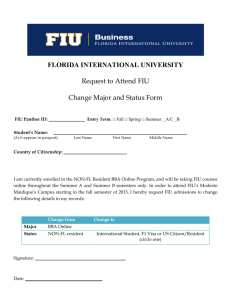

Florida Board of Governors - State University System of Florida

advertisement