representee delaying rescission Leaf v International Galleries (1950 CA) In 1944 the defendants sold to the plaintiff a picture which they represented to have been painted by J. Constable. In 1949 the plaintiff tried to sell it at Christies and was then informed that it had not been painted by Constable. He brought an action in which he claimed rescission of the contract and repayment. Held, the equitable remedy of rescission for an innocent misrepresentation was not open to the buyer in this case as it had not been exercised within a reasonable time. “The buyer … had ample opportunity for examination in the first few days after he had bought it.” ・ The representee being unable to restore what has been acquired under the contract (Erlanger v New Sombrero Phosphate (1878 HL)); or ・ The intervention of the rights of an innocent third party. 3 Misrepresentation Act 1967 2(1) Where a person has entered into a contract after a misrepresentation has been made to him by another party thereto and as a result thereof he has suffered loss, then, if the person making the misrepresentation would be liable to damages in respect thereof had the misrepresentation been made fraudulently, that person shall be so liable notwithstanding that the misrepresentation was not made fraudulently, unless he proves that he had reasonable ground to believe and did believe up to the time the contract was made that the facts represented were true. - Remedies available for negligent misrepresentation (s 2(1) of the Misrepresentation Act 1967) rescission damages damages in lieu of rescission b. S offered to sell his flat to B. He papered the wall in the dining room and concealed dry rot but said nothing about it. B, impressed by the interior of the dining room, bought the flat. Did S make an actionable misrepresentation? See Gordon v. Selico (1986) 11 HLR 219. c. S offered to sell a block of flats to B. B’s intention was to let the flats. S told B that the flats were fully let, which was true, but did not disclose that all the tenants had given notice to quit. B bought the flats on the strength of S’s statement. Did S make an actionable misrepresentation? See Nottingham Patent Brick and Tile Co v. Butler (1866) 16 QBD 778 A purchaser of land asked the vendor's solicitors whether the land was subject to restrictive covenants. The solicitor replied that he was not aware of any, but failed to add that this was because he had not troubled to read the relevant documents. It was held that, although the solicitor's statement was true so far as it went, it nevertheless amounted to a misrepresentation. d. S offered to sell his company to B. S told B that the company was profitable. This was true. Later, but before the sale, the company ceased 4 to be profitable. S said nothing about this change. B bought the company on the strength of S’s statement. Did S make an actionable misrepresentation? See With v O'Flanagan [1936] 1 All ER 727 e. S offered to sell B a farm in New Zealand, which had not been used for sheep farming before, represented to B that, in his judgment, the land could carry 2000 sheep. In fact it could not carry 2000 sheep. Did S make an actionable misrepresentation? Bisset v. Wilkinson [1927] AC 177 Smith v Land & House Property Corporation (1884 CA) While negotiating the sale of some premises the vendors, Land & House, described the tenant as 'a most desirable tenant.' In reality, the tenant, had a history of rent arrears, and was actually in arrears at the time of the representation. The vendors' opinion was held to be an actionable misrepresentation. Bowen LJ said: … if the facts are not equally well known to both sides, then a statement of opinion by one who knows the facts best, involves, very often, a statement of material fact, for he impliedly states that he knows facts which justify his opinion. Esso Petroleum Ltd v Mardon [1976] QB 801 per Lord Denning M.R. If a man, who has or professes to have special knowledge or skill, makes a representation by virtue thereof to another--be it advice, information or opinion--with the intention of inducing him to enter into a contract with him, he is under a duty to use reasonable care to see that the representation is correct, and that the advice, information or opinion is reliable. f. Y offered to let his house to a young solicitor X, who was looking for a cottage in which to spend his holidays with his young wife. Y described the house as `suitable as a retirement home'. X rented the house but when he arrived at the house with his wife, he found out that it was in fact not suitable for elderly residents because it had a very narrow staircase. Can X rescind the contract for misrepresentation? 5 g. S offered to sell his DVD recorder to B. S told B that it was in working order. This was untrue. However, B inspected the condition of the DVD recorder himself. B then bought the recorder solely on the strength of his own inspection. Two days later, B now regrets having bought the recorder. Can B rescind the contract for misrepresentation? Attwood v Small (1838) (3 Y. & C. Ex. 105) h. S offered to sell his DVD recorder to B. S told B that it was in working order. This was untrue. S invited B to have the recorder tested independently before buying it. However, without taking up the invitation, B bought the recorder on the strength of S's statement. Two days later, B now regrets having bought the recorder. Can B rescind the contract for misrepresentation? Redgrave v Hurd (1881) 20 Ch D 1, CA, per Jessel MR: If a man is induced to enter into a contract by a false representation, it is not sufficient answer to him to say, 'if you had used due diligence you would have found out that the statement was untrue.’ Contributory negligence operates to reduce or extinguish the amount of damages that the representee is entitled to: Gran Gelato v Richcliff (1992 HC). However, it does not operate where a fraudulent misrepresentation has occurred: Standard Chartered Bank v Pakistan National Shipping (No 4) [2001] QB 167 i. S offered to sell his DVD recorder to B. S told B that it was in working order. This was untrue. However, B inspected the condition of the DVD recorder. B then bought the recorder partly on the strength of his own inspection and partly on the strength of S's statement. Two days later, B now regrets having bought the recorder. Can B rescind the contract for misrepresentation? See Edgington v Fitzmaurice (1885 29 Ch D 459) The directors of a company issued a prospectus inviting subscriptions for debentures, and stating that the objects of the issue of debentures were to expand the business. The real object of the loan was to enable the directors to pay off liabilities. The Plaintiff advanced money on some of the debentures under 6 the erroneous belief that the prospectus offered a charge upon the property of the company but he also relied upon the statements contained in the prospectus. The company became insolvent. Held that the misstatement of the objects for which the debentures were issued was a material misstatement of fact, influencing the conduct of the Plaintiff, although the Plaintiff was also influenced by his own mistake. 7