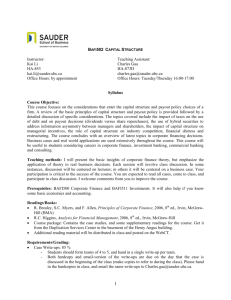

Healthy lives, Healthy people

advertisement

Introduction On 30 November, the Secretary of State for Health in England launched the White Paper, Healthy Lives, Healthy People, which sets out the Government’s long-term vision for the future of public health in England. Since the early autumn, in anticipation of the publication of the White Paper, the BMA has hosted a series of meetings attended by all major English public health organisations - including the Faculty of Public Health (FPH), the Royal Society for Public Health (RSPH), the UK Public Health Association (UKPHA), the Association of Directors of Public Health (ADPH), the Royal College of Nurses (RCN) and the Chartered Institute of Environmental Health (CIEH). Many of these meetings have also been attended by members of the Public Health Development Unit (PHDU) at the Department of Health, and have been useful in enabling the exchange of ideas and concerns in a receptive atmosphere. As part of its work on the Public Health White Paper (PHWP), the BMA has also met with other health organisations, including medical Royal Colleges, as well as organisations with an interest in public health such as the Local Government Association (LGA). Additionally, the BMA organised a “Listening Event” on 12 January 2011, which was attended by almost 200 public health specialists. The report1 of the day was subsequently handed to Anne Milton, Parliamentary Under Secretary for Public Health, and has also been sent with this response. This report captures the breadth and depth of the public health community’s voice in an unprecedented manner. Therefore, whilst this response is that of the BMA alone, we are certain that the issues that we raise are also ones which are causing concern across all organisations with an interest in public health. 1 Public Health: Our Voice http://www.bma.org.uk/images/publichealthbriefingourvoicemar2011_tcm41-204472.pdf - Summary The BMA, together with the other organisations with an interest in public health, is responding to the public health white paper, Healthy Lives, Healthy People, whilst simultaneously responding to a Health and Social Care Bill, which also covers public health in some depth. The landscape is further complicated by the fact that primary care trusts (PCTs) and strategic health authorities (SHAs) are already divesting themselves of staff and responsibilities, before the remit of the organisations due to take their place are fully known. There is a danger that any commentary on Healthy Lives, Healthy People, could be like discussing the strength and suitability of the bolt on the stable door whilst the horse has already galloped off into the distance. However, whilst this disordered transition period has added to the anxiety of the public health community, it is not the main cause of their concerns. There is a real worry across the public health community that the future structure of the public health service envisioned by the government is fatally flawed. Sending different elements of public into different organisations, with different cultures and approaches, both to the NHS and each other, could lead to the fragmentation of public health. These concerns are very much in evidence in Public Health: Our Voice2, the report of the BMA hosted event on 12 January on the NHS reforms, attended by 200 public health medical and non-medical specialists. It is for this reason that in the BMA’s preferred model, all public health specialist staff would be identified and transferred to a single public health agency. This would be an NHS organisation which would second them to Local Authorities as needed. As such, it would include all three domains of public health practice – health protection, health improvement, and public health support for commissioning. This model has much in common with one recently published in the Lancet3. The BMA believes that the creation of this model has several additional benefits over the one suggested by the government. These include: Co-ordinated training and career progression More robust emergency planning and better emergency resilience The continued ability of the Health Protection Agency (HPA) to generate income Public health retaining its independence from political interference, either at a local or national level Minimising disruption and stress to public health staff by ensuring that they can maintain their NHS terms and conditions which will also allow public health to remain an attractive career option for trainees The BMA has significant reservations about the power that the proposed reforms will enable public health specialists to wield within in local authorities. The major factor for success will be whether the Director of Public Health and the specialist team are able to have control and lead local public health. For this to occur, directors of public health need to have full veto over the ring fenced public health budget They will need to be prepared to give account of their actions to the local population and elected representatives should they fail to deliver measured change in the 2 www.bma.org.uk/images/publichealthbriefingourvoicemar2011_tcm41-204472.pdf Public health in England: an option for the way forward, Martin McKee et al, 28 February 2011. 3 1 local public's health. The profession is asking for authority, but it also is prepared to accept responsibility. Finally, it is vital that any reform of public health takes into account all three of its domains; health protection, health improvement and health care public health (support for commissioning). Too often the term “public health” is conflated to mean only one or both of the first two domains, and the commissioning aspect remains unaccounted for. More than ever, the NHS needs the expertise of such a specialist workforce, who are highly trained in commissioning services. Yet the Health and Social Care Bill, Liberating the NHS and Healthy Lives, Healthy People, pay little, if any, attention to their future. 2 General Comments This, the main section of the BMA’s response to Healthy Lives, Healthy People, is concerned with the proposed restructuring of the public health workforce. This is because it is this restructuring which forms the basis for the consultation questions for the White Paper as well as the related consultation documents on the Outcomes Framework and the Funding and Commissioning streams. For details on the BMA’s view of the scientific evidence which makes up much of the White Paper, and provides the government’s motivation for carrying out the structural reforms, please see the Appendix. The proposed reforms to the public health system in England, as outlined in the government’s consultation Equality and Excellence: Liberating the NHS, the subsequent Health and Social Care Bill and in this White Paper, have caused great anxiety amongst public health community. This anxiety is noticeable to anyone speaking to a public health doctor on the future of their specialty and was particularly in evidence at a “Listening Event” hosted by the BMA on the 12 January 2011. The event was attended by almost 200 public health specialists (including medics and non-medics) many of whom expressed concern not only for their own roles, but for the very future of public health. The public health community’s concerns can be broken into two distinct sections; concerns over the future structure of public health; and concerns around the transition period to this new structure. The transition period The process for the transition of public health to local authorities is very uncertain for public health and the BMA believes that more details on this process are needed from government. There is a danger of losing public health staff and expertise during this transition; especially as many other Primary Care Trust staff are being made redundant.4 Indeed, despite Department of Health guidance making it clear that public health posts should not be subject to management cuts the BMA has already had to fight hard to counter attempts by PCTs in North West London, 4 Sir David Nicholson reported to the House of Commons Select Committee on 23 November that PCTs had been shedding staff in an “uncontrolled” manner www.gponline.com/News/article/1043440/PCT-redundancies-cost-NHS-40m/ 3 Oxfordshire and Norfolk to include public health positions in the restructuring of their management teams. This is likely to accelerate as more PCTs enter into clustering arrangements. Moreover, it is of particular concern that the Department of Health has only guaranteed to fund regional public health observatories (PHOs) for the first three months of the next financial year. The BMA fears this could create a skills gap before the proposed replacement, Public Health England, is set up. A letter written by DH Director General of Health Improvement and Protection David Harper said‘further funding may become available as business planning continues’. He added that fixed-term contracts at PHOs should not be renewed beyond their notice periods. If there is a significant gap between PHOs winding down and Public Health England being established, a cohort of specialty registrars may have less opportunity to develop advanced skills in health intelligence compared with their predecessors, with a detrimental effect not just for their careers, but for the future health of the nation. Public health structure There is real concern across the public health community that the future structure of the public health service envisioned by the government is fatally flawed. Sending different elements of public health into different organisations, with different cultures and approaches, both to the NHS and each other, could lead to the fragmentation of public health. Therefore, in the BMA’s preferred model, all public health specialist staff would be identified and transferred to a single public health agency, which would be an NHS organisation and which would second them to local authorities. As such, it would include all three domains of public health practice – health protection, health improvement, and public health support for commissioning. This model has much in common with one recently published in the Lancet5 The BMA believes that the creation of this model has several additional benefits. These include: 5 Public health in England: an option for the way forward? Martin McKee et al, The Lancet, 28 February 2011. 4 Public health retaining its independence from political interference, either at a local or national level, but positioned for political engagement; More robust emergency planning and better emergency resilience; Maximising retention and motivation of public health staff by ensuring that organisational and contractual barriers to flexible deployment and career development are removed, through employment on a common contractual basis (retaining current NHS terms and conditions), which will also allow public health to remain an attractive career option for trainees; Co-ordinated training and career progression; and The continued ability of the Health Protection Agency (HPA) to generate income. Currently only half of the HPA’s annual budget of £360m is from the Department of Health. The rest is self-generated through research grants and commercial activity. However, becoming part of the civil service will bar the HPA from these income strands. Since this work, and those doing the work, cannot be separated from other HPA functions, moving the HPA into the civil service will likely lead to significant loss of jobs. The above concerns were reflected in two motions passed at the BMA’s Special Representative Meeting (SRM) on 15 March 2011.6: That this meeting is alarmed that the government’s proposals if implemented will lead to the fragmentation of the specialist public health workforce in England and calls for the creation of a single public health agency in England which shall be an NHS body including all three domains of public health practice – health protection, health improvement, and public health support for commissioning. and That this Meeting believes that, in recognition of the role of health care services in improving health and addressing health inequalities, public health doctors (including Directors of Public Health) should retain the right to remain employed by the NHS under the proposed new public health arrangements 6 On the 15 March 2011 the BMA held a Special Representative Meeting (SRM) to debate the NHS reforms which was attended by several hundred doctors from across the country. For more information on this meeting, including a list of carried motions, see: www.bma.org.uk/healthcare_policy/nhs_white_paper/specialrepresentativemeeting.jsp 5 Public health and local government The BMA has significant reservations about the power that the proposed reforms will enable public health specialists to wield within in local authorities. It is our view that if the vision of the current government is to be realised, there needs to be more than inspirational ideas from Whitehall or guidance from Public Health England. Successfully shifting responsibility for public health delivery to local authorities requires a carefully defined and agreed framework between Whitehall and Town Hall. The major factor for success will rest upon whether the Director of Public Health and the specialist team are able to have control and lead local public health. As such, we welcome Annex A: A vision of the role of the Director of Public Health, and in particular the section on the DPH as principal advisor. However, in order for this vision to be implemented, the DPH needs to be allocated several specific powers and responsibilities. These should includ; the ability to report directly to Chief Executive Officers of local councils and elected officials; the right to full veto over the ring fenced public health budget and be fully accountable to the local population and elected representatives should they fail to deliver measured change in the local public's health. The profession is asking for authority, but it also is prepared to accept responsibility. This is reflected in the below motion, which was passed at the BMA’s SRM on 15 March 2011: That this Meeting calls upon the BMA to negotiate with government to ensure that those filling the role of Director of Public Health within a local authority are:i) professionally independent and free to act as an advocate for the health of their population; ii) properly appointed according to the appointments advisory committee process and registered specialists in public health or public health medicine; iii) given appropriate authority and control over sufficient resources to deliver public health functions effectively; iv) responsible and accountable for the ring-fenced public health budget; 6 v) afforded the status of ‘Executive or Corporate Director’ and able properly to influence all funding streams with public health impacts. Commissioning It is important to note that the scope of public health extends to activities delivered by health care services, including those in general practice and in hospital. Public health has always played a critical role in leading transformational change of health services. In recent years, the financial agenda has become dominant within NHS administration, accompanied by a dilution and diminution of the voice of the healthcare public health workforce. to be reversed. The BMA believes that this marginalisation needs Public health specialists are trained to prioritise evidence for healthcare, to rate its effectiveness and to commission healthcare services based on the health needs of local populations. If the government desires a realisation of its vision to improve the NHS through clinical leadership, the missing link is to be found when public health specialists are working together with GPs and healthcare professionals from all parts of the care pathway to ensure the delivery of appropriate, affordable healthcare of high quality. The role of public health in commissioning is dealt with in more detail in our response to Consultation Question a) below. Evidence Finally, in the foreword to Healthy Lives, Healthy People, the Secretary of State for Health, Andrew Lansley lists the public health problems facing England, including; the highest levels of obesity in Europe; among the worst rates of sexually transmitted diseases; problems from drug and alcohol abuse; smoking and poor mental health. These problems, it is argued, require not only that the government do something, but that it does something “bold” and “new”. This analysis of an unfit for purpose public health system reflects the Secretary of State’s vision of a failing NHS. Yet this view has been rebutted in several academic articles, including two in the British Medical Journal by the King’s Fund’s Chief Economist, John Appleby7. At its SRM the BMA passed the following motion: 7 Does poor health justify NHS reform? BMJ 2011; 2011; 342:d566 & How satisfied are we with the NHS? BMJ 2011; 342:d1836, John Appleby 7 That this Meeting deplores the government’s use of misleading and inaccurate information to denigrate the NHS, and to justify the Health and Social Care Bill reforms, and believes that:i) the Health Bill is likely to worsen health outcomes as a result of fragmentation and competition; ii) the NHS needs to respond to the challenges presented by altered patient demographics, and by development of medical technology and medical care provision; iii) the NHS needs national planned and coordinated strategies and frameworks to improve health outcomes. Whilst there is evidence that the NHS is working well8, there is less evidence on the performance of public health medicine. However, the BMA does not believe that this means public health as a specialty is failing, but that it instead reflects the difficulty in gathering evidence on the influence of public health interventions. There are several reasons for this. First of all, it is too simplistic to say that public health as a medical specialty is failing because, for example, health inequalities are increasing. Health inequalities are the result of myriad influences outwith the health sphere, not least socio-economic decisions made by government. What the evidence does illustrate is that the health of the poorest in society continues to improve and has done so over the last decade but the health of the wealthiest in society has also increased over the same period. 9 We would also contend that the numerous reorganisations of public health have proved to be disruptive. Each one has resulted in a loss of specialist expertise from the workforce, impacted negatively on corporate memory and failed to afford public health delivery equivalent importance to that given to other parts of the healthcare service. Public Health delivery will benefit from the setting up of a robust, sustainable public health service that is independent of political direction and which is placed to act in response to the population needs that it identifies through appropriate surveillance of the state of the population’s health. We fervently hope that the model which emerges from the current restructuring will be one which endures for many years. This will allow public health as a specialty time to carry out the necessary and long-term work of improving the health of the nation. 8 Does poor health justify NHS reform? ibid Fair Society, Healthy Lives: The Marmot Review, Figure 2.1 Life expectancy at birth by social class, a) males and b) females, England and Wales, 1972–2005 9 8 9 Consultation Questions: The BMA welcomes the opportunity to respond in detail to the five consultation questions raised in Healthy Lives, Healthy People. (a) Role of GPs and GP practices in public health: Are there additional ways in which we can ensure that GPs and GP practices will continue to play a key role in areas for which Public Health England will take responsibility? It is important to recognise the role that GPs already play in delivering public health improvements, as well as noting the external factors that can constrain this work. These include pressures on GPs (such as time limitations and unreasonable levels of documentation); the difficulty in finding appropriate help and support and the fact that initiatives are often not sustained. If the public health role of GPs and GP practice is to be developed, the work needs to be focused, evidence based and well-resourced. The relationship between GPs and public health, and in particular those practising health care public health (HCPH), is crucial in the development of these services. There is an urgent need to maintain the numbers of HCPH specialists and this can only be done after a careful consideration of where they are to be based. This is one of the reasons that so many people are concerned about the almost total absence of reference to public health support for commissioning (or health care public health) in either Liberating the NHS or Healthy Lives, Healthy People. Due to this lack of reference, and because it is the least understood of the three domains of public health, this section will first give an explanation of what health care public health is. It will then go on to discuss its role in GP commissioning, how active GPs can be effective commissioners and, finally, where HCPH specialists should be based. What is Health Care Public Health? Health care public health describes a set of public health skills acquired as part of specialist public health training and practised by members of 10 the public health specialty who are involved with the commissioning of health care services. Core competencies for HCPH include: Assessing health needs of populations, and how they can best be met using evidence-based interventions; Supporting commissioners in developing evidence based care pathways, service specifications and quality indicators; Providing a legitimate context for setting priorities using ‘comparative effectiveness’ approaches and public engagement. These competencies are needed in order to sustain health services within a cash-limited system. A further role which can fall to HCPH is that of engagement with the public over service development and in particular over the prioritisation of services. HCPH is ideally placed to undertake this function because it relates to populations and not individuals and therefore is free of conflicts of interest in relation to individual patients or treatments. This function is not just about conveying to patients in lay terms the relative benefits of treatments or groups of treatments for particular conditions. Crucially, this function must also deal with the issues of the relative importance of treatment for different conditions or groups of patients within an overall cash-limited system. This role of HCPH as honest broker will be key to protecting the ability of general practitioners and hospital specialists to continue to act, and to be seen to act, in the best interests of their individual patients. Government has offered the medical profession the opportunity to take greater control of health services, inviting general medical practitioners to lead the commissioning process. For this approach to succeed and so secure the future of the NHS, the BMA believes that it is essential that the key role of the specialist in health care public health is clearly understood by all NHS staff and by government, and proper provision made for its place in support of GP commissioning. Health care public health and GP commissioning Commissioning aims to ensure that available resources secure the right technologies, in the right places, to provide as much health improvement and health care as possible. This occurs within an ever changing 11 environment as health needs change, new technologies and/or evidence of effectiveness become available and the amount of funding fluctuates. In general medical practice, the doctor has responsibility for mobilising appropriate local health resources in support of the needs of their patients. Consequently, GPs are in a strong position to understand the needs of their own patients. Yet, this view, derived from their own day- to-day practice, is only one aspect of a strategic view. Within the general practice community, even within a locality or community, there will be many GPs, each with a unique view. The role of the health care public health workforce is to assist general practice commissioners in synthesising their individual view of health needs into a position that can be used to drive commissioning on behalf of their consortia’s registered population. Successful criteria for commissioning include: 1. The ability to command support when making choices about the allocation of resources; 2. Balancing resource allocation decisions across the whole of the healthcare portfolio for both existing and new services; 3. Minimise unnecessary health care interventions and use of poor value interventions; 4. Setting out specifications and standards for services that will achieve the clinical, quality and productivity outcomes sought and securing these through the contracting process; 5. Monitoring services to ensure delivery of these outcomes; 6. Developing and improving the care pathway for patients to better achieve desired outcomes. Underpinning these are the transactional aspects of commissioning. Having decided ‘what we need’ and ‘how much we need’ and ‘with what resource’ and ‘to what standard’ there are elements of commissioning concerned with the contracting and procurement that govern ‘from whom’, ‘at what cost’, and ‘how to measure the results.’ The contracting and procurement aspects of the commissioning cycle need to be undertaken in consultation with commissioners and public health specialists, but not directly by those groups. The delivery of successful commissioning is a team undertaking. This team includes information scientists, experts in systems change, public 12 engagement and communications specialists and project managers as well as HCPH. This paper focuses on the contribution of HCPH that can: 1. Summarise the evidence setting out the relative value of different interventions; 2. Set out the contribution that interventions make to defined outcomes and the relative return of investment across portfolio of commissioned services; 3. Identify areas for disinvestments; 4. Design monitoring and evaluation frameworks, collect and interpret results; 5. Support the development of care pathways to improve patient outcomes. Effective GP commissioning by GPs General Practitioner commissioners acting on behalf of their colleagues and peers and the patients registered to a consortia will also remain providers of primary care. It is inevitable that, from time to time, dilemmas will arise between the GP as provider of care and the GP as commissioner of care. A mechanism is required to deal with these dilemmas. We propose that the incorporation within commissioning process of public health specialists operating in the field of health care public health provides the route to resolve these issues. HCPH specialists operate as ‘population doctors’ whose work is founded on explicit utilitarian principles: the greatest good for the greatest number. HCPH specialists operate by using information to examine the health needs of a population and develop diagnostic hypotheses, undertaking relevant investigations which seek to test these hypotheses and then formulating appropriate responses based on expert knowledge drawn from a range of sources, including that of local experts in primary and secondary care. They offer independence and objectivity on individual cases, because they work at population level. HCPH specialist workforce is an essential ingredient in securing excellence in GP commissioning. This workforce has undergone specialist training and plays a critical role in the specifying and sourcing of data and the analysis and interpretation of that data to create intelligence to inform commissioning. Data without interpretation remains statistics. Health care commissioning based exclusively on data will always be passive. Health care commissioning based on expertly crafted intelligence will lead 13 to active commissioning, able to define, to pursue and to achieve sought after objectives. Alongside the public health specialist workforce there is a need to imbue public health skills in two other key groups. For general practitioner commissioners there is a need to provide a set of public health skills that enables this group to understand the benefits and limitations of a population approach. Developing this skill set would enable GP commissioners to undertake some public health tasks themselves. More importantly, it would also furnish such commissioners with an ability to understand when it was appropriate to make referrals of issues to public health specialists, and to frame issues in public health terms. It would also enable GP commissioners to assess critically the quality of product provided by public health specialists and facilitate shared ownership of emerging decisions informed by public health input. For secondary and tertiary specialists, usually employed as consultants in hospital specialties, there is scope for the re-emergence of the clinical epidemiologist. This group comprises specialist clinicians who in addition to their primary specialty, are also trained in specialist aspects of public health medicine. Equipping a group with such skills enables them to contribute a specialist clinical perspective informed by a population approach and is essential in developing whole systems of care that span all healthcare sectors. Where should health care public health specialists be based? The government plans to relocate the vast majority of the public health workforce in England to homes within Public Health England (PHE) and local authorities. It is clear that public health is about improving health outcomes and that much of this work has to focus on tackling the wider determinants of health. The government has also mapped out a process to migrate the Health Protection Agency into the proposed national Public Health Service. Although this strategy has much to commend it, it endangers the HCPH function that has developed within the local NHS environment since 1974. There is a compelling argument that health care public health needs to be retained within the NHS, as part of the commissioning function of the reformed NHS. We believe that GP consortia need to have ready access to HCPH, along with other skilled support staff. At present there are about 14 250 public health physicians across England. This dedicated specialist workforce is augmented by a larger number of public health specialists currently working in commissioning organisations and who incorporate elements of health care public health within jobs that also include health protection and health improvement roles. There is a need to employ this workforce in a manner that preserves its utility and provides cohesion and continuity. We do not believe that local authorities will see the support of health care commissioning by GP consortia as part of local authority business, and accordingly we would counsel that the health care public health workforce requires an alternative home that secures its expertise within the NHS family. Employment of the HCPH specialist workforce could be secured within the NHS in a number of ways. These include: Transfer of those currently working in specialised commissioning into the National Commissioning Board; Transfer of health care public health specialists into Public Health England and contracting services back to commissioning consortia; Transfer of HCPH physicians into the larger GP consortia; Transfer of HCPH physicians into host GP consortia, to work across a sub-national area; Transfer of HCPH into a host local authority to contract services back to commissioning consortia; Transfer of HCPH physicians into universities on honorary NHS contracts, with rolling contracts for provision of GP commissioning support. HCPH will best be organised to deliver a critical mass of expertise that provides resilience in the face of organisational evolution; that offers an ability to cope with a wide range of demands and to avoid duplication of work in relation to appraising evidence for clinical services and models of care; and yet is situated sufficiently locally to develop the working relationships needed to be a trusted source of both informally and formally commissioned advice. In practice, this will mean locating HCPH at a level larger than local authority (to obtain critical mass) but more local than current regional structures to relate effectively to consortia and local authorities and to enable responsiveness to local demands. This could be incorporated into the proposed national Public Health Service, thus preserving all three domains of public health within that service. 15 Our clear preference would be for options which maximise the co-location of specialists in all three domains of public health. This is important to ensure the critical mass of specialist workforce and to maximise the cooperation across all three domains of public health in optimising population health. It is currently envisaged that specialist public health trainees will be placed within the national public health service and seconded to other public health settings in order to obtain the experience and develop the competencies required for specialist practice. Of necessity, this will require trainees to work across Local Authority, NHS and university environments. The career option for doctors wishing to work to improve health services would remain, with the continuation of the role of the public health physician. 16 Public Health Evidence: General Comments The BMA welcomes the opportunity to further strengthen the intelligence functions of public health. We are reassured by statements from the Department of Health Equality Delivery System team that health data will include monitoring all six strands of diversity10, as a core requirement of all NHS Commissioned Services. This is fundamental to delivering the NHS Charter commitment to equity and equality and without this level of evidence there is a risk that the NHS will remain opaque about discrimination in delivery of services. In order for this evidence to be of any use there will need to be adequate capacity to analyse the information and present it in an accessible and appropriate manner. This reinforces the need for a national hub for minority public health - similar to units in the US and New Zealand11. We would also suggest that every NHS commissioned service is asked to publish their annual performance for the six legal strands, for key indicators including mortality, readmissions and length of stay. Wider partners can contribute to this by implementing similar frameworks for recording data and through joint strategic needs assessments. (b) Public health evidence: What are the best opportunities to develop and enhance the availability, accessibility and utility of public health information and intelligence? Of primary importance is the need for Public Health England (PHE), in which ever form it takes, and the National Institute of Health Research (NIHR) to develop clear quality standards to which providers of public health evidence and information would have to adhere. These standards must relate to both the completeness of the evidence and the validity of the information. Many of the examples of good practice that have been shared (through, for example, Strategic Health Authorities or Darzi Programme boards) have been insufficiently detailed on a number of areas. In 10 The six strands of diversity are age, disability, gender, race, religion or belief and sexual orientation. 11 For more information on the US Model can be viewed please visit: http://minorityhealth.hhs.gov/ Further details on the New Zealand Model can be seen here: www.moh.govt.nz/moh.nsf/pagesma/321 17 particular, the exact population for whom the flagship intervention or programme was intended; the previous level of service; and, on which outcomes were measured and over what time. Secondly, there also needs to be specific consideration given to the fact that the intended audience of much of this evidence will be local authority elected members , who do not have detailed knowledge of, or training in, public health. It should be clear from the title of these documents that they are tailored specifically for the consideration of the member with responsibility for health. In order to achieve this, appropriate language and lay explanation of health terms must be given (with which public health doctors can help). Any briefing to elected members must also be must be backed up by a scientific briefing document, with references, that public health doctors can use to facilitate further local discussion. There are a number of concerns that placing public health within the local authority will interfere with the ability of the Director of Public Health and their team to have access to NHS derived information on the health of populations and the local and national patterns of use of health care and outcomes from health care use. These are not trivial matters, since public health practice is based on the scientific discipline of epidemiology, and without access to relevant and timely data public health teams will not be able to function effectively. Public health specialists within both Primary Care Trusts and Universities should work in and with Public Health England to help the setting of quality standards for evidence and the quality standards for scientific briefing documents. (c) Public health evidence: How can Public Health England address current gaps such as using the insights of behavioural science, tackling wider determinants of health, achieving cost effectiveness, and tackling inequalities? First of all, there must be a transparent process through which research funding is prioritised, which takes into account criteria such as prevalence of the risk factor and severity of the resulting ill health. For the sake of credibility and rigour, the BMA believes that a University that 18 has experience in the science of decision making should run the process. The London School of Economics (LSE) and Universities of Cranfield, Warwick and East Anglia all have experience in recognised methods. We do not believe that accountancy firms, management consultancies or other private sector organisations are suitable candidates for carrying out this work. Secondly, it is likely that PHE will be the organisation best placed to have a global view of the current state of research in each of the risk factors, diseases and populations. Special attention should be paid to the study type. For example, if there have been six reported uncontrolled pilots of a particular public health intervention, then clearly it would make less sense to commission a seventh uncontrolled pilot, but instead commission a controlled pilot. The BMA believes that only this transparent and organised approach will result in the public health community having the ability to answer the question, ‘What is the next most pressing research priority in our field?’ 19 (d) What can wider partners nationally and locally contribute to improving the use of evidence in public health? The BMA believes that there is a role for wider partners to make a contribution to improving the use of evidence in public health. This includes having a transparent input into both prioritising research funding and into developing the research question itself. Whilst ‘Do breastfeeding classes increase the chances of mothers’ breastfeeding babies for six months?’ is a valid research question, a more pertinent research question also will take into account the current circumstances. In this instance, the question needs to take into account the existence of SureStart centres and responsibility of Local Authority to their resident population. A more focused research question would be ‘Do breastfeeding classes in Surestart centres improve the proportion of mothers within a Local Authority who breastfeed for six months?’ Moreover, much of current research only looks at improvements in outcomes for those attending available services. To be truly useful to a local authority, research must be undertaken at population level, with outcomes measured from samples or records taken from the whole population including those who do not attend services. Finally, much as in the answer to Consultation Question (b), it is vital that results should be tailored and disseminated as audience-specific briefings - both for elected members and the public health doctors - with the latter containing the technical detail including references and supporting data. 20 e. Regulation of public health professionals: We would welcome views on Dr Gabriel Scally’s report. If we were to pursue voluntary registration, which organisation would be best suited to provide a system of voluntary regulation for public health specialists? We fully support the recommendations in Dr Scally’s report that all public health specialists are subject to a robust system of statutory professional regulation and that the Health Professions Council (HPC) should regulate public health specialists as an additional profession. We also support the recommendation that there is no substantial change in the roles of the General Medical Council, the General Dental Council and the Nursing and Midwifery Council in respect of public health. The BMA calls for the statutory regulation of all public health specialists in line with doctors’ statutory regulation. We categorically reject the government’s expressed wish to pursue the voluntarily registration of non-medical public health specialists. There are several reasons for this. The most important is the safety of the public at large. Not to expect non-medical public health specialists to be statutorily regulated, whilst at the same time demanding that professions such as chiropodists and arts therapists are, fails to appreciate the significant role that public health specialists can have in shaping the health of an entire population. Public health professionals make substantial and fundamental decisions about the health and well-being of the population. Like drug therapies, decisions and interventions made by public health specialists can have intended beneficial effects. However, mistakes and misconduct by public health professionals can have serious adverse and long lasting impacts, potentially most importantly in emergency events and threats such as pandemic flu. Whilst doctors in public health medicine are held up to medical professional standards through the GMC, and some health professions such as nurses have similar regulatory bodies, it is important that all public health professionals are held up to the highest professional standards because of the gravity and importance of public health advice. Another reason for the statutory regulation of all public health specialists is public opinion. In his letter to the Chief Medical Officer, Dame Sally Davies, which opens his report, Dr Scally states that “Central to the role of professionals in this modern age is the necessity of establishing and maintaining the respect of the public.” This is 21 particularly true in an occupation that spends much of its time proffering lifestyle advice. The role and title of “doctor” is already well understood and respected, with the general public maintaining a trust of doctors not seen in other professions, 12. It is unlikely that the public would be as willing to listen to the advice, or respect the decisions, of someone who they knew not be professionally regulated. For this reason, amongst others, failing to regulate non-medical public health specialists also undermines the work undertaken across public health to establish parity between medical (doctors) and non-medical (other professional backgrounds) specialists. Several years ago the Faculty of Public Health established parity in training and appointments between medical and non-medical specialists for public health and expanded the job description of consultants to encompass non-medical consultants. The BMA believes that public health is strengthened by the diversity and breadth of these backgrounds and that this model establishes a rounded framework that is more robust for this inclusive approach. However, the equality of training and appointment is undermined by the inequality around regulation. Such an approach, since it holds doctors to a higher standard than their non-medical colleagues, is unfair both to doctors (since it demands of them something not asked of their non-medical colleagues) and to non-doctors (since it suggests to them that their experience and qualifications still do not make them equivalent to their medical colleagues). We therefore believe that statutory regulation is vital to protect the public; to ensure their continued confidence in the decisions the specialty makes on their behalf; and, to maintain and advance the unity of public health as a specialty. March 2011 12 92% of British adults aged 15+ say they would generally trust their doctor to tell the truth - Annual Survey of Public Trust in Professions, MORI on behalf of the Royal College of Physicians (RCP). (2009) 22 Appendix The table below is a summary of the BMA’s Board of Science’s work and subsequent recommendations on the topics covered in Healthy Lives, Healthy People. Health Lives Health People Inequalities At the 2010 Annual Representative Meeting (ARM)13, the BMA in health endorsed the Marmot Review and strongly urged government to: (i) take forward the recommendation that expenditure on preventative services increase; (ii) increase the proportion of overall expenditure allocated to the early years to give every child the best start in life; (iii) set a 'minimum income for healthy living'; (iv) adopt fiscal policies to narrow the income gap between our poorest and richest citizens. Following the publication of Fair Society, Healthy Lives: A Strategic Review of Health Inequalities in England (the Marmot Review) in February 2010, the BMA has undertaken a programme of work to consider the role of doctors in addressing the social determinants of health inequalities. In October 2010, the BMA hosted a breakfast debate on health inequalities which was chaired by Dr Hamish Meldrum (Chairman of BMA Council) and included Rt Hon Andrew Lansley CBE MP (Secretary of State for Health), Professor Sir Michael Marmot (BMA President) and Professor Sir Ian Gilmore (Immediate Past President, Royal College of Physicians) as guest speakers. The debate provided an opportunity to hear the government's response to issues over health inequalities and the NHS white paper. On 4 November 2010, BMA President Sir Michael Marmot hosted a roundtable meeting and dinner with representatives from the medical Royal Colleges and other key stakeholders to discuss ideas on how each organisation will encourage and support the development of policies and activities to address 13 23 the social determinants of health. The BMA hosted a conference on the 10 February 2011 to celebrate the one year anniversary of the publication of Fair Society, Healthy Lives. This explored ways in which the social determinants of health can be addressed through local action, in particular how the medical profession can support this. Section 3.5 – 3.12 Starting well Breastfeeding The 2009 BMA Board of Science report Early life nutrition and life long health highlights the importance of breastfeeding and raises concerns about the need to increase breastfeeding rates in the UK – including addressing the inequalities in breastfeeding between socio-economic groupings. The report concluded that breast milk is the ideal food for babies in their first few months. Mothers need support in order to breastfeed successfully. There is consistent evidence of better childhood cognitive development, and a lower risk of several disease outcomes including obesity and diabetes, in children and adults who were breastfed rather than formula-fed. Section 3.13 – 3.28 Developing well Personal, The BMA has long supported the strengthening of sex and social and relationships education (SRE) in schools, and the Board of health Science has published a number of reports in this area education including Adolescent health (2003), Sexually transmitted infections (2002) (the Board of Science produced an update to this report in 2008 ) and School sex education: good practice and policy (1997). The implementation of well-designed SRE programmes in schools is an important measure in reducing teenage pregnancy rates, delaying the onset of sexual activity, and increasing access 24 to contraception and sexual health services. The need for an effective school-based programme was reaffirmed at the BMA’s 2008 ARM where members called for SRE to be delivered to a nationally standardised curriculum by specialist SRE Teenage teachers, beginning at primary school entry. pregnancy The BMA supports measures to reduce teenage pregnancy rates in the UK. As highlighted in the 2003 BMA Board of Science report Adolescent health, teenage pregnancy can adversely impact on the health, educational opportunities and social development of the parent and the child. Rates of teenage pregnancy in the UK remain the highest in western Europe. The BMA believes that greater emphasis is therefore needed on the Change4Life prevention of teenage pregnancy in the UK. Any teenage pregnancy strategy should also be supported by broader strategies aimed at reducing socioeconomic deprivation and Improving inequalities. diet and nutrition, and promoting The BMA signed up as a partner to the Change4Life campaign in physical November 2008. activity As highlighted in the 2005 BMA Board of Science report Preventing childhood obesity, there has been an alarming rise in the levels of obesity among children in the UK and more recent predictions anticipate this trend to continue. The BMA believes there is an urgent need to take action to create an environment that supports and sustains healthy eating and physical activity. This requires a comprehensive, long-term strategy that encourages healthy choices through action in the following areas. The BMA believes the UK Governments should: ensure that the food and drink industry implement a standardised, consistent approach to food labelling based upon the traffic-light front-of-pack labelling. This should also include Guideline Daily Amount (GDA) information 25 legislate for a ban on the advertising of unhealthy foodstuffs, including inappropriate sponsorship programmes, targeted at school children make more extensive use of the media, including children’s programming, to promote healthy lifestyle messages that make such lifestyles both fun and aspirational introduce a legal obligation to reduce salt, sugar and fat in pre-prepared meals ensure that adequate funding for healthy school meals is ring-fenced from the education budgets of schools and education authorities subsidise the cost of fruit and vegetables to encourage healthy eating ensure funding to establish and sustain training programmes for those who are involved in the care of children with obesity promote the importance of fetal and early life nutrition and its relationship to lifelong health Accidental death and injury provide education and support that promotes breast feeding and the impact of breast feeding for the health of mothers and babies develop a strategy to encourage children and young people to take part in regular exercise increase and protect access to recreational facilities (eg public swimming pools and playing fields) regardless of socio-economic status and level of physical and psychological ability promote active travel networks by providing safe environments for pedestrians and cyclists and ensuring that there is appropriate support of the built environment by local and central government increase the provision of facilities for the combination of cycling with rail and other travel As highlighted in the 2009 BMA Board of Science briefing Transport and health, taking action to promote healthy eating and physical activity will have substantial cobenefits for the environment and in tackling climate change. Policies that promote safe, affordable and accessible use of 26 active transport, for example, will reduce dependence on car use, thereby improving road safety, air quality, and increasing physical activity levels. The 2001 BMA Board of Science report Injury prevention focuses on people in all age groups and the burden of mortality and morbidity due to injuries from any cause. The report highlights the need for injury prevention to be recognised as a major public health problem as it carries one of the highest costs in both human and economic terms. The report made the following recommendations: Injury surveillance: Injury surveillance centres should be established in each UK home country with a remit to collate, interpret, add value to, and disseminate injury statistics across relevant stakeholders; these surveillance centres should also have a remit for research and development of new methods of surveillance of injuries and injury risk prevalence. The concept of ‘injury’ rather than ‘accidents’ should be recognised by the Department of Health and the NHS. The definition of injury and methods of recording data nationally require a consensus from all stakeholders to include hospital departments, police road traffic accident reports, fire services, the Health and Safety Executive, and others. The health sector should adopt a primary role in the collection of high quality data on injuries and their consequences. A comprehensive injury surveillance system should include data from surveys (especially of vulnerable groups) of exposure to known avoidable hazards (eg dwellings without functioning smoke alarms, child pedestrian exposure to nontraffic calmed roads) and of the population at risk of specific injuries (eg kilometres cycled per person). Injury surveillance should include an account of the population prevalence of injury disability. Future national 27 sample surveys of morbidity and disability should clearly identify those cases attributable to injury (preferably linked to detail of the original injury event). Existing data systems concerning injury maintained by separate agencies should be enhanced and co ordinated. The accident and emergency minimum data set should be made mandatory and be consolidated into an accessible national database. Data collection in primary health care should also provide an important subset of the overall picture since minor injuries frequently present in general practice settings as well as accident and emergency units. The national sample system of accident and emergency attenders with home and leisure injuries run by the Department of Trade and Industry (HASS/LASS) should be extended to cover all injury types regardless of circumstances or intent. National data concerning road traffic accidents (STATS 19) collated by the Department of the Environment, Transport and the Regions should be developed to include a standardised definition of injury severity and be linked to accident and emergency departments. Data from coroners’ inquest reports relating to injury should be compiled into an anonymous standardized national database. Each of these injury surveillance systems should include coding of injury circumstances using ICD cause codes and a measure of injury severity using the injury severity score. Consideration should be given by the government to placing a levy on insurance companies to fund research into accident prevention and interventions, and for insurance companies to provide mandatory anonymised reports about all personal injury claims in order to assist in injury surveillance. Investigations should be conducted to ascertain how this can be successfully achieved and implemented as policy. 28 Research and development The total research spending on injury should be increased to a level commensurate with other major public health problems and positive discrimination should be exercised to balance the lack of charitable and private resourcing. A comprehensive, public, and fully costed account should be kept of all research on injury (public and private/voluntary funded). Systematic efforts are needed to improve the evidence base for effective injury prevention, especially for neglected areas such as intentional injury, sports injury and falls, and to ensure that any widely implemented injury prevention actions for which there is no current evidence of effect are subject to urgent formal trials. New research strategies are needed to: o extend the evidence base for effective injury prevention to include details of cost-effectiveness o understand and reverse social inequality in injury risk o develop a national plan for multi-disciplinary injury prevention research including research councils, government departments and other major research funders There should be several multi-disciplinary injury research centres based in UK universities, covering between them the full range of injury by age group, intent and injury phase from prevention through to rehabilitation. The work of, and data emanating from, the present and former public research laboratories (health and safety, transport research, fire research, building research) should be linked to multi-disciplinary injury research centres. Violence and Implementation and strategic policy development abuse Co-ordinated multi-sectoral action should be focused on the full implementation of those few injury prevention methods 29 for which there is strong evidence of effect (eg car occupant restraints, traffic calming, road speed limit enforcement, smoke alarms, and child proof closures). Further effort is needed to identify and eradicate avoidable mortality and morbidity due to inadequacies in trauma management. A programme budget should be developed to describe the extent of public investment in safety and injury prevention for comparison with other major public health programmes and for audit against cost-effective best practice. The NHS should increase its commitment to health impact assessment and to enforcing health and safety legislation, especially by: o encouraging systems for managing health at work. o developing occupational health services and competencies. o improving data on occupational disease and injury. o promoting health and safety in the workplace. An accurate account should be created of the burden of injury versus other major public health threats in the UK using internationally recognised methods such as Disability Adjusted Life Years (DALYs). The four UK health administrations should jointly review and compare the resources and priorities that they give to injury prevention, and identify any specific approaches that have been shown to be effective. A national agency should be established in each of the four home countries following a process of consultation and review with all interested stakeholders with the following remit: o establish a single over-arching national body for injury prevention and control working in partnership across government departments. o co-ordinate initiatives across all forms of injury, age groups o be responsible for establishing national injury 30 surveillance systems o commission several multi-disciplinary academic research centres o develop a national strategic plan for injury prevention o be answerable to a single responsible government minister At the 2009 ARM BMA members highlighted the need for greater awareness of violence prevention among the medical profession. In response to this, the Board of Science produced a web resource, Violence and Health. This signposting provides doctors with an overview of the nature of violence and outlines how the medical profession can help prevent violence from occurring. The 2007 BMA Board of Science report Domestic Abuse Domestic Abuse aims to raise awareness of domestic abuse as a healthcare concern and makes the following recommendations: Healthcare professionals Addressing domestic abuse in the healthcare setting is a priority. In order to achieve this, all healthcare professionals should: o receive training on domestic abuse. This needs to be implemented on a national scale within emergency medicine o take a consistent approach to the referral of patients to specialist domestic abuse services o Mental health ensure that they ask patients appropriate questions in a sensitive and non-threatening manner in order to encourage disclosure of abusive experiences o give the clear message that domestic abuse is unacceptable and not the victim’s fault, and that there are specialist support services which can provide information, advice and support o recognise that men can also be victims of domestic abuse and should therefore be questioned if domestic abuse is suspected. The UK governments 31 The UK governments should: o raise general awareness of domestic abuse, including for example its prevalence, manifestation and available support services for victims o ensure strategies to address domestic abuse are explicitly highlighted in their public health strategies o develop a more structured and statutory basis for addressing domestic abuse at the local level in a similar manner to the policies in existence for child protection o recognise that men are also victims of domestic abuse and this needs to be taken into consideration when developing policy to address this concern o work to identify and combat the barriers to reporting incidents of domestic abuse. This should help identify the true prevalence of domestic abuse. The rights afforded to transgender individuals by the Gender Recognition Act 2004 should be proactively implemented, for example refuges must be more accessible to transgender individuals. Further work is required in order to: o ensure that information about support services is readily available in healthcare settings such as GP surgeries, A&E units and maternity departments o raise awareness of the scale of domestic abuse in the LGBT community o break down the barriers for such individuals to access the services and protection they need o empower victims to report the abuse to the police. Domestic abuse education programmes should be implemented in all primary and secondary schools. Research There already exists a good research base on domestic abuse, in particular with regard to female victims. Further research is needed on: Tobacco o prevalence of elder abuse 32 control o domestic abuse within ethnic minority groups o the experience of disabled men who are victims of domestic abuse o pregnant victims of domestic abuse o the implementation and effect of the RCOP guidelines on the routine enquiry of female patients in obstetrics and gynaecological healthcare settings o the number of refuges which exist for male victims o the effectiveness of interventions after disclosure of abuse to healthcare professionals o system level changes in healthcare settings that improve the response of healthcare professionals to survivors of domestic abuse o prevalence and experiences of gay male victims of domestic abuse o prevalence and experience of transgender victims of domestic abuse o effective treatment and interventions for perpetrators of domestic abuse. The 2006 BMA Board of Science report Child and adolescent mental health: A guide for healthcare professionals examines the type of problems faced by children and young people aged five to 17 years and the prevalence of mental health problems among this age group. The report discusses barriers to the necessary provision of treatment, including stigma and discrimination, and makes the following recommendations for actions: o government policies and strategies must be fully monitored, and data collected and analysed to ensure that they are effective and addressing need. This information should be made publicly available and accessible o the government must address the shortage of mental healthcare professionals o there must be adequate funding for child and adolescent mental health services (CAMHS) to ensure that they are properly resourced and staffed o innovative services are needed to meet the needs of young people, and access to such services must be improved 33 o it is essential that all professionals providing CAMHS receive adequate training and support enabling them to work effectively together o the provision of appropriate mental health services to 16 and 17 year olds must be improved o collaboration between CAMHS and AMHS must continue and improve to ensure a smooth transition to adult services o the provision of mental health services to looked after children and young people must be improved o the inadequacy of mental health services for children and young people with learning disabilities must be addressed o inequalities in mental healthcare experienced by BME groups must be tackled o barriers to receiving healthcare faced by asylum seeker and refugee children must be addressed o actions must be taken to improve access to mental health services in young offender institutions, and to tackle the high rate of suicide among young offenders o there is a need to improve public knowledge and understanding of mental health o there should be better provision and dissemination of information about mental health aimed at children and young people, appropriate to different age ranges o the media should be encouraged to show those with mental health problems in a positive light, including children and young people o there is a need for more and better mental health promotion to BME groups in order to address health inequalities o current strategies to address stigma and discrimination against those with mental health problems must be fully implemented The BMA supports the findings of the cross-government mental Alcohol health outcomes strategy, "No health without mental health” that mental health is given the same priority as physical health and believes that this is a major positive philosophical shift. In order to help support this report, the BMA believes that any public health local data collection/local priorities should be aligned. 34 The BMA Board of Science has published several reports on tobacco control including Forever cool: the influence of smoking imagery on young people (2008), Breaking the cycle of children’s exposure to tobacco smoke (2007), and reproductive life Smoking and (2004). Tobacco control requires a wide range of behaviour change policies. The types of policy will depend on the current levels of awareness of harms, social norms and the willingness to accept more coercive measures. While tobacco control policies in the UK are among the most comprehensive in Europe, more than one in five adults still smoke, and many people are continuing to take up the habit. The downward trend in smoking prevalence has also slowed in recent years. Experiences in other countries suggest that if we do not sustain and strengthen current tobacco control policies, smoking prevalence will not only stop declining but could even start increasing again. The BMA believes the UK Governments should aim to make the UK tobacco free by 2035. This ambitious target requires a comprehensive, adequately funded tobacco control strategy focusing on tough and progressive measures to reduce the demand for, and supply of, tobacco products. This requires us to action the following areas: Reducing demand for tobacco products The UK Governments should: o prohibit the display of tobacco products at the point-ofsale o mandate plain packaging for all tobacco products, restricting information on the packet to the name of the cigarette brand, health warnings and any other mandatory consumer information o introduce minimum pricing for tobacco products o ensure that taxation on all tobacco products is standardised and increased at higher than inflation rates 35 Limiting supply to children and young people The UK Governments should: o prohibit the sale of packs of ten cigarettes o prohibit the sale of tobacco products from vending machines o reduce the number of outlets selling tobacco through the introduction of a system of positive licensing, as is the case for selling alcohol Educational campaigns and pro-health imagery The UK Governments should: o implement further country-wide media campaigns to inform the public about the health effects of exposure to secondhand smoke at home and in vehicles o implement mass media, population-wide communications campaigns promoting antismoking messages and imagery o ensure action to limit pro-smoking imagery in the entertainment media through: the implementation of programmes aimed at informing those involved in the production of entertainment media of the potential damage done by the depiction of smoking legislation to ensure that all films and television programmes which portray positive images of smoking are preceded by an anti-smoking advertisement greater consideration of pro-smoking content for thde classification of films, videos and digital material Supporting smokers to quit The UK Governments should: o ensure smoking cessation services are targeted at high risk groups (lower socioeconomic groups, pregnant mothers, those with mental health problems and children who are looked after by the state, in foster care or in institutional settings) o provide adequate funding for smoking cessation services, including using two per cent of the revenues raised from tobacco tax o ensure smoking cessation products are available in all 36 the places where tobacco products are currently sold o encourage employers to provide access to cessation services Helping those who cannot quit The BMA’s Board of Science supports a tobacco-free harm reduction strategy as part of a structured approach leading to permanent smoking cessation. Harm reduction should therefore only be considered as an interim measure for those individuals who are struggling to quit, with cessation still being the ultimate goal. The Board of Science has published a number of reports with evidence-based recommendations for action including Under the influence: the damaging effect of alcohol marketing on young people (2009) and Alcohol misuse: tackling the UK epidemic (2008). The BMA believes a comprehensive, evidence-based alcohol control strategy is required with action in the following areas: Restricting access to alcohol The UK Governments should: o increase and rationalise taxation to ensure it is proportional to alcoholic content o reduce licensing hours for both on- and off-licensed premises o ensure town planning and licensing authorities consider the local density of on-licensed premises and surrounding infrastructure when evaluating any planning or licensing application Responsible retailing and industry practices o The UK Governments should: o ensure licensing legislation is strictly enforced, including the use of penalties for breach of licence, suspension or removal of licences, the use of test 37 purchases to monitor underage sales, and restrictions on individuals with a history of alcohol-related crime or disorder o provide adequate funding for enforcement agencies, with consideration given to the establishment of a dedicated alcohol licensing and inspection service o introduce legislation to prevent irresponsible promotional activities in on- and off- licenses as well as the establishment for minimum price levels for the sale of alcohol o introduce legislation to establish minimum price levels for the sale of alcohol o commission further independent research and evaluation of sales practices, covering all aspects of industry marketing o introduce and rigorously enforce a comprehensive ban on all alcohol marketing communications Alcohol education and health promotion The UK Governments should: o commission further qualitative research examining attitudes towards alcohol use in the UK o ensure public and school-based alcohol educational programmes are only used as part of a wider alcoholrelated harm reduction strategy to support policies that have been shown to be effective at altering drinking behaviour, to raise awareness of the adverse effects of alcohol use, and to promote public support for comprehensive alcohol control measures o make it a legal requirement to prominently display a common standard label on all alcoholic products that clearly states: alcohol content in units recommended daily UK guidelines for alcohol consumption a warning message advising that exceeding these guidelines may cause the individual and others harm o Make it a legal requirement for retailers to prominently display at all points where alcoholic products are for 38 sale: information on recommended daily UK guidelines for alcohol consumption a warning message advising that exceeding these guidelines may cause the individual and others harm o introduce a compulsory levy on the alcohol industry in order to fund an independent public health body to oversee alcohol-related research, health promotion and policy advice. The levy should be set as a proportion of current expenditure on alcohol marketing, index linked in future years Measures to reduce drink driving The UK Governments should: o reduce the legal limit for the level of alcohol permitted while driving from 80mg/100ml to 50mg/100ml o introduce legislation permitting the use of random roadside testing without the need for prior suspicion of intoxication Early intervention and treatment services The UK Governments should: o ensure the detection and management of alcohol misuse is an adequately funded and resourced component of primary and secondary care to include: formal screening for alcohol misuse referral for brief interventions and specialist alcohol treatment services as appropriate o follow-up care and assessment at regular intervals ensure the provision of comprehensive training and guidance to all relevant healthcare professionals on the identification and management of alcohol misuse o increase and ring-fence funding for specialist alcohol treatment services to ensure all individuals who are identified as having severe alcohol problems or who are alcohol dependent are offered referral to specialised alcohol treatment services at the earliest possible 39 stage o implement continual assessment of the need for and provision of alcohol treatment services International cooperation on alcohol control The UK Governments should: o strongly support the European Union (EU), World Health Organisation (WHO) and World Health Assembly initiatives and policies aimed at reducing alcohol-related harm o lobby for, and support the WHO in developing and implementing a legally binding international treaty on alcohol control in the form of a Framework Convention on Alcohol Control Section 3.29 – 3.37 Living well Partnership The BMA believes that self-regulation and emphasis on with industry partnership with the alcohol, tobacco or food industry has at its heart a fundamental conflict of interest that does not adequately address individual and public health. These industries have a vested interest in the development of regulatory controls. It is essential that Government moves away from partnership with industry and looks at effective Climate alternatives to self-regulation that will ensure there is a change transparent policy development process. The BMA is a member of the Climate and Health Council which is an international organisation aiming to mobilise health professionals across the world to take action to limit climate change. The Council is calling on healthcare professionals to sign their pledge calling for urgent government-led international action on climate change. The BMA is also working to lobby the UK Governments and the NHS to: o act decisively and quickly to introduce effective action on climate change o develop binding and enforceable carbon footprint 40 reduction guidelines for the healthcare service o promote energy efficiency o support initiatives to promote the health co-benefits of actions aimed to mitigate climate change (eg reducing car use will equate to a reduction in greenhouse gas emissions, result in increased levels of physical activity and could also lead to a reduction in accidents through safer roads and public spaces) o regularly review the evidence on mitigation and adaptation policies and implement those that will make a difference to the UK and increase or contribute to global sustainability. 41